Donald Friedlich: The Visual Articulations

15 Minute Read

Traveling down Stony Acre Drive in Cranston, Rhode Island, one cannot help but wonder at the use of this particular name for a road which repeatedly assails one with the monotonous banality of just another street in suburban America. Yet, on discovering the home of Donald Friedlich situated behind a silvered wood fence and ancient pines one encounters a farmhouse nearly 330 years old, with one end made entirely of stone. This anomalous dwelling suddenly makes this street's name seem extremely apropos, if only as a gesture towards the poetry which this house lends so greatly to the landscape.

As one enters this home one can immediately see Friedlich's aesthetic at work. The rooms are warm and inviting with subdued earth tones, edges and corners softened by time's passage and daily use, and asymmetrical angles that have been assumed as the house has settled into the earth over the centuries. Friedlich and his wife, Judith Mitchell have decorated these rooms rather sparsely with artifacts of various cultures and times, these are chiefly objects of use, such as vessels and tools. The somewhat spare decoration is not one of the dearth often evinced by emptiness, instead it is one in which each object - each bowl, spoon, rust encrusted key or handmade spade - has been placed with a care and concern which allows each piece a space and significance unto itself. Friedlich has succeeded in treating his home with the same deep consideration that he brings to the pieces which he creates for the human body.

Friedlich's aesthetic is an austere one. The marks, gestures, and various modalities of level and texture which he creates within a piece are often few and slight. His touch and its verities often appear subtle, seeming to grace the form he has chosen with all that it asks for, no more, no less. There is a note of restraint in his work which tells of the immense discipline he must apply to the creation of each piece, that tells of a consciousness ripe with a finely honed sense of balance. Each mark is considered, contemplated, and chosen for the specificity of its concision, the depth of its impress. The effect he achieves is one akin to the effect often experienced within nature - a quiet awe in the presence of an undeniable force, an effect indicative of Friedlich's paradigmatic understanding of timelessness.

Much of Donald Friedlich's life tells the tale of a self-described wanderer. His initial hero was Thomas Edison and as a boy he dreamed of being an inventor. In school he had an outstanding facility in both math and science. At eighteen he tried his lot at college, but after a brief stint there found that he was not at all inclined towards school and soon left, no closer to an image of his future than when he arrived.

An avid skier from the age of five, Friedlich then moved to Vermont and became a "ski bum", as he jocularly refers to his past self. There he continued to soul search and to try to "…decide what to do with my life". He related a rather telling "mystical tale" from that time: while he was living in a tent in the woods with a group of friends in Stowe, Vermont, He asked a friend who was extremely interested in the I Ching: "What does my future hold?". The reading came up as "power in the creative as yet unrealized". Friedlich staunchly attests to the fact that he doesn't believe in such "hocus pocus", but that, nonetheless, it did "prove to be quite accurate".

The "realization" came via a stone which he had found on the beach in Lambert's Cove, Martha's Vineyard in the summer of 1975, yet he did not know the significance of that stone for quite some time. Later that year he asked a jeweler friend to create a setting for the favored stone. She agreed to help, but insisted that he set the stone himself. He assented, and this encounter proved to be the beginning of the end of Friedlich's travels along the circuitous path that had thus far steered him through life.

He enrolled at the University of Vermont and began to take art and design classes, including every course which emphasized jewelry. With the help of jewelry instructor Laurie Peters, these classes began to stimulate and focus his interest in the medium, to build his confidence and proficiency, and helped to shape his vision. But he soon exhausted the rather scant offerings of the relatively small art department. A particularly meaningful class with Arline Fisch at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, along with the desire to further his studies, led Friedlich to the Rhode Island School of Design, where his most influential instructors were Jack Prip and Claus Bury. In 1982, after three years of study at RISD, he completed what he refers to as his nine year undergraduate career and received his B.F.A.

In his essay "Man and Creative Transformation" Erich Neumann refers to such a pivotal event in a person's life as an "irruption of the personality". When viewing Friedlich's work dating back to his first pieces created at the University of Vermont one can see evidence of all the facilities and intrigues of his life. The technical aspects of jewelry, which come with extreme slowness and difficulty to many a metalsmith, came easily to him - one can envisage the manual dexterity and intense concentration of the would-be inventor watching a new creation unfold before him. In the often clean, hard edge of his pieces one can see the hand and the mind of the artist who was an exceptional student in both math and science. The varied shapes and the pronounced textures which he generates through carving and sandblasting are indicative of his intense attraction to nature.

