American Holloware Changing Criteria

20 Minute Read

The expressions which have come to identify the pre- and post-World War II generations - Me decade, suburban frontiersmen, spoiled baby boomers, generation gap - are clear if perhaps overly stereotyped images. While encapsulating specific attitude changes in 10- or 20-year increments may seem synthetic, the division does follow actual trends. There is little doubt that needs, goals and values vary and are sometimes polarized from one generation to the next.

Each generation surrounds itself with paraphernelia which announce its identity and expectations. Statements of self are manifested in a complex structure of social and cultural reinforcement. Clothes and commodities, music and mania, religion and recreation are all subject to question and change. The differing attitudes are sometimes perceived as being quiet and tolerable or aggressive and intrusive. By instinct we righteously defend our own values and mores and question those which do not adhere to our standards.

Artists have been the observers, if often biased, and interpreters of our cultural condition. They clarify the bits and pieces of our culture and point out what binds us to our own history and what events have pushed us away to seek a new identity. That identity was clear to the artists beginning their careers in the era of Modernism following the Second World War. They felt that art should not mirror nature or society but rather that it should interpret them in a manner suitable to the medium. Further, this view of art allowed for individual vision which perceived not only positive but sometimes negative aspects of society. This responsible freedom led to diversity and resulted in an era of inventive and profound work.

In the midst of this exciting period modern American silversmithing was quietly developing. In an environment of enthusiasm and optimism ideas about form and honesty to one's own time were being assimilated by Americans from Scandinavia and to some extent from Britain.

During the 10 years following World War II a generation of American silversmithing educators were spawned from remarkably similar sources. A few events during this period would shape the identity of silversmithing and holloware, creating a style which has not noticeably changed to today. In this article I will address the issue of whether the values which governed Modernism in holloware after World War II are appropriate to today's generation of artists.

Holloware has developed basically three identities since 1945. Each has had a distinct impact on works coming out of schools today. First and most obvious are the organic and clean forms associated with Scandinavian design, ranging from the sober, sleek work of Hans Christensen to the complex skeletal forms of Heikki Seppä. Second, there are the structural forms which use natural and manmade elements as resources, such as Alma Eikerman's assymetrical structures which relate to architecture as much as to nature, and John Prip's most experimental works which reflect many of the principles of constructivist sculpture. Third are those who work in an historical context, reinterpreting images and iconography from earlier periods and adapting them to a modern context. Kurt Matzdorf's and Richard Thomas's ceremonial work are clear examples of this direction.

Let us now examine how these three identities developed. In 1945 the Rehabilitation Training Program in Dartmouth, New Hampshire, sponsored by the American Craftsmen's Educational council, was renamed the school for American Craftsmen. It was moved, first to Alfred, New york to become part of the Fine and Hand Arts Division of Alfred University and shortly thereafter it found a permanent home at the Rochester Institute of Technology. John Prip, who had been working in various silversmithing shops in Denmark, accepted a teaching position at RIT in 1948. Thus the course for RIT was set with a strong Scandinavian influence. This was later reinforced when Hans Christensen, also from Denmark, began teaching at RIT in 1954. Christensen, who had worked as a silversmith for Georg Jensen, came at the urging of Prip. He believed in the moral value of functionalism and the need for quality following the hard war years. To him quality meant simplicity in form and honesty to materials and process. Functionalism was an arm of the formalist doctrine, emphasizing form, not content or subject matter. According to Christensen, significant form was most important; representation was irrelevant. Subject matter was looked at as a denigration of the honesty to formal imperatives. "Bunches of grapes and hammerstrokes belonged to the decorative arts of the past," he noted later.

At its origin the Modern Movement was based on design integrity representative of its own culture and making good design accessible to a larger group. Christensen recognized, however, that modern silver table- and flatware did not have universal appeal and there was no point in "trying to unite silverware with social notions of good, cheap artifacts for everyone. "Unique modern silverware was made for those who wished to assert their individuality and had a sense of the present. Those who clung to the past were served by the silversmithing industry which perpetuated the traditional role of silverware as an heirloom. Therefore the Modernists' attempt to change the perception of what was significant in design and to ignore the eclecticism of the past had little early effect and drew only a select audience.

Both Prip and Christensen realized that the marketplace was not going to readily accept modern design. Instead, they educated their students to be leaders of this esthetic and to maintain its principles with the hope that it would eventually be understood. Christensen probably more than any other silversmith teaching in America emphasized optimum form in the Modernist context. Whether in silver sculptures or vessels, the resultant form existed as a coherent structural object with well-integrated elements. The viewer was offered a clear and precise visual experience. In examining Christensen's own work, as well as that of his students, we see an adherence to the modern formalism often referring to nature to provide order and structure. To achieve this fluid organic quality a suitable forming method was devised using the hammer and stake. These two tools have defined the shape of modern holloware as clearly as the wheel has defined pottery.

