David Paul Bacharach – Weaving in Metal

5 Minute Read

David Paul Bacharach is a part of the growing contingent of American metalsmiths who are challenging the Modernist tradition of vesselmaking (see "American Holloware, Changing Criteria" by Jamie Bennett, Metalsmith, Summer 1984). He has managed to avoid the principles of functionalism and significant form which have dominated post-World War II holloware by turning to another craft form, basketry, for inspiration.

Fortunately he has gone beyond the gimmickry of merely recreating a vessel that is traditionally, and more successfully, made in another medium. Instead he has used basketry's forms and weaving techniques as a background for virtuoso metalwork.

Although Bacharach has been working in metal for 20 years, it was his refusal to isolate himself within the metalsmithing world which eventually led him to create his woven vessels. As he explains, "l have always spent a great deal of time studying contemporary American crafts and wondering how to incorporate the colors, textures and forms I was seeing in these crafts into my metalwork. Also a student of American Indian baskets and clay, Japanese bamboo baskets and bronzes, and pre-Columbian metal, I have attempted to mesh the forms and images from these ancient sources with those from modern American crafts to yield the body of work I'm now involved with."

Bacharach was attracted to the weaving process primarily because of its spontaneity, a trait that is essential to his method of working. "When I begin a new piece, I do not have a definite idea of what that particular object is going to do. As I progress I determine how each new section will be integrated structurally and visually into the whole," he says. "My initial woven form is held together only by copper tie-wires and is, therefore, fairly unstable. This inherent instability allows me to easily push, stretch and cut the piece: into a shape I'm comfortable with. At this point I take the piece to its first 'finished' state, including brazing all seams, patination and adding gold leaf. After living with the vessel for a while, I section it on the band saw and braze it back together in a new format, many times integrating fresh weaving over the original surface. When the new structure is finished, brazing, patination and gold leafing are repeated. This process will continue until I am satisfied with the final vessel."

