The Jewelry of Connie Verrusio

Fascinated by the way things work, Connie Verrusio creates radical new jewelry forms from leftover functions. Connie Verrusio has double vision: when she looks at screws, she sees earrings, and when she looks at a ruler, she sees a bracelet. For a dozen years Verrusio has found the jewels for her work in flea market junk boxes and hardware bins. Radio tubes, fishing weights and tail lights are the appropriated materials Verrusio transforms into ornaments that challenge preconceptions about what makes interesting jewelry.

9 Minute Read

Fascinated by the way things work, Connie Verrusio creates radical new jewelry forms from leftover functions.

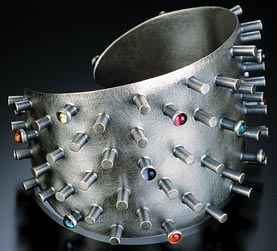

| Cuff bracelet fabricated in sterling silver with a filed texture and stones. 2″ x 6″. Photo: Robert Diamante. |

Connie Verrusio has double vision: when she looks at screws, she sees earrings, and when she looks at a ruler, she sees a bracelet. Verrusio also has a quality that the Scottish refer to as "a brass neck" - for the less Gaelic among us, that translates to pure cheek. For a dozen years Verrusio has found the jewels for her work in flea market junk boxes and hardware bins. Radio tubes, fishing weights and tail lights are the appropriated materials Verrusio transforms into ornaments that challenge preconceptions about what makes interesting jewelry.

It's not just cheeky to mix precious metal and hardware, it's also risky jewelry business. Verrusio, however, speaks hardware, the language she uses to express her reverence for the beauty of those hardworking gears and washers that lie below the surface of most things mechanical.

When Verrusio picks through a seeming abundance of supplies, she's searching for obsolete printers' type, old photos, or lock parts that are often all that remain of extinct technologies. Before they can adorn earlobes and wrists, they must be recontextualized into contemporary settings. Verrusio frames and rivets, pierces and solders until screws glow and gears sparkle as finished jewelry - whose value can't be measured in karats and brilliance, but rather lies in qualities close to Verrusio's heart.

| Commutator necklace: sterling silver, cross section of commutator (alternates current in a motor); fabricated; 1″ x 1″ x 1/2″. |

Verrusio brings to light a beauty trapped in the darkness within motors, old radios, and clock workings. These antique fragments of a hundred stories and countless fingerings not only ennoble her jewelry with their history but have a cautionary tale to tell. Even a once noble art can become extinct, unless of course Verrusio finds the hardware first and turns it into jewelry, exposing it to a new audience.

"I watch the world around me closely, always open to inspiration. Units of measure, time, and all things mechanical fascinate me. One reason I love my materials is their obsolescence in this electronic age. Film, mechanical clocks, photographs, even locks are all going the way of the record album. Sometimes my pieces are referential. They hint at the familiar, elevating the ordinary to the talisman of a modern era," says Verrusio.

When Verrusio first picked up hardware to make jewelry, she was continuing a dialogue initiated almost a century before by Marcel Duchamp. In 1915, Duchamp visited a New York hardware store, purchased a snow shovel, entitled it In advance of the broken arm, and launched the concept of Readymade art and the Dadaist art movement.

| Antique watch dial bracelet, cast and fabricated. 3/4″ x 7″. Photo: Ralph Gabriner. |

New York Story

But Verrusio's jewelry wasn't always about hardware. Her jewelry career began in the summer of 1988, when she packed a suitcase full of wire jewelry and took a bus into New York City. En route to Greenwich Village, she discovered a market set up in a parking lot on Broadway and Fourth Street. Verrusio spread a blanket on the ground and began selling her Calderesque figurative wirework - hand over fist.

To her surprise, the fish bowl necklace with the swinging fish and the anatomically correct man and woman earrings were top sellers that earned her enough money to rent a table the following weekend. By the end of the month she had sold enough jewelry to support her 20-year-old self New York style, which meant cohabiting with three roommates in a two-bedroom apartment.

Playing with wire had always felt right for Verrusio, but watching her creations fly off the table confirmed that bending wire was more fun than writing papers. She finished her degree at the University of Rochester in1989, then moved permanently to New York and its ready market for her jewelry.

Up until then, Verrusio had used only pliers and instinct to create her wirework, but she was now ready to learn silversmithing. And as if on cue, along came two jewelry-altering experiences.

"I met a friend from 6th grade and lo and behold we were both jewelers and she had all the jewelry-making equipment. She showed me how to use the tools and, whenever I took care of her cats, I'd tinker in her studio and melt things. It felt so comfortable; I never had trouble experimenting or figuring things out. I always had a natural sense of how to make things. I began buying tools: a flex shaft, saw, ball peen hammer, and a vice. All my early jewelry had been cold connected - I used lots of riveting - but buying a torch changed that."

| Electric lug pin: copper and brass terminal lugs (from old radios); fabricated and oxidized; 2-1/2″ x 2″. |

And, as every jeweler knows, soldering begets a polishing machine and belt sander, and those demand a studio. Verrusio found a live/work space in a former factory in Brooklyn and, because she was no longer making jewelry on her bed she could fire up the torch and alter metal. When she wasn't working, she was walking, and during a walkabout in Chinatown, Verrusio found her Mecca, known to New York artists and jewelers as Canal Surplus.

"That store inspired me and appeared at just the right time when I wanted to start adding non-traditional components to my jewelry. Here were thousands of small parts, many in brass, which I love. I love the deep yellow color it turns when it mellows with age and the way it solders so beautifully with silver. Standing in the store, I could feel my ideas blossoming on the spot." That day, standing in Canal Surplus, Verrusio knew that henceforth her inspiration would be as plentiful as the bins of hardware surrounding her.

| Necklace fabricated from sterling silver and brass gears with garnets; 1″ x 16″. Photo: Ralph Gabriner. |

Shifting Gears

A simple brass gear was the first machine part to steal her heart. It resembled the sun, was the color of sunshine, yet was a reminder of the passage of time. Its beauty seemed inexhaustible as she worked it into a new line of jewelry.

"Then I had the idea of cutting the heads off screws to make earrings. These have become my bread-and-butter and eventually I cast the brass screws in sterling."

Although Verrusio sold her jewelry at the market every weekend, she never tired of watching her customers' delight when they encountered the unexpected. The delicate flower petals on a Verrusio brooch were layered radio lugs, while a copper pendant with a high-toned abstract pattern was a sliced commutator that once alternated currents. Men especially liked fingering the screw cufflinks, keyhole tie tacks, dice cufflinks and extension ruler bracelet.

One day a friend gave her the 16mm film he discovered when he pulled down a ceiling during a construction job in Westchester. It didn't take long for Verrusio to see the 1940 black and white images as earrings, pendants, and bracelets. Thus began the predawn Sunday morning ritual of flea markets and antique fairs, on the hunt for materials. Verrusio poked through junk boxes for time-patinated machine parts and bargained hard for old photos that had miraculously survived countless owners. One Sunday, foraging for lock parts, she uncovered a box of dusty treasures.

| ning gear earrings: sterling silver and pocketwatch gears; fabricated; 1″ x 2″ x 1/2 " |

"I already knew how wonderful the grays and blacks of old photos look with silver. They were as beautiful as any gemstone. But tintypes are special. Tintypes fall between daguerreotypes, which were photos printed on silver, ambrotypes, which were printed on glass, and modern photos. [They were] produced by the millions in the US because they were relatively inexpensive; even poor people from 1860 to 1890 could have their photos taken - although they sometimes had to borrow ill-fitting dress clothes from the photographer. People approached being photographed with great seriousness and formality, dressed in their best clothes. I often find myself lost for minutes on end gazing into these photos. In particular I love the eyes or the grace of a woman's hand on her husband's shoulder. I imagine their lives or marvel at the intricacy of a dress."

As well as being somewhat plentiful, tintypes were protected by a hardened, century-old emulsion, making them sturdy enough to withstand riveting on silver. Another jewel was added to Verrusio's collection.

After years of living in New York and working outdoors, Verrusio was finding the constant worries about the weather and rent a grind. She had noticed too that vendors selling imported goods and commercial T-shirts were replacing the young designers, who had moved to SoHo. Verrusio constructed a portable display and joined this lively community of artists and craftspeople selling their wares on SoHo's streets.

"This didn't last long because the mayor at the time, Dinkins, decided to crack down on this illegal activity by sending undercover police out to arrest the vendors. Sure enough, one hot July day I was arrested, handcuffed and hauled off to jail. I was released with a slap on the wrist, but this proved to be the jump-start I needed to get my slides together and apply to the American Craft Council's wholesale craft show."

Verrusio now stocks 25 galleries, including the National Archives in Washington, DC, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the International Center for Photography in NYC.

Verrusio is one of those lucky people who has always made her living doing what she loves. Selling everything she ever made has encouraged experimentation that recently produced a pencil and magnet reproduced in silver.

| Magnet brooch: sterling silver and paint; fabricated hollowform; 1/2″ x 2″ x 3″. |

"Many of my customers find my work humorous. They take great delight in recognizing the objects and often laugh out loud at the silver nail bracelet, the inch pin, the screws, and keyhole earrings. I suppose they also enjoy my irreverence for the 'preciousness' of jewelry."

A few years ago Verrusio suffered New York burnout and moved from the Big Apple to Apple Country. Here, north of the city, there's room for hardware and farm-ware to spread out comfortably alongside embroidery and all things brass, which, tumbled together, made up the growing collections of a confessed packrat.

"I've given up my urban life and live in the Hudson Valley with my cats, Tiny and Hank, and my dog, Boo. It's a beautiful rural area at the base of the Catskills Mountains with lots of rivers, rocks, and apple orchards. I left NYC because I grew tired of the garbage everywhere, the anonymous hustle and bustle, and working so hard to pay the high rent. I longed for a garden and my own home, so I found an old farmhouse with 13 acres and happily left the city behind. I love the quiet here and my summers are taken up with my ever growing vegetable garden. I'm a serious gardener now! I've recently discovered the joys of growing hard-shell gourds with their incredible variety of sculptural forms. I also love woodworking and this summer I built myself an outdoor cedar shower that I'm really proud of. I may also begin making furniture and lamps someday, when studio space permits."

Verrusio's new studio on her sun porch has views of an apple orchard, mountains, and woods. It's likely that this new imagery will creep into her jewelry, replacing the mechanical world with a natural one. For now, she continues to create jewelry that pays homage to the trades and those small, unseen, underappreciated wonders that keep our watches ticking, VCRs taping, engines revving and workaday lives running smoothly.

And yes, there is a surplus store nearby.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.