Bruce Metcalf: Between Darkness and Light

5 Minute Read

Bruce Metcalf's recent exhibition Between Darkness and Light thematically embraces and continues his ongoing concern with an anguished sensibility wedged between disenchantment and hope. Immediately striking is his pervasive use of sociological, political and psychological topics. The implications and intentions behind Metcalf's jewelry are explored here by C.E. Licka.

Can jewelry be an effective agent in addressing today's social, political and psychological problems? From the standpoint of using jewelry as a critically charged space, Bruce Metcalf's tableaux all seem to derive from a need for emotional catharsis due to the possibility of nuclear annihilation, alienation, the plight of the consumer and the emotional upheaval and pressures of our postindustrial age. Each of his works is anecdotal, a highly compressed vignette with stylized characters, who vent the anxieties of "everyman" and "everywoman."

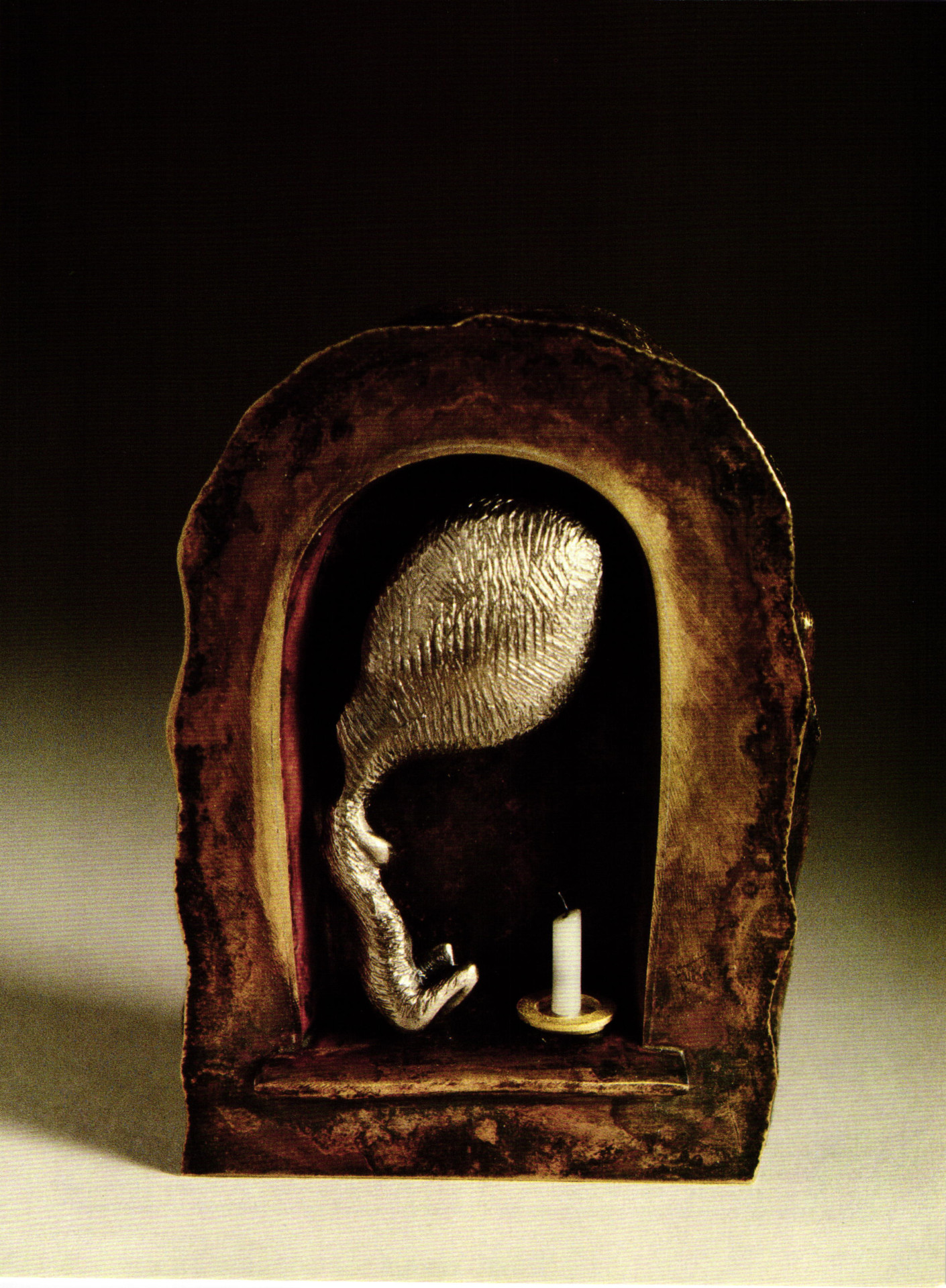

For example, in his brooch Crushed, there is a grimacing figure with a distended neck, leguminous head, ovoid eyes, truncated torso and atrophied limbs pressed between two pieces of black pumice. These elements are set against a softly textured, gray-and-orange field drawn on mylar. The gray zone of the drawing, with its repetitive spongelike pattern, subtly echos the porous surface of the volcanic rock. The figure is being crushed between the viselike grip of the rocks, reflecting one of Metcalf's major concerns over the years - emotional pain and alienation. Niche with Figure incorporates a figure that wraps itself up in its own desolation and in Mr. J. Speaks the figure is imprisoned in bars. Even Mr. J's symbolic utterance streaming from his mouth in a cartoon balloon contains the image of a cage reinforcing the nightmarish world of psychic entrapment.

Metcalf has consistently tried to "touch" the public by creating jewelry and miniature sculpture illustrative of contemporary life. He views his pins "as documents or editorial cartoons in the manner of Daumier and Walt Kelly." Seen from this perspective, Metcalf's sensibility and style has a great deal to do with the tradition of caricature. By deforming and exaggerating the characteristics of the human figure, his voice is one of skepticism, aggressively attacking social injustices, political ideologies and current social mores. As a liberating process, caricature allows Metcalf to get beneath the skin of reality and expose the absurdity of the human condition.

Metcalf's figurative style has evolved over the years into a complex family of forms. For example, the hydrocephalic heads and vestigial limbs are quite different from his attenuated and angular, sticklike bodies. His figures change, but the way he renders them remains consistent. They are always stripped down to their rudimentary functions and emotions, with a linear economy, executed in the precise manner of an illustrator.

