Dan and Daniela Imre

10 Minute Read

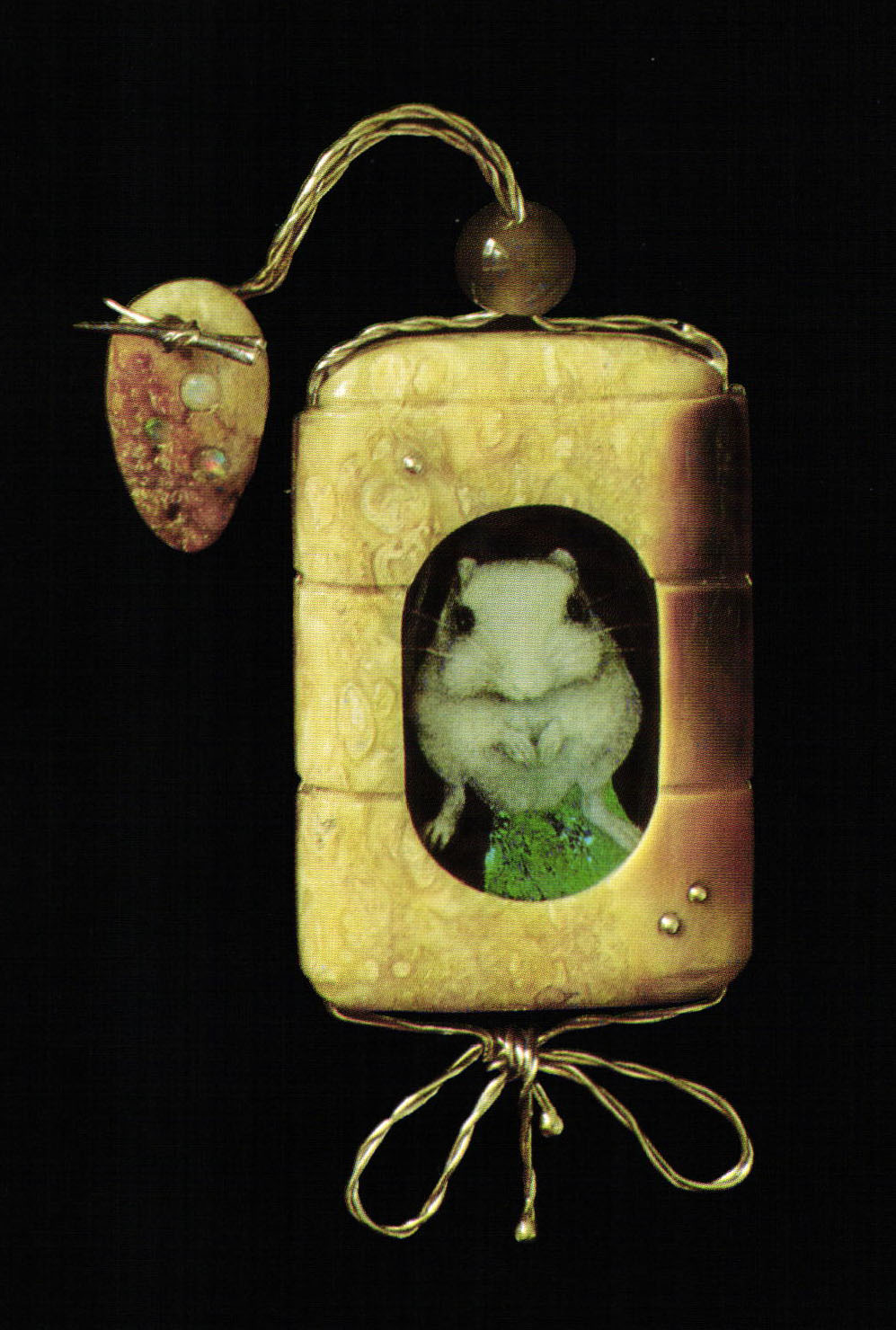

Daniela: The thing about the jewelry is that it's not just a little picture. It's everything that surrounds it and makes it into this thing to wear.

Dan: What I like about it being jewelry as opposed to something on the wall is I like to touch it. It's something that you wear and it's part of you. It's much more personal. The other nice thing about making jewelry is that it has to be wearable. It cannot be huge. It puts some bounds on…

Daniela: not only on the size…

Dan: design.

Daniela: It gives you parameters to work with.

