Claus Bury Architectonic Propositions

14 Minute Read

Claus Bury's rejection of his immediate past, a long standing European tradition in goldsmithing, and his defection to the fine arts by the end of the 70's, points out a major weakness in the crafts: its inability to accommodate radical ideas and shifts of sensibility within its own framework.

Historically, since the mid-19th century, the fine arts community has been associated with the notion of the avant-garde - an antagonistic force dedicated to upsetting ossified academic conventions, pursuing messianic visions of the world and rejecting the normative values of the public.

Whether or not the avant-garde is dead or alive today is a moot point, but when we turn to the crafts, the avant-garde as an internal agent of change and criticism has been conspicuously missing. There are no Salons des Réfusés, aggressive manifestos demanding the past be exorcised from the present nor banners protesting the old order. Lacking such a revolutionary mechanism seems to impede the full participation of the crafts in modern art's polemical tradition. For those artisans whose ideas have outstripped the limitations of their craft heritage, there is no alternative but to cease making art or seek asylum elsewhere.

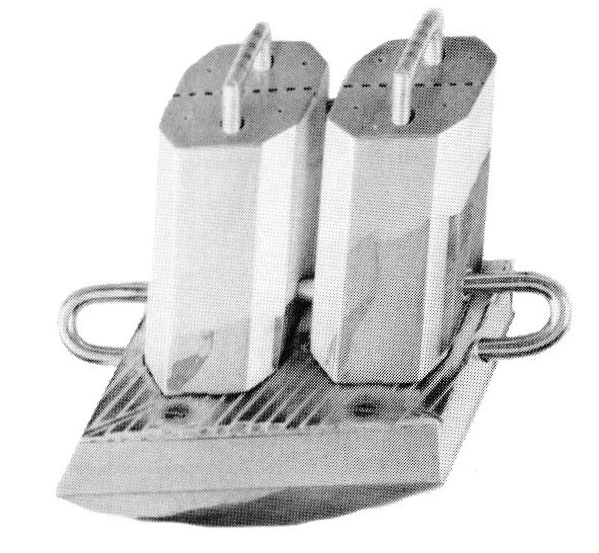

Container Series, Brooch, 1974, Gold 750, Silver 1000, copper, alloys

For Bury and other craft-trained artists (e.g., Peter Voulkos, David Smith, Julio Gonzalez, Gary Griffin), the crafts can be viewed as a stage in their development, a springboard for pursuing other artistic activities. There is no better example of this phenomenon in the history of metals than the relationship of goldsmithing to the fine arts during the Renaissance. One only has to think of Cellini and his progress from an artisan to a successful "fine artist." As a matter of fact, when one reads Vasari's Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, an impressive list of artists can be cited who began their professional careers as apprentices under a master goldsmith: Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Verrocchio and Botticelli.

Bury, of course, did not begin his career as an apprentice under a master goldsmith, but he was thoroughly trained within the European goldsmithing tradition. After his graduation in 1968 from the Kunst und Werkschule, Pforzheim, West Germany, he traveled throughout the world teaching, exhibiting and lecturing. During the early 70s he began to question his traditional jewelry heritage as well as the conceptual and material direction he wanted to pursue.

Black Sculpture, 1979 Photo: Ingrid Kellenbach

- From a conceptual point of view, he partially eliminated the passive role the consumer played in using and wearing jewelry. By setting up a dialogue with the consumer by means of explanatory drawings, or scenarios for activating the jewelry, he gives the buyer of one of his pieces of jewelry a variety of options with which to create his own combinations. A brooch or a ring, for instance, can be worn in multiple ways, or simply become an objet d'art along with the drawing.

There is obviously an element of chance intrinsic to these works, but it is a form of "controlled or designed chance." Behind this game-like guise are manipulative and rational concepts of Bury the designer at work. Controlled chance in this case is at the opposite end of the spectrum of Duchamp's "canned chance," or Jean Arp's spontaneous gestures.

