The Enamelwork of Bill Helwig

12 Minute Read

When enamelist Bill Helwig celebrated the half-century mark in July of 1988, his wife Lenore Davis, asked the celebrants to festoon the trees with colorful paper strips with famous Helwig quotes. Most were culled from his workshops and provide a familiar litany for those who have experienced his teaching style over the past 20 years.

"What I say today is a lie tomorrow"- Bill Helwig

The quote above leaped to the fore as I reviewed my taped interviews with him, for, although I've know Bill Helwig for close to 30 years, he has remained an enigma. The hours of conversation for this article helped illuminate but certainly did not eliminate all of the mysteries.

"What I say today is a lie tomorrow" means that he is a consummate researcher and experimenter who continually reinvents and reintroduces technical knowledge to spur the growth of enameling as a viable exciting art medium. The ultimate enameling book, which we hope he completes and leaves as a legacy, may never reach the printer. Each day he discovers anew the wonders of glass fused to metal, and each night he rewrites the previous chapter. It has become a Penelope-like ritual.

Just where did the impetus for this enamelist's insatiable curiosity begin? The roots are Kansan and reveal much about the man. Raised by his grandparents, he asserts that his questions were either patiently answered or that solutions were suggested for the problems he posed. At six, for example, Helwig recalled being upset that he didn't have a bowl of his own, required for his play. His grandfather found some limestone pieces, and showed him how to rotate them over round stones to grind out two shallow bowls, warning the boy that it would "take some time."

This self-dependency mode was further encouraged during the family's thrice-weekly treks to the bowling alley, where he was given lots of paper and crayons to amuse himself. Early on, he could draw, or reproduce, virtually anything he saw. He claims, with a hint of pride, and no apology, that he's doing nothing different now than he did as a child in Kansas, exploring sandstone, mineral deposits, the residue of shell forms and a horizon uninterrupted by fences.

School itself was a less positive experience, including the threat of failure in the second grade just because he broke his crayons while trying to fit them into a more pleasing box. Helwig learned easily and quickly by observation and example despite his slight problems with reading, or with grasping words as total units. Very little formal art training was available to him, but during the summer following high school he took drawing and watercolor classes in a neighboring town while preparing to enter Fort Hays, Kansas State College as a Pre-Med student.

Helwig realized by the time he reached the junior year in college that finances and family attitudes would deter him from completing a medical degree, so he transferred to art. Two influential teachers John Thornes (jewelry and design) and Joel Moss (ceramics and watercolor) urged him to be excited about learning. Never idle, he created cartoons for campus publications, worked in both the bookstore and reference library and sold a lot of silver jewelry—examples of which he wishes he still had, due to their unique, avant-garde qualities. He remained at Fort Hays to complete both bachelor and master degrees in watercolor, with thesis work that was abstract, vigorous and freely handled.

After graduation, in 1961, he taught junior high school art for one semester in Leavenworth, Kansas, then headed south for a Mexican holiday. But a draft notice intervened, and Helwig enlisted in the Army. Due to a fluke he was sent to Wurzburg, Germany, for a 30-month assignment, winding up an Administrative Specialist at the post's hospital (when they learned he could type) and enjoying some freedoms that few other enlisted men could manage. Not content to merely "serve his time," Helwig ran a radio station, designed Christmas cards and medallions, painted, worked with Special Services and arranged children's programs.

Upon discharge he returned home to become the assistant director of the Creative Craft Center at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he remained for nine years. Jean Delius, who had seen Helwigs watercolors, suggested that he might like enameling, and the first seed was sown. Within three years, he taught himself the basics, beginning with color-field studies, which employed fire scale and bands of color. He read voraciously and turned his attention to grisaille since there was little or no competition in that area. Margarete Seeler provided encouragement and information, but the remainder he acquired through autodidactic tenacity.

