1991 National Metal Competition

13 Minute Read

Cu3, as a national metal competition, was a sequel - albeit more than ten years later - to Copper 2 (1980) and to the Copper, Brass and Bronze Competition in 1977. The first two exhibitions were shown at the Museum of Art at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Cu3 was shown at the Old Pueblo Museum, also in Tucson. It was installed by the director of the museum, Diane M. Johnson, and her staff, Philip Renner, Phyllis Rapagnani and James Jenkins.

All three exhibitions were conceived to show the richness, versatility and diversity of expression possible in copper. Michael Croft, professor of art and head of the metals program at the University of Arizona, was co-director of the first two exhibitions and project director of the current exhibition. In 1977 he stated in the catalog for the first exhibition, "Competitive exhibitions, especially those emphasizing metalwork, have for the most part rewarded the precious metals of silver and gold, overlooking what I feel is the most creative and imaginative work being done. It was the desire to see an exhibition spotlighting the rewarding expression in the materials of copper and copper derivatives that led to my proposing this exhibition."

When I was told of his plans for Cu3 after such a long hiatus, I asked why. Has the field changed that much? Is such a show really needed? What are your expectations for the exhibition? My questions couldn't really be answered until the show was mounted, and so I agreed to help in any way I could. My current professional activities didn't allow extensive involvement in the planning and implementation of the exhibition, but I did agree to serve as one of the jurors of the exhibition. Eleanor Moty, professor of art at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, internationally known for her work in photo etching, and David Pimentel, professor of art at Arizona State University at Tempe, known for his large-scale vessel works in copper, were the other jurors.

Unfortunately, the jurying was done from slides, as was the case for the two previous copper exhibitions. There were 1,200 submissions to Cu3 (162 pieces and 77 artists were shown), as compared to 1300 submissions to Copper 2 (233 pieces and 176 artists were shown) and 1200 to the first exhibition (236 works and 157 artists shown) in 1977. Clearly Cu3 was the smallest of the three exhibitions, both in the number of pieces shown and the number of artists represented. I can only speculate on the reasons for the smaller number of artists entering and being shown in Cu3. The timing and coverage of the call for entries to the exhibition may have had some impact. Certainly the great hiatus between Copper 2 and Cu3 was a factor, as there was very little overlap in the artists who exhibited in both shows. And finally, as suggested by Eleanor Moty many students and established professionals are doing very exciting work in nonmetal jewelry and sculptural forms - with materials such as aluminum, wood, paper and plastic. The prospectus stated that the pieces had to be made predominantly of copper or copper derivatives. While this restriction may have been necessary to examine the state of the creativity and expression in the material and for historic continuity, it certainly was a limitation that needs to be questioned if this exhibition is to become a continuing one.

My purpose in this article is to describe what the exhibition did show, especially in some of the pieces selected for awards, compare the three exhibitions in general, and make some analytic observations about the field of metalsmithing and jewelry as indicated by what was and was not in the exhibition.

Selection for awards was based on "evidence of a consistent maturity of expression; a unified body of work showing a strong synthesis of concept, design, and technique. We sought work which was conceptually sophisticated, technically masterful, and visually fresh. In particular, we sought the distinctive and shunned the derivative" (Cu3 catalog, Jurors' Statement, p. 12).

While there was not an abundance of jewelry submitted to the exhibition, the very sensitive patinaed metal pins of Patricia Telesco (Huntsville, AL) are truly beautiful, functional (about 1¾ inches square) and intimately personal pieces. The five small enamel brooches of Celia O'Kelley Braswell (Makanda, IL) certainly acknowledge the breakthrough copper enamel techniques and expressions of Jamie Bennett, not as derivative, but much in the same way that the great abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky is referenced by the abstract expressionists of the 1950s. The sensitive and mature necklaces of Jan Yager (Philadelphia, PA) also deserve praise in the jewelry category.

