The Art and Industry of Metal Furniture

13 Minute Read

In recent years, the design of furniture has invited experimentation by practitioners in a wide range of artistic disciplines. While a handful of architects has always designed the furniture and furnishings for their buildings, the practice is now far more widespread.

Since 1981, Progressive Architecture magazine, by default the most forward-looking journal of the profession, has sponsored a furniture competition that has distinguished itself chiefly by trying to espouse the notion that product design is both an area of serious research for architects as well as an escape route for their more conceptual fancies.

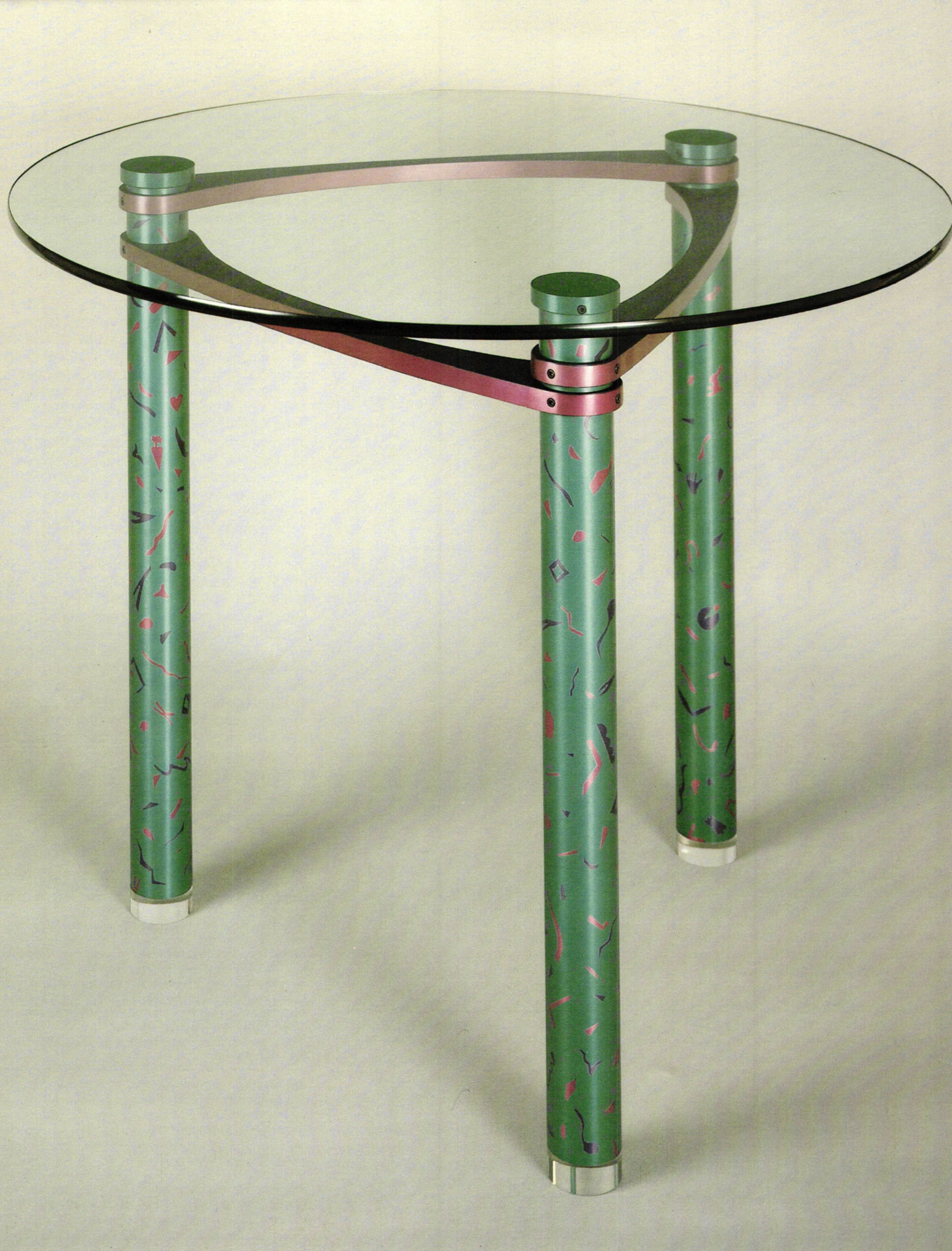

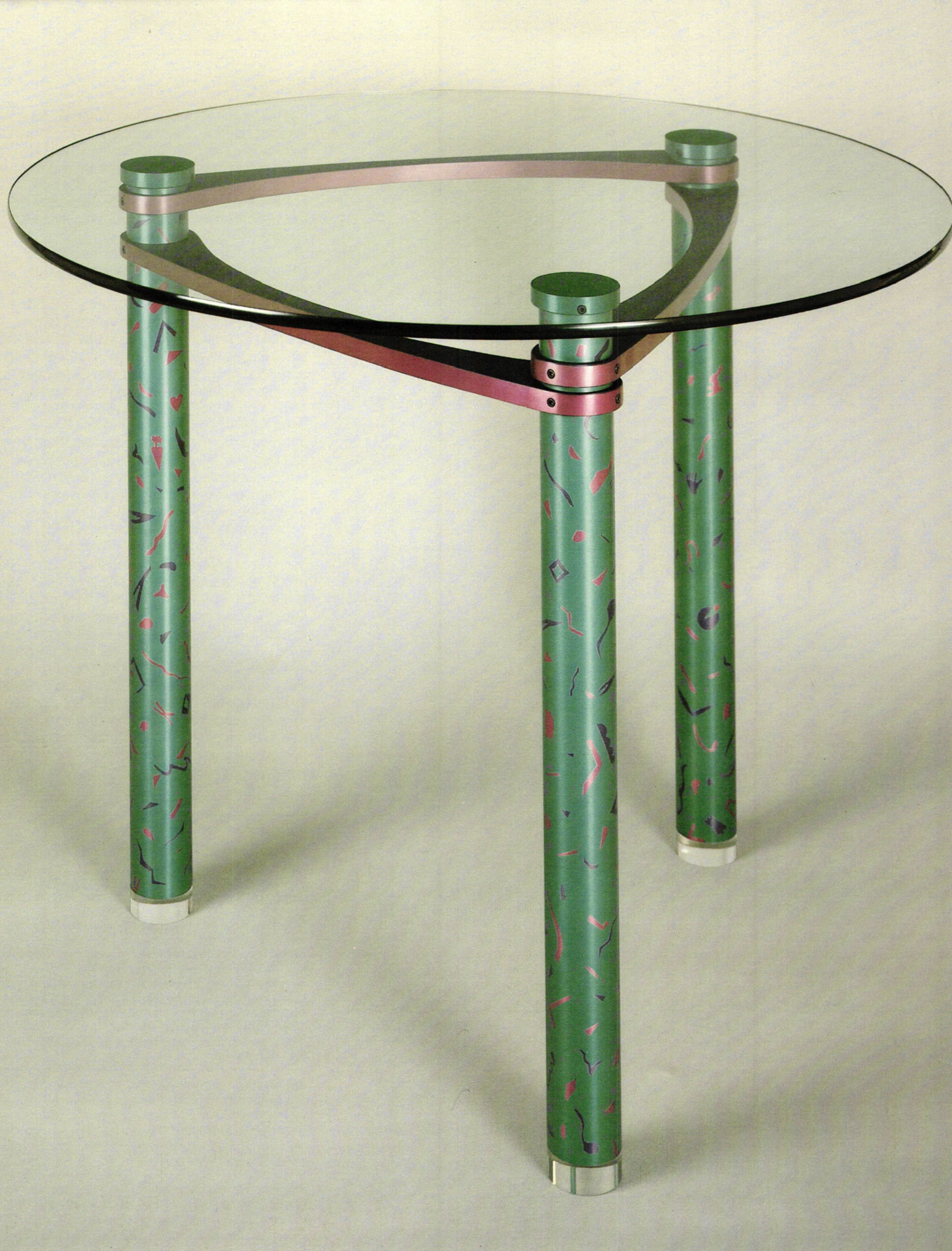

| Peter Handler, Game Table Anodized aluminum, glass, 36″ d., 30″ h. Photo: George Tate |

