Arline Fisch: The Art of Wearable Magic

12 Minute Read

The most intriguing characteristic of Arline Fisch's work, particularly the textile constructions, is their utter transformation when worn. What may appear as simple, even simplistic, knitted or woven metal undergoes a transubstantiation as it is put on the body, it takes form, animated by movement and light.

This artistic completion through wearability has received varying consideration by American jewelers. In the 70s, American jewelry was generally large, visually and technically complex and often so heavy as to be only marginally wearable. Fisch's work of the period is large, but always engineered with the wearer in mind.

Fisch makes jewelry because she in intrigued by the dramatic potential of objects that are enlivened by bodily movement. She has also participated in the trend toward demystifying jewelry as a precious, technically complicated status symbol through her integration of traditional and commonplace materials and her direct methods of construction.

Fisch's interest in the arts began early, with a fortunate childhood in New York City where exposure to the arts, theater, music and dance was constant and compelling. Saturdays were spent visiting museums, going to the ballet or simply absorbing the environment, instilling a permanent taste for the city's delights.

Fisch attended Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, a small women's college with a strong arts program. She majored in art education, studied art history and did studio work in painting, but very little in crafts. As she had planned to teach at the college level, and needed a masters degree, Fisch then went to the University of Illinois, Urbana, for graduate school. She was searching for her particular niche in studio practice. An initial major in painting was abandoned after a semester and she shifted to crafts, working in ceramics and metal. Ceramics she eventually disliked, but metal attracted her interest and enthusiasm. A year and a half of metal work formed part of her degree and proved the start of a lifetime commitment.

At 23, fresh from graduate school, Fisch was hired by Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, where for two years she taught drawing, painting and design. The college was near to jewelry manufacturers and many small studios. Fisch was able to rent space in a small workshop, where she could work at nights and on weekends. This period established the routine she follows to this day, combining a full-time teaching career with the continual exploration and development of her own jewelry.

A fortuitous opportunity arose in 1956-1957, when Fisch went to Denmark on the first of three Fulbright grants. She was accepted into the Kunsthaandvaerkerskoln (School of Arts and Crafts) in Copenhagen, on the condition that she learn to speak Danish! Scandinavian silver design had been revolutionized in the 1930s, and by the 50s it was considered the best in the modern world. There was initial resistance to the idea of an American at the school, as the Danes made it clear to Fisch that they thought Americans came only to steal designs and set themselves up in competition.

Hoping to study both ceramics and metal, she managed to negotiate an unusual program. She attended ceramics classes in the morning, then joined the Goldsmiths' School in the afternoon, and studied Danish in the evening. She went to a special class on Fridays where the jewelry students learned silversmithing. It was a somewhat frustrating time, as the Danish students who already had technical skills were learning design and rendering. Having design and drawing skills Fisch wanted to learn how to make things. A fortuitous meeting with a school director, Bernhard Henz, resulted in an invitation to work as a guest designer in his large jewelry fabrication studio.

The Fulbright period finished in 1957 with Fisch's first solo show at the U.S. Education Foundation in Denmark. She had then received both a grant renewal and a job offer at her alma mater. Skidmore Arline chose Skidmore, arriving home from Denmark with a new lexicon of skills and ideas, prepared for a position teaching design, art education, lettering and eventually weaving.

During her four years at Skidmore she continued developing her identity in jewelry The college sent her to Haystack to learn weaving with Jack Lenor Larsen and Ted Hallman, introducing a new medium and sparking an involvement with fiber structures and, in particular, pre-Columbian textiles.

In the fall of 1961, she accepted a position to teach jewelry at San Diego State University. California at that time seemed like the end of the earth" to her; the move there was an adventure and a challenge.

Soon after moving to California, Fisch was offered her first solo museum exhibition at the Pasadena Museum of An. Invitations for solo shows were rare, and she took the opportunity with enthusiasm and commitment.

She had been working hard to develop her own idiom jewelry design, and to shake off some of the Danish "morality" about what good design should be.

