Charles Loloma: Spirit of the New

8 Minute Read

On January 7, 1921, a son was born to Rex of the Sand and Tobacco Clan and Rachael Loloma of the Badger Clan, Hotevilla, Arizona. Rex was an accomplished weaver and respected moccasin maker; Rachael, an excellent basket maker. The family lived in the most traditional Hopi village. Over the years they were able to instill in their son Charles a sense of design, dedication and perfection in the Hopi way - art is not different than daily life. While it is not surprising that Charles Loloma became one of the outstanding American Indian jewelers of our time, the road he followed was uncharted and the resulting work unique. A man of two worlds, he spent time with Oleg Cassini, Marcel Marceau and other international notables, as well as being a member of the Snake Society: he participated in traditional ceremonial life and performed as a clown kachina.

Charles attended day school in the Village of Hotevilla, where his talent was soon recognized by his teachers. Although there were no formal art classes, he was encouraged to draw and paint. He studied art under Fred Kabotic at the Hopi High School in Oraibi, and during this time he was painting murals. He transferred to the Phoenix Indian School and studied with Lloyd Kiva New, and then went on to summer school in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he studied under Olaf Nordmark, a muralist.

In 1939 he received his first major commission, murals for the federal building on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay as part of the Golden Gate International Exposition. In 1940 he assisted Fred Kabotie in painting reproductions of the Awatovi murals at the Haskell Institute, Kansas, which were eventually moved to New York to be included in "Indian Art of the United States." an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1941. These murals are now on display at the art museum in Denver.

Charles finished high school in 1941, and, by that time, he was an accomplished artist, receiving many commissions. He had also illustrated Edward Kennard's book, Hopihoya.

Like many others, in 1941 Loloma was drafted into the army, a first for American Indians. He was a camouflage expert in Missouri, then spent years in the Aleutians as an engineer. In 1942 he married Otellie Pasivaya and, after being discharged in 1945, they returned to her village of Shipaulovi on Second Mesa. With the help of the GI Bill, Charles and Otellie attended the School for American Craftsmen at Alfred University in New York, where he studied design, mechanical drawing, ceramic chemistry and marketing. The university was known for its ceramic program. For Charles, a Hopi, it was unusual to study ceramics, as ceramic art was traditionally a women's craft. Loloma applied for a Whitney Foundation Fellowship to study the clays of the Hopi area. In 1949, while still at Alfred, he proved through his experiments what he thought to be true, that the shale clays would turn to glaze if fired at high temperatures. During his stay at Alfred he also discovered that he wanted to pursue a career as an artist, which previously he had not considered to be a plausible occupation, even though he had been successful in selling his ceramic ware. After completing his two-year Whitney Foundation Fellowship, he and his wife set up a shop in the Kiva Craft Center in Scottsdale, Arizona. After several years he says he simply decided to make jewelry, perhaps because in pottery, once started, had to be completed, while in jewelry he could set a piece aside to work on another and then return to the first piece; it was more manageable.

