Doneghy Collection of Southwest Indian Silver

9 Minute Read

At a time when the country is still reeling from the vogue for Indian jewelry displayed around the necks of rock stars, like the chains of the Lord Mayor, and on the blue jean shirts of admirers of "the Santa Fe look," it is refreshing to be offered the opportunity to see the Virginia Doneghy Collection of Southwest Indian Silver.

The handsomely displayed pieces represent a half-century of purchases made by Virginia Doneghy, an intrepid librarian from Minneapolis, during her yearly vacations in New Mexico and Arizona. Describing her first encounter with Indian jewelry, Doneghy recalled an early visit to Santa Fe. The bus on which she was riding stopped in front of the gift shop window of La Fonda Hotel; there behind the glass she caught sight of a silver necklace. "To me," she said, it was "the most beautiful necklace I had ever seen."

After fiesta ended, she returned to the shop; the necklace was still there just "as beautiful on close inspection as it had been from the bus" (Southwest Indian Silver from the Doneghy Collection, ed. Louise Lincoln, p.182). This was the beginning of a lifelong love affair which focused upon the work of the Navajo silversmiths.

The silver collection consists of 1200 pieces: concha belts; bracelets; ketohs, bow guards of silver attached to leather; rings; pouches decorated with silver; pins; earrings; buttons; beads; squash blossom necklaces; even a headstall for a horse. Chosen by Doneghy with an unwavering taste for excellence, the Indian jewelry forms an important visual document which contributes insights into the technical changes and stylistic developments that have occurred in the century between 1870 and 1970.

The earliest pieces acquired by Virginia Doneghy belong to the last three decades of the nineteenth century. The craft of working metal was probably taught to the Navajo, in the 1850s, by Hispanic blacksmiths; but it is likely that the Navajo did not work with silver in a serious way until after their return to their homeland from the terrible years of confinement at Fort Sumner—a captivity which ended in 1868. The fact that the Indians were allowed access to iron and brass and to copper wire stockpiled at the Fort, and also to the forges seems to have played a role in the rapid development of silversmithing in the 1870s and 1880s, decades that became known as the "classic era" of Navajo silver jewelry making (Margery Bedinger, Indian Silver, p.41).

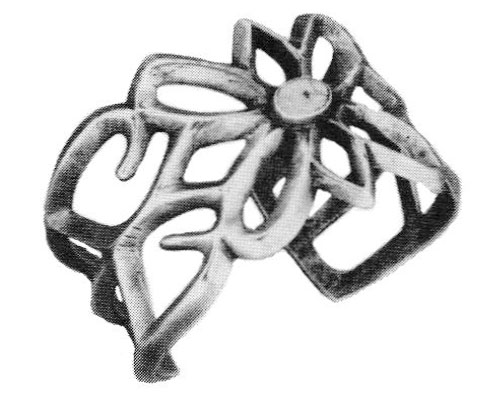

Bracelet, 1910-1920. Cast openwork band. Set with round and oval cabochon turquoises

At first, the silver used by the Navajo came from U.S. coins. When this source was banned in 1890, by an act making it illegal to deface the currency of the United States, Mexican silver was substituted. The first ornaments depended upon annealing and hammering the silver. Stamped designs were struck on the metal as an added decoration. The Navajo borrowed the idea of stamping patterns on their silver work from the Mexican plateros, itinerant silversmiths moving along the trails of the Southwest. The first markings made by the Navajo resulted from striking a chisel against the surface of the silver or by using a small metal pipe to indent a series of crescent shapes.

By the 1870s, silver casting was practiced by the Indian smiths. If an object required several silver coins, the smith would melt the necessary amount of metal and pour it into an ingot, roughly approximating the desired form. When the silver cooled, the ingot was hammered into a thin sheet, on an anvil often made from a section of railroad track, and then trimmed. A more direct method of casting was accomplished with a two-part mold carved from sandstone found on the Navajo Reservation. This method continues to be used for the bold, openwork designs which are among the finest products of the Navajo and Pueblo craftsmen. During the last part of the nineteenth century, the techniques of appliqué and, repoussé were perfected. This was also the period in which the Navajo smiths learned how to set stones in silver. The stone was secured to the metal by a tightly gripping band of silver; the resulting bezel was soldered to a bracelet, ring or other piece of silverwork.

Ketoh, cast openwork mounting on leather band; set with elliptical cabochon turquoises in serrated bezels, stamped decoration, about 1920

Unlike the Zunis, who specialized in lapidary skills and allowed their use of turquoise to dominate the silver, the Navajo never permitted stones to diminish the contributions of the silversmiths or the turquoise to detract from the smooth sheen and sculptured quality of the metal. When selecting a stone for a setting, the Navajo preferred a large single turquoise cut in an oval, a circle or in a rectilinear shape. A cluster of stones might be arranged around a central stone; for a narrow bracelet. Turquoise was repeated about the band. Compositions developed a firm symmetry, varied by linear repetitions. An admiration for massiveness and balance characterized the goals of the Navajo craftsmen.