Sculptors, also, have found furniture a logical extension of their work. The kinetic, and often anthropomorphic, movements of Harry Anderson's sculptures translate easily to lamps; likewise, the granite and stone shapes of Scott Burton make for solid seating. And painters previously known for their expressions on canvas have been applying them now to furniture; and the painted, laminated and lacquered pieces that hare emerged from their studios have also interjected color and wit into the furniture industry.

Unlike the furniture of earlier periods, which had been painted largely for the purposes of obscuring poor craftsmanship or inferior materials, contemporary painted furniture blatantly celebrates the decorated surface for its own ornamental value.

The play on traditional boundaries of art, craft and design has not been lost on metalsmiths. By the very nature of their work, they are both a step ahead of other artists and craftsmen, and perhaps a step behind. To begin with, metalsmiths have always had to address questions of body orientation. Questions of how jewelry fits the body and accommodates its movements are essential to the design of wearable pieces: likewise, how a chalice fits the hand concerns many holloware makers. The vagaries of human form and movement are not news to metalsmiths, as they often seem to be for artists whose furniture is clearly to be looked at only.

On the other hand, metalsmithing has also tended to encourage a myopic sort of vision. Both its precious materials and small scale encourage an intensity and concentration that in the end may work to narrow the craftsman's focus. While benefitting the minute technical details of a single piece, such a focus may also be acquired at the expense of the larger ideas that are inevitably behind a serious or complete body of work. That the broad investigations evident in other crafts may come with greater difficulty to the metalsmith, however, is what makes them all the more welcome. And, once the metalsmith bas looked beyond the traditional confines of his medium to the areas of furniture and furnishings, the characteristic scrupulous attention to detail is clearly welcome.

Heretofore, metal furniture has largely been a product of industry; the use of steel or aluminum as a material has been predicated by the industrial techniques that make their fabrication economic rather than by the visual rewards of detailed handwork in metals that comes with the craft process. When the architect Marcel Breuer was inspired by his bicycle to bend steel for furniture, the furniture industry eagerly responded. Indeed, the volumes of undistinguished chairs subsequently constructed of several pieces of steel tubing and a wad of polyfoam upholstery might have been enough to make the architect think twice before making his contribution to the furniture industry. Steel and chrome tubing abounds on the furniture market today, but not for the concise lines and other esthetic properties it might promote, but for its ease of production and durability.

The metal furniture, however, that has been emerging from the studios of contemporary metalsmiths, has a different set of concerns. Consider the aluminum tubing used by metalsmith Peter Handler for the legs of a collection of tables. Handler addresses both substance and surface of his material. While the anodized aluminum legs rest solidly on the ground, a calligraphy of shapes and gestures floats on their surfaces, conveying a slightly contradictory lightness. Likewise, other strips of aluminum appear to float and wrap around the legs, attaching them. The play with weight and weightlessness, by nature of the material, is more in the metalsmith's domain than in the woodworker's or ceramist's, and it is one keenly appreciated in Handler's work. Coupled with his attentiveness to surface decoration, the tables are a significant departure from conventional uses of metal tubing.