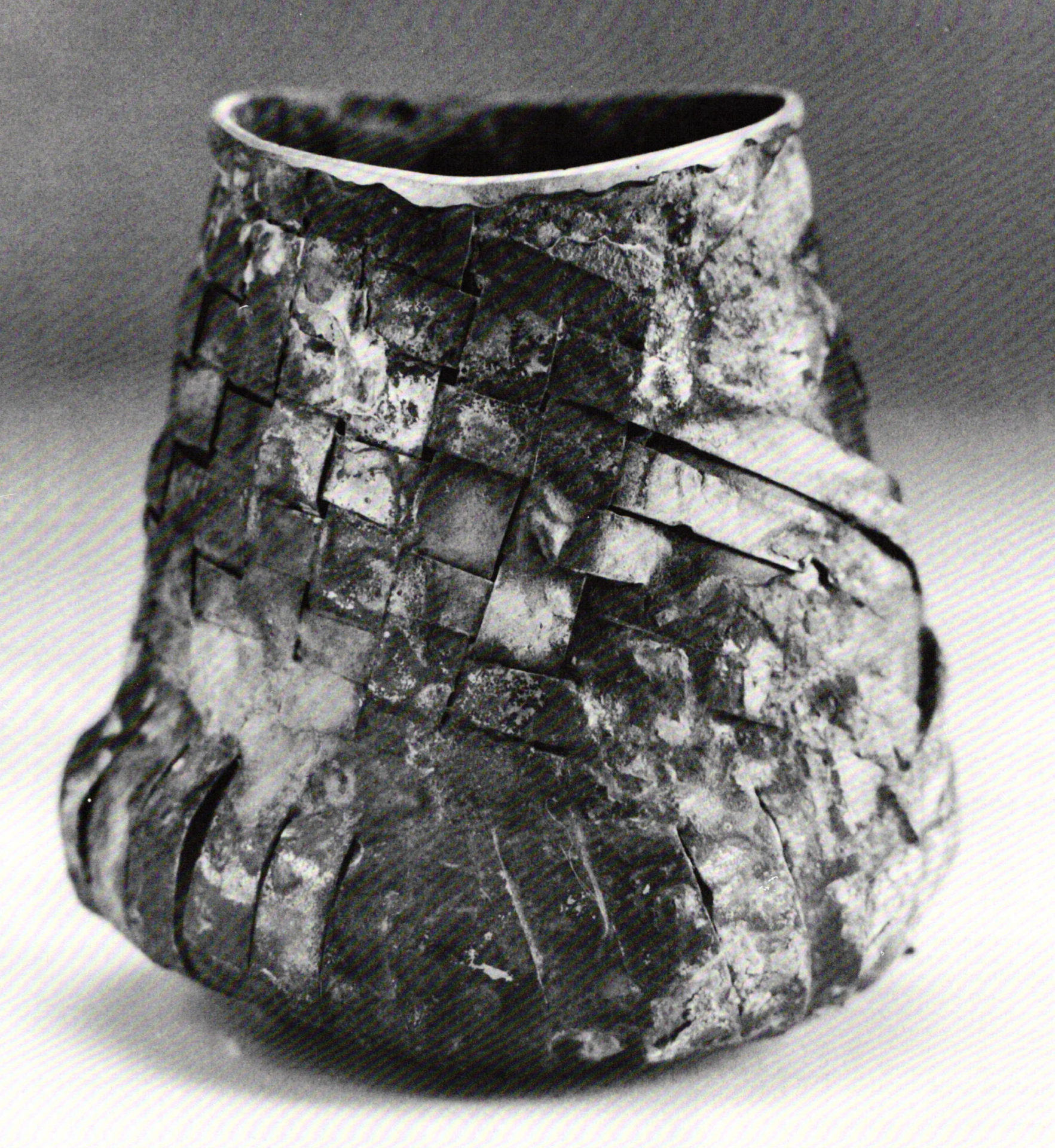

After all this reworking and manipulation it is surprising that in Bacharach's finest pieces his original sense of spontaneity still endures. His small gaming cup is a fine example. Its unpretentious appearance conceals the many hours and rareful planning that went into its creation. The bulging base of this cup, pierced by numerous vertical slits, seems as if it is straining to burst its seams. Above this swelling, Bacharach has incorporated a woven section, slightly skewed, so that the unwoven weft strips at the edges form diagonal lines. These lines continue around the piece, visually forcing the observer to rotate it. On the opposite side the diagonal strips criss-cross over a solid background before recombining into the woven section. The cup's rough texture and heavy patination not only add life to this inert form, but also help to unify it. The brass rim which tops all his vessels, satisfyingly completes the piece.

Bacharach's mastery of patination plays a key role in the effectiveness of his work. Because of his fascination with this form of coloration he limits his materials to copper and bronze alloys. "They have the ability to take on a multitude of patinas, producing countless color variations," he notes. However, patination can be a very serendipitous technique. "By using several different alloys and brazing rods in each piece, I can control the basic color and pattern, but there are always surprises," he says. "I control and vary the coloration with paper and wax maskings, heat and acids. When the weaving and patinas are completed, but before I seal the piece, I may intensify or accent the finished vessel with paint or gold leaf."