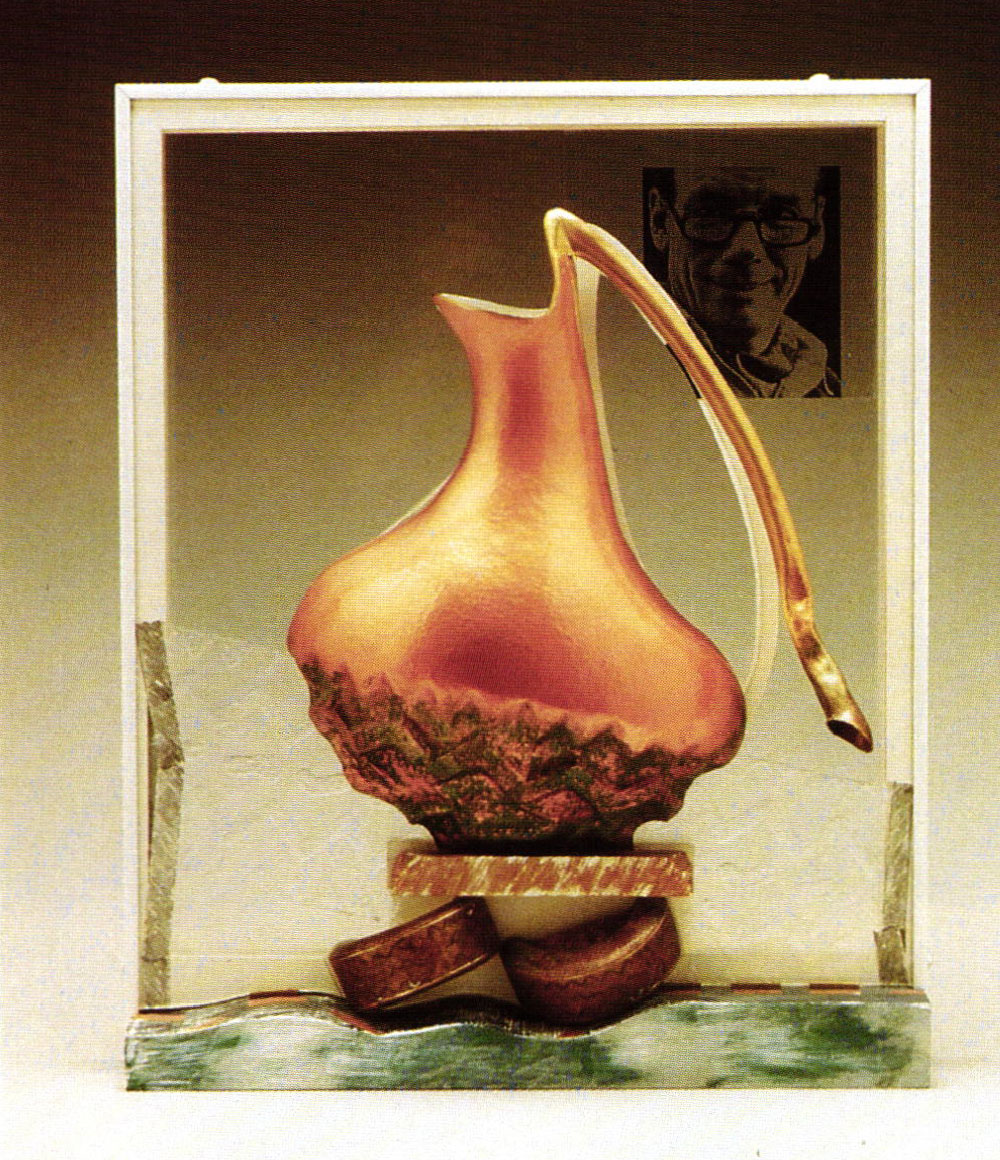

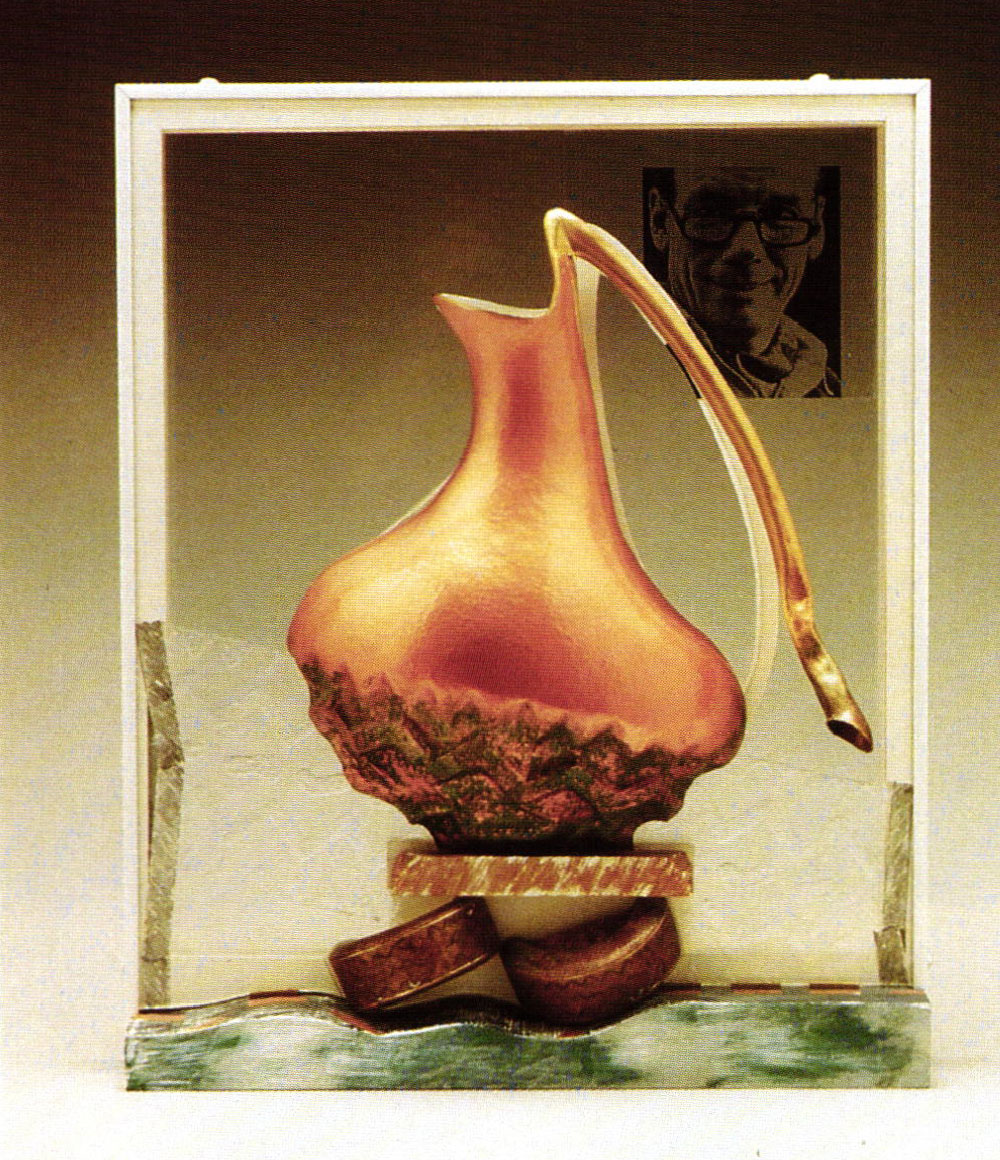

I was particularly intrigued by the two pieces of William Baran-Mickle (Pittsford, NY), Johan Rhodes Update and A Successful Season. Both pieces are approximately 20 inches high, both contain real vessels but used as symbolic forms, and both are presented as simultaneously framed and sculptural objects. Baran-Mickle is making art statements by reaching back to the recent and essential roots of metalsmithing and calling or recalling our attention to them. The Johan Rhodes Update takes the classic, quintessential functional pitcher form of "modern" hollowware, but roughly rather than smoothly finished, puts it on a pedestal, adorns it with frivolous squiggles and pseudo-fashionable post-modern motifs and colors, and then frames the entire composition in a deconstructivist, disjointed picture frame. A Successful Season is a tribute or memorial to the master artist/metalsmith Hans Christensen, a teacher of Baran-Mickle's at Rochester Institute of Technology. It makes reference to Christensen's important work with Georg Jensen and the strong influence that Christensen's style and teaching had in the U.S. The death of Christensen in an auto accident is evidenced by the heavy tire tread marks chased into the base of the copper pitcher and etched into the Plexiglas of the picture plane. A Successful Season refers not only to the life of Christensen as a teacher and metalsmith but to the end of that life and stylistic influence in U.S. metalsmithing.