The preparation for the 1962 Pasadena show produced some of the first pieces she felt were thoroughly her own. The "garden" pins and powder box were improvisational rather than preplanned—related to sketching and free composition. She made numerous parts, then made environments and created scenarios within them. The "garden series" was the first use of narrative imagery, to which Fisch has returned on several occasions. These works were followed by jewelry and handheld objects in silver with wood inlay—still somewhat narrative, but with a more abstract, architectural reference.

A study trip to South America in 1963 had an important esthetic impact on her work. Costa Rica, Colombia and especially Peru were particularly significant in revealing a quality and simplicity of making that stood in marked contrast to her earlier experiences. In Denmark, she found that, although the designs were simple, the construction was often technically complex and had to be technically "perfect." Technical perfection was not Fisch's primary interest or goal. In South America she found work that was vital, lively and direct; technical competence as evident, but not as an end in itself. Fisch found the experience a liberating one, giving her "permission" to work directly and in technically uncomplicated ways.

The influences from the trip found reflection in her jewelry. By 1964, Fisch had made reference to the form of language of the pre-Columbians, as well as to their structural and technical concerns, in particular, the use of dangling elements that moved and caught light.

She also began to incorporate weaving in her jewelry. The first pieces were bib-shaped, woven yarn, with trapped silver elements. The designs sprang from a plurality of sources—African, South and Northern American, investigating in detail and interpreted in a personal manner. She began to think about structuring metal in woven forms—an idea to be later developed in depth.

A second Fulbright to Denmark in 1966 began the next significant period of development. Fisch was by then more committed to her work and more specific in her needs and interests. This time she rented studio space and studied chasing one day a week at the Goldsmiths' School.

She had proposed to focus on decorative objects as well as jewelry. A special arrangement at the National Museum in Copenhagen allowed her access to the museum's collection stores. Her investigation included study at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and an extensive European tour. Folk and costume jewelry in the Benaki Museum in Athens reinforced her thinking about the nature of jewelry and ornament and helped consolidate the directions her own work was taking.

Fisch's work showed dramatic developments during this period. The language and technical skills of chasing were employed first in a mirror, then in wine cups, as she expanded her interest in decorative objects. She wanted to increase the scale of her jewelry, and access to huge pitch bowls in Copenhagen facilitated the new size. She produced some of the work most clearly marked with her personal design sensibility, including very large, chased, articulated silver body ornaments and the first winged pieces. She began adding leathers to the work, first in a blue and silver woven bracelet. The period set the stage for many later developments in both iconic imagery and scale. Fisch was using natural forms such as butterflies, which then developed into winged faces and torsos reflective of early American tombstone angels. These works were particularly important, as they expanded her vision and convinced her that she could do anything she wished with jewelry.

The period 1966-71 was marked by extensive travel. Dividing her time between California, Peru, London, and Copenhagen, Fisch mounted a major exhibition at the Kunstindustrimuseet (Museum of Arts and Crafts) in Copenhagen in 1967, followed by solo shows at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, NYC and Museum West. San Francisco in 1968. She was made a full professor at SDSU in 1970.

Offered a solo exhibition at Goldsmith's Hall, London for 1971, she spend a sabbatical year in preparation. The exhibition included large body pieces: belts, woven, winged and feathered pieces, as well as objects. Goldsmith's Hall purchased two pieces for its permanent collection.

Fisch returned again to San Diego, and after much thought about where she would be permanently based, decided to build a large studio at her San Diego home.

The crafts movement was beginning to interest publishers when in 1972, Van Nostrand approached Fisch to write a book. She considered the prospect while on a lecture tour of Australia. The tour had considerable impact on the Australian crafts community and convinced Fisch to undertake the book project. She spent a year making samples and finished pieces, taking photos and preparing the text. Textile Techniques in Metal was published in 1975, and has become a standard text for those processes.

In 1975, Fisch was a visiting professor in the new Program in Artisanry at Boston University. She was continuing her involvement in textile processes, and that year produced one of her major career works—a dramatic woven and knitted silver and gold ruffled neck collar. This piece blurred the boundaries between clothing and ornament and evidenced a consolidation of her ideas and forms.