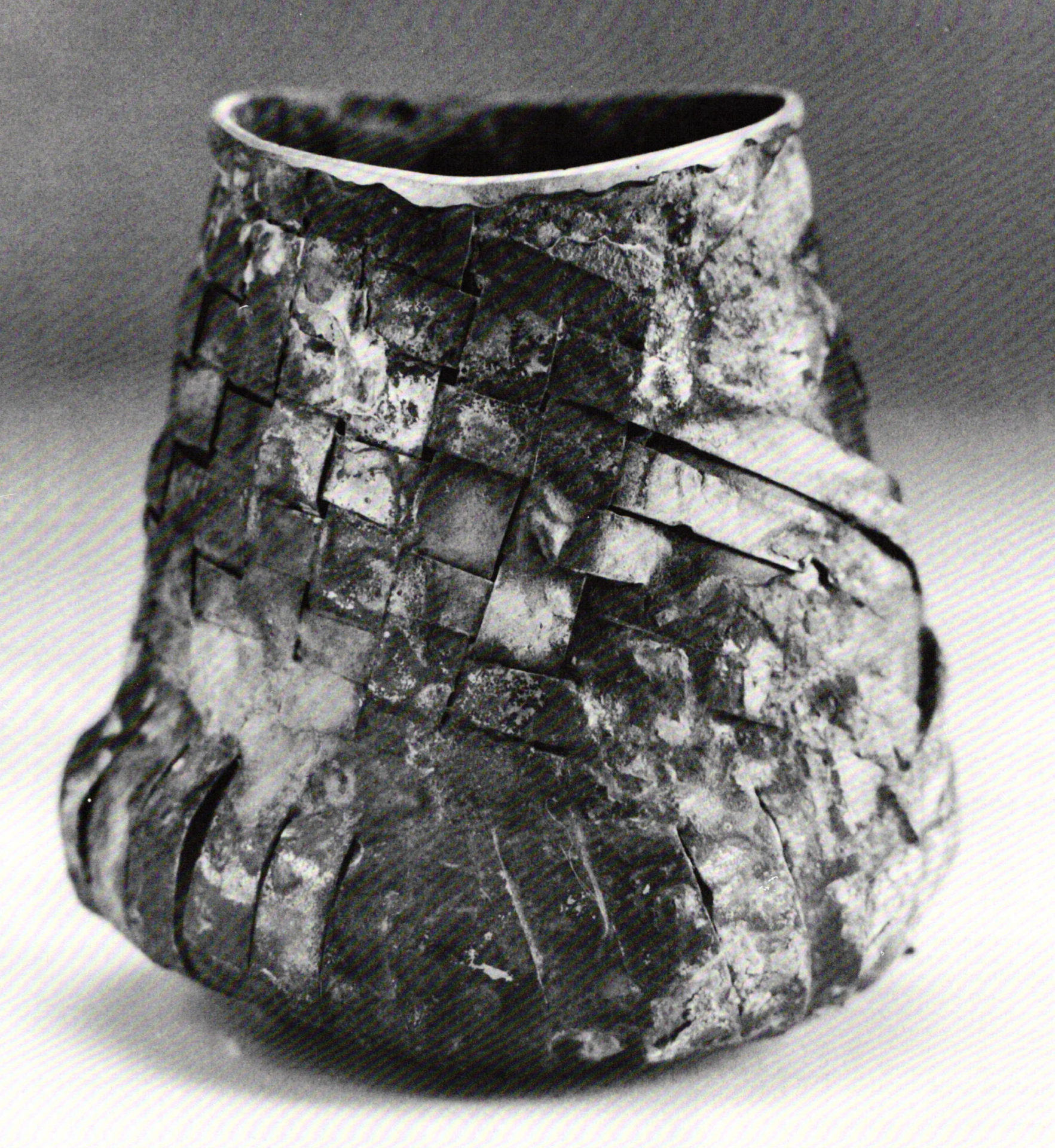

On his large urn, Bacharach's painterly use of patination is somewhat reminiscent of the abstract expressionists' use of stain in painting. On the crumpled and torn copper ribbon which circumnavigates the vessel, he has applied blotches of color that flow onto the woven strips beneath it. In this manner he manages to effectively integrate this added piece into the whole. This ribbon, with its sensitive patination and texture, provides a local point for the urn as well as adding depth to the surface.

In this piece Bacharach uses wide, fuzzy black diagonals, softer and more subtle than in the gaming cup, to lead the viewer around the piece. However, as one turns this vessel the weaving abruptly ends. In its place, against a richly colored red background, are two narrow, almost parallel, horizontal lines of gold leaf bisected by an undulating black line. While both sides are truly handsome, the sudden change in style is somewhat jarring.

Perhaps because Bacharach's work is so dependent on spontaneity, serendipity and subtlety, not all his pieces work equally well. If the patination, texture or form is deficient in any way, his vessels lose their visual strength. But when all the elements come together successfully, the results can be impressive.

Although Bacharach has been weaving metal for five years he is still intrigued by the unexplored possibilities and plans to continue to push his woven forms in new directions. "I am looking now to give the surface of my pieces more depth by broadening my pallet of patinas and by experimenting with other techniques of surface manipulation such as raku and shibori. Additionally, I've begun to use a loom I designed that will allow me to produce complex weaves in metal for architecturally sized vessels and wall panels."

A change in scale will certainly pose new challenges to Bacharach. It is a reflection of his artistic temperament that he is unwilling to rest on his past accomplishments.

David Bacharach's work was shown in a group exhibition at the Craftman's Gallery in Scarsdale, NY in April, and a one-man show was held at Signature Gallery in Boston in October 1984.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Leila Tai – Plique-a-jour Delight

Alberto Alessi

Gold: Here Comes the Sun

Olaf Martens: Masks and Facades

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.