In most scholarship pertaining to contemporary art criticism the use of the words beauty and quality have become taboo as it is assumed that they connote a level of connoisseurship which is not accessible to the average person and, thus these terms are considered elitist. The fact that they spring immediately to this critic's mind upon viewing Friedlich's work would be considered by many a value judgment, yet I have heard these same words emerge from many an unschooled lip in reference to his work. The understanding and acceptance of such work is quite rare as Friedlich's language is not a common one in jewelry, but then again, Friedlich is not common. He has taken an aesthetic code, one often exemplified within nature, and brought it into a realm where it has not generally been thought applicable.

When queried as to what it is that particularly compels him about nature one finds that Friedlich's reaction cannot be concisely, verbally articulated. It is clear that Friedlich's work takes as its reference point an emotional, personal reaction; it has to do with a feeling which one experiences in the presence of any significant creation. But when this feeling is experienced in nature it is often connected with and furthered by the mystery inherent in that encounter. Friedlich utilizes the feelings which he experiences and translates them into his own visual articulation, processed through the various machinations of his distinct creative spirit.

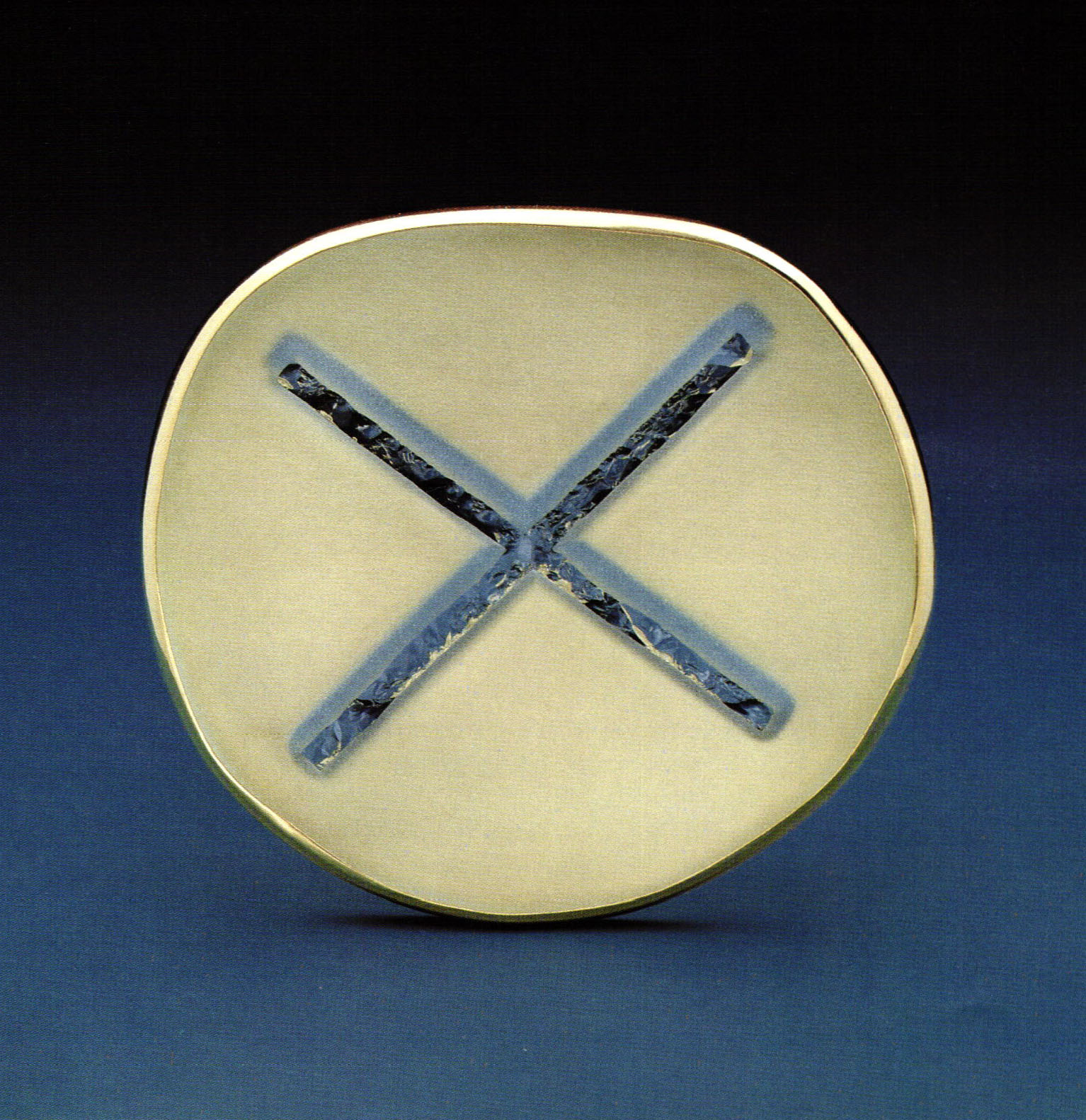

In the artist's own terms: "These pieces are studies in contrast. They are rough and smooth, geometric and organic, precious and non precious, positive and negative. The forms are monumental but the scale is intimate and appropriate for the human body." Upon inspection of the world around us one can see such "studies" abounding everywhere within nature. For example, in 1985 Friedlich was profoundly moved and inspired by a trip which he took to Arizona. He found himself enthralled with some of nature's most breathtaking vistas and monumental creations. In particular, he was intrigued by the effects of time and the forces of the elements which had enriched and articulated each natural form's particular material structure and composition. Two different series of work emerged from his travels in the Southwest: the Interference Series and the Erosion Series. Within these pieces he interprets the effects which the elements have upon nature's creations by cutting, sandblasting and carving the surfaces of his chosen material, generally slate or other stones.

In the Interference Series, geometric expanses of stone are divided or pierced by disparate elements of gold or carved troughs, much the way a seemingly invulnerable plain may be carved by a small stream. The brooches of the Erosion Series, most closely linked with the Arizona trip, have been carved into with a sandblaster, altering or softening their surfaces in order to emulate nature's process of erosion.

The artist's most recent work belongs to a series which he calls Translucence. They are made of sheets of glass which he cuts with a lens cutter. He continues to accentuate the "funky" edges of these forms by further carving and sanding them. After the initial cutting he treats the surface via his usual techniques of masking and sandblasting, sometimes adding another element of altered color to the design by backing the piece in metal.

