Ellensburg Funky

10 Minute Read

Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington, is ninety miles east of Seattle across the high Cascade Mountains range and a world away from the comparatively sophisticated cultural institutions of Puget Sound. At least two local variations of art movements, Funk Art and Found Object Jewelry, got their start there or were redesigned and retrofitted to suit the needs of the students and teachers.

While Davis, California may have been the Athens of Funk, Ellensburg was its Alexandria, a willing provincial outpost with its own learned clutch of followers. The closer one looks at the oeuvres of the major post-1970 artists - Don Tompkins (1933-1982); Ken Cory (1944-1994); Merrily Tompkins (b. 1947); Nancy Worden (b. 1954); and Ed Wicklander (b. 1952) - the easier it is to realize the differences between these individuals and the California Funk artists like William T. Wiley, Robert Arneson, and Robert Hudson.

Institutionalized for the first time in a 1967 exhibition at the University Art Museum in Berkeley by director Peter Selz, the style was the subject of Selz's perplexed catalog essay, "Notes on Funk". He agreed with artists who told him, "When you see it, you know it." Nevertheless, he pointed out several aspects that are pertinent to a discussion of the Ellensburg Funky style:

Funk art is hot rather than cool…it is bizarre rather than formal…it is sensuous.

Selz, a leading authority on twentieth-century German art, traced its attitude back to Dada and Surrealism, updated it in relation to the early work of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns to give it a fine-art sheen, but set it in opposition to Pop Art.

Moving north by northwest, Funk art became all the rage in West Coast university art schools. Its irreverence appealed to the young; its adaptability and non-hierarchical attitude about materials appealed to craft artists. From Davis to Las Vegas; from Eugene to Boise; from Corvallis to Pullman; north to Ellensburg, and even to Bozeman and Missoula, Calgary and Regina, Funk art freed regional artists from the pressures of the dominant style of the day, Modernist abstraction.

At the same time, an earlier C.W.U. professor of jewelry Ramona Solberg (b. 1921) widened the net of possible materials even farther to incorporate references to ethnic art, talismans, and amulets. According to Worden, an artist and former student at C.W.U.,

…what always made Central different was that we were jewelers. Don, Ken, and Ramona knew how to forge but they never taught it…They were closer to anthropology than art, more cultural, interested in how jewelry intertwines with people's lives.

With that appreciative ground, artists such as Worden, Merrily Tompkins, Cory, and Wicklander combined the love of found materials with other aspects of Funk they found appealing: subjective content, sexuality and humor.

Although there were many other teachers and artists at C.W.U. with similar affinities to Funk, a few concentrating on jewelry and metals are the subject of this essay.

An extraordinary figure long neglected in American jewelry history, Don Tompkins studied art and art education at the University of Washington after a strong high-school program under Russell Day in Everett, Washington. He began graduate work in Seattle but also studied at the School for American Craftsmen in Rochester, New York and at Columbia University Teachers College where he received an Ed. D. in 1973. His dissertation dealt with historical precedents for jewelry as fine art.

Strictly speaking, Banting and Best, Jackson Pollock, and, Richard Nixon (Commemorative Medal series) (1969-72), are pre-Funk, more New York Pop Art. Living in Manhattan in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Tompkins was an active participant in the nascent SoHo art scene while he was a graduate student at Columbia. He owned a studio, Jewelry Loft, where he sold necklaces and pendants based on current events of the day. Other subjects commemorated were political figures like J. Edgar Hoover, Martha Mitchell, and President Theodore Roosevelt (whom Tompkins was said to resemble, hence his nickname "T.R."), musician Janis Joplin, writers Norman Mailer and Henry Miller, Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner, and art-world luminaries Pablo Picasso, dealer Ivan Karp, and Claes Oldenburg. These objects comprise an important body of work which satirizes American society in pendant-necklaces of great linear delicacy, impeccable composition, and withering wit.