Marriage to fiber artist Lenore Davis in 1968 enhanced both his interaction with the art community and his own creative energies. Early Helwig grisailles suggest interesting parallels to Davis's use of the human figure as landscape. Both grew up in the flatlands (Kansas and Montana), with similar spatial landscapes of interminable blue skies and unbroken horizons. As an independent, solitary child, Helwig seems to have later suffused his enamels with mythical figures from his reading, or with surrogate friends from his imagination as a way of counteracting that endless Kansan plain. Davis, the daughter of a forestry professor, used her ebullient figures to form the landscape and to protect its riches, ever mindful of the freedom such spaces provide. She seems to find the spaces liberating; he tends to find them restricting.

By 1973, Helwig was teaching part-time at Buffalo State, but there's no doubt it was a full-time effort. As he says, "I know I teach very well; I had very good teachers." Disciplined and demanding of himself, he expects the same from students. He might have remained in the academic realm, but was lured by Woodrow Carpenter to the Ceramic Coating Company in Newport, Kentucky in 1977, to head the Vitrearc division. These two men shared knowledge about, and enthusiasm for enamels, resulting in an eight-year commitment by Helwig to the development of lead-free enamels for artists. This was the period of his greatest technical growth: testing and changing formulas, researching historical documents and tying everything together with current industrial methods.

The laboratory at Ceramic Coating Company became his studio. It wasn't uncommon for him to fire 144 one inch text squares five times in one day, in addition to his personal experiments (he was free to create his own imagery) Helwig mastered the techniques as few others could, developing an inner clock for firing times and silting enamels with astounding accuracy and consistency. He learned the language of industry, to communicate with the production team, and edited the publication Glass on Metal Unfortunately the intensity and success of these efforts also precluded participation in juried shows or the wider dissemination of his enamel work.

Helwig admits that he became locked into discovering—a virtual victim of information. His industry, experience may have heightened the conflict between scientist and artist, with the prolific edging out the profound. Although he prepared pieces at home to fire at the factory, this period of intense production necessarily resulted in some schematic work. The enamels completed during this stage seem, despite their technical virtuosity, to be more contrived conceptually, no doubt due to the stress of relentless research.

Thus, in 1985, he decided to become a full-time studio artist. He refers to himself as an alchemist who retires to his monastery, gets out his enamels and plays. His third-floor studio is relatively free of visual stimuli or music. Helwig works on six to eight enamels simultaneously, some of which require only a few hours and a minimal number of firings, others remaining in the studio a year until they're considered finished. Unlike many enamelists, he seldom draws or plans pieces in advance, preferring to approach the metal like a painter does the raw canvas.

Since even his kiln can provide surprises when colors layer and interact, some firings lead to extended contemplation and reworking. Nor do transparent enamels allow the luxury of completely obscuring an area to begin anew as pigments can. As a watercolorist, he is accustomed to spontaneous, direct application methods, but the kiln adds another factor to the work's success.

Helwig's impact on enameling has been profound. He has either "reinvented" or brought back numerous processes and techniques through tireless research and experimentation. First on his list of contributions is the grisaille technique which he presented in larger formats and with contemporary imagery. Coupled with his growing expertise in grisaille enamel, he reintroduced the art of fuming, as practiced in the Tiffany and Lalique studios, to create lustrous, iridescent surfaces with myriad color shifts. He consulted with glass artists and chemists in developing his own method.

The process also made him ill, so it was removed from his repertoire. In defiance of the conventional stamped metal forms available to enamelists, he innovatively altered the outside edges, pierced interiors, hammered plates full of texture, upturned edges or manipulated the metal while still hot from the kiln. The latter process was new in America but had been practiced in Europe for years. Like so many of his discoveries, what began as an accident emerged as yet another method to push enameling beyond the limitations often ascribed to the medium.

When asked why he ignores or dislikes cloisonné enamel, he responded that he prefers to leave it to others who do it well, and that he "doesn't like fences." The shoe series, which he created as a teaching aid several years ago (Double-Breasted Boot) resulted in cryptic social comments about shoes and their wearers and allowed his sardonic wit to emerge in the titles. He saw the work as being nonserious, therefore the humor and sarcasm were given free reign, and the results often delight. I think that his avoidance of cloisonne is two-fold. When he first began to study enamels, he realized that the field was crowded with cloisonné artists, and he wanted to carve a totally unique niche for himself that could lead to greater recognition. In addition, the wires tend to impede his painterly approach to the medium, drawing too much attention away from the rich colors, depth and surfaces he desires.