Peter Handler is a metalsmith, and the refinement in the detail of his work clearly reflects his background in jewelry. "There's a certain kind of thinking you do as a jeweler," he explains. "The first thing any jeweler does when he looks at someone else's work is to look at the back. You pay attention to every small hidden detail. When you work that small, everything shows." Handler also points out that metalsmiths are more prone than other craftsmen to be flexible in their use of material. Woodworkers for the most part construct with wood, ceramists with clay, glassblowers with glass. Metalsmiths, on the other hand, by the nature of their profession, are offered a wider range of precious and nonprecious materials; a single piece may use sterling, glass, stones, aluminum, found objects. And this freedom with material is clearly something that will find applications in furniture and furnishings.

Although Handler now constructs furnishings only, the choice was made only after 10 years of working as a professional jeweler. "Good art is dated," he says. "It should speak for its own time. I would like people looking at my work in the future to know what period it stood for." Handler's first jewelry had been what he describes as "the mid-70s funk esthetic." His next jewelry series, however, reflected technology, the imagery suggesting a "humanized technology." This work was often made in aluminum and machined; an early series of pins were graphic constructions of aluminum and epoxy resin. When a designer suggested to Handler that the painterly surfaces might work as tabletops, Handler was intrigued and began to experiment with scale, where he has since stayed.

What especially appeals to Handler about the larger scale are the opportunities to do more constructivist, sculptural work. Not only does the larger size nurture innovation, but also the opportunity is afforded to explore spatial constructions that are clearly more limited in a two-inch brooch. That these constructions display a meticulous eye for detail and a flexibility in material, however, are vestiges of their origins in jewelry.

Louis Mueller, came to his design of lamps by a similar, though less direct route. Originally a silversmith, Mueller turned to sculpture in the mid-70s in an effort to move from "a recognizable subject to a more personal, conceptual understanding of forms involved." When, in 1981, he designed and constructed two lamps in brass, silver-soldered, with blown glass shades for his own use, he returned to the design of the utilitarian object.

Mueller points out that these two areas provide a balance: While the lamps are technically more difficult to produce, the sculpture is more philosophically demanding. Yet the technical refinement of the first benefits the second, while the more cognitive investigations made by the sculpture are reflected in the esthetics of the lamps. And both, he adds, use the skills he developed as a metalsmith, the soldering, the fabrication, the same attention to detail and craft.

"Jewelry has to do with restraint," says Mueller. "What you don't put in is as important, if not more so, than what you do put in. Often what isn't there is what you appreciate most. I believe in reduction." And this reductive sense of design is apparent in Mueller's early jewelry, his sculpture and his lamps. Yet it is not only the consistency that is apparent, but how this reductive esthetic is examined and applied differently in the three mediums. The sculpture has a presence of its own; often it goes so far as to be surrounded by a metal railing or bar that separates it from the viewer. There is nothing superfluous in its austere forms. Nor is there superfluity in the lamps.

These, however, are accessible, approachable, humerous and often anthropomorphic in their tilted, propped, leaning stances.

As a metals student of Mueller at Rhode Island School of Design, Todd Noe has also turned to lamps, but for more pragmatic reasons. "People liked the slick, lacquered finishes on my pieces," he explains, "but nobody bought the sculpture, so I tried to think of something else I could do applying the same esthetic." Because finish and color are Noe's focus, he uses metals that can be easily painted; colored brass and copper stalk support the fan of the shade in a play with form that is nurtured by the sculpture. Like Mueller Noe turns to lamps as a design exercise that further develops the innovations found in the sculpture.

The slick finishes of Noe's pieces do not immediately identify their material as metal. Howard Meister, on the other hand, uses steel purely for its structural advantages, and the material and construction of his pieces are immediately apparent. And, ironically, it is Meister who does not come from a metalsmithing background. On some levels, the pieces reflect this; on others, they don't at all.