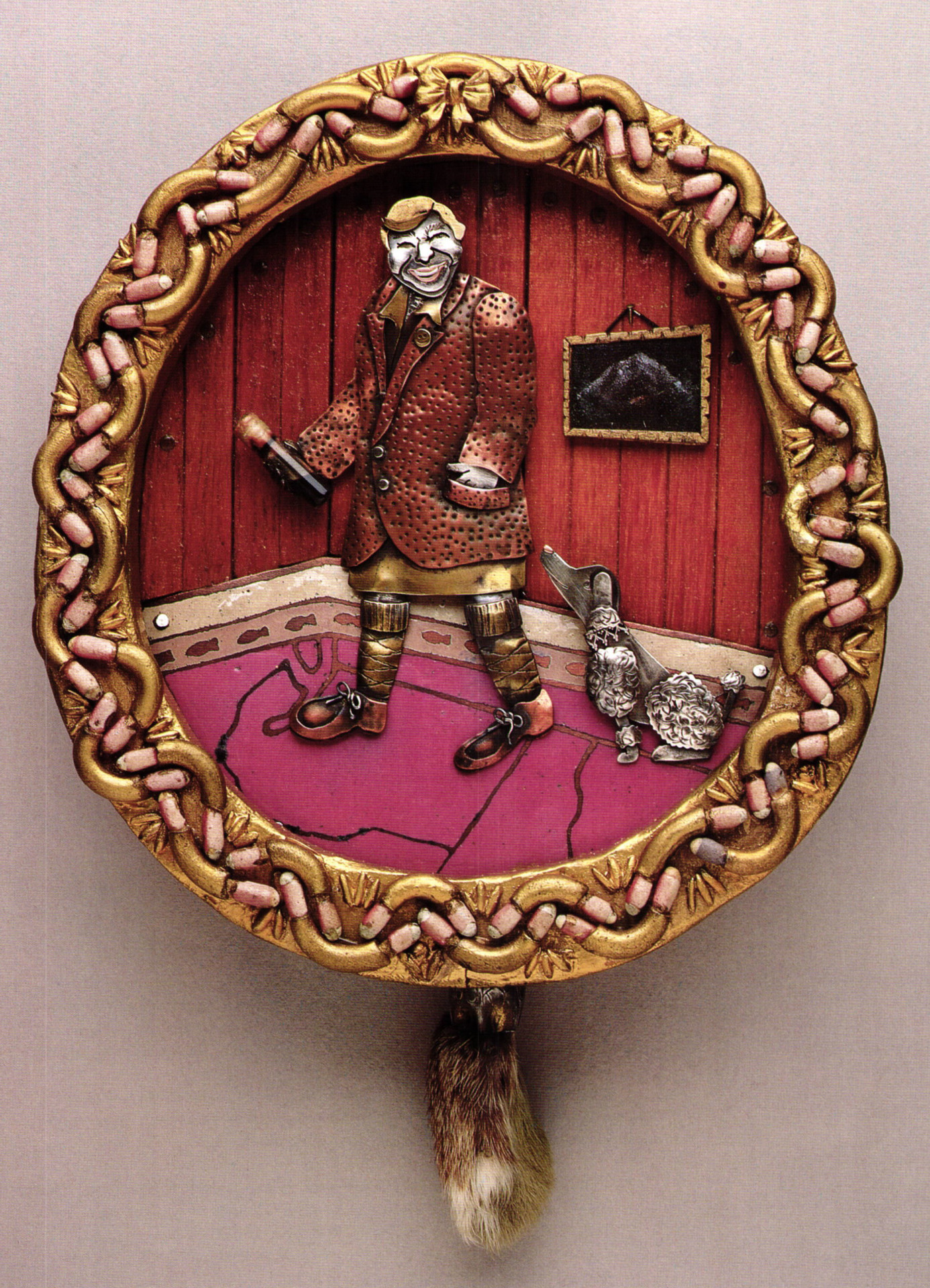

Nearly ten years after his kid sister, Merrily, studied with him in 1968-69, she made A Woman and Her Dog (Gov. Dixy Lee Ray) (1977). Borrowing her brother's commemorative medal format, Tompkins celebrated and vulgarized in true Funk fashion the state's only woman governor, Dr. Dixy Lee Ray, ex-director of the Atomic Energy Commission and blatant apologist for corporate pollution sins.

With her love of folk art (and her folk artist father) and its often unapologetically sloppy construction, the younger Tompkins chafed at the small size of jewelry and quickly moved to larger objects. Washington state's most eccentric and controversial (one-term) governor is honored in this kinetic piece. When the rabbit's foot is pulled, the silver French poodle pet wags its tail and the marine biologist-turned-politician shakes a vial of polluted water.

Later works like The Blemish (1985) limit metals to a hammered copper lace and depend even more upon allusions to self-taught artists. More than her brother who lived in Ellensburg between 1964 and 1972, Merrily and her art remain rooted in the comfy, homey, funky side of Ellensburg, its ramshackle wooden buildings, its cowtown atmosphere, its sleepy college town mentality. With cozy junk shops and abundant roadside attractions, Ellensburg is very conducive to quiet, private fantasy.

With Don Tompkins's return to New York in 1972, Ken Cory took over the metals program. A graduate of California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, Cory arrived with a Funk sensibility ready to be adapted - or violated. Before that, he had studied jewelry under Victor Moore at Pullman High School and continued at Washington State University in the same town, studying sculpture under George Laisner.

Cory chose subjects which were erotic, both feminine and masculine. The juxtapositions of rigid geometry and floppy organic forms repeated over and over in his jewelry are a clue to this, as are his choices of materials: plastic and leather; copper and silver; hammered and stamped or smooth surfaces. A pioneer in men's jewelry, Cory was strangely hermetic and withdrawn compared to Don Tompkins, his predecessor. At the time of Cory's death, virtually his complete output was contained in a few compartmentalized suitcases. A full-scale retrospective and catalog are planned.