These pieces are made for the artist/metalsmith and do for us what Warhol did for the art world when he took the Campbell's soup can and forced us to focus upon the common object in our environment as art. Baran-Mickle's pieces are wonderful and yet myopic examples of the self-reflexive nature of the contemporary metalsmithing and jewelry world.

Lucinda Brogden (Rochester, NY) was another artist whose work was fresh, very contemporary and yet deeply rooted in art history and the techniques and processes of metalsmithing. Her chased and repousséd pieces of sheet bronze (four were shown) are very carefully planned and yet chaotic-appearing compositions about people and events very important in her personal life. She uses a combination of traditional cold and Japanese hot pitch techniques to attain very sharp lines and great surface depth in the compositions.

Objects become symbols, especially in Phone Intrusions 2, where the sharply incised phone cord becomes the tangled but distant connection between her and her husband, then living in different cities. The actual process of the chasing and repoussé work becomes a ritual, almost a liturgy, for her as she works out and works through the life incidents she reveals in her pieces. Her compositions hark back to the early Italian Renaissance and show a chaotic fatness but vivid movement similar to that found in the painting of The Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello.

The tradition of pure beauty and formal elegance in precious and nonprecious metals throughout history is certainly upheld by the works of Stephen Walker (Andover, NY). His incredible 9-inch-high bowl (cover image) incorporates married metal, a variation of mokumé-gane and a Damascus steel type of pattern welding. The patterns of copper, sterling, nickel and bronze, while appearing accidental, are in fact careful, almost mathematically planned. The piece is actually number 33 in an extended series. I especially liked the edges because they show a real vitality and they contrast excitingly with the elegant but controlled crazy-quilt pattern of the bowl.

Walker is representative of the contemporary metalsmith/jeweler who makes a living from his work rather than reaching at a college or university. He effectively manages to produce fine works for sale at major ACE and other shows as well as to make museum exhibition pieces with the same integrity and techniques of his multiple pieces. It should be noted that he also exhibited two pieces in Copper 2 and both were sold from the exhibition.

The painted bronze castings of Rand Schiltz (San Jose, CA) presented some fresh forms and whimsical themes. They appear to be multiple piece castings (four were exhibited) that are joined together almost as if they were folk art wood constructions. The colors are light and lyrical, and the subject matter is very narrative and certainly erotic. Jurying from slides can provide some real surprises. Since the works are only about 14 inches high, the detailed and erect male genitalia on three of the pieces were totally unnoticed by the jurors when they viewed the slides. However, they were noticed by many viewers, a few of whom let it be known to the museum personnel that they were not pleased. To the credit of the museum director, the pieces remained on full view throughout the exhibition.

Bruce Clark (Tucson, AZ) presented some very impressive pieces in his four Beggars Bowls, all cast bronze with copper, gold and silver inlay. The bowls are thick - about ¼ inch or more - castings of human skull fragments and measure only about 5 inches in the longest dimension. The inside surface or concave portion of the skull bowls are inlaid with elegant and ancient-looking geometric patterns of colored metals. The pieces have an incredible richness and leave one with the intense desire to pick one up to feel the surface, heft and balance of the piece.

Among my favorites in the exhibition were the pieces of Keiko Kubota (Brooklyn, NY). Five of her very personal pieces were shown. Each of them is approximately 17 inches square and about 3 to 10 inches high. They begin with her birth, move to her school life in Japan, her first visit to the U.S., her wedding and finally her unknown future. The pieces are all correct: the size and scale are in harmony with the concepts; the techniques, imagery word stampings, incisings and coloration of metal all work together to present a unified expressive message of searching and progressing not only through life but through a skill and knowledge acquisition in metalsmithing.

The works of Chris Theodore Ramsay (Stillwater, OK) presented some real problems for the jurors and for many, many of the viewers. Two of his pieces were exhibited, both in a rather large, 32-inch diameter format. Both can loosely be classified as vessel constructed with alternating layers of heavy greenish patinaed copper circles and a reddish clay-like soil. Both also have dried and decayed found objects in them. The piece entitled Nature's Circle even incorporates a dead bird and what appears to be a braid of human or animal hair. These pieces were easily the toughest in the exhibition, and I was glad to see them as a contrast to some of the beautiful, polished and elegant forms.

