Betty Cooke: Total Design in Jewelry

6 Minute Read

In the Spring 1959 issue of Craft Horizons, entitled "U.S. Crafts in This Industrial Society," Editor Rose Slivka divides the American craftsman into three categories: artist-craftsman, production-craftsman and craftsman as designer-businessman. Clearly, in that era, Betty Betty Cooke was the exemplar of the production-craftsman, as Slivka goes on to define: "those who make well-designed, high quality utilitarian products, producing a limited amount of each design for a regular market. This craftsman may have his own shop or he may have certain stores which he supplies. . . He may also be an artist-craftsman."

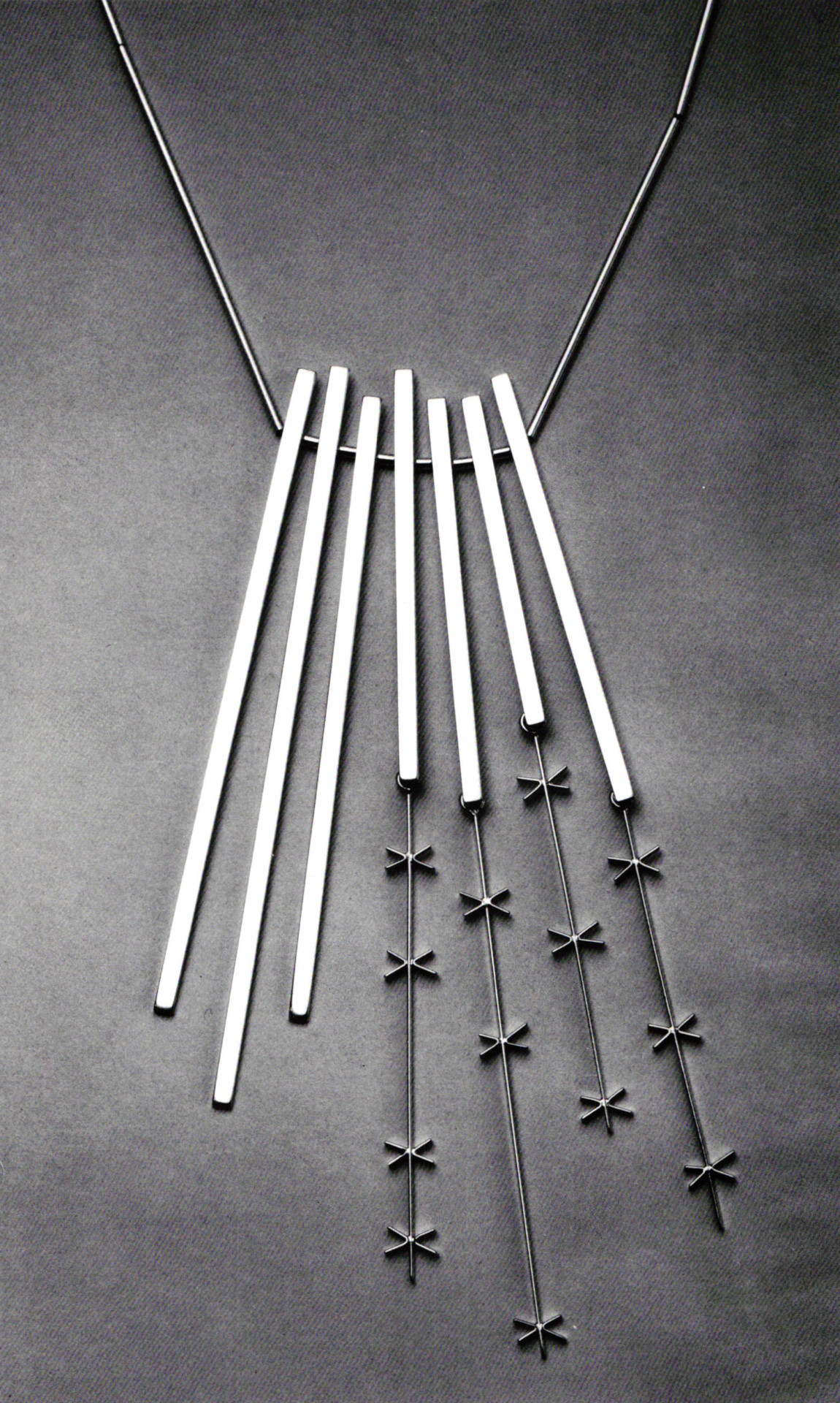

Over 40 years of making work of elegant design, superb craftsmanship and simple statement in jewelry, Betty Betty Cooke, who lives and works in Baltimore, Maryland, is a role model for those craftspeople whose esthetic and design ideals will not be compromised by the demands of a fickle marketplace.

We have asked Toni Lesser Wolf a better understanding of her determination and her success.

Betty Betty Cooke has designed and fabricated simple, clean, straightforward expressions in wearable metal adornments since her introduction to metalsmithing in the mid 1940s. She has sold her jewelry, which stylistically has changed very little over the years, directly from her own studio, storefront and now retail store in Baltimore, Maryland, from the beginning. It is bought today by the grandchildren of her first customers.

Betty Cooke is a designer with an integrated approach. While her Baltimore home—a converted carriage house—is filled with an eclectic mix of furniture and objects, from a sleek black Saarinen sofa to sedate Colonial Windsor chairs, her jewelry maintains a quality of purity and respect for material. She strives to convey warmth rather than accede to the anonymous coldness of much geometrically conceived jewelry and design. The forms tie together in a totality, regardless of the diversity of materials (silver and black plexiglass, for example).