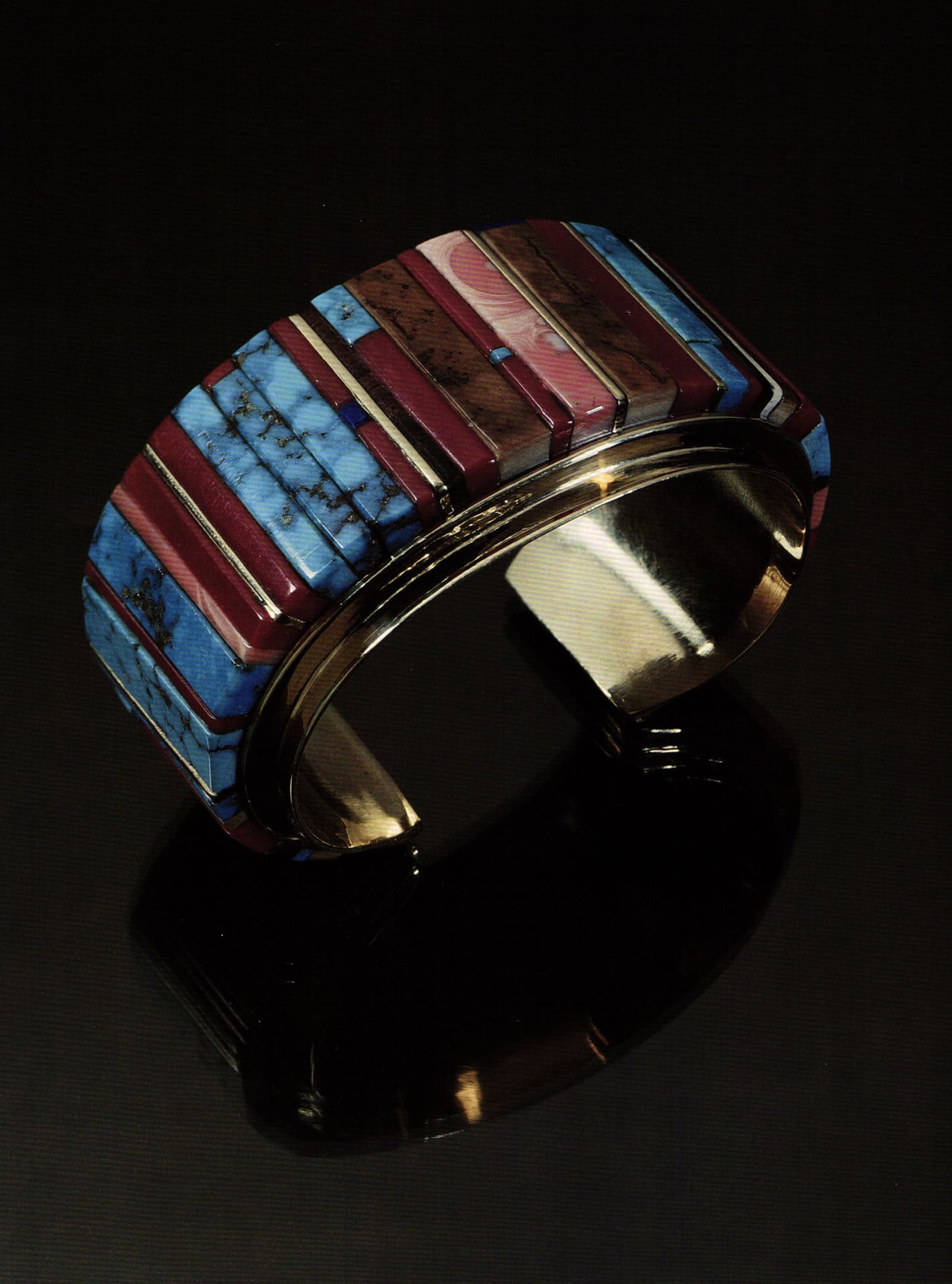

By the time Charles reached age 40, he was well acquainted with many different media. He was self-taught in silversmithing, with the help of John Adait's book, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. His early pieces were cast and designed in typical Hopi fashion - he still wears one of his first ring designs, a badger paw cast in gold - but his creative talent soon carried him be-yond conventional Indian jewelry. After some time, he began to take advantage of unexpected imperfections and to incorporate these into his designs. His painting background enabled him to take various colored stones and blend them together with exceedingly pleasing results. Early in his career as a jeweler, lacking financial aid, the asked his customers to bring him their old jewelry and let him redesign it.

In 1956 he and his wife were running a pottery shop and teaching part-time at Arizona State College, as well as in Sedona during the summer months. This gave him the opportunity both to formulate his ideas on design and to gather experience at selling. Loloma and his wife were two of the first Indians to run a successful pottery shop, and as a result received a great deal of publicity, which of course helped their business.