John Prip is not as easily categorized as Christensen. His work has followed a rather loose interpretation of functionalism, yet form is inevitably the primary concern. He most inventively used the tactic of mixing natural forms with manmade structures to create a broader variety of shapes, textures, contrasts and unlikely juxtapositions. His work shows a formal inquisitiveness as yet unmatched in holloware. He challenged the premises and rules of modern vesselmaking, charting his own course.

Of major significance in the training of American silversmiths were the Handy & Harman workshops, for these more than any other occurrence set the parameters of how holloware would be taught and what form it would take. In 1947 Margret Craver devised the Handy & Harman workshop conferences for the purpose of training American teachers in the art of silversmithing through stretch raising. She was motivated, among other things, by the belief that Americans could be as capable in this area as the Europeans and Scandinavians. Each of the five ensuing conferences, attended by approximately 12 participants, was led by well-known teachers such as William E. Bennett and Reginald Hill from England and Baron Eric Von Fleming from Stockholm, all of them functionalist-formalist oriented. Noteworthy from these workshops was the vocabulary they instilled in vesselmaking and the national scope of its impact.

Some of the participants to these month-long conferences were: John Paul Miller and Frederick Miller of the Cleveland Art Institute; Alma Eikerman of Indiana University; Robert von Neumann of the University of Illinois; Arthur Pulos, first of Illinois and who later started the Industrial Design program at Syracuse; Carlyle Smith of the University of Kansas; Virginia Cute Curtain and Richard Reinhardt of Philadelphia Museum School (now Philadelphia College of Art); Ruth Pennington of the University of Washington; and Earl Pardon of Memphis Academy of Art and later Skidmore College. Indirectly, others began their silversmithing experience through the film and journals which were produced. Richard Thomas began learning and teaching holloware at Cranbrook in this manner. John Prip, who had used other methods of raising, studied the journals to produce a bowl by the stretch-raising method for the first time.

As was noted in one of the journals, stretching was "a forming method particularly well suited to the development of contemporary designs of irregular and free shapes that call for unbroken lines and yet have the strength and richness of a thick edge." Thus the institutionalization of American holloware began.

With remarkable courage of these people broke from the traditional eclecticism in silversmithing. The works which resulted were fresh and varied. Each smith used his or her own interpretation and creative skills to give the work its own Modernist identity. These early pioneers maintained a sense of purpose in furthering the formal and conceptual vocabulary of the Modernist tradition which started at the turn of the century. Hans Christensen characterized this spirit as "a deliberate rebellion against the degenerating imitation of the styles of the past." These were honorable goals and the vanguard continually pushed at the boundaries to clarify their point. Functionalism was not simply a procedure to produce objects, it was a system of closely held values. Functionalism in design was believed to be right and true design.

As the teaching of holloware grew in American colleges, exhibitions became the method of communication. The citadel of silversmithing competitions for students was and still is the Sterling Silver Design Competition, conceived of and supported by the Sterling Silversmiths Guild of America since 1958. At the outset the image of Modern design and functionalism was perpetuated through this competition. It became the showcase for those schools which pursued the esthetic of functionalism and Modern design. In early competitions student designs were produced by professional silversmiths in hopes of creating impact on both parties.

Unfortunately, very few young designers were ever absorbed into industry from this competition. The American silversmithing industry was based on tradition and little had changed there since the beginning of the century. Nevertheless, the Guild saw fit to continually support the new ideas of Modernism and was genuinely concerned with the level of quality of this competition.

In the early competitions, Modernist vocabulary and doctrine became the way holloware was discussed. Success was evaluated within these boundaries. The criteria was significant form, and anything else was considered peripheral and irrelevant. Of course, this did depend on the jurors, but they were handpicked not only from industry, but also from the established instructors in the field, most of whom had had some connection with the Handy & Harman workshops or with Scandinavian training.

These early years of the competition without question were exciting and important for silversmithing. Forms were inventive and of high quality. A clarity of intent was apparent in the work of these young silversmiths who understood and believed in the principles of functionalism. Their instructors, some of whom had originated these principles, did not merely teach techniques. In the momentum of the day, the principles of functionalism were offered with such enthusiasm that its doctrine was embraced with genuine commitment.

What then has happened in the last 20 years in holloware? Where has the integrity of the work gone? We know what guided that first generation of silversmiths after World War II. There was a changing system of values, an attention to their own culture, the need for simplicity and clarity in a quickly industrializing society and, if for no other reason, the natural cyclical development in the arts.

