Al Pine: Conceptual Exploration

9 Minute Read

Al Pine has been a fixture at Cal State Long Beach for over 25 years, where he teaches with Dieter Muller-Stach. Such a long tenure has hardly dampened his enthusiasm for learning and experiencing his field, as well as teaching what he calls "survival skills," which involves not only imparting technical knowledge but also the impetus to use this knowledge in creative and imaginative ways.

His teaching philosophy also encompasses the passing on of an appreciation of crafts related to historical and contemporary technologies and the esthetics of their times in different cultures and countries. Pine's own search for new experiences through travel has taken him on sabbaticals all over the world.

An excerpt from a letter home during his trip to Indonesia is just a sample: "I've just come back from a two-day motorcycle excursion up to some mountain lake, temples and volcanos. Shared the experience with a young Swedish landscape architect whom I met since being in Bali. He was the one who drove the rented motorcycle. I navigated and gave ballast to the vehicle. It was really an exhilarating experience to be out in the most remote countryside, going through beautiful villages and farm lands. The people wave, smile, gave directions, sell you coconuts, bananas, batik sarongs, wood carvings, delicious food, a little friendly bargaining — but I always let them win. It's such a bargain already,"

A New York City kid in the mid-1950s, who thought that everything west of the Hudson was camping out, Al Pine has come to personify the crafts movement in California, where he has taught in an extremely successful program at CSULB since 1962.

ln her foreword to the 1971 "California Design Eleven" exhibition and catalog, Eudorah Moore noted:

"The crafts movement in California is one of extraordinary vitality at the present time, and is particularly interesting in that it exists quite separately from historic crafts movements or generally indeed, from crafts movements in other parts of the country. Totally devoid of indigenous folk arc roots, it represents, at its highest level, a conceptual and experimental probing of materials. Contrary to the community of the fine arts, this aspect of creative expression in this place and time, is uniquely free of the pressures of the marketplace, and most of the explorations going on are highly personal aesthetically, technically and, in certain cases philosophically motivated. There is a strong shift away from the thinking of the creation of the finite object towards evolving a totality of experience. Works take on a life of their own and become a palpable experience . . . . The development of the craft movement here, both quantitatively and qualitatively in the direction it has taken, has probably stemmed from two sources. One is the sociological development of the State. A strongly individual almost frontier syndrome of doing things oneself along with a broad lack of that preciousness which insulates the vision of fine art as an encapsulated separate experience, has been abetted by an educational system which has included materials exploration coupled with availability of tools and expertise, in art, industrial art and environmental studies departments."