"What distinguishes our modernity from that of other ages is not our cult of the new and surprising, important though it is, but the fact that is a rejection of the immediate past, an interruption of continuity.." Octavio Paz, Children of the Mire

These early drawings for his "participatory" jewelry are analogous to meticulously rendered blueprints. They illustrate the first stages of his kinship with architectonic relationships and the processes by which one can construct structures. Eventually, large-scale orthographic projections are used with provisional sketches to facilitate an understanding of his ideas. These drawings represent one facet of the image of Bury, the artist-engineer, who has continuously emphasized process, whether it was an early brooch with exposed screws, the Concave-Convex Construction (1981) with its meticulous diagrammatic references, or his recent Bridge Project with its body-space manipulations.

Rectangle, Brooch, 1977 Gold 760 H, Silver 935, copper alloys, 6×6 cm, Collection Mr. and Mrs. Willhelm Kraemar

Bury experimented with a variety of different substances in his jewelry. During the early 70's he contrasted synthetics, such as colored acrylics and laminated sheets of Plexiglas, with gold and silver, creating marvelous miniature geometric and perspective rendered illusionistic worlds. But these were imaginative landscapes, abstract glyptic tracings of his psyche. Later on, during his stay in Jerusalem from 1975-76, he initiated explorations in "real" space and its implications for site-specific works. But up to 1976 he was still incorporating and experimenting with the use of metallic alloys in his jewelry. He felt, however, that the random effects of the color combinations achieved through a trial-and-error process should be systematized in some way. This led to metallurgical experiments at the Degussa Factory in Hanau, West Germany in 1976. These color studies in metals are comparable in their rigor to Klee's magic square pictures of the 20's that focused on a variety of color relationships (e.g., Architecture of Planes and Intensification of Color from the Static to the Dynamic both from 1923).

Like Klee, Bury was, and still is, concerned with the underlying structure of nature, its proportions and mathematical systems. The Degussa experiments, in light of their analytical nature, were akin to a personal pedagogical primer for Bury. It was from these experiments that he obtained a more stable range of colored metal alloys to investigate surface effects and reflective properties. This research, combined with his new interest in site-specific notions, proved to be the catalyst for his last series of jewelry between 1976-78.

Diagonal 1, Brooch, 1977 Gold 750, silver 935, copper alloys, 6 x 6 cm, Collection: Schmurckmuseum Pforzheim, West Germany

Bury's innovations as a metalsmith had earned him an international reputation by 1975. Success appeared to be a fait accompli. But this was also a year of critical transition for him. He began to take risks outside of the metalsmithing framework. As a guest teacher at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem between 1975-76, he investigated the complexities of site-specific works in the Judaen Desert. Instead of continuing to construct the illusionistic geometric forms of his brooches, he surveyed real space by siting procedures and choreographed the movements of his students on the desert terrain in works such as his Geometric Formations, Part I (1975). This territorial assertiveness was a logical outcome of his dissatisfaction with metaphorical space in jewelry, and points to a topographical consciousness reminiscent of Le Corbusier's remark about the origins of man's spatial consciousness: "To take possession of space is the first gesture of the living, men and beasts, plants and clouds, the fundamental manifestation of equilibrium and permanence. The first proof of existence is to occupy space."

Geometrical Formations 1 Judean Desert, Israel, 1975

These initial experiments in the desert not only set the stage for Bury's later architectonic works, but also indicated his affinity with earlier 20thcentury developments such as Russian Constructivism and the Bauhaus. His use of Plexiglas and polyethylene, the use of elemental means of expression and a belief in the fusion of art and life are expressive of the constructivist tradition, but it is critical to keep in mind that Bury's work doesn't reflect the collective outlook of that generation's "artist-engineers." Gabo's "constructive realism" of the 20s, which argued for the independent status of art and artist, is closer in temperament to Bury, as is Gabo's belief that one should create constructed images "that are a factual force" making "their impact on our senses . . . real as the impact of light or of an electrical shock. . . ."3

Factual forces or experiential structures are manifested in both his movable and interior/exterior static works. Resonating throughout these pieces is the desire to reinstate and accentuate the spectator's sensory experiences and relationships to man-made and natural surroundings. Movable sculptures, like his ongoing Geometrical Formation Series Parts 1-6(1975-82),are reminiscent of Oscar Schlemmer's Bauhaus stage productions - Dance of Slats or Dance in Space (1928-29). The use of elemental formal relationships, and the idea of manipulating space with a variety of simple props as if it was a viscous transparent medium, is shared by both artists.