Unfortunately, what has happened since then is a greater enthusiasm for the Modern style than for the act of individual invention and commitment to a principle. The spirit of functionalism has degenerated into a system of techniques and arbitrary anonymous forms. Consider the hundreds of metal vessels which have been pushed out one way or another to imitate natural forms or pay homage to the Modernist sculpture of Henry Moore. Ironically, the Modern style has become just one more on the list of historical styles which one can imitate. The style is emulated since the guidelines are there, but without the understanding of why one makes things. As a result, most of today's holloware objects are unimportant and superficial because what should be emulated is the spirit in which the work was made, not the style.

The post-WW II silversmiths saw their lives differently, which altered their world view from that of their fathers and grandfathers. They no longer wanted to represent their ideas eclectically. They divorced themselves from that attitude, emphasizing a new purity. No longer did they want to represent the burdens of the 19th century or the frustrations and gloom of the 30s and early 40s. How can we possibly relate today to the spirit of formalism in holloware that occurred during the period that followed the Depression?

There must be honesty in the making of an art object, whether it is a painting, a building, a ceramic bowl or a metal vessel. Honesty is an act of awareness and a willingness to take risks in presenting a point of view. There has been misuse of and/or little adherence to this principle within the current repetitive approach to holloware.

Somewhere during the last 20 years we have let pass the opportunity to clearly represent our time and our world view. Modernism has become a veil, obscuring and neutralizing ideas and issues. Objects are being produced which merely imitate the Modern process, although they try hard to proclaim their status as art or worthy form. Such a strategy inevitably produces boring objects. One artist who represents the contemporary culmination of Modernism is Helen Shirk, particularly in her work of the mid- to late-1970s. Although it is perhaps past the point where any more significant statements can be made in the Modern idiom, it is nevertheless noteworthy to recognize her work. She is one of few who pushed beyond the foundation of the early silversmiths. Emerging from the influence of her teacher Alma Eikermann, she compensated for the reduction and sterility of raised vessels by interrupting them with geometric constructivist planes and surface variations. This style is as identifiable to Modern holloware as the more sober organic style and a dominant direction in American silversmithing. A particularly noteworthy example is Decanter, 1979. As she has stated, her interest was in "the feeling of energy created by the projection and penetration of the forms, contrast of pattern against plain, edge against fluid surface, space against mass."

True to formalism the work is about form, not content. Shirk recognized the Modern parameters and challenged them. In retrospect, it seems inevitable that someone with significant abilities would produce an object which would both manifest and comment on Modernist principles. It is interesting to note that Helen Shirk abandoned holloware shortly after completing Decanter, concentrating instead on jewelry, which she finds more expedient to exploration of form.

As stated above, there were other identities besides Modernism in the decade immediately after World War II. Those who drew from historical forms and subject matter, both in their own work and in their teaching, were more decorative in their approach. Kurt Matzdorf, for one, was such a maverick. His work comprised primarily ceremonial vessels and sculpture for liturgical purposes, lending itself to representational images and inconographic styles. Matzdorf and others like him were uninhibited admirers of historical resources and romantics for the return of classicism. They adapted these forms and imagery to their own sense of modernism. This small group was not so much against Modernism but for historical continuity and respect for tradition.

This respect and understanding has since, unfortunately, come to mean embracing the work of another culture or period and merely reciting it in a slightly altered fashion. Such superficial homages offer little, having nothing to do with our culture and eschewing a point of view. Drawing from the past should mean using those qualities, purposes and relationships which are relevant to us today. The abhorrence that early Modernists had for meaningless eclectic assemblage should be recognized as valuable. Much work today takes a little from the past, throws in a bit of Modernism and is finished with a taste of a new technique or material. This has nothing to do with substance or invention of new form. It is more of an uninspired smorgasbord.

Whether one is a Modernist, Post-Modernist or Anti-Modernist, it is not enough to merely memorize the language and use it without understanding or believing in its principles or its history. This then is where the problem lies. Holloware's identity has been preserved and perpetuated through a single evaluative criterion, functionalism. Whether organic, structural or eclectic, the final piece is judged by whether it is appropriately Modern. This way of thinking was right in the early 40s, but is it significant to teach in the 80s? Emphasis is and has been on a now predictable set of forms and resources. The hammer and stake was and is the formative language of holloware, occasionally embellished with constructed elements or decoration. We find the same assortment of hammers and stakes exist from school to school. We all give the same instructions on how to use them to make holloware. We crimp, stretch, raise, seam, shellform and planish in a fixed vocabulary of conspicuous process, defining and limiting opportunities before we begin. To think that the alteration of stake shapes or doubling their amount will create a rebirth of the form inventiveness is not to recognize the fundamental problem. Even the attempt by Heikki Seppä to define a working language of established form does not alter the result. To fairly evaluate holloware today we must ask ourselves: "Are Modern forms adequate to represent the diversity of interest today? In fact, why do we limit the value of holloware to form alone? Is subject matter or content still insignificant in relation to form? Are representational images still taboo?