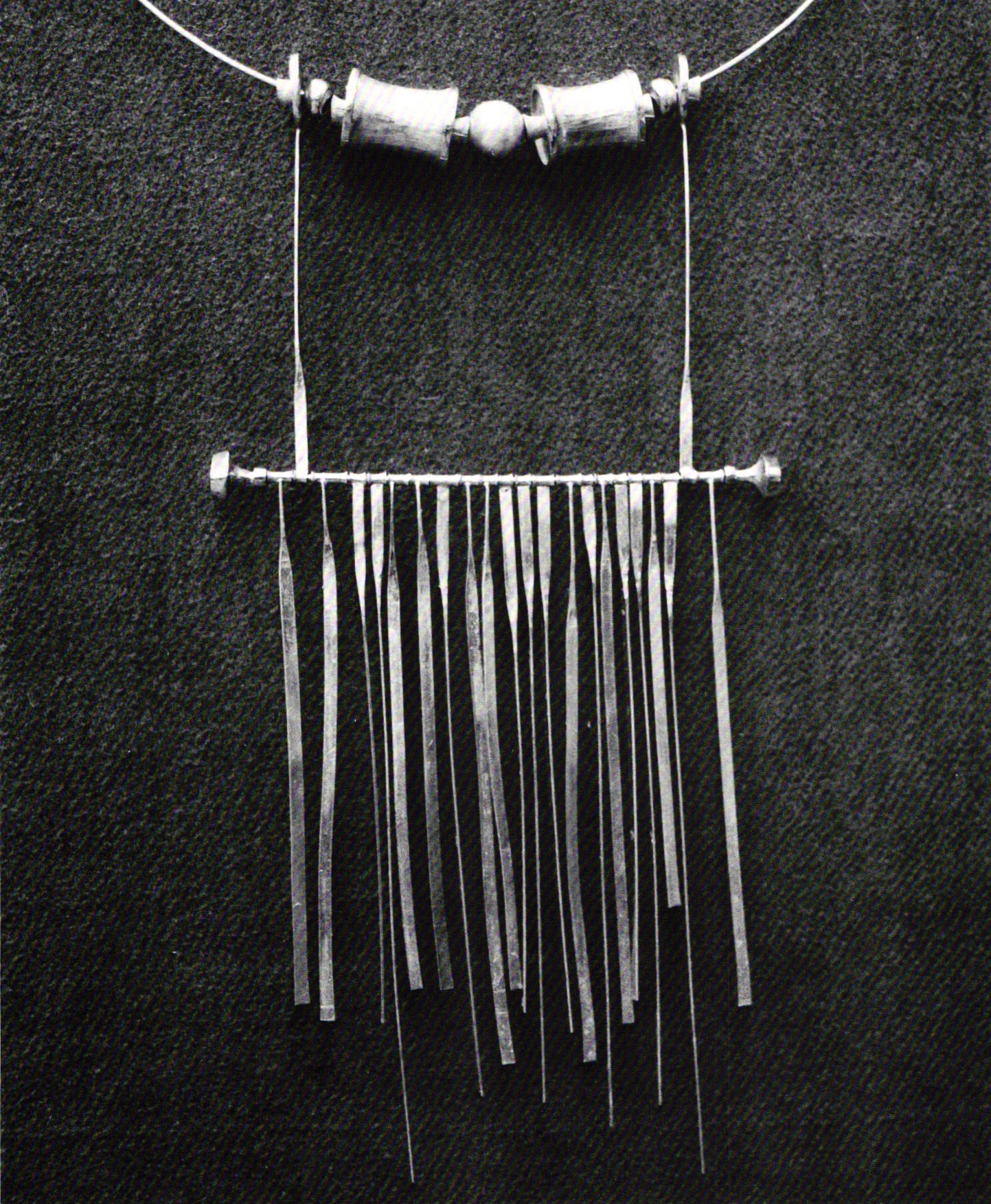

In the "California Design Eleven" exhibit, Al Pine showed a forged gold neckpiece with beads, garnets and pearls that exemplified this California crafts spirit. While gold, it eschewed preciousness, having a flexible, mobile quality, like a wearable wind chime, a sophisticated ethnic, hippielike, freedom nurtured in the 60s that became indigenous in the 70s. How Pine came to personify the California crafts movement is fundamental to why crafts have survived in the modern age and what meaning they have for a technological and electronic society.

"In our society today, identification and titles are essential in order to pigeonhole one's are of specialization; therefore, I am not a "jeweler," "silversmith," "metalsmith," "designer-craftsman," but a "maker of things.""

- Al Pine

from a wall plaque at the exhibition at Canyon Gallery, Topangha, CA, 1967

Al Pine grew up in upper Manhattan, in Harlem and the Bronx, and as a boy in the post-Depression years was fascinated with making things — model airplanes, wooden scooters from roller skates and other toys for street games. He attended an experimental junior high school in the Bronx, where he took sheet metal workshop, woodworking and printmaking, deciding early on that he wanted to be a wood carver or furnituremaker.

On his father's advice that these professions were due to become obsolete, Pine entered City College as an Industrial Arts major in 1951. His interest in making things, however, did not wane, and he remembers vividly his metalworking, jewelry and woodworking shops as highly satisfying. During these years at City College, in fact, Pine made fast friends with two other students, who together would form an important triumverate in the annals of metalsmithing history Fred Fenster and Bernie Bernstein.

The difference for Al Pine as an Industrial Arts major, however, was the learning process that he calls "shop conscious." The focus was not on the finite object as much as it was on deriving both technical expertise and understanding of design. Pine admired greatly, for example, the jewelry being done in Greenwich Village at the time in the studios of Paul Lobel, Ed Wiener and others, and he was perfectly willing, when asked by his sister, to reproduce pieces from Lobel's catalog. For Pine, this was a learning experience.