His earlier brooches called Hammerhead with 2 Bombs and Catching the Bomb I & II ,like his recent piece, Niche with Figure, are reminiscent of the allegorical cartoons favored by Bosch, Bracelli, Petitot, Grandville and Vertbleu, where they substitute recognizable objects for heads or other body parts. Vertbleu satirized the jury of the Salon of 1840 as being "stupid" or "headless" by replacing their heads with an upended jug, a loaf of bread and a knife, or a violin. In comparison, Metcalf's bomb-headed figure, trying to catch a bomb, is just as absurd and "headless" in its attempt to capture the seeds of its own destruction. Allegory, like caricature, gives us "types" for the express purpose of conveying universal ideas. This is the world of John and Jane Doe, the "everyman" and "everywoman" viewers can identify with.

Metcalf adapts the comic-strip balloon as a way to frame or provide a cartouche around the space of his jewelry, forming an "allegorial ornament." In other words, he uses fragmented visual units within a circumscribed whole so as to produce a literal discontinuity. An example of this from history might be Lorenzo Monaco's late 14th-century Pieta, which portrays a crucifix, decapitated saint's heads, portions of arms and hands and a host of Christian symbols floating above Christ. In our century, Peter Blume's painting, Elemosina (1933) depicts Christ seated with a series of objects, such as watches, flowers in a vase, hearts and jewelry, orbiting around him.

In a similar fashion, Metcalf's brooch, Consumer's Hell, depicts a seated "everyman," isolated and with his hands on his head in apparent despair. Circling around him are ladders and mechanical contrivances. In A Present from the Government, our allegorical hero cringes in fear as bundles of missles float overhead.

Headful of Bad Ideas consists of an inflated head framed by forged-wire balloons with soldered AK-47s and semiautomatic rifles. Headlock depicts a female figure with her head tightly wrapped with a band and secured by a lock. The references to pain are incisively illustrated as the interior world of infinite migraines. Surrounding this figure is a constellation of keys and entangling wires. These "dream keys" seem to offer a way to unlock and break the oppressive band of some uncontrollable force. But, ironically, there appears to be no way out of this psychic impasse.

To a certain extent, Metcalf's jewelry does reach out and touch his audience with a sensitive and emotional form of visual journalese. These are "readable" universal messages filtered through an anguished psyche. One of the risks he has taken is to embrace caricature and allegorical ornament in a discipline that is far from adversarial. There is no question about Metcalf's need to expose his spleen and engender emotions in the viewer. These emotions may be amorphous and difficult to pinpoint, but he does seem to voice the "angst" of "everyman" and "everywoman." In looking at these caricatures and allegories mirroring our world, one enters the universe of this jester's caprices where the "sleep of reason produces monsters" and where we all can momentarily wear the motley.

Bruce Metcalf's jewelry was recently shown at the CDK Gallery in New York.

C.E. Licka teaches art history at Southeastern Massachusetts University in New Bedford.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.