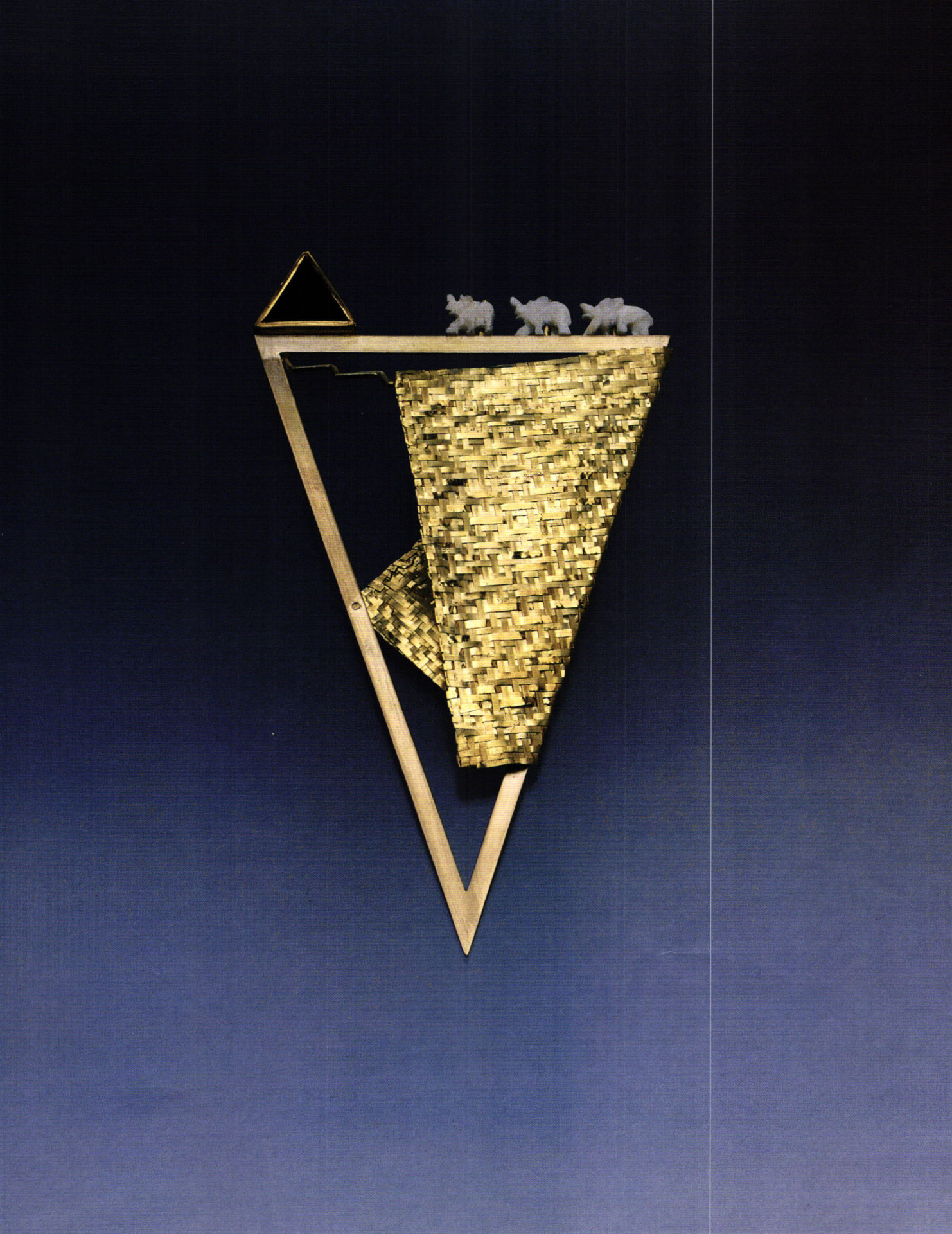

In 1978, she temporarily abandoned the textile work in a series of "elephant brooches." These works had an amusing narrative quality as tiny herds of ivory elephants marched their way over agate landscapes.