Again and again, Cory went far beyond the witty illustrations in his collaborations with Les LePere, the other Pencil Brother. The C.W.U. professor evolved an erotic vocabulary of male imagery: phalluses, auto parts, urinal traps, spark plugs, and batteries. These were executed in exquisitely intricate feminine techniques, however, like champlevé and cloisonné enamels (Nancy's Buckle, 1978). A late work like Tent Brooch (1988) retains all the mystery of Ellensburg Funky (insect? switch? vagina?) yet demonstrates a refined feeling for silver stamping, gold accents, and a single carnelian stone.

In 1974, 1975, and, 1984, Professor Cory organized jewelry shows on campus so that budding talents like Worden could see first-hand the best work being done nationally. Among artists included were Jim Cotter, Lane Coulter, Richard Mawdsley, Gary Noffke, Linda Ross, and J. Fred Woell.

Worden decided to go to the University of Georgia to study with Noffke after working under Cory, but Cory's influence has stayed with her. Though she would possibly deny it, her work, too, falls under the rubric of Ellensburg Funky. After all, what else could one call using a toilet bowl brush in a brooch?

Worden took to heart the loose or informal construction of Noffke, added an anti-preciousness of materials, and combined them (in ways Merrily Tompkins did not) with feminine subjects. Grateful for Cory's inspiration in the same way Merrily was indebted to her big brother, Worden commented in a letter:

What Ken created for me was an atmosphere completely lacking in pretense or convention… Without inhibition, his imagery wallows in what a lot of men like: sex, cars, tools, being outside and getting dirty… My work looks like an American woman designed it and I want it to.

Her Initiation Necklace (1977) with its mixing of plastic pink hair curlers, chicken bones, and copper and silver wire satirizes the tribal conformity of mall life. In that and other necklaces and brooches, Worden affectionately spoofs American rituals of beauty, mating, consuming. shopping, and romance.

Beginning her signature eyeglass-lens pieces in 1987, Worden created a series of pins both accentuating the roots of Ellensburg Funky - found objects, mixture of good and bad materials, informality of construction, and bizarre or sexual subjects - and added a crucial yet important factor: personal narrative. Acute, arcane, and rich, it is the hermetic narratives in West Coast art which is most maddening to East Coast residents, who view these artworks as self-indulgent, sell-referential, and, hence, shallow and narcissistic.

Worden's later necklaces like Broken Promises (1992), which use U.S. currency images of politicians in a mock-Victorian necklace, extend the cynical, inside humor of the tiny college campus to the wider social world. Her Seven Deadly Sins (1994) touches on current events even more and distantly echoes Tompkins's Commemorative Medals series.

Each of the seven sins - lust, gluttony, sloth, envy, avarice, wrath, and greed - is matched with a photograph (on the back of each metal section) of a prominent culpable celebrity respectively, Woody Allen, Elvis Presley, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Bo Derek, Leona Helmsley, Lorena Bobbit, and Imelda Marcos.

Finally, Ed Wicklander, another artist who took Ellensburg Funky further, into pedestal and free-standing mixed-media sculpture, had some salutary and insightful comments about the cowtown/college town phenomenon:

Their sensitivity dealt with personal narratives in a three-D realm. Nor only [Robert] Arneson, [William T.] Wiley, and [Robert] Hudson, but there were other influences there like Chicago artists H.C. Westermann, Jim Nutt, and Ed Paschke, along with giants like Kienholz and Duchamp.

My Dad's Foundry Pin (1976) could not get much more personal. Using his lather's Tacoma factory ID card, Wicklander fetishized a personal icon in close emulation of Cory. With a cast-silver crucible and silver-soldered copper and slate bricks, the foundry kiln is invoked and like the back of many Ellensburg metals, the reverse side is also deeply symbolic and visible. It shows his lather's fingerprint.

Nearly twenty years later, Bile Torso (1992) blows up the intimate joining of Cory's and Worden's brooches into welded-steel sections comprising a headless human figure. Building perhaps on the Surrealist-inspired years of his graduate work at University of Illinois - Champaign-Urbana, Bile Torso nevertheless harks back to little Funkytown in eastern Washington state. Wicklander demonstrates how often, in Northwest metals, big things start out in small packages, small, enigmatic, and funny packages.

Matthew Kangas, independent Seattle art critic and curator, writes frequently on crafts.

NOTES

Peter Selz, "Notes on Funk," Art in a Turbulent Era. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI

Research Press, 1985, pp. 325-330.

Ibid.

Nancy Worden, interview with author, April 9, 1994.

For example: R.E. Beans, Art Detective, Mike Holmes, Gary Green, Jimmy Jet, Charlie King, Marty Lovens, Jeanette Papadopolous, and Larry Reid.

Donald Paul Tompkins, "Crafts, the High Arts, and Education." Dissertation for Doctorate of Education degree, Columbia University Teachers College, New York, 1973.

Worden interview.

Ed Wicklander, interview with author, May 28, 1994.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.