Deborah Aguado: Use of Image and Enigma in Jewelry

8 Minute Read

Stone, metal and space compose the careful balance in Deborah Aguado's work. Her first geometric formalisms constructed in metal were developed in 1973 when she participated in a goldsmithing seminar at the Akademie für Bildende Kunst in Salzburg, Austria. They resulted in a series of two-inch metal squares, called Constructions I, II and III. In retrospect, Aguado sees these as "process pieces." She realized that sketching on paper could not reveal the density, hardness, proportion and the effect of the third dimension that the metal construction would.

Her concerns evolved into the study of perspective: geometry altered by distance, time and space. A perceptualist's interest in the "moon illusion" (when the moon appears to be closer to you when you see the horizon) became a formula for a new series. Railroad tracks are usually used to depict two parallel lines converging and the railroad tracks became the leit motif on which the Night Train series developed.

In 1981, Aguado was asked to develop a program for the American Craft Museum to celebrate its 25th anniversary. As program director of "Craft in Process" and artist in residence in metals that summer, she developed a body of work, primarily the Night Trains. Witnesses in the form of working assistants and observing public and a 10-week time frame provided vital reinforcement.

Besides referring to placement in time and space, the Night Trains can be either a literal railroad iconography or they can depict a grill, cowcatcher, reference to a tunnel or dream railroad yard, where advancing or receding trains have been translated into jewels. A large circular stone suggests a headlight; the markings of an agate refer to a landscape; the vanishing point is suggested by the graduated linear design of a silver trapezoid.

Aguado develops her work on graph paper. This grid system becomes the format for the vanishing-point drawings to which the Night Trains relate. These angles made by the converging lines of the drawing determine the size and proportion of the piece of jewelry and its potential placement on the drawing. The Night Trains are wall pieces when not being worn.

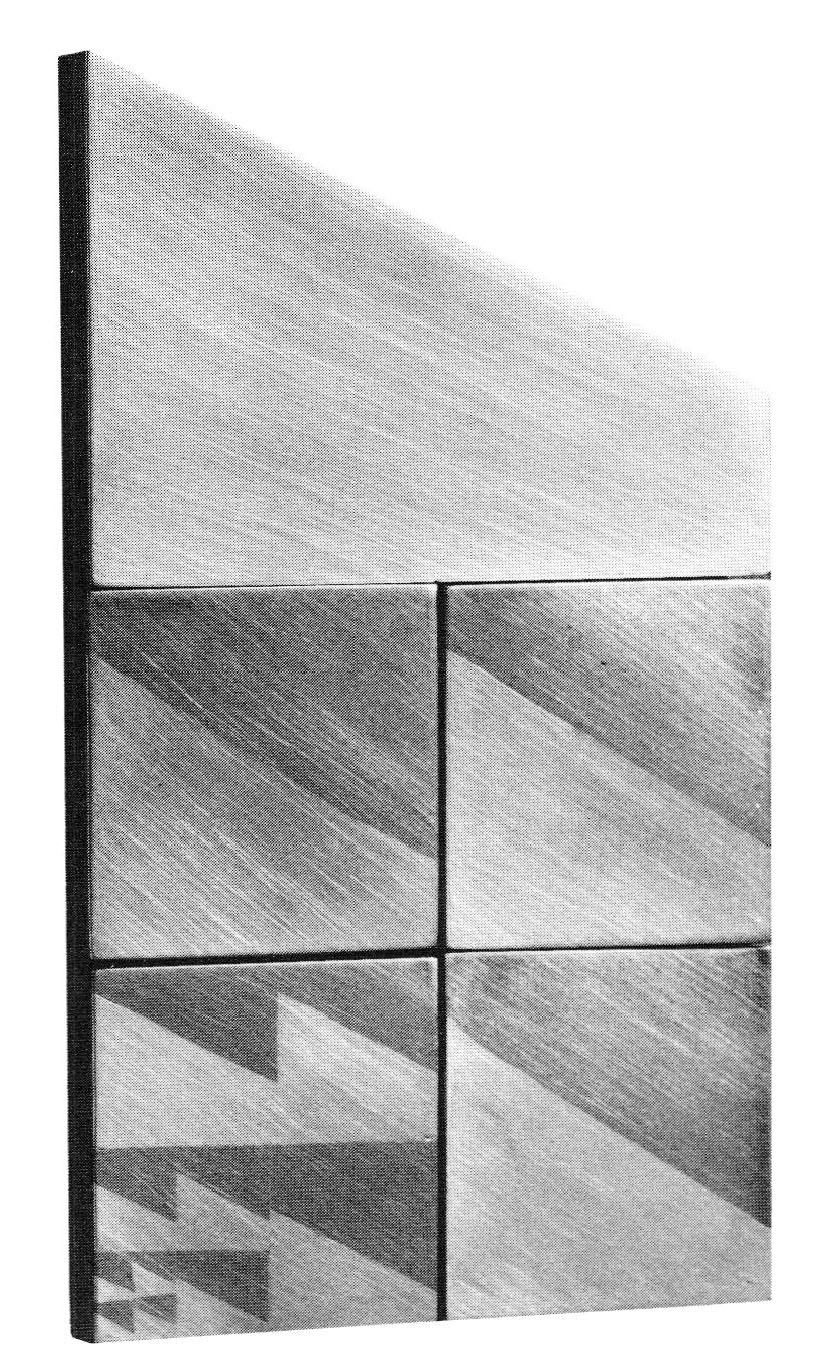

In the Facade series that followed, "a repertoire of the patterned surface" evolved from the graduated and geometric linear elements that had formed the Night Train series. And though more abstract and less illusionistic, this series continues to study the effect of surface pattern and plane. While the Night Trains were explicit illustrations of perspective, what followed are more allusive studies of surface.

