Fads and Fallacies: Post Modern Collection

7 Minute Read

One of the heralded events in this year's ebb and flow of jewelry fashion was the arrival of the Cleto Munari Post Modern Collection: 160 pieces, designed by "name" Post Modern architects, produced at a cost estimated at a million dollars and packaged with its own ready made traveling exhibition, together with a deluxe promotional book.

Cleto Munari, a wealthy Italian industrialist and entrepreneur, had lofty aspirations for this project. As his publicity claims: "Munari's proposal is without commercial objectives but utilizing the custom and the friendly relationships of years of collaboration, he wishes to offer in a large exhibition a comparison of jewelry between the most interesting contemporary cultural tendencies and the best brains of a generation. All the jewelry that forms the exhibition has been made by hand by master craftsmen in gold and precious stones; the pieces are signed and numbered and all are destined to make history."

Munari's employment of "name" designers to "liven up" the appearance of a commodity like jewelry is not without precedent. Since the 1920s, manufacturers have utilized this approach with great success, applying seductive packages to everything from typewriters to coffee pots, the underlying theory being that style (as in, he has style!) mitigates between the ego gratification of the buyer and the object that materializes this desire. Style is what the consumer wants, and he/she will seek out products that carry the appropriate identification codes. This is neither new nor astonishing. The advertising world has lived by this scripture for quite some time, citing chapter and verse from tail-finned autos to tie-dyed t-shirts.

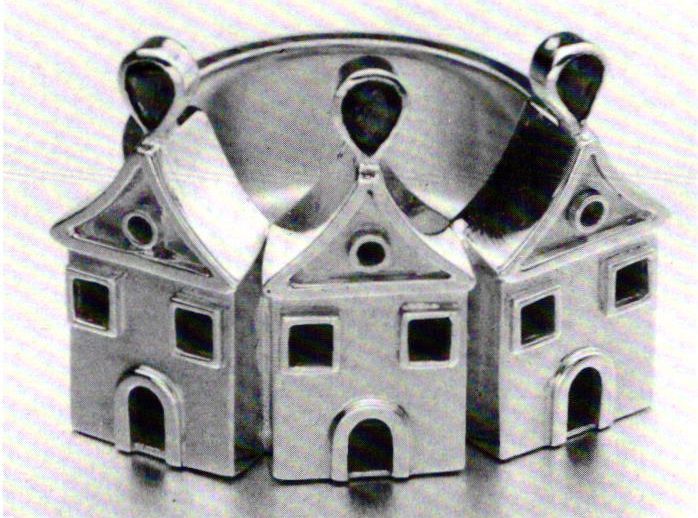

But does this fashionable code, as in the case of Munari's Post Modern collection, overshadow the "crafted" value of jewelry in material and method so long a part of its tradition? By their own admission, many of the architects have only a cursory knowledge of jewelry design and fabrication. Stanley Tigerman said, "When someone asks you to design, you design. It's a way of resting your ideas." Michael Graves admitted. "I don't know how to make jewelry," while Richard Meier said, "When Cleto asked me to design a ring, I thought, that's nice—I'll build a little building that someone can wear." The designers provided renderings or drawings, which were then worked into form by anonymous "craftsmen" or benchworkers. In some cases, the architects lack of technical knowledge took a toll on the craftsmen. Eisenman's fractured cube of 100 small rods "took us about a month to figure out how to make." according to Munari, while the craftsmen often had to make suggestions of appropriate stones to execute the formal visions of the designers.

The resultant jewelry thus reveals a disregard for, or ignorance of, the craftsman's esthetic. There seems to be no affinity for the workable properties of metal. Gems often appear to be applied merely for commercial value. The architects apparently could not think in small scale but rather truncated their architectural ideas in torturous fashion. In most cases, the wearer, psychologically or physically, is conspicuously absent from the designer's program.

The concepts? Considered as small sculptures, the pieces sit like wilting maquettes begging for execution. and as jewelry they appear like ostentatious hood ornaments whose only purpose is to awkwardly personify the marque of the maker.