The first thing one notes in this series is a striking difference from the work of the past in his treatment of the outside edges - the clean or jagged line is gone - these pieces are, more or less, round. Although he has been using glass for some time, chiefly in his Patterns Series (for which in 1988 and 1991 he was included in the New Glass Review of the Corning Museum of Glass) in choosing to utilize the form of the circle he has created quite a different ambiance within these pieces, one which is more receptive to the contours of the human body instead of opposed to them. In Friedlich's past work one notes the often severe contrast to the body - when a piece is worn it appears to be overlaid upon the body and separate from it. His recent pieces are more in tune with the human body, as if he has chosen another part of nature to incorporate into his work. The artist's creations have become more site specific. He has taken this work even further by making necklaces, a change from his usual brooches, which, again, makes the pieces more responsive to the body. In many of the objects Friedlich further integrates the work and the body by exploiting the translucence of the glass, allowing the character of the pieces to be transformed by the fabric of the clothing the wearer chooses to place behind it.

The painter Agnes Martin once said that the artist "creates to lend order to nature's often overpowering proclivity towards chaos". Yet if we put each element of nature - animal, mineral, vegetable - under a microscope what do we see? Although often abstract to the human eye via its sheer complexity, the composition of any given element of nature is, generally, an extremely ordered structure. An artist such as Friedlich does not feel the often desperate yearning of many towards control over nature, but instead he evinces an acceptance of it. Though we are all creations of nature with both chaos and order abounding within us, there is a tendency within human consciousness towards order and logic; and where have we teamed these concepts except by viewing and experiencing the world around us?

This aesthetic sensibility has long been a key with which the Japanese have approached their work and their influence can readily be seen within Friedlich's production. A number of critics have thus jumped on the facile accusation of appropriation of a cultural aesthetic in which Friedlich has no real roots or true understanding. I believe this interpretation to be a surface one. As Arthur C. Danto has said, "…deep interpreters always look past the work of art to something else". Any true knowledge of Japanese design points toward two influences - nature and materials - both chief sources of inspiration within Friedlich's oeuvre. In the west the tendency is to confront nature and to try and control it; in the east the tendency is to accept and enhance nature.

The factors which inform Friedlich's vision in particular are rather precarious when one tries to define them with any precision because they rest, chiefly, upon a certain refined sense of balance. To make this traditionally eastern aesthetic work within a given piece requires a great and deep cognition of this notion of balance, in visual terms a somewhat elusive word and concept at best. One can see a common thread running throughout the artist's work, which attests to an immense comprehension of this inclination, and the viewer is prone to think that this sensibility innate in Friedlich as it is so consistently and finely articulated.

Descriptive terms such as subtle, implying gentleness, and force, implying power. might seem at first glance contradictory terms. However, upon viewing any given piece which Friedlich has created one will see just why and how these adjectives are so applicable. To unify these seemingly incongruous elements of design and achieve any true harmony between them requires a sensibility such as Friedlich's, one marked with an exceptional respect for the immense grace and power of form.

