Fads and Fallacies: Surrealism in Jewelry

5 Minute Read

While Surrealism has had a major impact on how we look at 20th-century art, the same cannot be said for its impact on 20th-century dress. The costumes reflected in the paintings and photographs of the 30s and 40s appear to be merely capricious attempts to rattle the authority of propriety and decorum. They seem to subvert rather than uphold the myth of a complimentary self-image that is the basis for success in fashion. However, Richard Martin's recent exhibition "Fashion and Surrealism," and the accompanying catalog, finds value in these costumes' playful indulgence and perverse illusion.

By offering an interpretation that relies on line art as well as fashion, he elevates the Surrealist costume to a position of therapeutic importance. Martin encourages us to reexamine the Surrealist experiments of disparate designers, from Karl Lagerfeld to Adelle Lutz, as efforts to liberate our natural instincts from clothing's social straightjacket.

Through his didactic installation, Martin reveals the power of projection not only in fashion tableaus bur also in photography, advertisements, painting—in all visual media that communicate cultural values. Once we realize that our self-image is sublimated in an illusion contrived by fashion or cultural prognosticators, the Surrealist use of Freudian dichotomies, of alienation and reinforcement becomes clear.

The friction between the ordinary and the extraordinary, disfigurement in contrast to embellishment, the physical body and the concept of the body, optical truth and dreamed doppelganger implicates fashion as the mirror of vanity. Martin suggests that fashion's attraction is based on an awareness of clothing as the metaphor, metamorphosis and metaphysics of man—"allowing us to understand the contents of work by what we know intellectually." The illusionism and conceits of the eye offered by Surrealist costume conceal and at the same time reveal the marvelous in the mundane world, the dichotomy of inner reality reflected by external dress.

My disappointment with this otherwise illuminating exhibition lies with the apparent oversight in regard to Surrealist jewelry. Much has been made of Dali's collaboration with Elsa Schiaparelli, but little recognition has been paid to modern jewelers who feed on the spirit of Surrealism as do their counterparts in dress. More importantly, Martin's exposition of the Surrealist metaphor in language and imagery could have been just as easily applied to the role of jewelry as symbolic ornament.