Preferring direct, spontaneous methods of enamel application, and a pastiche of processes, he relied upon the shallow bowl format for years. He feels that the manageable size and shape allow the viewer a personal interaction that comes with turning the pieces in the hand. I fear that this assertion forestalls consideration of the real problem, that of presentation. It is difficult to imagine these expensive enamels piled with food, despite Helwig's claim that he prefers that functional aspect. Rather, I see the pieces deserving special presentation, either on the wall or in boxes, to isolate them in the environment. Helwig is aware of the presentation problems, particularly with the shallow-bowl forms, but no affordable, acceptable solution has been found.

He even began to make his own glass, resulting in some unique ruby and pink colors. Also, rather than using the lusters commercially available to the enamelist, he tried Winsor-Newton's pure gold on the surface, firing it in place with the addition of oil binders. Red Sea, She Said uses underglaze ceramics pencils in a new way as color tonalities and line work atop enamels. These experiments occurred nearly 15 years ago and are now taken for granted by the enamel community.

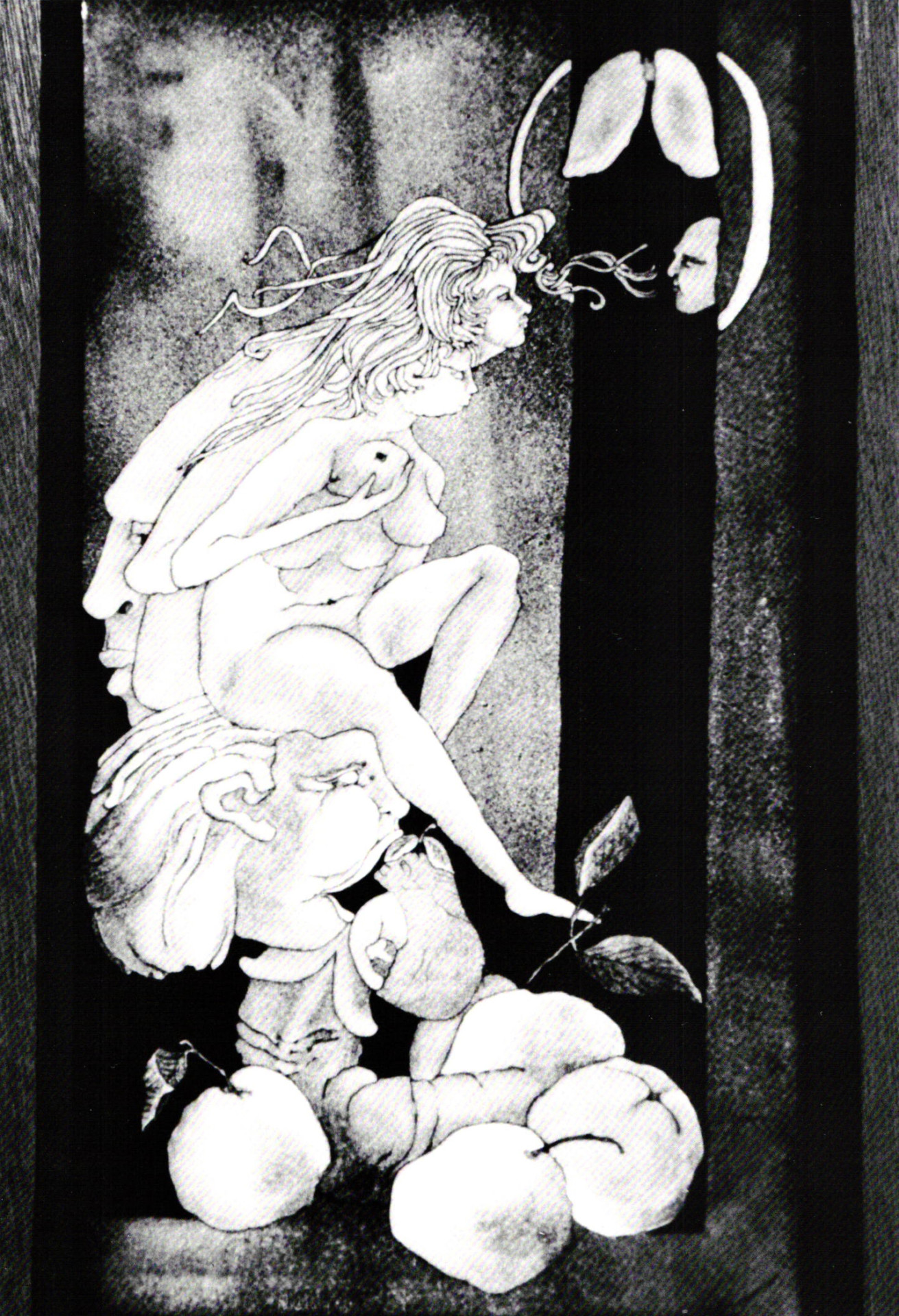

Discontent with using minute amounts of silver or gold foil to accent an enamel, Helwig covered the entire surface, then reticulated details or used oxides to create his imagery. A Helwig signature style is the hiding of bodies within bodies or faces within heads, like the games included in the Sunday comics that he remembers from his childhood. Unafraid to alter the surface, he will etch it chemically, add oxides and fire anew. If a sculpted surface is the goal, enamel is applied like an impasto painting.

There are no sacred cows in Helwig's enamel lexicon. He's an enthusiastic, prolific risk-taker in the enamel studio, and his expertise is unmatched. Fortunately, his selflessness provides for the promulgation of that expertise through his workshops and writings. He encourages students to learn the logic of the process, rather than the process itself. Helwig generously shares his hard-earned technical knowledge to assure progress in the medium. Unencumbered by an academic's strictures, he reinvents the art form daily, both technically and esthetically.

