Although the focus of the Primitive Method blog is medieval jewellery, many ancient techniques were still used within living memory, and it’s for this reason that I contacted James Miller FIPG to request an interview. He very kindly agreed. His work spans that last 50 years, and most of it was done with traditional hand tools – a remarkable achievement considering the complexity of the work. Those of you who use the Orchid mailing list may be familiar with him already – for the rest of you, here’s a brief introduction:

In 1961, at the age of 15, James left school. Having excelled in art and metalwork, his careers officer arranged an interview at Padgett & Braham Ltd., a precious metalsmithing company based in Soho, London. He was offered an apprenticeship in their goldsmithing/insignia workshop, where he was taught by H. J. Jones. The Insignia department itself was responsible for making most of the major UK regalia, from The Order of the Garter down through most orders to CBEs. At the age of 21, James completed his indentured apprenticeship, and stayed with the company for several years, eventually rising to the position of workshop manager and head goldsmith. Later, he moved to McCabe McCarty Ltd., again rising to the position of workshop manager. In 1985, he set up his own company, James Miller Design.

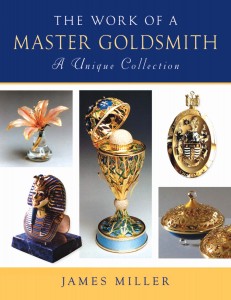

As of 2008, James is partially retired, but a book of his work has been published, titled “The Work of a Master Goldsmith; A Unique Collection”, which is available through Amazon and other booksellers. He’s now a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, a Freeman of the City of London, and a Fellow of the Institute of Professional Goldsmiths (that’s the FIPG at the end of his name).

Primitive Method: In the current education system, people expect formal accreditation very quickly. Did you expect, or receive, this?

James Miller: I was totally trade trained, there were other apprentices at the same company who were sent for day release and studied at London colleges. My master did not approve of college trained workers so I was never allowed to attend college. In my experience when I have had college trained students in my workshop, they could not cope with the time scales and pressure of delivery times to orders. I have trained two apprentices in my career, and also trained two youngsters who had started at college and wanted workshop experience. The time spent training two apprentices was a total of ten years and this process lead to me becoming called a master goldsmith in my own right.

PM: The last 50 years have seen great technological advances. Does your modern work depend on any of these advances, and are there any of the old methods that you miss?

JM: I have partially retired from work and only do occasional work for friends and old customers. I do not take advantage of any of the new technological advances, except in my photography. My work has mainly consisted of unique single items which can not be made using modern technology without major cost influences. One of my specialities is hand saw piercing, well there are computer controlled cutting machines that can mimic saw piercing, but as it takes time and money to program these machines, the costs on a single item can be prohibitive. I have experienced laser welding, but is no good for large goldsmith soldering projects. I do not use many cast products when manufacturing and when I have I have modelled the masters in wax or metals by hand myself.

JM: I have partially retired from work and only do occasional work for friends and old customers. I do not take advantage of any of the new technological advances, except in my photography. My work has mainly consisted of unique single items which can not be made using modern technology without major cost influences. One of my specialities is hand saw piercing, well there are computer controlled cutting machines that can mimic saw piercing, but as it takes time and money to program these machines, the costs on a single item can be prohibitive. I have experienced laser welding, but is no good for large goldsmith soldering projects. I do not use many cast products when manufacturing and when I have I have modelled the masters in wax or metals by hand myself.

As an apprentice I was encouraged to make many of my own tools – I made many of my mallets from beech wood chair legs. Many of my hammers were adapted standard hammers filed into different shapes. As the only apprentice in the goldsmith’s workshop, I did everything from making tea, cleaning the workshop, shaping copper pickle pans, running errands and even lighting the workshop coal fired stove in the winter mornings. For the first year of my apprenticeship I learned mostly piercing , filing and hammering. Soldering at the bench was by means of a Birmingham sidelight and a brass blowpipe, similar to the one shown in your first tool collection photo on your web page. Our forge blowpipe was a natural gas torch powered by a foot bellows. Lathe work was performed on a treadle lathe in the early days.

PM: Do you feel that you are an independant artist, or part of a network of skills and specialisations – more broadly, do you do all your own work, or outsource setting, polishing or other skills?

JM: I am a goldsmith who is part of a network of skilled artisans. I cut, shape and solder the metals into the required shapes. Small items such as jewellery I can work on as an independent artist, but on larger commissioned pieces, I use the skills of setters to do elaborate settings, a spinner to do any large spinning (small spinning I can handle myself), lapidaries, engine turners, enamellers, polishers, gold platers and casemakers.

PM: In western Europe, the small workshop has been a feature of jewellery and other metalwork since around 1000AD. Before that, the craftsmen were often itinerant, and worked with a portable toolkit. Would your traditional skills allow you to be a travelling artisan?

JM: I can make my type of work anywhere; my basic toolkit would fit into a briefcase, as long as I have a comfortable bench I can work. I remember when the country was hit by electricity cuts and our workshops continued working as all we needed was daylight and a bench, all else was using hand tools. Electricity was an extra.

PM: After the medieval and renaissance periods, the industrialisation of metalworking saw a growth in large workshops for the production of jewellery and silverware. Has this changed back recently, to smaller workshops?