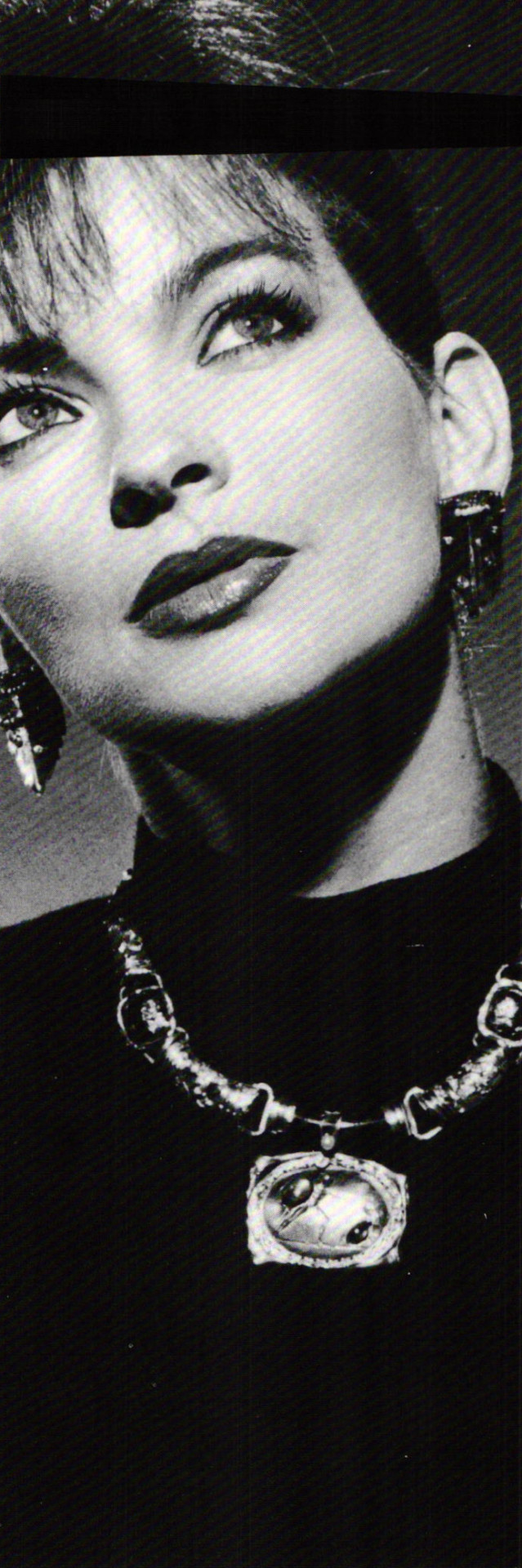

Walking through the exhibition, mindful of Martin's stylistic schema: the bodies and dismembered parts, displacements and illusions, the ambiguity between the natural and unnatural worlds. I anticipated seeing contemporary jewelry that reaffirms the Surrealists' power: the biomorphic shapes and erotic body distortions in the work of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum, the hand bracelets of Bruno Martinazzi, the eyes of Mark Jordan, the torsos of Barry Merritt. The conceits of the eye that reveal and conceal are powerfully represented by Caroline Broadhead's monofilament veils. The disruption of customary associations is fancifully employed by Wilhelm Mattar's cleaver earpiece and Julia Mannheim's ladder necklaces. The juxtaposition of natural and unnatural imagery that probes the depth of ego informs a vast amount of contemporary jewelry from Ken Loebers fish pins, Stirling Clark's pasta necklace, Gijs Bakker's chrysanthemum collar to Otto Kunzli's brick brooch and Catherine Riley's felt maggot beads.

In retrospect, jewelry is a uniquely appropriate Surrealist carrier. since it embodies meaning through association rather than through the physical transformation necessitated by clothing. Surrealism, which favors the optical qualities of dress, has a direct referent in jewelry as a visual art, whose language communicates on the surface of the costume, on the patina of our self-styled image. In effect, jewelry as ethereal and ephemeral "accessory," satisfies the Surrealist's desire for an artifice in whose isolation they would find clues of the subconscious—the goal of metaphor to find meaning somewhere outside itself.

The Surrealist's compression of clothing and artistic forms into the concrete sign of femininity correlates the world of real objects with the illusions of the mind. In this, jewelry's traditional role as communication of female assets finds further correspondence. The Surrealist fascination with mannequins as surrogate idols adorned with symbols of wealth and status translates into the jeweler's approach to the body as a pedestal for metaphysical messages. The Surrealist use of a hat, shoe or glove as a synechdoche for the psyche is analogous to the jewelers diminuitive compositions that paraphrase personality. The trenchant use of Freudian symbolism is not far removed from the jeweler's peculiar rendition of ritual and romantic sentiment. All in all, the objectification of an inner reality is a major impetus for the creation of jewelry and satisfies the goal of Surrealism in its attempt to surpass conventional description by offering an analytical anatomy prescribed by the wearer's emotions.

While we are still in need of a comprehensive survey of Surrealist jewelry as Martin's show has done for dress, one thing is certain, the basic tenets of Surrealism, the repercussive content of their approach has no more proper milieu than in jewelry where mysticism and perversity, dream and reality, disruption and ornament commend its function. Where jewelry's history has found a place for Dali's fantasies, so, too, fashion history must find a place for jewelry's heros. If there is an attempt at revision, it must start with the pantheon. Where Martin has elevated the figure of Dali and Schiaparelli, I recommend we add a jester to the king and queen's throne—and there is no more likly candidate than Sam Kramer.

The book/catalog Fashion and Surrealism, written by Richard Martin, was published by Rizzoli International Publications. Inc., 597 Fifth Ave., NY. NY 10017 in hardcover and paperback, with 56 pages in color and 300 duotone illustrations. The exhibition "Fashion and Surrealism" opened in the fall of 1987 at Fashion Institute of Technology in New York and will travel in the summer of 1988 to the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

A. Stiletto works in and around New York and writes a regular column on fashion for Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.