Ed Wiener: Arts and Ends

14 Minute Read

Ed Wiener exemplifies the studio jewelry artist of the late 1940s and 50s. The first time we met, this fascinating 70-year-old man reminisced at length about the New York art/craft scene of 40 years ago. With a wry wit and an acute intellect, he interpreted an era, a philosophy, a movement, only now coming to be understood as the post-World War II American metalsmithing phenomenon, and expounded upon its unique connection to modern painting and sculpture.

In reviewing my interviews with him for this article, I was impressed with how much I had learned about jewelry from looking through his eyes, and how much more fully I appreciated the innovations pioneered by the vanguards of this revolution.

His verbal approach to the pieces focused on design elements and/or concepts, while his visual approach in handling a bracelet, rotating it, placing it on my wrist pointed out how the air, enclosed by a simple curve of wire, gave the piece its impact. Further, his comparison of its relationship to the sculpture of Alexander Archipenko (Figure 1A, 1B)— how the negative space creates the "magic," allowed me to view modernist jewelry with a more clearly sharpened perception.

Because Wiener is currently preparing a retrospective exhibition, his position in the scheme of contemporary jewelry history was on his mind. What began 40 years ago as a means "of supporting himself and his family with dignity" developed into a varied technical and stylistic evolution—an intensely intellectual approach to the creation of jewelry with the methods available to him. He wished to exhaust a particular mode and move on, not overcraft a piece or combine too many images or techniques.

A simple man, Wiener believed in reducing a design to its essentials, eliminating extraneous elements. He compared jewelry design to jazz improvisation, where chordal embellishments build up until they become more important than the harmony itself, after which the musician deletes, paring the passage down to the core—the most brilliant tonal statement being left—just as in exceptional visual design. He admired the integrity of jazz and how jazz musicians likes modernist jewelers found a technique to express their artistry.

He believed, as did his contemporaries in 1946, in a noncompetitive alliance among artists—in a new world, where one shouldn't regress. The American studio jeweler was unfeuered by tradition, unlike his European counterpart. He firmly believed that an artist must be involved in the basic problems of his time. He leaned towards nonobjectivism, but with subliminal clues. i.e., using non-representational forms to suggest the recognizable: an ovoid might indicate a TV screen or a five-pointed star a person. Ultimately, a bird is not a bird but a "feeling-off-light form."

Like so many modernist studio jewelers, Wiener was essentially self-taught. Born in New York City in 1918, he worked in his father's butcher shop until the war. During WW II, while working on a radio assembly line, he realized he had an aptitude for manual skills.

And after the war, in 1945, although he had no real interest or background in jewelry or art, he took a general craft course at Columbia University, as he puts it, in order to accompany a friend who was getting her masters degree in art education uptown on the subway. The craft class lasted for three months with only four sets of tools for 50 students. The kitchen stove, where he worked with his wife, Doris, became his first studio. There the Wieners fashioned pins with their friends' names and initials from twisted wire. They were instantly successful and the proceeds from their sale paid for tools. Wiener states, "[It was a] wonderful way to digress from a rather drab world of simply earning and trying to find expression."

