British Jewellery and German Jewellery

6 Minute Read

On British Jewellery and German Jewellery, contrary to what one might infer about this exhibition, mounted at the Crafts Council Gallery in London last summer, from the poster, the two catalogs and the separate installations, there is little evidence of rivalry between these two bodies of work.

Not because this was considered an unlikely or illogical possibility, but for the simple reason, that, as organized, there was no competition. Through no fault of the British artists exhibited, the Crafts Council put together a mismatched dual show, performing, in my opinion, a disservice to the jewellery community here.

One needed only to compare the two catalogs to see what was in store. Catalogs can be polemical, discursive and insightful or pretentious and misleading But they are always instructive for what is included, what is implied and what is avoided. Also, for what is invested.

Here was a substantial German catalog, produced at considerable expense, three times the size of the rather slight British one. This, sadly, said much about the two government's arts funding policies. The German catalog contained four essays, which attempt to be serious, scholarly, historical, informed and analytical - in short, essays that attempt to contextualize the work on view in an intelligent and cohesive way.

In contrast, the British catalog contained a rambling, unrewarding essay by Graham Hughes, which, to me, is reactionary and out of touch, what with its surly and pompous pleas for artists to return to "the jewel" and "the precious," and its attempt to dismiss more recent experimental work.

This quotation from the essay will suffice to illustrate the point: "Jewels have always been a teaser to craft aesthetes: jewels involve too much money to fit into the ethical scheme of many crafts societies, for instance, the Arts and Crafts founded a century ago. Many devoted craftsmen have felt there is something wrong about wealth, and about the wealthy women who wear fine jewels. So, craft dissertations too often miss out the larger part of the jewel scene, simply because of its glamour, and are left with lacklustre pieces in base metal made by the poor for the homely." (Italics are mine.)

Then Peter Dormer and Jan Burney patch together what appears to be a collage of artists' statements, tied together with a few less-than-insightful observations about contemporary jewellery work in Britain. Dormer, too, has of late dismissed recent progressive craftwork. There remains Ralph Turner's foreword, which attempts to sketch out the brief of the British exhibition. It is not, he says, a survey of current work but an exploration of makers "working within the restraints of wearability and uninhibited by the intrinsic value of their materials."

This sounds fine, if rather difficult to define - an exhibition responding to the vocal demands of traditional (not conservative) jewellers, working in traditional materials, who have felt underacknowledged by the Council in its commitment to promote a more "avant-garde" body of work. While it must be agreed that this is long overdue, the exhibition would also have been a great opportunity to forego some "politically correct" choices in order to present a more focused and coherent show, which might have been a corrective to criticisms of past policy and to the charges of exposure.

Specifically, if the selector (Ralph Turner, presumably) had opted for an exhibition to match the Germans equally in work shown, developments plotted and illustrating historic continuities (three generations of teachers and students in the German case), a whole spectrum of underexposed and seldom-seen artists might have been included. As to the other constraint for selection, "working within the restraints of wearability," a debatable issue at best, again a large number of jewelers could have been called upon to contribute to make a much more informed and visionary show. What we are offered is a curious selection of makers, each of whom I personally respect and consider significant, thrown together in an unfocused and ultimately uncomfortable setting.