Interpretation frequently assumes that there are various meanings within a given work which the creator himself may know nothing about. We could assume that Friedlich's vision of balance is purely a matter of personal taste. Balance, after all, was a significant element in the art to which he was drawn during the initial art classes he took at the University of Vermont, and in the objects he has chosen to decorate his home. Another profound and lasting influence from his early years of exploration and development was Hideyuki Oka's How to Wrap Five More Eggs, a book of photographs of traditional Japanese packaging. Friedlich refers to " . . . the simplicity and order of the Japanese garden, the stability and refinement of geometric forms, the delicacy and texture of handmade paper and the monumentality and power of geological formations", as being among his chief inspirations. He also notes: "In addition the stone sculpture of Isamu Noguchi, the abstract landscape canvases of Richard Diebenkorn and the natural site specific sculpture of Andy Goldsworthy are close to my heart."

What do all of these references have in common?: Nature, and the materials of which it is comprised. One notices in Japanese packaging the extreme care and attention that is paid to each element, no matter how simple or seemingly unimportant. To the Japanese all objects are objects of value as they comprise elements of the life in which we are daily engaged. Thus, as everything we come into contact with effects us in some way or another, logically, the experience of that object should be a pleasant one. Friedlich felt the richness in this experience of and attitude towards life and has chosen to create objects which can bring such experiences into wearers' and viewers' respective lives. His work reveals an appreciation for the smallest details and a vision which finds pleasure and meaning in the dramatically different composition which results from the smallest change - slightly moving a carved element, turning a small triangle of gold on its side.

Simplicity, order elegance, balance are all words which come to mind upon experiencing certain works of art, pieces of music, literature, and places in the world both inside and out of nature. But what do these words mean to us, exactly what do they imply? Such precepts as those set forth in Zen philosophy would maintain that simplicity connotes truth. Truth is, of course, an utterly subjective matter, but the element of simplicity which seems to guide Friedlich's aesthetic has to do with his respect for the poles of power and grace. He articulates his visions and representations of these poles without clouding his depictions with myriad superfluous or arbitrary embellishments of decoration, which would only lead the viewer's eye away from the point of the piece. That is truth. Incisive articulation of the notions of order and balance, such as those illustrated within Friedlich's oeuvre, have to do with acknowledging that intense opposites do, indeed, exist, but that they also coexist. Heeding this sense of order and balance lies in not making a choice between these poles in terms of preference for one way of thinking, seeing, or feeling at the cost of the other. It is instead a matter of acceptance, acknowledging and allowing that each pole exists; regarding each with justice and conceding to each their own validity.

Within Friedlich's production one can both see and feel representations of true acceptance and true allowance, depictions which are dense with his visionary comprehension. We may call the gestures evinced within his work elegant because they do not manifest the strident call of man, the harsh call of an ego imposing itself upon a given piece. Friedlich's creations are a tribute to the world around him, a response to the richness and wonder which the experience of life has brought to him. His pieces are ways of reciting experience and passing it on as filtered and articulated through his own unique and fecund vision.

Paul Valery's essay "Man and the Sea Shell" raises a question pertaining to a human being's reaction upon encountering a masterpiece of nature's creation. That initial question, if we were to acknowledge our naiveté, would be "Who made this?" Making immediately comes to mind, and with this awareness comes the conception of a consciousness that must have designed this thing, must have thought it out. But the only answer to the question of who designed a natural object would be, necessarily, a subjective one. There is a certain magic in the notion that the creation of nature and that which resides within it is an enigma forever irresolvable. Friedlich has felt this magic, and where he sees the intersection between human and creator is within this world, upon this earth we daily tread.

Claire Dinsmore is a writer who lives in Princeton, NJ.

Notes

Conversation with the Artist, January 17, 1995

Ibid.

Eric Neumann, Art and the Creative Unconscious (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1959), 152.

Conversation with the Artist, January 17, 1995.

Ibid.

Agnes Martin, Catalogue of Retrospective Exhibition. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992), 3.

Arthur C. Danto The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art. (New York: Columbia Univeristy Press, 1986), 47.

Donald Friedlich, Artist's Written Statement, 1995.

Hideyuki Oka, How to Wrap Five More Eggs. (New York and Tokyo: John Weatherhill, Inc., 1975), 7 - 13.

Shin'ichi Hisamatsu, Zen and the Fine Arts. (Tokyo: Kodansha International. Ltd., 1971).

Paul Valery, An Anthology (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1977), 108-135.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.