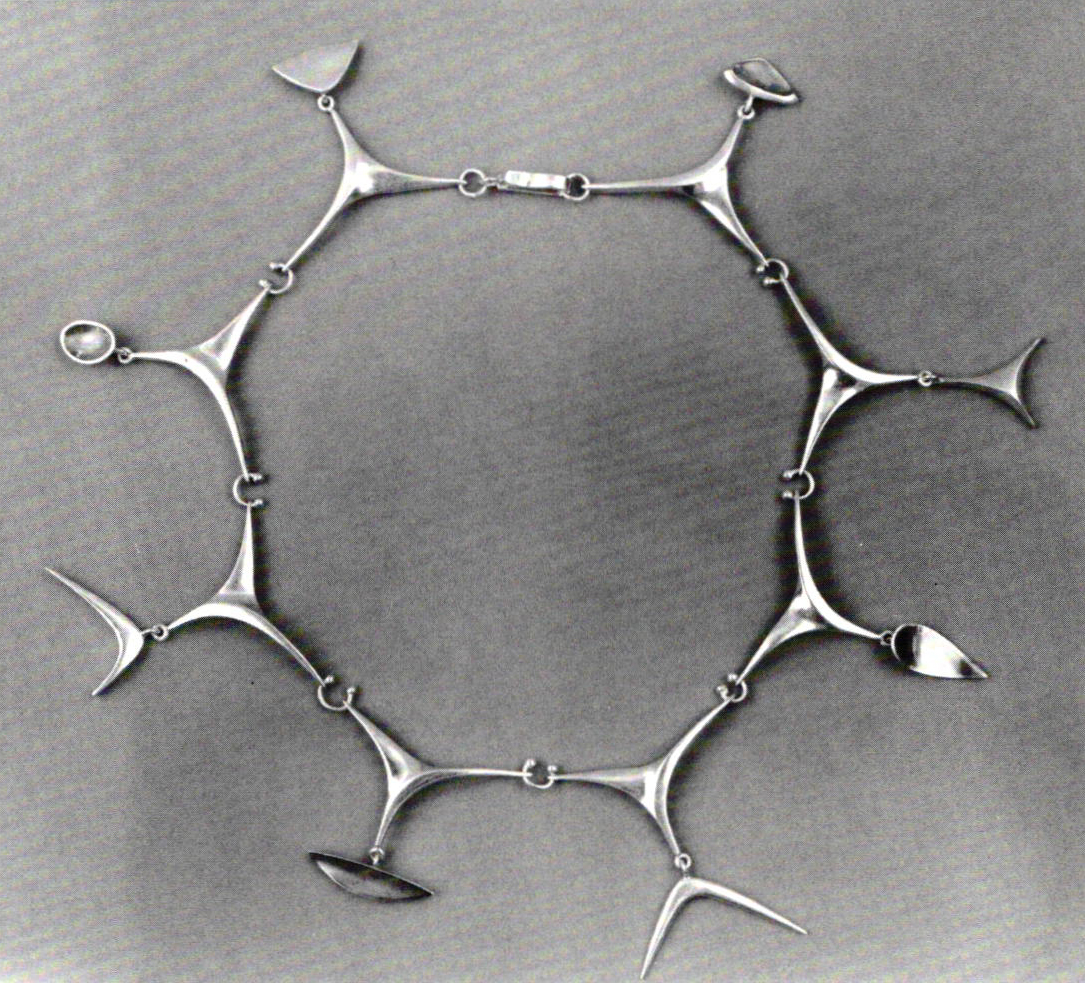

Married in 1944, Ed and Doris Wiener went to Provincetown for the first time July 4th weekend of that year. They instantly fell in love with "this brilliant little gem of a town on the perimeter of Provincetown Harbor . . ." The picturesque qualities of this beach community surface, continuously, in his imagery: sea urchins (Figure 2), decaying driftwood (Figure 3), and "big fish eating little fish" (Figure 4). Wiener feels a psychic connection with natural forms and desires to express nature's ambiguity, e.g., the fact that the sun, sand and water can maintain as well as corrode, material. Furthermore, natural forms are elegant and elegance is one of the things jewelry should be about. Attracted also by the artists' colony and exotic bohemian atmosphere, they decided to return every year.

They opened their first store in the center of Provincetown during the summer of 1946, in a space they shared with sandal-maker Roger Rilleau. There the Wieners sold Mexican jewelry (which was not so popular then), as well as Mexican bags and belts, along with their own creations. Working 14 hours a day, seven days a week, they lived a primitive existence, taking the afternoon off to bathe in Wellfleer Pond, as they didn't have a tub. Wiener learned a great deal from the artists who frequented his shop: Harry Engel, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Peter Grippe, Chaim Gross, Hans Hoffman and Ward Bennett, all of whom, he notes, were ". . . willing to suspend a certain amount of taste to help a struggling young artist." They made him feel as if he was doing something significant. There were very few standards in contemporary jewelry at that time by which to judge, the prevailing modern style being Danish modem, exemplified by Georg Jensen.

Feeling that jewelry should be a contemporary expression, he first looked to Picasso for inspiration. Picasso's sculptural forms, especially, were very readily translatable into jewelry, especially silver, which was used primarily because of its impermeability. "[Silver] is a noble metal . . . "It'll be beautiful in spite of most things you can do to it," Wiener later remarked. The logical conclusion of his love of silver was to use a lot of it, so the early pieces tend to be heavy, incorporating tool marks and, thereby, the idea of process, into the design. (Figures 5, 6, 7). He admired Calder's disregard for prevailing jewelrymaking conventions, for example, in creating earrings that were too long—mobiles, really, with the ends left unfinished, just hammered a little, and the surface dull instead of shiny, planished instead of smooth. This helped him break out of the two-dimensionality of his Picassoesque period. Wiener was inspired by Calder's rhymatic expansion of round wires by the occasional flattening of a section and, consequently, achieving disturbance of the uniform parallel quality (Figure 5) and by the primitive technique of twisting wire to form connections rather than soldering (Figure 7).