It appears that neither Munari nor his designer's had any pretentions beyond propagating the label syndrome. To appreciate jewelry as craft, one must appreciate values in material, method, function and form, but to appreciate fashion, one must only know the cultural code. Unfamiliar with the code? You can rest assured that the label validates your choices. Ralph Lauren guarantees it; Michael Graves guarantees it. For this reason, the Cleto Munari Collection must be viewed as fashion. It was the label that he was after—the label and the stylish "look" of Post Modern architecture. Although Munari would probably prefer the stamp of "fine jewelry." since he has invested the collection with so much material value, he has opted for the approach that says there are better ways to buy jewels but there might not be a better way to buy certified "Post Modernism to wear."

The question then is if sttle can be divorced from craft: Does it have value in and of itself, and can jewelry be successful through style alone? Munari was obviously after the blanket coverage that style with a capital S affords, in this case the Post Modern Style. However, the individual pieces are anonymous as to the hand of the maker/artist. In neither design nor gesture is there a particular manner characteristic of a person, group or period. There are no apparent physical clues that might distinguish these works within the historical continuum of jewelry. As to these architects' concept of jewelry, the interview questions in the book stoop to the banal. "What kind of woman did you have in mind when you designed your jewelry? What woman do you fantasize wearing them? Do you like buying jewelry for a woman? If a piece of jewelry could be made a symbol of power, eroticism, seduction or magic, which would you be inclined to choose?" There is little here to inform our appreciation. Consequently, the Munari Collection is more stylish than it is evidence of a new Style.

The pieces borrow the signature motifs: vaults, pyramids, stepped arches, temples, keystones, etc. that are reminders of the Post Modern architects' work nonjewelry media. They are like dime-store souvenirs that encourage our memory of experiencing the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building. Nevertheless, because of our fickle culture, the Statue of Liberty is kitsch while Post Modern pavilions are chic. When we look at the jewelry, our attention is diverted away from the jewelry itself and toward the architecture it symbolizes. The craft dissolves into the code of the symbol, just like the comfort of jeans is obfuscated by the Calvin Klein label or the smell of the perfume is diffused by the aura of Yves St. Laurent. These designers are capitalizing on the overwhelming power of the stylish that embraces a broad territory, from architecture to clothing to accessories. Today, fashionable does not only mean being "clothed in style" but also being surrounded by the appropriately labeled sheets, perfume, furniture, cars, dinnerware and jewelry.

Regardless of the misguided attempts of Munari's architects, there is merit in evoking style for both the maker and the public. Munari was half-right when he hoped that his collection would be a comparison of jewelry between the most interesting cultural tendencies and the best brains of a generation. Fashion, the decorative arts and crafts, which are slowly becoming synonymous, have their roots in the spirit of an age, defining and affirming the vernacular of material culture. Whether you consider the Art Deco or Art Nouveau Style in decorative arts or the Punk Style or Belle Epoque in fashion, style functions successfully to pattern our response to a lifestyle that needs to be enhanced by what we wear and what we use. The investigation and interpretation of a broad cultural spirit is no less valid than the individual investigations of fine artists seeking answers to life through reflection.

The problem with the Munari Collection and all other "label" manifestations of stylish fashion is not in their intent but in their methodology. Instead of seeking the vernacular through evolution of vocabulary and form inherent in the jewelry medium, they opt to apply the slang of a foreign tongue. Their actions deny the potential of the jeweler to evince his own answer to the Post Modern condition in favor of reinforcing the architect's solution. Although "structure" and "building" are part of the language of jewelry, these architects render jewelry as a facile vehicle for self-promotion. Like three-dimensional "autographs," their value rises and falls with the fame and notoriety of the author. It leads inevitably to having their architectural motifs emblazoned on t-shirts, perfume bottles or jeans. Whether the nomenclature of Post Modern jewelry will prevail depends on whether it is surpassed by a more current label that captures the imagination of the fashion press.

In the case at hand, sole blame is not shouldered by the Munari Collection for debasing the value of jewelry as merely stylish. The Munari Collection is spotlighted because there is no apparent leadership among jewelers. The plethora of fashion jewelry being produced continues to revive past epochs, e.g., Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Primitive, Classical. In fashion, jewelry is still an accessory. It is only a matter of time before fashion designers "label" jewelry like perfume and underwear to extend their hegemony over the entire market. The answer to the Munari Collection is not to ignore the challenge but to address the mantle of leadership, to develop in form and content a contemporary style that will not only capture the imagination of the public but also affirm the credibility of the jewelry as the focal point of style.

Ciao.

A. Stiletto works in and around New York and writes a regular column on fashion.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.