In fact, the Museum of Modern Art's publication How to Make Modern Jewelry as well as Kenneth Winebrenner's Jewelry Making were well-used demonstration models. The emphasis, then, was not so much on the elusive virtue of originality but on the importance of learning through getting inside other work, much the way a painting student might go through a Monet period, a Picasso period and a Pollock period in order to understand viscerally the workings of those minds. The experience of process and the mastery of making became paramount.

Al Pine's metamorphosis happened at Cranbrook, where he was accepted as a grad student in Industrial Design. However, he soon realized that the outcome of industrial design was a drawing from which someone else would fabricate the object. This was anathema to Pirie's desire for hands-on experience. What he did not realize was that his transfer to the Metals Department under Richard Thomas necessitated a change of attitude. His materials exploration now had to be channeled into an investigation that would lead to a personal contribution to the field. His background as an industrial arts major made him feel uncomfortable, inferior, and he determined to make work that would surpass that of any past graduate of Cranbrook.

Therefore, he poured over past theses, trying out techniques and mastering them, and established his own original thesis topic on forging techniques as applied to contemporary jewelry. He also experimented widely with casting, as classmate Don Wright had begun using the casting machine that had previously lain idle in the Cranbrook studio. An adjunct to the Cranbrook years was a Fulbright in Germany in the early 1960s. In fact, Pine was the first American silversmith ever accepted in Germany as a Fulbright student. In 1962, upon his return from Germany, Pine was offered the job of teaching general craft courses at California State University at Long Beach. He took the job, specializing in metal- and woodwork, as well as occasional three-dimensional design courses.

The brief summary of Al Pine's career is meant as background for an understanding of how his work came to be in step with the California crafts movement. The period when Pine did most of his jewelry was soon after he arrived in California, from the mid-60s to mid-70s. Much of the work is gold or silver, forged or cast, the directness of technique clearly apparent in the final piece. However, a complex imagery operates within the pieces, which is abstract yet somehow familiar, associative. This quality causes the work to feel amuletic, a personalized language of symbols that seem to have intrinsic power. Many of the pendants hang in elongated diagrams from simple neckwires. They have an airy, mobile, changeable quality, and appear light and free. Some of the elements appear to be found objects — keys or emblems, ankhs or beads — but they are part of Pine's vocabulary made from a rich, imaginative experience of the history of jewelry and ethnic artifacts. The primitive feeling allies many of the cast sterling brooches with modern sculpture.

Most telling, as Eudorah Moore put it, of Pine's evolution of his craft training to a "totality of experience," were his subsequent sabbatical leaves to Japan, the Middle East, Indonesia and China, which, while exposing him to a wealth of ancient and native techniques and work, curtailed his own jewelrymaking. As Pine expanded his knowledge and appreciation of the field, his interest in his own making of finite objects waned. In its place, his teaching capabilities were enriched by the addition of thousands of on-site slides of native metalsmiths working in primitive and sophisticated techniques as well as work from museums and private collections. Pine's legacy as an extraordinary teacher is the roster of graduates who have gone on to make names for themselves as teachers and practitioners in the field. Among them are Al Ching, Marcia Lewis, Gary Griffin, Joe Girtner, Chris Sublett, Linda Watson-Abbott, Carolyn Utter Radakovitch, David Keens, Joe Cornet, Irene Mori, Kay Yee and Hal Ross.

Al Pine's conceptual exploration of crafts involves continual probing into the role of the metalsmith and his working methodology. He has done this through extensive travels, yet he has honed his perception to be just as capable of finding an inspiration in his own back yard. An example of this is the story he likes to tell about Claire Falkenstein who one summer was invited to Long Beach as part of an international sculpture symposium. The school allowed her to work where she liked and she chose the patio outside the metalsmithing/jewelry studio.

One day outside his window Pine notices a woman pounding on a big-diameter copper pipe with a tiny ball peen hammer, physically squeezing the pipe down, and he muses sarcastically to himself that it would be useful if the summer school instructors would tell students that it would be ok to use a piece of steel and an anvil to do their work. After finding out that Falkenstein was actually working on a large fountain to be installed at the school, Pine became intrigued with her technique. For two exhilerating days, he investigated all the possibilities that squeezing and hammering copper tubing could provide, relearning his own lesson about material prejudice and the value of having an open mind even after 21 years of mastery.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.