Geometrical Formations 3, 1978 45 participants, White cotton, Sinai Desert. Photo: Miriam Sharlin

For example, in Bury's Geometrical Formations Part 5 (Offenbach, Germany, 1981), six students are lined up behind one another with their legs spread out on diverging train tracks, creating an inverted Y-shaped configuration. Each student holds a vertical stick directly centered in front of him and approximately two feet higher than his head. A string is wrapped around each stick and then tied to the rails of additional outer tracks. A formal equivalent between the inverted Y-shape of the torso/spread legs and the vertical stick/string is created at one level of perception. The height at which the string is attached to each stick also varies. The string extends from each side of the stick like a web line and is secured to the sides of the outer track. By progressively raising its height on each receding stick in a serial manner, Bury has created an arithmetical sequence that suggests an underlying structural system. Geometry, tension, perception and the body as a structural coordinate are integrated into spatial experience in which each participant senses his own physical relationship to that space.

Geometrical Formations 5, 1981 Offenbach, West Germany. Photo: Claus Bury

Other less apparent influences on Bury's movable sculpture can be traced to the performance-oriented works of Klaus Rinke's "actions" and "demonstrations" (e.g., Interpersonal Relationships and Primary Demonstrations Along the Wall and Franz Erhard Walther's Handlungen (activities like his Exercise First Set No. 58 and Primary Relation Form-Rest Form). These works all referred to a variety of phenomenological inquiries using minimal gestures, presentations, sequential systems and simple activities which allowed the artist to manipulate people, objects or himself. The purpose behind these "activities" was to experiment with and create new relationships and experiential possibilities within a specific setting.

This experiential feature is a constant in Bury's art. His Black Sculpture (1979), Wind Sculpture and, Extension Installation (1980), Raumvershiebung (Spatial Displacement, 1981), and his most recent static structures, Two Elevated Walkways (1982) and the Bridge Project (1983), set up in Madison Square Park, must be seen against the backdrop of previous earthworks, systemically associated sculpture and minimal developments of the 60s. Closer in intent however, are Post-Modern artists like Robert Irwin, Bruce Naumann, Michael Asher, Massimo Scolari and Alice Aycock who fabricate architectural environments that emphasize the physical and psychological dimensions of experience. Their ideas, like Bury's, indicate a predisposition towards architectural notions concerning time-space relationships and the ordering of that space. However, it is not only the visual aspect that interests Bury and these artists, but the intensification of our senses by other means, such as touch, sound or movement. As a result, human interaction and scale are crucial to these works. Seen in this light, Bury's experiential chambers are like sieves, what Merleau-Ponty has called a "porous" reality.4 It is this porosity that manifests itself as one moves in and around his spatial worlds.

Concave-Convex Construction, installation at List Art Center, Brown University, Providence, RI, January-April 1981, Wood, 15'2″ x 17'6″ x 38'5″. Photo: Jonathan Sharlin

All of Bury's site-specific undertakings have been temporary structures, and an installation like his Wave Sculpture (1979) expressed the dialectical and process-oriented nature of his thoughts. In this case, he opposed a passive manmade structure against the active ebb and flow of the waves. The sculpture, placed on the beach, consisted of wood, twine and translucent cotton sheets that rippled like sails in the light. Seen from the side, it suggests an ascending series of abstract louvered wave sections cascading down the backside. As the waves gradually pummeled it the structure fell apart. This process of disintegration by natural forces has a quality of the sublime and registers a sensitive metaphor for the flotsam of experience and the temporal nature of manmade structures. Even though there are entropic overtones in operation, they are not of the magnitude of Smithson's large-scale displacements. Instead, the event is on a human scale directly experiential. One is in the present witnessing and experiencing the clash of two different creative forces, rather than Robert Smithson's geological sense of time and the erosive processes of nature, which are gradual and beyond the present.