If you have ever wondered how two people can collaborate on a single piece, talking with the jewelers Dan and Daniela Imre clarifies the process. They literally finish each other's sentences just as Dan finishes the brooches, necklaces, and cufflinks that start with an enamel-on-glass jewel by Daniela. At the center of each of their engaging works is a highly detailed grisaille enamel painstakingly created by Daniela. She says, "the jewelry is totally subservient to the image in the enamels".

Those images are haunting: a crouching figure under a layer of crackled glass held together in an embrace outlined in silver wire (Inner Child), a double portrait that becomes a triple when a profile is discerned between the two faces (Family Portrait), a diva performing in a shower. These small enamels framed by abstract shapes go beyond being a beautiful thing to wear. They offer a rich visual experience, but the restraint the Imres exercise in limiting their color to gray scale and the straightforward geometric forms of the soft slate and smooth ivory of the mountings keep these pieces in a cerebral realm. This is also a place of deep feeling and intellectual engagement where they tell their personal stories. Daniela explains that all of their work reflects her mood when they are made, but the directness of form and image allows those who see the works to interpret the stories for themselves.

Daniela remembers one collector calling to confirm their reading of a piece. Inspired by a recent photograph, the enamel with "lots of people with their fists up" was made into a paperweight with a piece of shattered glass on top. "The collector said, 'I know what it is. It's about the Holocaust' and I just stopped and said, 'You could say that. "What am I going to tell her? At first I was taken aback by that, but it's fine. It doesn't matter really as long as somebody has some emotional involvement with it, whatever they see."

Although the Imres' work evokes strong reactions in people, Daniela insists that she takes a very formalist approach. "Maybe they look to someone like they have this deep message in them but often they're just aesthetic decisions", she says. "Why did I put the tree there? Because I wanted to have it there. As long as it does something to you and you find a connection with it for whatever reason you do, I think that's kosher. It's probably what the piece is about. Whoever buys it is going to wear it and it's about something to them. That's the most important thing to me, not what I thought when I did it."

The pair's accomplishments are quite remarkable because they have only been making jewelry since 1989. They did not start out to be jewelers. Daniela was born in Israel in 1951, the same year that Dan moved there from Belgrade at one-year of age. In 1975, after the Arab-Israeli war, they came to the United States. As Daniela explains, "We came like many young people because we wanted to see something else and we never thought we would stay here. We came to go to college".

An American friend said that there were only two places to consider in the US: Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Eugene, Oregon. Although they applied to universities all over the country, the first acceptance they received was from the University of Oregon in Eugene. Since psychology was an interest - they had both taught autistic children in Israel - they began studying that. Eventually Dan was drawn to physical chemistry and Daniela to biology and then architecture. He holds a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from MIT and Daniela a masters in architecture from Harvard. In 1984 Dan's teaching job at the University of Washington took them to Seattle. Daniela worked there as an architect, designing award-winning housing for which she received little acknowledgement. Disillusionment with her chosen profession and the death of both of her parents left her searching for a new focus.

Lenore Kobayashi, a close friend, taught Daniela an enameling technique that had been developed by Seattle artist Lisel Salzer. Now in her late eighties, Salzer had reinvented a grisaille enamel method that she and her physician husband had seen at the Frick. Until about a decade ago, she had been very secretive about it; then she decided that it should not be lost again. She produced a video and book and began to teach a small number of students, including Kobayashi, who, with Salzer's permission, taught Daniela.

Kobayashi took Daniela to a glass fusing class in a stained glass supply shop. In two weekends Daniela learned "… all I know about glass". Kobayashi also pushed Daniela into jewelry.

Daniela: She said I should study jewelry and I went 'naw, naw,' so she paid me to take the class…

Dan:… as a birthday present.

Daniela: I went to Pratt Fine Arts and Dan stayed home. He got very bored being home alone in the evening so he snuck his way into the class. At first he was just sitting there and then the instructor said, "You are here too often. You might as well just pay" so we did.

In two classes, they learned the basics of jewelry-making. In the first class, taught by Charlie Anders, they did a piece that was "a necklace with an enamel of the head of a little boy, angelic. He said, 'Why don't you enter this jewelry show at Facèré?' a jewelry art gallery in Seattle. So we made two more pieces and we got in. After the show was over, Karen Lorene, who owns Facèré, called and said that she would like to represent us and would like to have more pieces." That naturally encouraged them and a new career began for the physical chemist and architect duo.

