The Form Beyond Function Exhibition

27 Minute Read

"Form Beyond Function" was organized by Kington and David Prince of the Mitchell Museum, Mt. Vernon, Illinois, in conjunction with the Society of North American Goldsmiths. The exhibition, comprising 52 works by 40 artists, is an attempt to explore sculpture within metalsmithing and, more importantly, to define metalsmithing's "modern" sensibility within the continuum of 20th-century fine art.

"This exhibition is the first assembled in the United States which features sculpture created by artists who have their roots in the metalcraft tradition." This proclamation by co-curator L. Brent Kington, Director of the School of Art, Southern Illinois University, calls our attention to an ambitious undertaking.

In the catalog foreword, Charles Thomas Butler, Executive Director of the Mitchell Museum, claims that "'Form Beyond Function' presents a new definition for metalsmithing . . . the telling factor where idea is primary and utilization is secondary." This apology for craft's function together with the sarcastic allusion to design's epithet "form follows function" in the title might be interpreted as the supplicating posture of the "minor" arts in their quest for equal rights. For many spectators, a cursory reading of this show might elicit suspicions of self-aggrandizement, of a contentious showcase of sculpture's affinities at the expense of a coherent metalsmithing foundation. However, a closer look at the work and its underlying postulates unveils a provocative yet respectful dialogue with both traditions.

The vast majority of metalsmiths represented here are in their 30s and 40s, approximately half are women and just about all have a degree from a university metals program. Made over the last three years, the pieces are sculptural in format, free-standing or relief (no suggestions of body adornment or holloware) and exclude the distracting influence of decorative stones, etc. that are pan of metalsmithing's "jeweler's" heritage. Curating was done through submissions, while "elders" John Marshall, Hekki Seppä, Brent Kington, Bob Ebendorf and Gene and Hiroko Pijanowski were seeded to suggest a legitimate parentage. Baring the inclusion of these live, a sign of insecurity in the need to validate through reputation, this group of metal sculptors limn a contemporary portrait of conceptual and formal affinities.

Before examining this portrait. We must consider the prefatory catalog essays as constructing the argument for a reappraisal of sculpture within the metalsmithing tradition. In "Transcending Tradition: Sculptural Issues in Contemporary Metalsmithing," David Prince fails to raise any "issues," summarizing instead the salient features of normative appreciation. Size, detail, material and skill are perfunctorily cited as attributes of metalsmithing, as they are, for that matter, attributes of all crafts. Concerned as Prince is with the suitability of the medium, the pro forma acceptance in the purview of the fine arts, he neglects the craftsman's obvious technical proclivities and the effect these might have on the audience. He does not contend with the possibility that within a time-honored methodology, there might lie esthetic nuances of profound importance, e.g., the psychological effects of working in a "smaller' scale, the ability to forge meaning with the naive hand, the conflation of historical functionality and purely visual ends, the communication of emotional empathy in making. Without such an investigation, I believe, metalsmiths, and all craftsmen, will remain mired in the ontological thicket of their "own devices," left without hope for a critical esthetic. While Prince seems to recognize the undertow of metal's sculptural qualities, he is reluctant to explore the underlying virtues of its craft intentions, thus remaining entrenched in critical ignorance.

Instead, he ushers in the salubrious air of "pluralism" that has invigorated current art discourse. "Recently artists in general have shown an interest in appropriating elements from various historical styles and combining them into visual statements that either subvert or contradict original intentionality," he writes. "Metalsmithing and sculpture, therefore, are no longer isolated from each other. Artists from both areas are rejecting the definitions that have historically segregated them and the arts in general." Prince is offering a remedy for metalsmithing's cul de sac based on his reading of the pastiche that characterizes the "post-modern composition. He implies that the craftsman's recurring use of his own heritage as subject matter is akin to the line artist's use of art-historical references to buttress his content. Thus, the freedom to borrow art's artifice for art's sake, or craft's artifice for craft's sake or, ultimately, craft's artifice for art's sake liberates multifarious esthetic forms from the requirements of birthright and pedigree.

Although David Prince's prescription relies on a fortuitous break in the hegemony of the arts, Bruce Metcalf, Assistant Professor, Kent State University, appears more confident about a self-referential context for modern metalwork. A proponent of metalwork's sculptural authenticity, Metcalf offers a provocative argument in his essay "Outside the Mainstream": "Most of the work here is very much of our time and place. It's thoughtful, convincing and acknowledges the developments of 20th-century art. Most of the work in this exhibition is heir to the tradition of modern art but not necessarily to the associated intellectual programs." Metcalf appears to bring greater weight to bear on an incipient philosophy than on stylistic confluence. He sees the metalsmith's approach to his work as anathema to this century's dominant credo, what he calls "Modernism," which, I believe, he loosely interprets as a concern for overintellectualizing, cold, clinical theorizing and a dense metaphysical construct. Instead, according to Metcalf, metalsmithing's current direction, its form and function, is decidedly post-modern in its innate resolution to expurgate analytical sterility from the artworld's imposed vocabulary. For Metcalf, the development of both anomalous craftsmanship, "these artists have no choice but to work the way they do, as most of them have a sensibility about art that is not well represented in the modernist pantheon," and its corresponding empathy, "much of the work is intended to recreate an emotional state, to share some of the artist's enthusiasm with the audience," can lead in no other direction.