This means of expression must suit the idea and the time. Convention has constantly been challenged because of its relevance to changing cultures and needs. The Modernists found the eclecticism and impurity of late 19th-century industrialization to be an anachronism and reacted against it. We should examine Modernism in the same insistent manner.

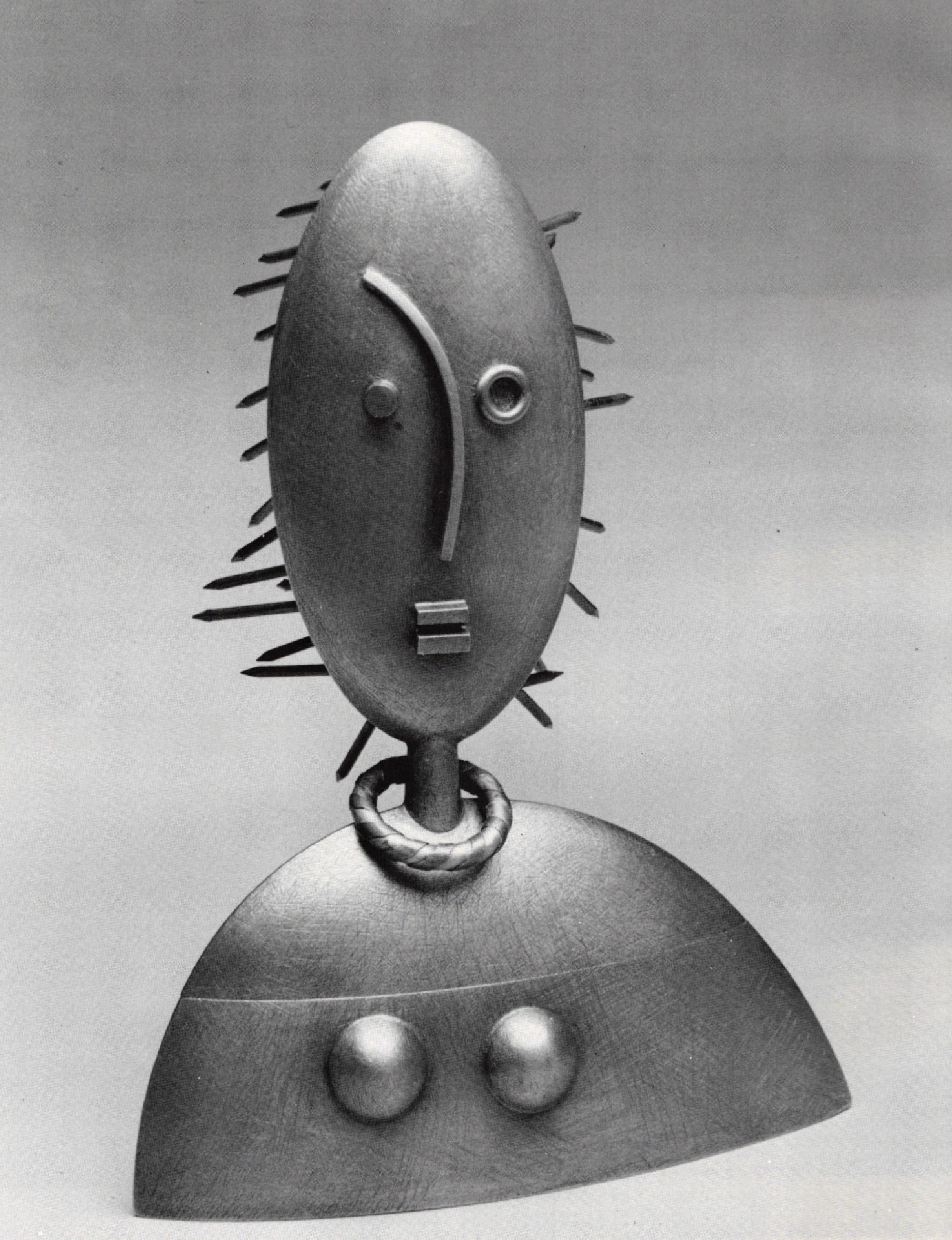

Who has found an alternative to Modernist holloware? There are works today which challenge the doctrines of functionalism, that suggest new relationships of form, subject matter and content. In my view Robin Quigley's Container is one such piece. It would not succeed if judged in the context of formalism-functionalism. In fact, her work pokes fun at formality. It is subjective, explicit and casual. There are quirky stylized details and a sense of impulsive input rather than predetermined criteria. While the work still falls within the historical parameters of metal, it is not within the Modernist doctrine. Neither are the playful geometry and storytelling of Randy Long's ceremonial vessels, nor the archetypal spiraling bowl by Janet Prip. They do, however, offer a solid base for another way of thinking about holloware and the vessel form.