Loloma feels that good salesmanship, learning to talk to people is a very important factor and he has worked hard to overcome his shyness. His experience in classroom teaching also helped him become a spokesman for contemporary American Indian artists. During the 1950s and 1960s he helped break down barriers that had kept Indian artists and Indian art from mainstream art. Early on, his work was rejected from the Gallup Ceremonial Exhibits as not being Indian. But by the 60s this began to change, and Loloma and a few others were accepted as legitimate. Loloma was the pioneer in jewelry. In 1962 the Institute of American Indian Arts was founded, and Loloma was hired and appointed head of the plastic arts and sales departments In 1963 he traveled to Paris with letters of introduction to the fashion world.

During his stay in Paris, his jewelry was modeled in fashion shows and private solo exhibitions. For him, this trip helped define some new designs. After he left Paris, he returned to the Institute in Santa Fe, where he remained until 1965 when he returned to his village in Hotevilla. Shortly thereafter, he divorced his first wife, remarried and built a studio and home. At this time his jewelry was winning first prizes in Indian art shows and being exhibited internationally. By the 1970s, the Queen of Denmark and wife of Philippine president Marcos had received gifts of his jewelry from President Johnson. He wanted to know what it felt like to own an airplane, to drive expensive cars, to wear a tuxedo, to eat at the 21 Club in New York - the night he did eat there he showed up tieless; of course, the necklace he had on was worth thousands of dollars but they gave him a dollar tic to put on. In 1972 Loloma was featured in the NET film Three Indians, as well as in the PBS film Loloma. He was also appointed to the Arizona commission on the arts and named "Arizona's Living Indian Treasure."

A recent conversation with Charles's wife Georgia helped clarify some of the personal aspects of his approach to Hopi jewelry design.

Can you explain the difference between the Hopi overlay and Charles's style?

Charles started constructing pieces and also did lost wax casting. For many years most Hopi jewelers were doing the overlay using traditional patterns and pottery design. Charles was an innovator; he was never locked into one interpretation.

Does his jewelry represent any particular Indian lore?

I think that with the Hopi Indian and probably with most Indians, that their artwork is not separate from their whole belief system, and that you will see the influences of the music, of the ceremony, of their whole way of life somehow reflected in the artwork itself. Everything that they do is integrated, it's all one pattern. There's not a separateness. You don't go off to do art - you are art.

The ring you are wearing is unusual in that there are hidden stones; does this have any significance?

Yes. It has been a very important contribution. Charles calls these "inner gems" and they represent the collective personal beauty, the value system, the choices that we make as individuals about who we become, that is your inner beauty, it's your inner gems.

Being a jeweler myself I've always been taught that the back of something or the inside, should be as beautiful as the font. Obviously, Charles has carried this a step further, indicating an inner soul light.

It's very popular with rings, especially wedding rings, because people feel not only that they have that inner beauty, the lining of the ring, but, if they had marching rings, or they attached significance to the stones that were used there, that they had an inner covenant that was not seen by the outside world.

I see in some of his work he uses gold as well as silver. Does this have any significance? Because I think, truthfully, Hopi jewelry is primarily silver.

The Hopi's background in jewelry wasn't very extensive as in some cultures, but they started by using Hopi overlay: they used silver primarily. I read an article once that said that in Hopi jewelry there's the Hopi overlay and then there's Charles Loloma. Those two things, Charles started out in silver; it was a matter of economic necessity. And as he began to be able to work with gold, he started incorporating gold. He also had an attitude that if he was making a silver bracelet, and the stone needed the warmth of gold, he would put a gold bezel around the stone. It would simply warm up that whole piece. He also felt that there was no problem incorporating both the silver and gold at the same time, and he was able to pull that off successfully.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Only that as a result of an automobile accident in 1986 the studio is closed and Charles is no longer producing any jewelry.

Phil and Anita London are jewelry collectors, lecturers and writers. Phil is a jeweler and founder of the Pennsylvania Society of Goldsmiths and the Florida Society of Goldsmiths.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.