Elsa Freund on Elsaramic Jewelry

3 Minute Read

We are often drawn to the naïve sensibility of self-taught artists in any medium. The fresh, unassuming quality of their work provides an antidote to a pervasive slickness of our highly technological society. Here, Bob Ebendorf recalls with pleasure his long-term friendship with Elsa Freuned, who fused glass on clay jewelry as early as 1950 and who continues today to be thrilled by the process.

In Elsa Freund's studio, there are several long tables filled with cigar boxes and paper cups, which, in turn, are filled with pieces of colored glass. Each piece of glass, combined with some native Ozark red clay, will eventually become a part of a ring, bracelet or neckpiece.

Elsa Freund did not have a jewelry background. She came to make jewelry in 1950 while teaching a design and craft class in the "learn-by-experiment" method. In one exercise, a variety of scrap materials were assembled into wearable items. This led to her experiments with clay and glass, and then to her so-called "woman-made" jewels.

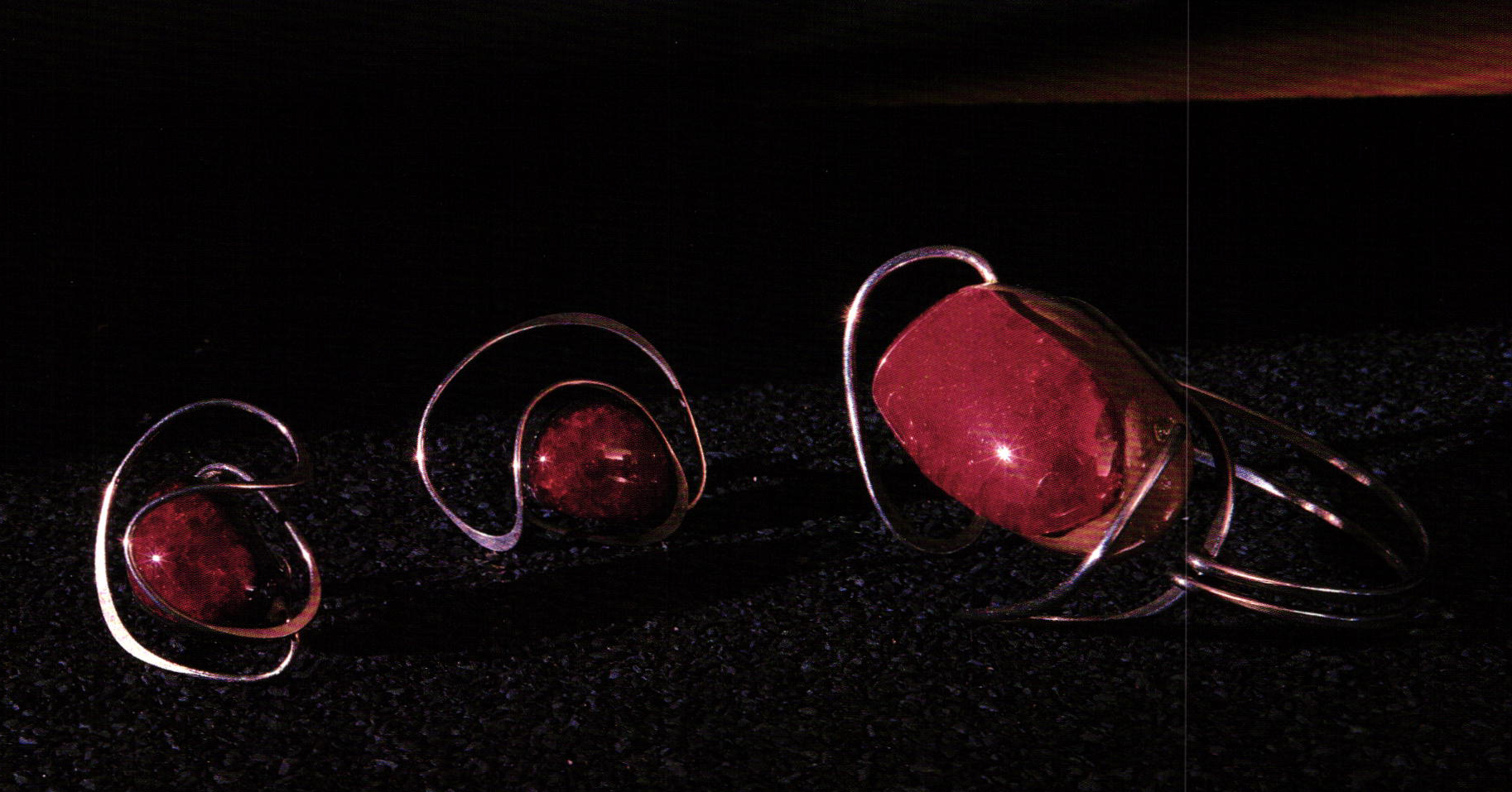

Elsa had developed her own color sense, having studied painting at the Kansas City Art Institute, at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center and Stetson University in Deland, Florida, but she didn't understand soldering. She would just work the silver wire with a hammer and a few hand tools. The hammer would produce thick and thin lines, which she augmented with gluing and cold connections, thereby finding ways of putting her design ideas together without having to learn sophisticated techniques. She would work the metal intuitively, then later read about the process. She would try again, look at other jewelry and in this way develop the rudiments of craft. Often she would come up with amusing solutions. For instance, she would use glue to attach pinbacks and then cover the glue with foil to add dimensionality.

She forged wire, working it into design relationships, then adorned the ends of the wire with jewel-like colors in glass and clay. At the time, in the 60s, there may have been ceramic people working in this way, but I did not know of other jewelers who were making these kinds of forms. She would make a simple clay form pad, open a hole in for the silver wire, then lay a piece of glass in the pad to be fired in her small enamel kiln. After it had cooled, she would assemble the piece by hammering and bending the wire to accommodate the "jewel"; the last step was to glue the wire in the hole.

Elsa was not a nationally recognized jeweler. She sent work to one national exhibition "The Art of Personal Adornment," at the American Craft Museum in 1965. Her piece was a tiara made of silver wire, forged, with fused glass and ceramic stones. However, her work was in demand regionally in the South, sold to friends by word of mouth. Most of the women in town had a few pieces. The Mint Museum in Charlotte, NC, purchased a piece for their permanent collection. In the early 60s, Elsa helped start the Florida Craftsmen's Organization, becoming sort of the spiritual leader.

I can recall going to visit her with my mother - even though we were very good friends, it was like attending a formal tea. You would go for an afternoon or evening visit, sit, talk, drink your tea, eat homemade pie or cake. Then, you would be shown her jewelry collection of brooches, necklaces, earrings, rings, buttons, bracelets, and, of course, the one she was working on. She would even show you her watercolors that sparked ideas for jewelry. It was a total experience and we would not go away without buying two or three things. The price of the jewelry was modest, yet to experience Elsa's style as a person and as an artist who loved her work was worth a lot more.

For much of her career, Elsa Freund worked late into the evening, as her husband prepared his art history lecture for the next day's class. They were both fulltime artists, he a painter. But Elsa never worried about what was "hot" or the kind of work that was being shown in the museums or galleries. She was more interested in making jewelry that you could use and enjoy wearing every day.

Robert Ebendorf, formerly Professor of Metalsmithing I Jewelry at SUNY, New Paltz, is now an independent jeweler in Santa Monica, CA.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.