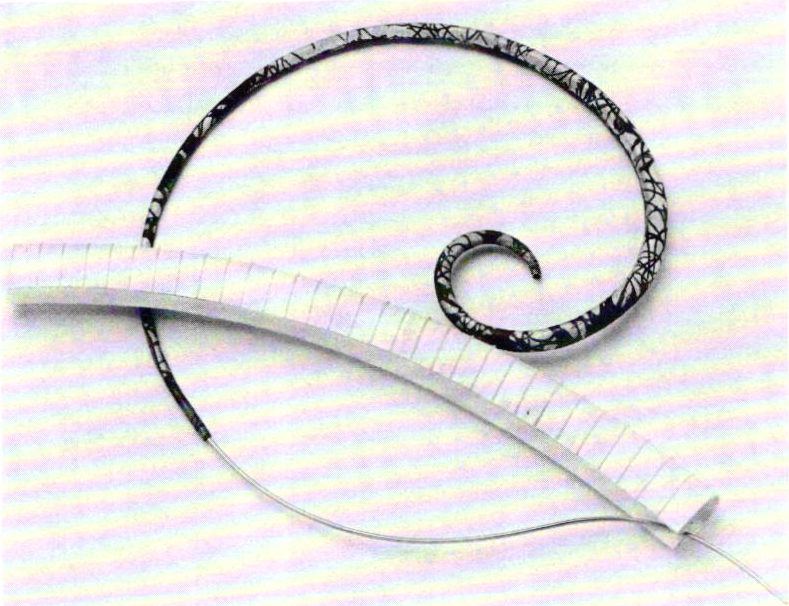

The problem for some was simply one of overexposure - David Watkins, Wendy Ramshaw - for others, it was incongruity of inclusion - Gordon Stewart and Jane Adam working in aluminum in a show defined as "precious-metal-based" and Elisabeth Holder, currently Professor of Jewellery at Dusseldorf Akademie, whose always superb work belonged by inclination, training and nationality with the German collection. The problem, in the case of Gerda Flockinger, however revered as teacher and early innovator, is that her work seems to me to be overrated and less than engaging.

Thankfully, Cynthia Cousens's work looked strong and came our relatively unscathed. With more clarity of vision from the selector, the artists tossed together in this show might have been pruned in order for alternative choices to be made. As considerable space was given over to Flockinger's work in the recent Crafts Classics exhibition and none to the seldom-seen Charlotte de Syllas, here would have been a prime candidate for inclusion, not to mention Eric Spiller, Kevin Coates, Catherine Mannheim, Catherine Swann, David Poston, Alison Bradley, Bryan Illsley or Breon O'Casey, for example.

Then, too, not all the important makers of the great 1970's explosion have abandoned jewellery. And while I applaud the inclusion of a new generation of artists, such as Maria Wong and Gordon Stewart, what about the possibilities of work from Hazel Jones, Richard Twose, Kim Ellwood, Brian Podschies, Maura Heslop, Clara Hoad or Mike Abbott and so on?

To make matters worse, the installation for British Jewellery was dreadful. The deathly grey colours and the badly executed plexiglass rod inserts holding the work should have been serious reconsidered.

The German work, on the other hand, while varied, generally displayed an underlying shared set of values: rigour, focus, intellectual aspirations, a concern with ideas and their transmissions and, not to anyone's surprise, a marvelous technical command. The selector, Jens-Rudiger Lorinzen (with others, notably Paul Derrez and, one assumes, Fritz Falk), has done a much better job on the whole in a difficult situation - there are so many jewellers in West Germany and all the artists one would expect to see were present. Indeed, they deserve an entire review by themselves and I regret that space does not permit such justice.

One significant aspect of the German installation that does bear comment was the use of excellent accompanying photographs, photographs, however, that in many cases gave truth to the observation that much contemporary jewellery is superb in a manipulated circumstance of interaction between model, piece and camera but often much less successful as an object for sustained gallery contemplation, let alone as a wearable.

Much more can be written about this exhibition. In a recent issue of Crafts magazine, Paul Derez wrote, rather contentiously, in regard to the exhibition, "Great Britain produced highly innovative work during the 1970's, which was stimulating and trend-setting, but now it looks as if ten years of Thatcherism have drained the red blood and left imagination faint as far as jewellery is concerned, Dreams are suppressed by realities, or by the forces of commerce or prestige. Communal panache bows out, leaving the stage to the dull or the egotistical."

Is this a true picture of British jewellery today? Is there any evidence to contradict this view? (I think there is.) Have the scope and parameters of the jewellery discussion merely changed to another track, or have they been extinguished? I wish we had been given the opportunity to find out. We weren't.

James Evans is Principal Lecturer and Course Leader for the Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics course in the Department of Textiles and Three-Dimensional Design at Brigham Polytechnic in England.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.