In the summer of 1947, the Wieners opened their own shop in the western part of Provincetown, across from the Advocate Building, where they also sold painting and sculpture by other artists, and they occupied this gallery every summer until 1965.

Upon their return to New York in the fall of 1946, the Wieners rented a studio on Second Avenue and 2nd Street, in what is now the East Village. In the winter of 1947, Wiener opened his first retail store on 55th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, in the ground floor of a brownstone, several steps below street level Architect Dick Stein designed a tight, "Mondrianish" space. The store, called "Arts and Ends" (with "Ed Wiener" printed below in small letters to avoid confusion with another jeweler Edward Weiner, who had already registered his business in that name), remained at that location until 1953. Wiener attributes the prevailing interest in post WW II studio jewelry and his clientele, made up, mostly, of artists, art teachers and art collectors, to the landmark modern jewelry exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946, because it was dominated by contemporary sculptors. It caused handcrafted jewelry to rise above the realm of occupational therapy.

Further encouragement to explore the creative possibilities of contemporary jewelry came from his friendship with Sam Kramer and his respect for Kramer's inspirational manipulation of gauge and volume (he had purchased a pair of earrings from Kramer for Doris in 1938 for $2.50).

Wiener's own formal vocabulary was most influenced by Calder's use of spirals (Figures 5, 8), ovoids and inverted Cs (Figures 9, 10, 4), and the manner in which the forms floated, relating to one another (Figures 11, 4). These shapes and configurations span Wiener's entire career. Following the wire calligraphy in space, his design repertoire began to include expressions of volume through oxidation, enclosing walls and low-negative forms (Figures 12, 1A & B, 2). He explored linearity and volume simultaneously from 1946 until about 1953, cross-fertilizing each other and breeding new forms and reconciliations. Wiener constantly set up a "problem-solving" situation with an intellectual solution, feeling that he was more influenced by painting, but, at the same time, caught up in the three-dimensional context necessitated by the jewelry object's function within the body's space frame.

Wiener's concern with movement led to his playful "abacus" pieces (Figure 6), where beads would move freely on suspended wires of varied lengths and, sometimes, gauges. But there would, ultimately, be a spot where the bead would be caught, not allowed to move completely freely, which revealed the ever-present imposition of a formal solution, a controlled haphazardness.

From 1953 until 1966, "Arts and Ends" occupied a store at 46 West 53rd Street, a "high-traffic street" near the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. A second store was located in Greenwich Village until 1958. The earliest wrought expressions eventually acceded to what Wiener terms the "ultimate sculptural context" (Figure 13), which he admits he resisted for a long time. Jewelry has two essential functions, according to Wiener, to adorn and to modify the human figure. His strong beliefs about the role of scale in jewelry and its relationship to the human form have kept him away from making purely sculptural work. While sculpture exists only for itself and is suspended in its own space, jewelry needs a person's anatomy to find its resolution: ". . . all designs shall lie in the human scale and shall express the wearer," Wiener states. "There is a constant need to test against the human figure; I reject a design in jewelry that I feel is purely sculptured." Also, jewelry must be handsome, he believes. It is often worn as a cultural badge of rebellion, to visually associate oneself with contemporary art.

An icongraphic motif runs throughout all of his periods, often obvious in ethnographic or figural associations, sometimes alluding to the beach, sometimes to primitive and/or tribal (Figure 9). These images were achieved in both wrought and cast techniques, the later being explored fully from about 1949 on.

Metal's ability to reflect light and thereby define a piece through its silhouette is a key point in understanding Ed Weiner's vision. Texture intensifies the formal definition through its lessened reflective properties. The transitional pieces—accretions or combinations of random forms (Figure 3) display deep texture and foretell the important diverse direction Wiener would be taking in the 1970s.

Wiener's next move was to Madison Avenue at 69th Street in 1966. By now his textural applications were becoming more subtle. A visit to the stone room at the Cluny Museum in Paris and a trip to the gemcutting centers in Jaipur, India excited him and extended his imagination as to the use of stones mounted in gold. He became enthralled with Byzantine jewelry with its connecting link between Europe and Asia, a compromise between West and East.

Use of stones, which he bezel-set, as did the ancients, further offered him a means to connect with the pre-Renaissance past. He began to favor high caret gold for its predictability, although he gave it a dull finish. Rings were his favorite types of jewelry because of the amuletic connotations and symbolic properties of power and/or high social status (Figure 11). He has made five times as many rings throughout his career than any other jewelry object. Some stones have magical meanings, such as abstract powers to avert disease or bring good fortune. As he notes, ". . . people have this external vision of themselves that somehow, some object in nature or something can fill up their own lives; a power that they lack in themselves. And that it can fulfill them far beyond ownership and its fashion meaning. . . ."