Before designing furniture, Meister studied music, still photography, the Classics. And when he turned to furniture design, he explains, he simply started designing backwards. "I decided what it was going to look like first. Then I decided what materials it should be constructed in. The important thing to me was how it looked, the poetry of it." Meister's steel pieces are constructed with the most basic cutting and welding techniques, and perhaps for this reason—though he does do the work himself—he does not consider himself a craftsman. The pieces lack the detail in construction that is so evident in most pieces made by trained metalsmiths; they are not finely crafted, nor do they pretend to be. Yet they make the same inquiries into a contemporary esthetic as Handler's pieces; and though the answers they find are radically different, they too "speak for their own time."

Meister's high-gloss-enamel polished surfaces that have been brutally cracked, severed or otherwise broken reflect an esthetic that could be of no other design period. And his use of material purely for its structural value—rather than simply for its visual properties—has a certain integrity that is a part of the craft process.

Forrest Myers is a metal sculptor whose training was not as a jeweler, but "more on the industrial side." Myers worked in a small metals fabrication plant where he learned to cut, weld and fabricate metals. "I now do most of the work on the pieces myself and consider myself a metals craftsman," he says, and his steel, stainless steel, copper, brass and aluminum furniture endorses his statement.

Myers's pieces explore and exploit metal finishes. While it may be the combination and juxtaposition of different colors and textures that first draw the eye to his pieces, color is not used as surface decoration but as a statement of the material. Myers uses metals almost as a pictorial, rather than structural, device. Nevertheless, what the metal will do, the lusters it will take on, the surface textures it can achieve all predicate its use. While details of construction are clearly secondary in his work, this dedication to material is enough to qualify him as a craftsman.

The precise edges of Elizabeth Jackson's painted aluminum pieces are similar to those found in the work of Myers and Meister. The tapered shelves seem to emerge suddenly and spontaneously from the wall's surface, and both the pieces and the shadows they cast convey a sense of rapid movement. Through these pieces and the hooked rug that was made in conjunction with them, Jackson is continuing traditional folk art. "The shelves and chair have been cut out of metal," she explains, "like old weathervanes, and the hooked rug uses another folk art, though in a more contemporary way. "Jackson works with a blacksmith for the furniture; after she has made cardboard mockups, she works with him in cutting, folding, bending, in a process she finds akin to origami. Jackson's own background is as a sculptor, and her pieces reflect a contemporary esthetic. She is nevertheless quick to acknowledge the folk art traditions that her work relies upon and continues.

Her work, more than any other here, illustrates the cross exchange that so informs contemporary crafts. Her images are cross-referenced in metal and textiles; contemporary, they nevertheless recognize their folk art origins. That such a broad approach has found expression in a craft medium that by nature invites a more concentrated and narrow focus, is invigorating and encouraging.

Like Jackson, Karl Bungerz works in a variety of different materials. His tendency, however is to combine them in a single piece. The Conversation table, constructed of hollow welded steel and bird's eye maple, juxtaposes color, material, surface texture. Yet their precise fit belittles these differences, stressing instead the compatibility not only of materials but also of craft mediums. That woodworking and metalsmithing can dovetail so gracefully is a lesson valuable to practitioners of both.

In the end, this spirit of compatibility is the most endearing quality of this furniture: the compatibility of a jewelers' exacting approach with furniture construction; the compatibility of sculptural considerations of form to utilitarian objects; and the compatibility of traditional folk art to sculpture. That many of these most eloquent inquiries are being made in metal points out the possibilities for other jewelers looking to expand the scope and scale of their work.

More to the point, though, is that these pieces suggest that the distance between processes of art, craft and design is often imperceptibly narrow. As it narrows more, perhaps the tendency to assign categories such as "art furniture" or "craft object"—when what is being described is a chair—will diminish. Already vague, such terms serve only to further compartmentalize a design sensibility whose chief aim is to integrate. That such integration is possible and often, successful, is apparent in the work shown here.

Akiko Busch is a freelance writer and frequent contributor to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

5 German Jewelers Marketing Strategies

The Intimate World of Alexander Calder

The Legend Lives

The Meaningful Significance

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.