Navajo jewelry made to be worn by Indian family members had nothing in common with the "made-on-the-reservation" work commissioned for the purpose of attracting tourists who flocked west by rail and auto in the 1920s and 1930s. Light-weight silver with badly matched turquoise and stamped with so-called "Indian symbols," thunderbirds, owls, swastikas and crossed arrows, satisfied the desire for souvenirs. The Navajo looked at such symbols with disgust. Figures associated with religious ritual or the traditional sandpaintings that accompanied the healing chants were too sacred to be worn as ornaments.

Bracelet, cast openwork band set with large calcedony, 1930s

The popular and elegant squash blossom necklace became a special prey of the invented interpretations of wily tradesmen, although its true origins were far more fascinating than the hints of erotic meanings. The necklace consists of silver beads alternating with the blossoms, whose long shanks are pierced for stringing and attached to a round bead, at the end of which pieces of silver are soldered and curved outward like petals. Although there is a resemblance to the flowers of the squash plant, the motif is more closely related to the pomegranate, which flourished in the south of Spain and was grafted onto the coat-of-arms of the city of Granada. Beads with the pomegranate motif were brought to the New World by the Spanish; such beads were often sewn on the jackets and trousers of the Mexicans (p.83).

The third portion of the necklace is a silver crescent , or naja, suspended at the center of the string of beads and squash blossoms. Like the pomegranate design, the naja also made its way across the Atlantic from Spain; but its first emergence was much earlier, perhaps, in the dim light of prehistoric caves. Cave dwellers are thought to have fastened the tusks of boars together in order to assume for themselves the animals' strength and ferocity. In Rome, the crescent appeared on horses' bridles as a protection against evil.

Bracelet, cast band with pear-shad turquoises in serrated bezels; stamped decoration, 1930s

A Navajo named Long Moustache is quoted by Bedinger as explaining that the naja was placed at the center of the headstalls of Indian Ponies to give them greater speed; he added that the crescent probably was suggested by "observing the moon scudding swiftly through the clouds" (p.79). This is, doubtless, more fanciful than accurate. The tips of the naja terminate in plain circles, turquoise stones or tiny hands. The hands point directly to Islam and to the Moors who carried the naja with them when they crossed the straits of Gibralter into Spain in the eighth century A.D. The hands are a reminder of the magical power of the "hand of Fatima" worn as an amulet to counter sorcery and guard against the evil eye. The Navajo often suspended a turquoise within the open circle of the naja. Without conscious intent on the part of the silversmith, at the intuitive level, the naja gains richness by linking its graceful design with the round hogan, the traditional house of the Navajo, and its only opening, or door, at the east in the circle. The central stone recalls the location of the hearth-fire at the heart of the home. The naja is also a reminder of the open-ended rainbow, or mirage, placed protectively around many of the sandpaintings which, at the time of a chant, are made inside the hogan.

Louise Lincoln finds a correlation between the sacred landscape of the Navajo, bounded by sacred mountains at each of the four points of the compass, with a vertical line representing zenith and nadir rising at the center, and the tendency of the Navajo silversmiths to divide a surface into quadrants with a strongly defined focal point (Southwest Indian Silver, p.43). This is particularly apparent in the designs of the ketohs. But more than the strands of associative meanings that are Present in all aspects of Navajo art and life, it is the spirit of. hôzhô that permeates all things. Although hôzhô (may be translated as beauty, in the context of the Navajo language, its significance is broader, richer, and more subtle than the implications of the English word. Hôzhô Penetrates beneath the visible, outer form of all things, animate and inanimate,, to the state of beauty that lies within.

Bracelet, cast openwork band; set with small, flat, elliptical turquoise, about 1950. Photos: The Minneapolis Institute of Art

To "walk in beauty" is the correct path through life. Hôzhô contains the concept of order, balance, stability and accord. Lincoln Points out that it is not enough to consider the completed work of art, because the process which brought the work to completion is equally important. From the Navajo perspective, she says, a piece of jewelry "is merely the vehicle whereby beauty, hôzhô is transmitted from an artist, who is himself in a state of beauty, to a recipient or audience, who will in some measure be brought into a state of beauty through viewing, wearing or appreciating what the artist has done and made" (pp.40, 41).

It is the state of hôzhô that Virginia Doneghy must have shared with the silversmiths whose work she bought year after year. She did not deviate from a trust in traditional values and the gentle progression of designs passed from one generation to another. In adopting this criteria, she by-passed some of the new trends developed by Indian jewelry makers in the Southwest; she chose, instead, to build a collection that is remarkable for its devotion to the best of traditional values. In choosing this path, she provided a valuable legacy for all who are interested in studying and contrasting the silver made over a century of technical developments and changes that did not reject the old because it was old, but allowed designs to evolve.

This exhibition, circulated by The Minneapolis Institute of Art, was reviewed at The Texas Tech University Museum, Lubbock, Texas, where it was on view from January 15-February 15, 1983. It will travel to The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, December 7, 1983-February 26, 1984 and to The Cooper- Hewitt Museum, New York City, April 17-July 8, 1984.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.