The Imres' creative and production process follows a definite pattern. For Daniela inspiration comes from anywhere and everywhere. "Everything is kosher as far as I'm concerned to get ideas. I have very eclectic tastes and anything works, a photograph, something I see, a book, it doesn't matter. Sometimes if I'm really hard against the wall, I take the piece of glass and I just daub the stuff on it. I look to see if l see any shape in it. Anything goes." But the process always includes a figure, a suggestion that all of Daniela's enamels could be read as self-portraits. "I'm drawn to figuration. The landscape leaves me cold. Maybe that's why I'm not an architect any more."

The enamel is then done by Daniela on fused layers of glass (clear over a dark background) rather than on the more traditional copper. With semi-opaque Thompson Enamels, she builds up a miniature relief sculpture, the thickness of the enamel grains determining the translucency of the image. Although the resulting enamels can be extremely detailed and highly realistic, Daniela insists that she cannot draw.

Daniela: Painting is not my medium because you cannot correct your mistakes.

Dan: When you paint, you put a line down, that's it. It's there forever. Here you put little grains and you push them…

Daniela: …until it looks the way I want it to look. Here it's as if you never did anything until you put it in the kiln; you haven't committed yourself at all.

Even though enameling would seem to be extremely tedious, working with size ten aught sable brushes, Daniela finds it an extremely satisfying process. "I'm surprised. I'm usually impatient, but with this for some reason I can sit there and I can just pull it through", she muses. "I still don't understand it. I don't even have the patience to sit and take a bath. That's too boring and too much sitting for me, but this, I like."

Once Daniela is satisfied with the enamel, it is fired, often going into the kiln late at night. It comes out, usually the next morning because "by the time it cools off, we are sleeping. We sit at breakfast and we argue a little bit about what it should be like. Less than we used to", laughs Daniela. "Then I do some drawings about what it's going to look like. I've tried many times to design the whole piece, know what I'm going to enamel and know how it's going to be mounted. It never works. It always comes out of the kiln and you look at it and you sit with it and then the mounting comes."

Although Dan insists that his contributions are purely technical, Daniela disagrees, saying, "He's also my sounding board. If I have an idea, I'm not going to start it before I talk with him and we decide that we both like it".

Once the basic design is agreed upon, Dan retires to his basement studio to execute the setting of slate and fossilized ivory with a silver backing. They have always used other materials including concrete and plan to use others in the future. The gray and cream of these materials add a richness to Daniela's favored gray scale. Dan works from Daniela's sketch and then reworks the mounting to accommodate the changes Daniela wants once she's seen her ideas realized. She confesses that "… that's the only place in life where I'm the brain and he isn't". Yet she also readily admits that "he's getting better than me in figuring the three-dimensional quality of it out".

The mountings have an architectonic look about them, which can surely be attributed to Daniela's background in architecture. She recalls her years at Harvard with affection.

Daniela: Harvard was very good. It didn't teach much about architecture. They taught design, design, design. We had people in my class that would present things that were totally…

Dan: … conceptual…

Daniela: … incomprehensible. They couldn't stand up. They were up in the air but if the design principle was coherent, they were great.

Every Imre piece is recognizable because of their faithfulness to the grisaille enameling technique and their handling of the mountings, but they never make editions. Daniela explains, "Once I've done something, I don't want to do it again. It's enough that I keep the technique and then I want to do something else".

Stylistically Daniela has moved from highly realistic renderings and an infatuation with extremely small scale to more stylized figures, reflecting her current interest in art from 1900 to the 1940s, including Art Deco and Russian Constructivism and larger scale. Thematically the earlier obsession with death has been replaced by a vitality inspired by the cultural energy of New York, near where they live as Dan now works as a research scientist at the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island.

One constant in the work remains: the angst Daniela endures as a part of the creative process.

Daniela: [The working process] … is horrible. I have this period of sheer agony when I think it's never going to happen again…

Dan: She calls me every 15 minutes at work. . .

Daniela: I'll never get another idea in my skull.

Dan: I tell her, "Why don't you go be a secretary? I don't care, you know. If you want to stay home, I'll bring you home a salary. Take care of the dogs".

Daniela: Anyway it takes a while of that where I just know it's never going to happen. That lasts for two weeks on average where I just know that I'm dead and that I'm going to be caught and I'm a fraud and this is it and this is the end. And then sometimes, I don't know, happens. And sometimes what happens is extraordinary. You have a feeling and it all works. In architecture school, we had a very famous architect teach a class. He came and said there is this little man in the back of your head when you are working. He looks at your drawing and says, "Yes!"

Karen Chambers is a frequent writer on glass who resides in New York, NY.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.