The severe linear elements that had suggested landscape in the Night Train series are exploited in the Facade series for their pattern, which when cut apart and repositioned with added dimension affected a new planal integrity. Planes were determined by the various components, Aguado explains "in the way one might apprehend surfaces of the city landscape as affected by light, movement and one's position." The juxtaposed planes and subtle angles are affected by the reflections of light they cast upon one another. They are defined even more, however, by what Aguado calls "viewer position dependency": Assorted planes attract light as the viewer, or wearer, changes position.

Facade III is a further reduction of Facade IL Having the same 18-karat gold triangle and silver stripes as in the earlier piece, this study has been made more luxuriant with the use of gems. Fourteen-karat pink gold, copper, nickel, silver, a pink tourmaline and a green citrine compose a piece richer in color, but one simpler, more reductivist in form. A textured square surface gradates into a triangle, and that to a series of smaller squares and stripes. Facade IV is an even more concise conclusion in its series of reduced triangular planes.

While these inquiries into space, light and distance suggest that these pieces could be models for larger sculptures, one is inclined to agree with Aguado that their current scale is satisfying. She further observes that were these pieces to be translated to a larger scale, a form more appropriate than sculpture would be architecture. Although she has built two- and three-foot sculptures, she found their materials—steel cable, plexiglass and aluminum—less provocative than the gold, silver and precious materials she had become accustomed to. The intimacy and preciousness integral to her smaller pieces were lost.

Nevertheless, the precise sightlines, viewer position dependencies and engineering feats that some of her forms and angles suggest continue to convey architecture. Penzoil I is a reference to Philip Johnson's Penzoil towers in Houston. These two monumental towers stand with a narrow strip of air between them: Depending on the viewer's position, they can appear to be connected or to have a column of air separating them. Aguado's piece evokes the same enigma, though more intimately. A wall of 18-karat gold fronts a column of oxidized silver. Their connecting line depends upon where you are. Topped by an elegant magenta alexandrite, the piece is minimal yet opulent and luxurious, conveying an exotic contradiction and balance.

Aguado's pieces begin with rough sketches which she translates directly into metal. Despite their final precision, there are no precise renderings or models. "The metal itself is so informative," she explains "that models rendered in other materials which would forfeit its weight, color and balance would be extraneous at this stage." Yet when she feels she is not clearly visualizing the piece, she will make notes about what she feels the final piece should convey. Proportions are easy to sketch; visual illusions are not. Through words describing the intended visual effect, supplemental materials such as gemstones or acrylic are selected to convey the idea. She concludes: "Since heavy materials are used—metal and stone primarily—I continue to strive for an effect of visual delicacy."

Aguado creates rings to convey similar visual enigmas. She has constructed a large, man's ring, for example, as a silver box shaped to fit the finger. Where a stone might be, a mixed-metal plane recedes into the face of the ring. In another, a large, murky pearl has been set simply inside a silver box, as one might place a specimen in a laboratory case. She presents the mineral clinically, candidly. "If the interest is the rarity of the mineral or specimen, I don't want to intrude."

Aguado enjoys using rare and unusual stones which are either naturally phenomenal or unique in their cutting. She feels that when a client purchases a piece made by her with a stone cut by Bernd Munsteiner, whom she considers to be one of the best contemporary gemstone cutters, they are in effect investing in the work of two artists.

Aguado balances her own studio work with private classes. She is a member of the faculty of the New School/Parsons School of Design where she spends two days a week and has recently completed her master's thesis, "A Survey of the Jewelry Industry and the University Curriculum toward Restructuring the Training of Artist-Jewelers for Career Opportunities within the Jewelry Industry." "I'm interested in three things," she explains: "The education of young jewelers; the quality of the jewelry that is available to the public; and that there is more work for university graduates in this field."

A studio assistant and one intern from a university apprenticeship program usually assist Aguado in her studio. "For many reasons" she maintains, "it's reinforcing for goldsmiths to have others around, to share in the agony and the joy. . . . Because the concentration of working at such a small scale is so intense, I find it comfortable and rewarding to sometimes have someone else there while working."

Themes like those found in Night Trains and Facades are not originally conceived as belonging to a series. Rather, the series develops from an initial idea or visualization and continues, depending on what there is to sustain its growth. Currently, she is developing a series of sushi jewelry. A brooch of oxidized silver inset with carnelian and hematite spheres still on her bench, has a glittery wetness and freshness which clearly evoke salmon roe.

And there is the most recent piece, with a large 20-karat blue topaz cut by Munsteiner. The stone is held by a tapered baguette that pins it into a long slot cut in a silver wall. The slot is cut and tapered exactly to correspond with the cutting of the stone. Another wall of patterned silver topped with an 18-karat gold bar juts out of this silver wall at a 60 degree angle. The piece is a minimal, linear continuation of the planes and undercutting in the stone. Two lines cross each other according to the stone's configuration and then continue to influence suggestions of congruent triangles. It resembles a monumental girder and refers to astute engineering skills.

In allowing the piece to emerge from the stone, Aguado demonstrates her recognition of materials that define their own terms. It is this continuing recognition: the familiarity with material that permits the easy coincidence of economy and luxury; the effect of surface pattern and plane; the choice of material supplemental to metal that enable her to achieve the visual enigmas so important to her work.

Akiko is a freelance writer based in Manhattan

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.