Two Elevated Walkways, Installation at Moore College of Art, Philadelphia, PA, wood, 1982. Photo: Jonathan Sharlin

His most recent ventures, Two Elevated Walkways and the Bridge Project, expand upon his architectural and experiential premises. Walkways was an interior installation consisting of two parallel, alternating, tunnel like chambers, gracefully undulating like two overlapping sine curves on a graph. By ingeniously revising the previous architectural setting to accommodate the space as he envisioned it, Bury set up a wide range of experiences for the spectator. One has three options for entering the two enclosures, and once inside, there are a variety of views between the walkways as well as out into the gallery. Light and shadows move through the space of the interior as if it were a static space-light modulator. One isn't pressed through this space as in the later Bridge Project, but there is a tendency to coordinate one's movement through the space to the rise and fall of the wavelike corridors. From the outside the structural arrangement reads as if it were an infinite mathematical progression that could continue beyond the confines of the gallery.

Oscar Schlemmer, Dance of Slats, 1927. Photo: Bauhaus Archives, Berlin

The Bridge Project, constructed during the Brooklyn Bridge Centennial at Madison Square Park, is Bury's latest, and one of his most interesting works. This is the first site-specific project to be fabricated within a large American metropolitan area. Approaching it from a distance, one immediately responds to the iconic presence of this structure set within the bowered atmosphere of the park. Two l2-foot high wooden pyramidal shapes face one another with a centralized tiered section flowing down the base of each section. This inclined triangular shape is a recurrent form that has intrigued Bury since his first sitings in Israel, and in this piece, variations on triangular shapes play an important role. The triangular sheet metal element that spans the two pyramids not only reflects the Brooklyn Bridge in a symbolic manner, but the references to the surrounding architectural structures-the Flatiron Building with its narrow wedge-shaped iron facade and the Mutual Life Insurance Building with its ascending terraced stories capped with a pyramidal shape - conjure up other formal connections and building processes.

| Wave Sculpture Construction and Destruction within l8 hours Installation at Palm Beach, Sydney, Australia, May 1979 Pine, white cotton, twine. 8'2″ x24'6″ x 393″ | |

The analogy to modular construction techniques and the serial window facades of the buildings that skirt the periphery of the park reinforces the systemic arrangement of this piece. However, the underlying mathematical system might not be apparent at first glance. He bases the proportions on Fibonacci's numerical system and his own body proportions, resulting in a vertical height twice that of a six-foot man. The use of mathematical systems only reflects the rational or apollonian elements in this work. Bury thinks dialectically, and it would be misleading to emphasize the analytical aspects of his work at the expense of its Dionysian counterpart-the emotional and irrational responses of the artist to his world.

By manipulating the individual's relationship to space the Bridge Project reflects a variety of psychological and physical responses. For example, the lowest tier, constituting the inside wall, frames the passageway so that only one person at a time can pass through. One gets the feeling of being squeezed between two massive forms and then released into an expanse of space. By intensifying a general sensation one has about New York-the sense of compression created by the solid masses of buildings-Bury momentarily internalizes the idea of tension both physically and mentally. Since movement is constricted by the width of the passageway, one operates like an element within the structure, a kind of human bridge or structural component that links the two forms at the base. The body becomes the "fabric into which all objects are woven . . . that strange object which uses its own parts as a general system of symbols for the world."5

The Bridge Project, like a great many of Bury's other site-specific works, appears to be an attempt to humanize and reactivate urban spaces. It also represents the culmination and continuation of his previous biostructural (body space architecture) investigations and is indicative of his desire to make his architectonic propositions not only a reality but an organic part of our consciousness and perception.

Notes

- Octavio Paz , Children of the Mire, Modern Poetry from Romanticism to the Avant-Garde, trans. Rachel Phillips, Cambridge, MA: Harvard U. Press, 1975, p. 3

- Le Corbusier, The Modular, Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1954, p. 30

- Naum Gabo, "On Construc tive Realism," 1948, from The Tradition of Constructivism, ed. Stephen Bann, NY: Viking,, 1974, p.234

- John F. Bannan, The Philosophy of Merleau-Ponty, NY: Harcourt Brace, 1967, p. 107

- Ibid ., p. 93

C.E. Licka teaches art historv at Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.