In her work Betty Cooke instigates a dialogue between the spontaneous and the planned. She eschews the "organic" (her term) expressionism of Sam Kramer and Art Smith, both of whom she considers "fine artists" and not jewelers or designers, due to the barely wearable nature of much of their output and the fact that the additional richness of content in their work has the potential to detract from, or might compete for attention with, the wearer. Yet, on the other hand, she doesn't reflect the constructivist premeditation of Margaret De Patta, either. Betty Cooke's unique approach serves to bridge the gap between these two extremes.

Betty Cooke's jewelry is reminiscent of the Large, gestural brushstrokes seen in both her watercolors and her persistent doodles. Although rejecting the amoeboid shapes used by Arp and Miro, she still creates "action" pieces based upon the curve. Although she occasionally explores the straight line, as well, that line is always straining to bend—never is it precisely angular. Maybe the "warmth" of her pieces comes from her use of this gestural shape. Her modus operandi involves choosing a curvilinear form from one of her myriad sketches and allowing it to develop into other shapes. She then refines the design, often modeling the prototype in paper until it is perfectly evolved, the goal being a subtle gracefulness.

After the initial idea has been formed. media and process are the basic elements from which Betty Cooke creates her jewelry. Metal, wood, pebbles—all natural materials—are exploited until the limits of their intrinsic beauty are reached. Subtleties of color in stone striations and wood grains are emphasized and incorporated into the total design. Properties particular to silver are maximized. Part of the wire, for example, is left round, while the remainder is hammered to varying widths. Betty Cooke doesn't want the viewer to forget the wires humble beginnings—its inception through the drawplate.

In 1946, Betty Cooke received her B.F.A. from the Maryland Institute, College of Art. During her college years, she apprenticed to a local jeweler who taught her basic jewelrymaking skills. Directly after graduating, she was hired by the Institute to teach a course called "Design and Materials" that included jewelrymaking, welding and other metals skills to meet the demand of increased enrollment by the returning GIs.

As a child, Betty Cooke visited the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, whose ancient and medieval jewelry collections made an impression on her. Later, she also admired the work of Alexander Calder, Harry Bertoia, Ed Wiener and Margaret De Patta. She identified with the "good design" movement, typified by the "Good Design" exhibitions held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the 40s and 50s. She envisioned her product being sold through design stores such as Georg Jensen in New York (which eventually carried her bells and andirons) and Frasers in San Francisco, rather than art or craft galleries.

In fact, in 1948, she literally "knocked on the door" of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, a museum with which she was familiar due to their publication, Design Quarterly. Subsequently, her work was accepted into "Modern Jewelry Under Fifty Dollars" their 1948 exhibition in the Everyday Art Gallery.

Betty Cooke's philosophy is that jewelry and accessories should be integrated in an uncomplicated manner with clothing design Eventually, she had the opportunity to design jewelry for fashion designer Geoffrey Beane's runway shows in New York and Milan. A perfectionist, Betty Cooke laminated her own wood for necklaces and brooches, and even dyed her own leather for belts.

Betty Cooke's 15-foot wide by 20-foot deep two-and-a-half-story townhouse, which she bought in 1946, is situated on the "pastel block" in Baltimore, so named because residents paint their houses a different shade every year. The first floor of this house became her first design outlet. Here she sold Japanese folk art, Noguchi lamps, pottery by Nancy Wickham, Robert Turner and Karen Karnes, as well as her own jewelry, bells and andirons. It was a reasonably successful venture, eventually expanding into the mirror image house next door, which she purchased and broke through the connecting wall to create a larger floor space. She remained there until 1965, when she and her husband, William O. Sternmetz, opened The Store, Ltd. in the Village of Cross Keys, an upscale shopping mall not far from downtown.

Betty Cooke has always had a great love of nature, especially for animal, bird and floral forms. This imagery surfaces in various guises in her work from about 1950. Brooches and neckpieces from the early 1950s exhibit both increasing geometric abstraction and abstracted natural images. And, as did many of her peers in the studio jewelry movement, she concentrated on using sterling silver alone or in conjunction with wood, leather and enamel. An example of her reverence for natural materials is her incorporation of whole polished pebbles and colored natural pearls in her work of the mid-to-late 1950s. Later, there was increasing exploration into angular geometric shapes and experimentation with married metals. All of Betty Cooke's designs are handwrought and unique; she has never engaged in any production methods, save the occasional die-stamping of circular forms.

Betty Betty Cooke champions purity of design, nothing irrelevant or distracting. She believes that the design experience encompasses the excitement of doing something in the simplest and least complex manner. Her arm is to isolate from and help the viewer to read it clearly. Yet, she believes also that life should be full of warmth and whimsy. Her ideal home would include one stark room with only a bench and a spectacular view. "The rest of the house," she says, "should be full of personal clutter." Like the prospect of that home, her jewelry is irresistible; its appeal, universal, its simplicity and charm touching us all in a place that defies words and explanations.

Notes:

- See Metalsmith, vol. 6, no. 1, Winter 86

- See Metalsmith, col. 7, no. 4, Fall 87

- See Metalsmith, vol. 3, no. 2, Spring 83

- From an interview with the author, September 28, 1988

Toni Lesser Wolf is a jewelry historian, lecturer, curator and writer living in New York City.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.