David Alan Peterson (Saratoga Springs, NY) exhibited three fantasy instruments - two of them over 6 feet high - that are marvels of technique and technology from some other planet displaying an advanced technology that gives one the sense that all is well in some other world, if not in our own. Peterson's pieces also manifest a "harmony" of scale and technique that totally "fits" with their fantasy content and message.

The scale issue is one that constantly had to be faced in the exhibition along with that of "harmony" of concept and technique. While the pieces are excellent, I was left with a real sense of uneasiness of scale by the works of Robly Glover and Nancy Slagle (both from Lubbock, TX). Although elegant, the pieces seem to want to be much larger than they actually are.

The pieces of Dale Wedig (Marquette, MI) and Randy Long (Bloomington, IN) are a beautiful contrast in the use of painted copper. Both deny the nature of the metal with paint, but Wedig teases the viewer with carefully cut lines in the paint revealing the copper. His forms read almost like wood, but the edges surprise you with the crispness of metal.

Long's vessel forms are small yet wonderful works of architecture that display monumental height despite being less than 12 inches. This is the kind of control of scale that excites the viewer and shows one of the unique strengths of the metalsmith. The works of Robert Gehrke (Eau Claire, WI) and Beverly Penn (San Marcos, TX) also show an excellent command of scale that makes the message of these small pieces very strong.

In addition, the strong and mature vessels of Elliott Pujol (Manhattan, KS), Thomas Muir (Bowling Green, OH), Brigid O'Hanrahan (Philadelphia, PA), Robert Coogan (Smithville, TN), Claire Sanford (Bedford, MA), Sarah Perkins (Makanda, IL), Susan Ewing (Oxford, OH), Helen Shirk (La Mesa, CA), Patrice Case (Mt. Morris, NY) and Marvin Jensen (Penland, NC) added an elegance and historic continuity to the exhibition. They deserve serious consideration as the subject of an entire article.

The element of humor, especially the outrageous, that was so evident in Copper 2 seems to have been more subdued and controlled in this exhibition, but there is certainly a lot of joy in Oilcan Ballet by Lynn Whitford (Madison, WI) and a good bit of outrageous indulgence in Randall Reid's (Bloomington, IL) Ring Containers 3 & 4 and Michael Bennett's (DeKalb, IL) Bird Regenerator and the other two pieces in his Allusive Box Series. I was also intrigued by the trompe l'oeil candlesticks of Myra Mimlitsch Gray (Lafayette, IN) and the captivating ones of Boris Bally (Pittsburgh, PA), as well as the lively A-B-C Bowls of Jean Mandeberg (Olympia, VA). Good metalsmiths still go to extreme and almost surrealistic limits to make a statement.

As an exhibition, the show speaks to the field of metalsmithing and jewelry and simultaneously is a populist show. As a populist show it has been seen and enjoyed by thousands. For many, many viewers, it has been enjoyable, unintimidating and simply marvelous.

To the field of metalsmithing, it says that the qualities of the metal itself are very seductive and that the techniques needed in making works of art in this material can override the development of concept and expressive message. It reminds us that the harmony of scale, technique and message is all-important in a work of art and that metalsmiths and jewelers have a unique responsibility to strive for and to resolve this harmony. And while Cu3 was a wonderful exhibition, the copper shows are complete; another is not needed.

What is needed now is a comprehensive biennial metals exhibition that is not competitive but rather a carefully curated selection of the best and most exciting new work that is being done both by young artists as well as by mature professionals. Ideally the exhibition should be staged by a museum, with selections from the exhibition prepared to travel in the U.S. and abroad. I commend the Old Pueblo Museum and the contributors to Cu3 for their fine work. Now let's move forward.

A catalog for the exhibition is available through the Old Pueblo Museum, 7401 N. La Cholla Blvd., Tuscon, AZ 85741.

Robert L. Cardinale is an artist, writer and former president of the Museum of New Mexico Foundation in Santa Fe, NM.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Danner Prize 2005: Competition for Arts and Crafts

Competition for Jewelry Made of Silicon Carbide

1983 SNAG Platinum Jewelry Design Competition

2009 AJDC New Talent Award

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.