Randy Long's vessels seem to have an appetite for the unlikely or unreal. The work does not fall into the self-indulgent analysis of dreams but acts as a metaphor for those experiences which reality does not offer. Although playfully composed, her magical and fantastic momentos are solid and specific. The use or precarious form relations reinforce the mystery and sense of an in-process performance which is central to her intent. Form in this case is a vehicle; content is the imperative. Janet Prip's work invokes simple forms and primitive patterning, which appeal to the child in us. They convey the unabashed quality or a doodle. Neither Long nor Prip believes holloware has to be polite or self-consciously technique-intensive. Their work is fresh and not intimidated by any traditional context.

In terms of functional vessels, a few artists have emerged recently who once again have a sense of responsibility, who are concerned with offering something to the field rather than taking from it. Their work is not hyperbole and technical showmanship, but offers personal substance and meritorious design. There is a sense of coherence and visual pleasure derived, for example, from the crisp geometric simplicity of Charles Crowley's espresso service or the understatement of Linda Hull's Basket Forms. Both Crowley and Hull have opted for spinning, an appropriate technique to achieve their geometric forms. They also employ lacquers and enamel paints to add a dimension of life and color to the otherwise cool grayness of silver and aluminum.

It is refreshing to see works which address the vessel form and emphasize its structure by patterning and coloring. Other artists have taken vesselmaking out of the strict context of utility to make us more sensitive to the psychological and ceremonial implication of the object. Christopher Allison and Edd Deren's vessels make use of "appropriate" technique to best exemplify their intent. Their pieces are rich not because the surface is polished, chased or patinated, nor because the form is properly raised or the solder seams invisible. The work has strength because the surfaces are finished with sensitivity to the concept.

Technique is then a significant element in the development of holloware. But just as a ceramic bowl does not lose consequence because it is handbuilt rather than thrown, or a piece of sculpture because it is constructed rather than cast, let us not then define holloware by the hammer and stake alone. This sort of restriction is not appropriate to today's pluralism.

In this context other inspired works come to mind which are worth noting. Particularly the Alessi collection of coffee and tea services designed by architects (see Metalsmith Spring 84, pages 36-38). While they all might not be functionally precise, they do offer fresh alternatives, incorporating inventive architectural resources.

While we could theorize that the work mentioned above marks a beginning of a revitalization for holloware, caution should be observed in this search for newness. Substantive innovation should not be confused with superficial alteration. Attaching titanium details or New Wave patterns to forms may be new, but it is as accommodating and shallow as any period or cultural adaptation. Why should we dilute our own intentions with someone else's identity?

Another pitfall the metalsmith faces is the relentless hunting for "tricks," techniques and processes, often pursued with a vengence unknown to any other artistic discipline. There is nothing wrong with seeking appropriate methods of expression, but a material is only a material and should not be relied on to update an otherwise weak idea or form. For holloware to develop and exude the vitality it had 35 years ago, it must be infused with outside visual inspiration, not more material and imported techniques. We must be able to look into ourselves for our own uniqueness without self-indulgence. It is only with that combination that we will again see vitality in this medium. We have been living on the sound foundation estabalished by Margret Craver, Hans Christensen, Alma Eikerman, John Prip, Richard Thomas and others for too long. As Christensen stated a few years ago, "What is new is not good, what is good is not new." It is time to rethink and revitalize holloware.

Notes

- Hans Christensen, "Observations about Design and the crafts Movement in Denmark, 1880-1980," notes from "American Metalsmithing and Jewelry in the 1940s and 1950s," a research conference, 1982, p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 11

- Information courtesy of Robert Cardinale through the "American Metalsmithing" research conference, 1982.

- Handy & Harman, "Contemporary Silversmithing," 1952, p. 4.

- Ibid., p. 15.

- "Contemporary Silversmiths" exh. cat., St. Petersburg, FL: Museum of Fine Arts, 1979, p. 28.

- Op cit., Christensen, p. 12.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.