When you become aware of the thousands of enamels he has created, it is easy to forget that Helwig has been involved with the medium only since the 1960s, and that a considerable portion of that time was spent teaching himself or working closely with manufactory. Thus, his image making may still be in its infancy. He concurs that his images will change and become more personal the longer he is away from industry. I sense that the close, introspective scrutiny that he lavishes on these pieces during their production can lead to a surfeit of both technique and imagery, resulting in a less cohesive whole.

A close-up, for example of Alpha-Omega reveals the strength and intrigue of one surface and could stand as a statement unto itself. The figurative, narrative works, although readily identified as Helwig's, are often inscrutable. In some works, the figures are stiff, with bizarre exaggerations, and a whiteness that makes them float eerily above rich fields of color. I respond most favorably to the works in which figures are shrouded or suggestive. for when Helwig gives me less, I'm usually rewarded with more. They allow the viewer to move between figure and ground and encourage personal interpretation.

Moving away from the figurative, he is currently engaged in new work on larger steel plates, featuring bed sheets and pillows in various stages of disarray, as in Bed Sheets and Pillows #2, Inner Edges. The series is as free, fluid and provocative as the watercolors from his graduate school days. One cannot help but respond to their spontaneity, peacefulness and masterful handling of the diaphanous materials. During the course of the interviews for this article, Helwig admitted to being an elitist, and I would concur that the majority of his previous enamels convey that attitude.

The Bed Sheet series, however, provides yet another interpretation for his quote "What I say today is a lie tomorrow." for these works are not elite. They imbue the familiar trappings of everyday life with an aura of mystery yet avoid being overworked or unapproachable These pieces suggest to me a Bill Helwig who is more mellow and introspective yet communicative of personal feelings. Since his technical base is so secure, this seems an ideal time to allow his conceptual base to flourish. If this series is an indication, I will follow his journey with enthusiasm.

Beverly J. Semmens is a fiber artist and associate professor of fine arts at the University of Cincinnati.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.