Fisch then decided to focus on the fluidity of ribbons and bows for her next major solo exhibition at Electrum Gallery, London in 1980. She spent a 1979-80 sabbatical in London with a Covent Garden studio, traveling also to Italy, France and Israel while preparing for the show.

Two significant works from the exhibition were a large silver bow and a sliver "handkerchief," complete with fine silver lace edges. Both pieces are gently amusing, with a slightly surreal, dreamlike quality. They bring a little smile when, on inspection, one finds they are not really what they seem.

Fisch has continued the exploration of "fabriclike" metal through the 80s, developing first a "flag" and then a "fan" series. These works returned to a large-scale format and employed the use of pattern on pattern—woven, printed and fabricated. She worked in a variety of materials: silver, gold, titanium, copper and aluminum.

In 1981-82, Fisch received a third Fulbright grant, to be a visiting professor at the Academy of Applied Art in Vienna. There she began to work with a technician on a knitting machine, producing "lengths" of knitted wire fabric to be later made into jewelry. Fisch also worked with woven sheet metal, producing a series of fan-shaped brooches and necklaces. She mounted a solo exhibition at the Museum Für Angewandte Kunst in Vienna at the close of the Fulbright period.

Returning to San Diego, she purchased a knitting machine and began modifying it to accommodate wires. She had decided that the flatness and evenness of machine-knitted fabric did not work well in silver. Colored copper, however, worked beautifully, producing a rich, dense fabric that was "warmer, and more human" than the silver.

Fisch mounted a solo exhibition of 75 knitted forms at Electrum in 1983. The works were exciting, but she felt there was still more potential to be investigated. She continued the development of knitted forms for a 1985 exhibition at the Helen Drutt Gallery in Philadelphia.

The knitted pieces became more dramatic, especially in color. Fisch was machine knitting with a resin-coated copper in brilliant hues and spool knitting in silver. She began experimenting with "body wraps," rather like a fine metal "skin" to wrap around the torso and head, continuing and expanding the nexus between clothing and ornament.

Fisch had been planning to do a woven gold collection for some time, as she felt that the softness and richness of gold are exceptionally beautiful in finely woven objects. In 1986, she began producing a sumptuous collection of woven gold jewelry, based primarily on squares and zigzags (see Cover).

An exhibition and major catalog of this work was jointly organized by Fisch and Doug Steakley of Concepts Gallery in Carmel, California. The exhibition opened in late 1987, then toured to the Wita Gardiner Gallery in San Diego, Electrum in London and Galerie am Graben in Vienna.

Wita Gardiner suggested that they investigate a dance performance and video that would incorporate Fisch's work with music and movement. The performance was to premiere at the opening of the woven gold exhibition in San Diego. Fisch had long been interested in the concept of performance, and began experimenting with reinterpreting aspects of her form language on a large scale—several feet in size.

After many trials, she developed the images of an open square box and a woven zigzag, reflective of themes from the collection. She worked collaboratively with a choreographer and a dancer to develop a program of narrative movement in space based on those shapes. In a manner reminiscent of Martha Graham, the dancer carried, and moved through and with, the two icons in a fascinating interplay of form and movement. It was a logical, yet delightfully surprising, continuance of Fisch's concerns with the body and movement.

Throughout the 80s, her works shows a cohesiveness and clarity of ideas and a consolidation of concept, form and process. It is work that is confident, dynamic and elegant, sometimes amusing, sometimes mysterious, and always addresses her conviction that jewelry is a "significant contributor to the joy, beauty and delight of the individual who wears it."

Jeannie Keefer Bell completed her M.A. in jewelry/metalsmithing at San Diego State University in 1979. She currently maintains a business in Fremantle, Western Australia, making jewelry, doing exhibition design and writing on the crafts, and is a Vice President of the Crafts Council Australia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.