JM: When I started in this trade, the company of Padgett & Braham and Wakely & Wheeler were both owned by Charles Padgett and had workshops in two buildings in Broadwick Street, Soho. There were a total of over 90 staff, goldsmiths, silversmiths, flutemakers, polishers, antique restoration silversmiths, spinners, engine turners and engravers. There were more than thirty apprentices in these workshops. Nowadays a large workshop has less than ten benchworkers. The trade changed when technology took over, and now we have to compete with low cost labour from other parts of the world. I do know of workshops that have invested in technology and speaking to the bench workers, they miss the satisfaction of creating such as they achieved in the past. Their working day now consists of assembling parts, rather than creating the parts of each item. I can see that in the future when traditional workshops become extinct there will be no craftsmen left , the workshops will be manned by machine operators, just like the printing trade.

PM: Do you think that social changes have reduced the demand of rich and powerful for high-status items? By this I don’t mean engagement rings, rather clocks, picture frames, chains of office and so on.

JM: Yes, I do think that social changes have effected the desire for such items. In the late 1960s I was involved in the making of many chains of office when many areas wanted new mayoral badges and chains, but I think current financial restraints would restrict new orders from councils. I spent a good twelve years from 1988 making goods for the Sultan of Brunei’s family and before that for the Sultan of Oman. I was lucky to have been at the height of my career when there were rich middle eastern customers stocking their collections and palaces with high value objects. I really enjoyed creating items in the style of the past Russian masters. Those times came to an abrupt end when the Iraq war started and the middle eastern customers started commissioning their goods elsewhere. Also the trade changed when the Asprey Garrard company changed hands, they stopped commissioning original pieces and moved onto designer names rather than quality. Most of my work has been sold as being manufactured by Asprey or Garrard, no credit is given to me as the maker. The only credit I got was when my pieces won prizes or awards at the annual Goldsmiths Company’s Arts Council competition.

JM: Yes, I do think that social changes have effected the desire for such items. In the late 1960s I was involved in the making of many chains of office when many areas wanted new mayoral badges and chains, but I think current financial restraints would restrict new orders from councils. I spent a good twelve years from 1988 making goods for the Sultan of Brunei’s family and before that for the Sultan of Oman. I was lucky to have been at the height of my career when there were rich middle eastern customers stocking their collections and palaces with high value objects. I really enjoyed creating items in the style of the past Russian masters. Those times came to an abrupt end when the Iraq war started and the middle eastern customers started commissioning their goods elsewhere. Also the trade changed when the Asprey Garrard company changed hands, they stopped commissioning original pieces and moved onto designer names rather than quality. Most of my work has been sold as being manufactured by Asprey or Garrard, no credit is given to me as the maker. The only credit I got was when my pieces won prizes or awards at the annual Goldsmiths Company’s Arts Council competition.

PM: For most of history, styles of art and design have been quite elaborate. Since the 80’s, these sorts of designs have fallen out of favour, to be replaced by simple forms (eg. popular engagement rings tend to be a plain knife-edge shank with a collet-set diamond). Do you think that the loss of skills in the industry is due to this simplification of form, or that the simplification is a result of the loss of skills?

JM: I think designs have changed to suit their manufacture by modern technology. I like the fact that I can make unique items that machines cannot replicate. I think that skills will be lost due to financial restraints. I could not afford to employ an apprentice in the past twenty years, mainly because of wage rates. My apprenticeship wage started at £4 per week in 1961 and only went up a small amount each year and I was being paid £9 per week in my last year. On finishing my apprenticeship I was paid the standard rate of £11 per week. I believe that today’s buyers would rather buy an antique item rather than commissioning a similar item from a craftsman. Also, I do not like the current love affair with the designer label, where quality depends on the name tag.

PM: Many British retailers now buy exclusively from countries like China, including the jewellery industry. Mass production is clearly a big factor in the simplifaction of designs. Do you think that technology can liberate us from this? Can the use of high-tech equipment like CAD/CAM allow the small workshop to become a “micro-factory”, capable of competing with mass production, or does such equipment take us farther and farther away from the skills required to produce an item by hand?

JM: I am glad that my career is coming to an end. I think this country is becoming too reliant on imports. I have seen the closures of many traditional workshops in my time. Both of my previous employers, Padgett & Braham / Wakely & Wheeler and McCabe McCarty have all ceased trading in recent years. I have never really worked on mass production items, the largest amounts of single items that I have ever made were badges and regalia in my early years. In the past 30+ years I have mainly made unique single commissioned items many of my own design. The reason that many British Retailers buy from China and the far East is that they pay their workers low wages; metal and stone prices are similar world wide. I have a friend who buys his jewellery items from a maker in Thailand who makes jewellery for a total price that equates to the prices that the materials would cost here in the UK. Who can compete with that?

UPDATE: This article has been reprinted by the Benchpeg newsletter in their September 26th 2010 issue. You can sign up to receive the newsletter at http://benchpeg.com.

{ 5 comments }

Jamie,

Thank you for interviewing James Miller. Masters like this fully deserve this type of recognition.

Jamie King

Thank Mr. Miller, for taking the time to chat with us! I’m a huge admirer of your work. I try to follow in your steps of making all my components, even my earring wires. You are an amazing artist. Thank You. Sandra B

There are still some jewellers who will try to keep the craft alive but they are getting fewer and fewer. I show students James book so that they can see what can be done using traditional fabrication without CAD/CAM and casting etc.

hi jim. i was apprentice at broadwick st, W&W . James pearl Leggat etc. I worked with jerry Doyle for a few years, i remember you and many others. i started in 1968. great times and never forgotten. had my own workshop since 1976, now have retail and workshop in Eltham south london. would love to catch up. regards Chris.

Hello Chris, Yes of course I remember you, I have a photo with you and the crew. I have not seen Jerry for about 25 years, and yes it would be great to catch up. I seem to remember that you bought a twin hull speedboat from me back in the 1970s.

My email is JMDesignFIPG@aol.com and I would love to hear from you.

Cheers Jim

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }