1984 Jewelry International Exhibition

26 Minute Read

With the exception of "New Departures in Jewellery," held at the American Craft Museum last summer as part of the "Britain Salutes New York" festival, it has been well over 10 years since the ACM offered a full-scale show of new work in jewelry. So their ambitious, concurrent staging of "Jewelry U.S.A." and "Jewelry International: Contemporary Trends,"—in itself, the first international exhibition of contemporary jewelry to appear in the United States-constituted a major event.

As installed at the American Craft Museum II, in the rear, glass-walled lobby of the International Paper Plaza, the cases housing American jewelry blurred into those of "Jewelry International." And, to a certain extent, it seems the museum may have intended the two shows to be taken as a whole—as testimony to new levels of sophistication in jewelry making. Vincent Beggs, the new educational coordinator for the museum, commented, for example, that the AUM's chief aim, here, was to raise the consciousness of viewers unfamiliar with contemporary jewelry and to encourage them to look at the individual pieces of jewelry as carefully as they would look at any painting or sculpture. On one level, at least, this goal seems to have been achieved. Judging from random comments overheard on numerous visits, most visitors did take the two shows as one and were very impressed with the variety and virtuosity of the jewelry presented. If they did not necessarily equate this jewelry with painting or sculpture, it is probably safe to say that, for many viewers, the combined exhibitions did stretch their perception of what jewelry can be and do.

But for those already familiar with contemporary jewelry, the simultaneous installation of "Jewelry USA" and "Jewelry International" offered the opportunity for a more serious and critical assessment. Taken as a type of comparative exercise, and not as a homogeneous presentation, the concurrent exhibitions provoked questions of national identity-were there distinctly American characteristics that emerged from "Jewelry USA?" for example—and of the identity and meaning to be found in jewelry-as-art.

From inception on, the two shows differed significantly. Culled, as it was, from a national competition—juried by jewelers Sharon Church and John Paul Miller and gallery owner Helen Drutt—"Jewelry USA" aimed above all to "survey the range and diversity of artists at work in the discipline at the current time." According to competition coordinator Richard Mawdsley and Society of North American Goldsmiths Presidcnt Arline Fisch. "Entries were encouraged from jewelers producing one-of-a-kind pieces, from those involved with studio production, and from all those experimenting with new directions and attitudes."

"Jewelry International," on the other hand, represents the curatorial selection-by-invitation of Drutt alone. This means that while "Jeweler USA's" jurors were limited to the best examples of the variety of trends that have characterized American jewelry in the last decade, Drutt was free to solicit only those jewelers whose work she found inspirational. It is a difference that frustrates any real comparisons and ultimately does a disservice to the Americans. Drutt's international survey comprises a selection based on the clearly articulated—if somewhat eclectic and personal—values of a long-term supporter of serious craft-as-art. In her carefully written catalog essay, Drutt underscores her strong commitment to an historic evaluation and analysis of jewelry and speaks to her preoccupation with influences and sources.

More important, Drutt focuses on individuals ". . . who are committed to a concept of body ornament that does not compromise the integrity of the individual artistic idea." However briefly she describes the contributions of the jewelers in her survey, Drutt names names; her effort to identify the genesis of specific ideas and formal innovations not only allows her to give individual jewelers credit, it is an essential step in allowing jewelry to be treated as art and not as "anonymously" created craft. One might quibble with some of Drutt's selections, but, overall, "Jewelry International" offers strong evidence that thinking craft-artists are challenging the limitations and expanding the possibilities available to traditional jewelry.

No such sense of focus or underlying conviction emanates from "Jewelry USA." There were some wonderful, poignant, even powerful pieces and an outstandingly high level of technical facility throughout the exhibition, but virtually nothing that could be called radical. It was difficult to discern just what criteria were brought to bear by the jurors in the winnowing of some 2,200 slide submissions down to the 220 pieces actually displayed. The excerpted dialogue of the jurying process offers more insight into the jurors' concerns than can be found in their brief one-paragraph introduction to the catalog. But these jurors seem more interested in observing general trends—for example, the "pervasive use of color" or the fact that, for the most part, this work "signals a distinct return to jewelry that is ultimately wearable"—than in calling attention to the specific contributions of individual jewelers.

As a result the jurors' additional claim—that "this collection of handmade jewelry focuses on concept. . ."—seems less convincing. In fact, one was left with the overriding impression of an abundance of virtuosity and a relative paucity of clearly discernible conceptual concerns—much the same impression one receives walking through the Northeast. Craft Fair these days (not coincidentally, another juried show). Whether this situation owes more to the museum's direction, the jurors involved, ,juried shows in general, the jewelers, themselves, or—as Robert Lee Morris suggested in Summer. 1984 issue of Metalsmith—to the academic institutions in which most American jewelers now train, a nagging question raised by "Jewelry USA" is "What makes American jewelry so benign?"

Rose Slivka offers a harsh, but insightful, response to this question in her review of last year's "New Departures in Jewellery." Her complaint centered on the notion of the American jeweler as "piranha"; the disarming, but all too prevalent tendency for American jewelers to appropriate and decontextualize stylistic or esthetic effects, while disregarding the sources that inspired them. For Slivka, the London-based jewelers were ". . . the most exciting phenomenon that has come our way in the last twenty years…. They have undertaken to pose the serious questions of our time—individual responsibility, social mores, status true and false, daring to tread the risky bridge between art and design, philosophy and politics and in so doing they project . . . an affirming spirit of courage and thought." Whereas: "In this country where revolution is considered an American tradition, the jewelers have played a conservative role. American jewelry is the most staid, the most concerned with 'clientele.' True, they have made technical and material innovations, particularly as 'sculpture to wear' in which they would appear to put formal values over gold and precious stones. Nevertheless. the largest part of the output has been the general run of 'chachkas' with technical and stylistic refinements and no ideas."

None of the "Jewelry USA", jurors show evidence of concern over the "cultural cannibalism," dearth of ideas. or dependence on "clientele"' that Slivka addresses in her critique of American jewelry. In fact, where Slivka criticizes Americans for their over-responsiveness to "clientele," the jurors praise return to an interest in wearable jewelry as a retreat from the esoteric and ambiguous objects that characterized much American jewelry art a decade ago. And, while all three jurors, when asked to comment on "the criteria applied to their evaluation of entries," stated their desire for some sort of unique quality in the work, only Drutt even alluded to the role that a "point of view" might have in contributing to that unique quality. Where Church ". . . wanted to be instructed as to an individual's unique approach," and Miller sought ". . . some sort of feeling or presence. . ." in the piece as opposed to the maker, Drutt reiterated her search for an "excellence" that goes beyond technical expertise to ". . . a sense of originality in the work which permits me to identify with the maker . . . (and) . . . a point of view that allows me to know that the human spirit is continued . . ." (All emphases are my own.)

Both Slivka's concern with the "reactive" tendencies motivating many contemporary American jewelers and Drutt's focus on the relationship between the originality of a piece and the point of view of its maker were pointed out by Wayne Higby, two years ago, as problems facing all those Americans attempting "craft-as-art." In his review of the ACM's "Young Americans: Award Winners," Higby described craft as, fundamentally. "a celebration of skill and the beauty of materials," while ". . . art is a revealing of the unknown." After evaluating the work of the young Americans "award winners." Higby suggested that, for the craftsman, achieving significant art entails making a choice: "The choice is to explore the boundaries of our fine-arts heritage or to find in crafts new dimensions of artistic achievement. . . . Choosing between these alternatives presents a challenge to those artists who possess the traditional craftsman's gifts. Unfortunately, the trend has been to avoid making a choice. Ideas are lost in efforts to achieve recognition, and true artistic vision is continually blurred by a willingness to alter beliefs to fit the moment. As a result, clarity in craft remains elusive."

The problem of identifying and communicating vital ideas is not, of course, unique to American craft. One of the most tired stereotypes of Americans, in general, centers on our anti-intellectual impatience with ideas and our obsession with materials and image. At the same time, a good deal of the most recent, Post Modern criticism has grown out of a belief that there can be no more "original" ideas. Yet such Post Modern notions as "appropriation" or "pastiche"—what professor of literature Frederic Jameson has described as the mimicry of the "mannerisms and stylistic twitches" of a celebrated style, without the sense of humor and irony found in true parody—or even the so-called "death of the subject" are not precisely relevant to contemporary American jewelry. The "cultural cannibalism" that distresses Slivka and the problems raised by Higby refer to slightly different phenomena, if only because of the relative youth of the American craft-as-art movement. Such recent trends in American jewelry, for example, as the widespread use of Japanese materials and techniques, the juxtaposition of conspicuously disparate materials, or even the proliferation of "speculum" several years back, or of titanium and niobium more recently, have little to do with the self-conscious debunking of Modernist canons. Rather, they speak to the far less ideological but consuming appetite that many contemporary American jewelers seem to have for novel esthetic effects—an attitude that is decidedly stimulated by an increasing American market for "art" jewelry and that may also be encouraged by our academic jewelry departments.

The transition from student to mature, independent artist and the identity of the craft artist vis-à-vis popular culture. As all of the "Jewelry USA" jurors acknowledged, jewelry-making has become increasingly viable as a profession in this country, with more and more American jewelers professionally trained and economically self-sufficient—which is, of course, a good thing. But to maintain this self-sufficiency, most of these jewelers must produce two, theoretically different, types of work. As a result, the tremendous surge in options for American crafts and craftsmen can also encourage innovation at the expense of meaning—or a failure to distinguish between the responsibilities of artist and artisan, between conceptual purpose and esthetic presence.

It is possible, too, of course, that many American jewelers may not be interested in "conceptual purpose," may intentionally work to create elegant or enjoyable decoration and to ignore the deeper meanings available to jewelry—be they spiritual, metaphysical or political. My own impression, however, is that the American culture offers less precedent for "meaningful" jewelry. Unlike many of the cultures represented in "Jewelry International"—certainly the European countries and Japan—the United States can claim little in the way of a deeply rooted, commonly understood tradition of goldsmithing against which contemporary American jewelers might establish some new identity. We have no dominant church, none of the rituals esthetics of the Japanese, not even the polemical underpinnings that motivated William Morris's revival of the British Arts and Crafts Movement and, later, de Stijl and early Bauhaus. So, whereas much of the impetus behind current jewelry making outside the United States grows out of a profound, if adversarial, reaction to an entrenched tradition, or traditions, American Jewelers, by and large, have to look elsewhere for inspiration. While international exhibitions, workshops conducted by prominent non-American goldsmiths visiting the United States and the proliferation of media featuring jewelry and goldsmithing have catalyzed a great deal of cross-cultural exchange, one of the most striking contrasts that emerged from the juxtaposition of "Jewelry USA" and "Jewelry International" was the lurking presence of a strong sense of history behind most of the international work and the conspicuous absence of it in the American work. This contrast may also explain the greater irony and polemic edge underlying much of the work in "Jewelry International."

Compare, for example, the Dutch goldsmith Paul Derrez's pleated plastic and steel necklace (JI #34) with Arline Fisch's red coated-copper, machine-knitted collar and cuff (#40). When Drutt observes, in her catalog essay, that Derrez's "pleated plastic collars remind us that Rembrandt's guildmasters' collars are not so far away in time," it is safe to say that she is calling attention to an immediate, if superficial, association no lost Derrez's Dutch audience. This simple reference gives Derrez's necklace an historical dimension by calling on (collective) memory for some of its meaning. But Derrez also plays on the irony of this association by substituting the industrial, nonvaluable materials of plastic and steel for the fancy lace that endowed those old Dutch collars with the status their Bourgeois wearers desired. And then Derrez invests this plastic and steel with an even greater sense of duration transforming the simple circle into a Moebius-strip, creating a mathematical analogue for a time-space continuum, that, not insignificantly, also lies gracefully around the neck.

Fisch's boisterous, more whimsical collar and cuff conjure no such ironic or multivalent associations. Conspicuously free of historical or symbolic significance, they celebrate, instead, the liberation from more modest, conservative jewelry and the time-saving technical innovation of machine-weaving. The form, itself—less controlled and responsive to the body—is determined, to a great extent, by the machine-weaving process. And the color, while exuberant, seems somewhat arbitrary. Yet one feels that these considerations are not as important to Fisch. She seems far more interested in providing an immediate sense of delight and bemused pleasure, associating facility with felicity.

John Paul Miller's, I think accurate, observation that most of the work in "Jewelry USA" had ". . . a feeling of being made for the present. . . a transient feeling. . . ." would seem to speak to this difference in intention. His own pieces (e.g., #124), while never much to my own taste, certainly reinforce his belief that jewelry should be made to endure over time. The painstaking granulation and cloisonné, even the conspicuous use of gold—John Paul Miller signatures—all reinforce this belief. But Miller's feeling that contemporary American jewelry is characterized by a spirit of experimentation seems corroborated by much of the work in "Jewelry USA."

Over the last two decades, American jewelry has moved away from the dominant influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement, from an idea of "hand-craftedness" manifested in irregularities of surface, undisguised tool marks, an uncompromising truth to materials and relatively straightforward tehcniques. Caroline Strieb's Gardens of Mars (#178) was virtually the only example of this earlier "tradition" of American handmade jewelry in "Jewelry USA." With its richly reticulated, rough-hewn silver beads, careful balance and palpable sense of weight. Strieb's necklace had an honest, direct presence that seemed almost old-fashioned, thought welcome, amidst all the "high-tech" jewelry surrounding it. The clarity in her work in no way implies a lack of sophistication or control. But it represents a type of obviously hand-crafted, anticommercial jewelry that, for the most part, has been replaced by a notion of handmade jewelry based on technical refinement and innovation. American jewelry has become more varied and the lines between commercially produced and handmade jewelry have narrowed considerably.

The "pervasive" use of color, broader range of materials employed, and rise in wearable objects observed by the "Jewelry USA" jurors attests to these characteristics—which also reflect the pluralism evident in the larger American art and fashion worlds. The prevalence of color, in particular, may parallel the proliferation of "Neo-expressionist" painting here and in Europe in the last few years. But the presence of color alone does not guarantee and "expressive" piece of jewelry. The rainbow hues of "interference" coloring on titanium, niobium, tantalum, etc. have become ubiquitous in both commercial and handmade jewelry. (I counted no less than 14 pieces that made use of it in "Jewelry USA.") This "ups the ante" on its expressive potential and, unfortunately, works to undermine such pieces as Dean Smith's stick pins (#174 and 175), Tamiko Kawata Ferguson's Feather Necklace (#38), Victoria Howe's necklace (#83) or Doug Samore's neckpieve, N1 4 (#149). In several of these the selection and application of the color bears no compelling relation to the form. Ferguson's Feathers Necklace and Joke Van Ommen's Kite Pin #1 (#195), on the other hand, use the gradual transition of hues to reinforce the idea of the object (feather) or sensation (a kite flying) suggested by the title and form of the piece. Ommen's pin is more effective for its discretion, limited palette and acknowledgement of the superficial—in the literal sense of that word: on the surface, only—nature of interference coloring.

Other methods of coloring stand out, by comparison. Linda MacNeil and Sara Young use the rich, pure color of glass effectively. MacNeil's saturated primaries and secondaries provide a rich counterpoint to the tightly controlled, symmetrical arrangement of her balck-and-white triangles and cylinder beads, while Young exploits the capacity glass has to sheath saturated colors with more transparent layers in a necklace whose flexibility belies the fragility of the individual glass beads. (MacNeil #115; Young #206). And now that the deluge of mokumé and married metals has subsided, somewhat, Gayle Saunders's persistent experiments with juxtapositions of colored and patterned metal surfaces begin to stand out—for their subtlety and because Saunders no longer allows the surface begin to stand out—for their subtlety and because Saunders no longer allows the surface effects to dominate her jewelry. Her two brooches and necklace (#152, 153, 154) were some of the most satisfying pieces in "Jewelry USA."

In brooch (#152), Saunders frames a paper-thin, ragged patch of moired, pastel golds, centering it withing a much larger circle of black, mild steel. With the patch itself framing an empty, square hole, the pin works to "feature" the clothing onto which it gets pinned. In addition, Saunders plays on the opposing material properties, as well as the color, of the two very different materials. By forming the thin, steel wire into a perfect, smooth circle, she undercuts its inherent tension; the precious bit of supposedly ductile gold, on the other hand, is little more than a rough, torn fragment. Yet by "mounting" the fragment, dead center, within the circle, Saunders acknowledges its lingering preciousness. On a dark garment, the black circle would all but disappear, thrusting the gold into stark relief.

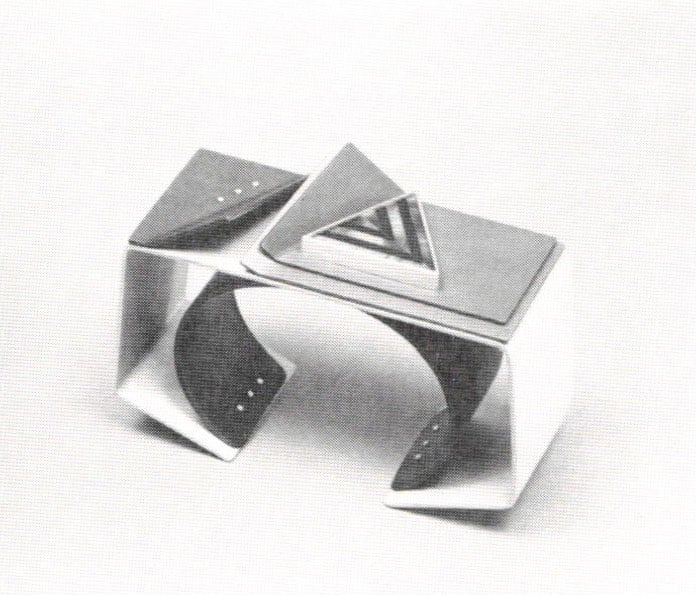

Another jeweler who worked magic with color and sensuous form was Sachiko Uozumi. A Japanese-American who has only been making jewelry for several years, Uozumi has said that living in the United States has actually sharpened her understanding and appreciation of Japanese craft and esthetics. Her two bracelets and necklace/belt, titled The Crystal Cube is a Timeless Box for Pandora (#194), reveal the austere, controlled and reductive beauty we associate with a Japanese esthetic, yet they incorporate no traditional Japanese materials or techniques—no mokumé, no shibuichi, no shakudo. Instead, Uozumi achieves this (Japanese) intensity by orchestrating a series of highly calculated oppositions. In the bracelets, the hard-edged, architectural planes of the lucite are made to curve sinuously, conjuring an absent arm. And in both pieces, rich gold-colored, metal-leaf transforms the slick, industrial lucite and air-brush colors into enigmatic prisms, rendering the "crystal cubes" indeed, "timeless."

Uozumi heightens this enigmatic pitch even further in the necklace/belt by connecting the individual cubes with thin, dark leather knots, actually quite flexible, but appearing, for all the world, to be bits of sharp, barbed wire. Her materials become "mediums" in the mystical sense, operating simultaneously on a metaphysical ad kinesthetic level. Yet ironically, the sensuous quality in Uozumi's jewelry—its responsiveness to the curvature or movement of the body—owes more to ideas gleaned from contemporary, body-conscious, American fashion than to traditional Japanese esthetics. Ironically, because with all the discussion about a "return to wearability" in contemporary American jewelry, only a very few of the pieces in "Jewelry USA" respond so profoundly to the body. With several exceptions—notably Mary Lee Hu's exquisitely simple and elegant Choker #67 (#86) or Robin Quigley's marvelous fringed, almost fetishistic, pairings of bracelet and earrings (#135, 136, 137)— "wearability" amounts to little more than a reduction in scale or the appendage of wearable findings to otherwise autonomous objects.

While the tide of large-scale, self-consciously artsy, exhibition objects has certainly ebbed a bit, far too many of the jewelers represented in "Jewelry USA" seem to be "problem solving"—continuing along lines established by academic exercises. Occasionally, a rigorous use of this "academic" process of experimentation encourages a refinement of form-idea relationships. Both Rebekah Laskin and Don Friedlich, for example, gain from their use of the brooch/object format as a "constant" or "control" for a series of in-depth, focused investigations of material phenomena or abstract ideas. Laskin's brooding and darkly beautiful enamels, with their narrow range of neutral colors, take on the intensity of their maker's nuanced inquiries into color density, light and shadow. Don Friedlich's less consistently successful efforts, nevertheless, reveal a sophisticated sensibility and a thoughtful exploration of the essential properties of materials and the dynamics of controlled forms. His Balance Series brooch (#50) is a striking essay in architectonic balances and surface tensions. Susan Hamlet uses the bracelet format in similar fashion, analyzing functional processes and categories of materials. In Shim Bracelet #3 (#70), Hamlet "displays" her "findings" by casing them within plastic tubing—ironically transforming wearability into exhibition.

But more often, the "problem-solving" encouraged in university jewelry departments results in technical showpieces, such as Daniel Jocz's elaborately hinged and inlaid bracelet Taper (#91). Flexibility here would seem to be the "subject" of the bracelet which impresses more for the obvious work it required than for its grace or genuine wearability. Edgar Morey's Roller Ring Five, One, and Six (#126) and Christopher Secor and Leslie Leupp's bracelets (#161 and #103, respectively) reveal equally self-conscious efforts to accommodate real fingers and wrists, but somehow come off more elegantly. At the same time, while Miller's remark that "There weren't many pieces in ("Jewelry USA") that took advantage of movement. . ." is, again, quite astute, earrings for pierced ears—as Miller also noted—provide some refreshing exceptions. Faith Allotey-Jordan's ear-framing Lunar Ellipse(s) (#6) and Philip Fike's broomlike bunchings of delicate, forged yellow and white gold wires (#39), for example, really do move in response to the body. Sandra Enterline's earrings (#37) of three diminishing circles, lashed with flat copper wire and Pam Levine's pair—in which a delicate taper of shiny silver dangles from a seemingly bulky roll of flat, black chrome—make use of the free space beneath the earlobes to play on the perceptual discrepancies between visual heaviness and actual weight.

Pieces as varied as Frank Trozzo's Masque Ring #1 (#192), Ignatius Widiapradja's Bamboo Pins #2, #4 and #5 (#202), Pamela Whynotts's Dead Fish (#200) and Stephen J. Albair's Kiss (#5)—to name only a few examples—all remain essentially self-referential, static objects. I found Albair's Kiss particularly troubling in its effort to elevate a humble but attractive pin into an "art-object" by means of an elaborate, oppressive, grossly overscaled farm. I also had difficulty with several objects of obscure purpose that, 10 years ago, might have hung on the wall, but have been shifted into the 47th Street category of "conversation piece" jewelry. Fisch cites the presence of such items as hats and the increase in rings, bracelets and necklaces—as opposed to brooches—as evidence of a greater interest in "ornament." Quigley's jewelry, I think, with its primitive associations and incorporation of sound, can truly be described as "ornament," as can the work of Uozumi and Hi. In each of these cases, the jewelry gains depth and resonance through its capacity to transform a literal idea into its formal/material equivalent so that one "feels" rather than "thinks" a response to the piece. In jewelry, this almost always entails some sort of dialogue with the body.

Uozumi, not coincidentally, has become a member of Robert Lee Morris's "Art-wear" stable, and it is Morris, I think, more than any American jeweler, who should be credited with exploiting the idea of "art to wear"—not by creating art objects for the body, but by celebrating the body with art. His "signature" torso displays are less gratuitous display gimmicks than essential supports for work that is not realized without a body. It may be a bit cynical to observe that wearable jewelry is more salable, but this seems a point worth mentioning. (Similar criticisms have been leveled at the current art market: painting sells a good dead better than site-specific sculpture.) Morris has confronted the market "avant-garde" fashion. His work may be quickly appropriated by the world of high fashion and promotion, and he may not be exploring the political capacity within jewelry that Slivka observed, above, among certain British jewerlers. But Morris's clients, too, must "demonstrate commitment" to his jewelry. This is in marked contrast to, for example, Carole Bowen's Eraser Suite rings (#17) which may harbor some political intentions—as "anti-cocktail" rings, perhaps—but give little evidence of requiring rings to make their point—or pun.

If "Jewelry USA" is to be taken as representative of contemporary American jewelry, then a kind of convoluted, punnish humor ought to be cited as a truly American characteristic. This literal humor and sense of play—as opposed to the more serious irony that distinguishes so much of the European and British jewelry—shows up in some very dissimilar pieces. Tina Fung Holder's neckpiece Contessa-SGX (#82), for instance, is an unpretentious, marvelously simple veil of gold and silver safety pins suspended on an "armature" if crocheted cotton thread. And Cat Glazer's Black and White Neckpiece (#58) has the energy of a hundred live and kicking legs—a string of Rockette legs dancing. Yet Glazer's reduced, repetitive modules and stark black/white color contrast lend the neckpiece and elegance that belies its whimsical associations. Laurie Hall's humor takes a more narrative turn, deriving some of its charm from the "aged" look of her materials and the folk-art sources it seems to tap. Her titles are more than clever and in her most effective work, such as Chief Bone Gone Fish' in Bone (#68), the narrative works to carry one's eye around the wearers' torso, unifying a necklace that also functions as a collection of charms or talismans. On the other hand, Jocelyn M. Merchant's brooch Repair (#119), while controlled and intentionally literal, comes off as a precious and fleeting play on words. I had similar problems with Kate Wagle's Party Trick II (#197) brooch and Gail Marie Fisher's Party Wear Series: Brush Bracelet (#42), although in Fisher's case the joke was funnier and had a more satiric edge. When compared with, for example, English jeweler Caroline Broadhead's Veil Collar (JI #21), these American pieces seem almost gratuitous. And the persistent inclusion of such self-indulgent items as David Freeda's Cuban Molasses pin (#49) or Peter Jagoda's Spurred on to Excess (#89) simply baffles me.

The tradition of "found objects," however, retains a good deal of vitality for a number of American jewelers. With collage and assemblage so significant in 20th-century art, it is no wonder that they figure heavily as formal strategies for both Americans and Europeans. But, whereas the European use of found objects tends to derive, to a major extent, from the Church tradition of reliquary objects and a European obsession with primitivism, as Drutt pointed out in the dialogue, American jewelers owe more to the influence of Pop art—a reflection of the detritus of commercial culture—and a desire to make jewelry more personal and less precious. Three jewelers who couldn't produce more different looking jewelry—David Tisdale, Elizabeth Garrison and Debra Rapoport—all find their inspiration in found objects not usually associated with precious jewelry.

There were other pieces I particularly enjoyed. Rachelle Thiewes, who has consistently produced sensuous, superbly crafted body ornament, gives new meaning to the charm bracelet in her Series Bracelet No. 2 (#184). Jeannette Fossas's flat, subtly textured and supremely simple bracelet, by contrast, reveals the tremendous power available to pure geometric forms. Michele Bussiere's delightful neckpiece comments wryly on jewelry's capacity to project personal "signals; his UHF (#20) is less a neckpiece, really, than a body antenna. With his neckpiece Delta (#14), Jamie Bennett moves encouragingly closer to establishing some sort of dialogue between his always serious, but often self-absorbed, autobiographical enamels and the human body. And Pat Flynn's brooch (#45) gives testimony to the fact that an object can be intensely intimate, even if it retains its sense of "objectness." Flynn is exceptional in his ability to coax profound meaning from precious and discarded matter, alike. His inspired compositions establish absolute equivalences between the most unlikely materials and shapes.

As with any craft, jewelers must constantly grapple with, and struggle against, the problems of use and materials—the two phenomena fundamental to craft. But the uses of even the most traditional jewelry are inherently rich in magic, a send of duration over time and the power of personal expression. More than any other craft, jewelry has the potential to mediate the tension between public and private meaning—and between maker, object and user. Ironically, what most seems to threaten the power of contemporary American jewelry is the success so many of our jewelers have achieved. If "the market" rewards more conservative, benign work, the jewelry-artist's task is to challenge, not appease that market. And the museum's responsibility is to distance maker from market—not simply to relocate "value" from the intrinsic value of materials to the extrinsic value of handcrafted work, but to support only those craftsmen who reveal the same control over dynamic ideas as they demonstrate technically. Large, juried shows serve primarily as showcases, conferring status that parlays into profit. As it becomes more and more difficult for the artist to take an independent stance, the museum should work to counter, not encourage, the leveling effects of the commercial market.

Notes

- Arline Fisch, Richard Mawdsley, "Jewelry USA" catalog, introductory paragraph, May, 1984.

- Helend Drutt, "Jewelry International: Contemporary Trend," catalog essay, May, 1984, p. 1.

- Sharon Church, Helen Drutt, John Paul Miller, "Jewelry USA" catalog, introductory paragraph, May, 1984.

- Ibid.

- Robert Lee Morris, as quoted by Vanessa Lynn in "Robert Lee Morris" Metalsmith, Summer, 1984, p. 30.

- Rose Slivka, review: "Britain Salutes New York: New Departures in Jewellery," Craft magazine, September/October, 1983, p. 44.

- Ibid, p. 45.

- "Conversation among Selectors of 'Jewelry USA' Show," unpublished transcript of discussion between Sharon Church, Helen Drutt, and John Paul Miller, led by Arline Fisch, pp. 2 & 3.

- Wayne Higby, "Young Americans in Perspective," American Craft, April/May, 1982, p. 24.

- Frederic Jameson, "Postmodernism and Consumer Society," in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Edited by Hal Foster, Bay Press, Port Townsend, Washington, 1983, p. 113.

- John Paul Miller, "Conversation," p. 4.

- John Paul Miller, "Conversation," p. 2.

- Arline Fisch, "Conversation," p. 2.

- Helen Drutt, "Conversation," p. 6.

Note: All citations of objects in exhibition or catalog use number designated either by "Jewelry USA Catalog Listing," (#xx) or "Jewelry International Catalog Listing," (JI #xx).

Linda Norden is a PhD candidate in Art History at Columbia University and writes on art and craft.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.