Although Wiener is not a religious man, he makes primeval spiritual associations in his jewelry. "I seem constantly to dredge up older and less articulate cognitions of gold like sunlight, and gens like water and fire and all are full of magical and symbolic energies". He employs what exists between the material and the maker to achieve a deep view of what exists inside himself through images he digests from his environment.

Unlike his early wrought-silver pieces, which explored both positive and negative forms—mass and void—jewels from the textural periods derive their form from the surprise configurations created by the stones, the color of the gold and the texture. Deliberate randomness in the arrangement of the stones (Figures 11, 14) calls to mind similar tense combinations in metal and vacous shapes from earlier periods.

From 1971 to 81, Wiener maintained a shop at 57th Street and Madison Avenue. During this period, he was heavily involved with textural effects on gold. However, the texture became subtle, volume was achieved through surface (Figure 14).

Ed Weiner is now immersed in what he terms "The Great Reprise." One sees in his newest output from 1986 to 87 an artist looking both backward and forward. Original forms reappear with more spectacular dimensions (Figures 4, 8). The spiral—immutable, infallible, has coiled for Wiener for 40 years and gives no indication of ceasing (Figure 8), and the primal symbols of sea life reemerge with a new textural surface (Figure 4).

Images from mankind's "collective unconscious" (Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols) have been drawn with metal by Ed Wiener, in most techniques available to the contemporary metalsmith, and now are reappearing to be refined. And this is Ed Wiener's contribution: Sam Kramer, Paul Lobel and Margaret de Patta were well established by the time he came on the scene in 1946, but no other jeweler of that generation explored so many different approaches so successfully. He has a brilliant sense for shape, surface and volume. The pieces are subtle, often disarmingly simple. They must be touched, turned, worn.

Ed Wiener was not competitive. He was not in the craft mainstream. He only wanted to make the best pieces of jewelry he could. He was surprised by his success and only recently is able to evaluate this significance objectively. "Jewelry," he says, is a "gift of love." And if a piece is made to be such and is given in that context, it is cherished. To Ed Wiener, this is what jewelry is all about: the magic, the mystery, the spirit, the energy and the change.

Through each period and style in which he worked, he always strove to be a jeweler for the current time. He found inspiration in sources as diverse as modern painting and sculpture, nature and primitive symbols and ancient techniques. "In the end," he says, "we never really broke from tradition." He has been a modernist, a retro-modernist and a post-modernist. I look forward to what he will do next.

Notes:

- From an interview with Dorothy Seckler for the Archives of American Art, Sept. 5, 1962, Provincetown, MA. 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- "Arts and Ends," Craft Horizons, Spring 1950, vol 10, no 1, p 23.

- Whitaker, Irwin and Wiener, Ed, "Jurying on Trial," Craft Horizons, Sept/Oct, 1957, vol XII, no 5, p 33.

- Idem, Seckler.

- Ibid.

- Nordness, Lee, Objects U.S.A., New York: Viking Press, 1970, p 209.

- Idem, Seckler.

- From an interview with the author, July 28, 1987, New York.

Bibliography:

- Interview with Dorothy Seckler, Sept 5, 1962, Princetown, MA.

- Interview with Sarah Bodine and Michael Dunas, June 9, 1987, Ed Wiener's New York studio.

- Interview with Toni Lesser Wolf, July 28, 1987, Ed Wiener's New York studio.

- Whitaker, Irwin and Wiener, Ed, "Jurying on Trial," Craft Horizons, Sept/Oct 1957, vol XII, no 5, pp 32-33.

- "Arts and Ends," Craft Horizons, Spring 1950, vol 10, no 1, pp 22-23

- "Radakovich," Craft Horizons, Sept/Oct 1958, vol XVIII, no 5, p 31.

"American Jewelry 1962," Craft Horizons, Mar/April 1962, vol XXII, no 2, pp 31-38. - McDevitt, Jan, "The Craftsman in Production," Craft Horizons, Mar/April 1962, vol XXIV, no 2, pp 21-28.

- Slivka, Rose, "The American Craftsman 1964," on jewelry, Craft Horizons, May/June 1964, vol XXIV, no 3, pp 69-73.

- "Twenty-five Years of Craft Horizons," Craft Horizons, vol XXVI, no 3, June 1966, p 71.

- Kwong, Kui Ka and Cumrine, James, "Dialogue in a Museum," Craft Horizons, July/Aug 1967, vol XXVII, no 4, pp 19-20.

- Nordness, Lee, Objects U.S.A., New York: The Viking Press, 1970, p 209.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.