As a result, for both Metcalf and Prince, the time is ripe for a proper appreciation of sculptural metalsmithing. The current permissive climate that is cynical anti-modernist allows ostracized fields like metalsmithing to find their way into the current art dialogue. For them, it is not so much that metalsmithing has matured as an independent art form but that it represents a rupture in the art world's value system that demands attention. Both Metcalf and Prince do not consider that metalsmithing has evolved through various formative periods that might include Modernism; instead, they focus on sculpture's current fascination with material, process and scale to lend credibility to metalsmithing's historical values. Their posture is one of petitioning external auditors rather than championing inherent assets.

"Form Beyond Function" fortuitously coincided with the landmark exhibition "What is Modern Sculpture?" at the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris, a massive assembly, spanning the first 70 years of the century, of seminal works by Brancusi, Giacometti, Picasso, Gonzalez, David Smith and others. Unlike "Form Beyond Function," the curatorial approach of the Pompidou exhibition betrays an orthodox "Modernist" point of view. Curator Margit Rowell believes that 20th-century sculpture separates itself from the past through a shift from perceptual work to conceptual work, the latter being antidescriptive and antinarrative and based on rupture rather than continuity, she describes two resultant esthetics: the esthetic of culture—analytical and theoretical, Futurism, Minimalism—and the esthetic of nature—myth, psyche and the search for human forms and truths. The efficacy of Rowell's approach resides in the attempt to reconcile the revolutionary concept of Modernism with the evolutionary appearance of its attendant forms. The visible language of Modernism has not only become a working syntax for the way we have seen all sculpture subsequently, but its influence has also extended to the way we see all sculpture of previous epochs. However, the relevancy of its fervent world view and intractable theories has come under attack as the century comes to a close. It is ideology, not form nor content, that is in question.

Where "What is Modern Sculpture?" avails the art world with a test of Modernism as a conceptual influence on sculpture, "Form Beyond Function" ironically tests metalsmithing's ability to accommodate a contemporary sculptural appearance. Where sculpture is looking for conceptual paradigms, metalsmithing is looking for formal paradigms. Both shows, nevertheless, embrace history, a commiserating history that at times languishes in the penumbra of hierarchical forms. For sculpture it's painting; for metalsmithing it's sculpture. Yet, both fields maintain a stubborn defence of their individual traditions. For, as Gary Griffin, Head of Metalsmithing at Cranbrook Academy of Art. has concluded in his essay. "I readily admit to the influence of the greater arts context on the works of contemporary metalsmiths. However, I do so with the awareness that while the disciplines interface, they carry a specific history. Without a sensitive awareness of the historic lineage of a discipline together with consideration of the greater visual and context, understanding and evaluation of Metalsmiths Making Sculpture ["Form Beyond Function"] can only be viewed as shallow."

There are few differences in form between metalsmithing and sculpture, yet there is a noticeable difference in the way they function. My intention is not to distinguish metalsmithing from sculpture, nor to provide a laundry list of esthetic concerns, as these change as last as one can catalog them. Instead, I propose to look at the work at hand cognizant of the apparent difference in the metalsmith's point of view.

The metal sheet as sculptural plane is of particular fascination to this generation of metalsmiths, as exploration of edge, graphic imagery, painterly gesture and surface texture predominate in their work. While for enamelists the cosmetic surface has become a successful vehicle for painterly expression, for sculptural metalsmiths the formal interrelationships of painting and sculpture have not been resolved. They appear confounded by scale, perspective, the limits of context and the expressive use of color. They are caught between the valued distinctions of these devices in fine art and the lack of them in metalsmithing, where color, form, texture and context are wedded to material malleability.

In "Form Beyond Function," the work of Martha Banyas and Bruce Metcalf shows signs of accommodating metal's graphic plane with sculpture's ambient space. Banyas's Will Be, Is and Was positions three variant masks in a disjunctive perspective, one behind the other, thereby extending into three dimensions the cubist innovation of multiple views in a single plane. From the side, the composition disappears; from the front there is only a hint of what lurks behind, while at an oblique angle, all three masks are in view. Although Banyas uses the spatio-temporal effects of sculpture in the round, the composition retains its planar identity, a virtual layering in space. The torn edges of the copper skin not only scribe the profile and eyelets but also provide a break in the surface that windows the masks behind.

This incompleteness of perspective is intensified by the brutalized plane of the foreground mask. Its truncated silhouette delimits a static framing, implying that the superficial image extends its artifice to various deeper levels of the composition. Its psychological content portrays the progressive layers of personality as flat images. These masks exist only temporarily as formative stages. comprehended by the tour-de-force rendering of psychological depth in literal depth of perspective.

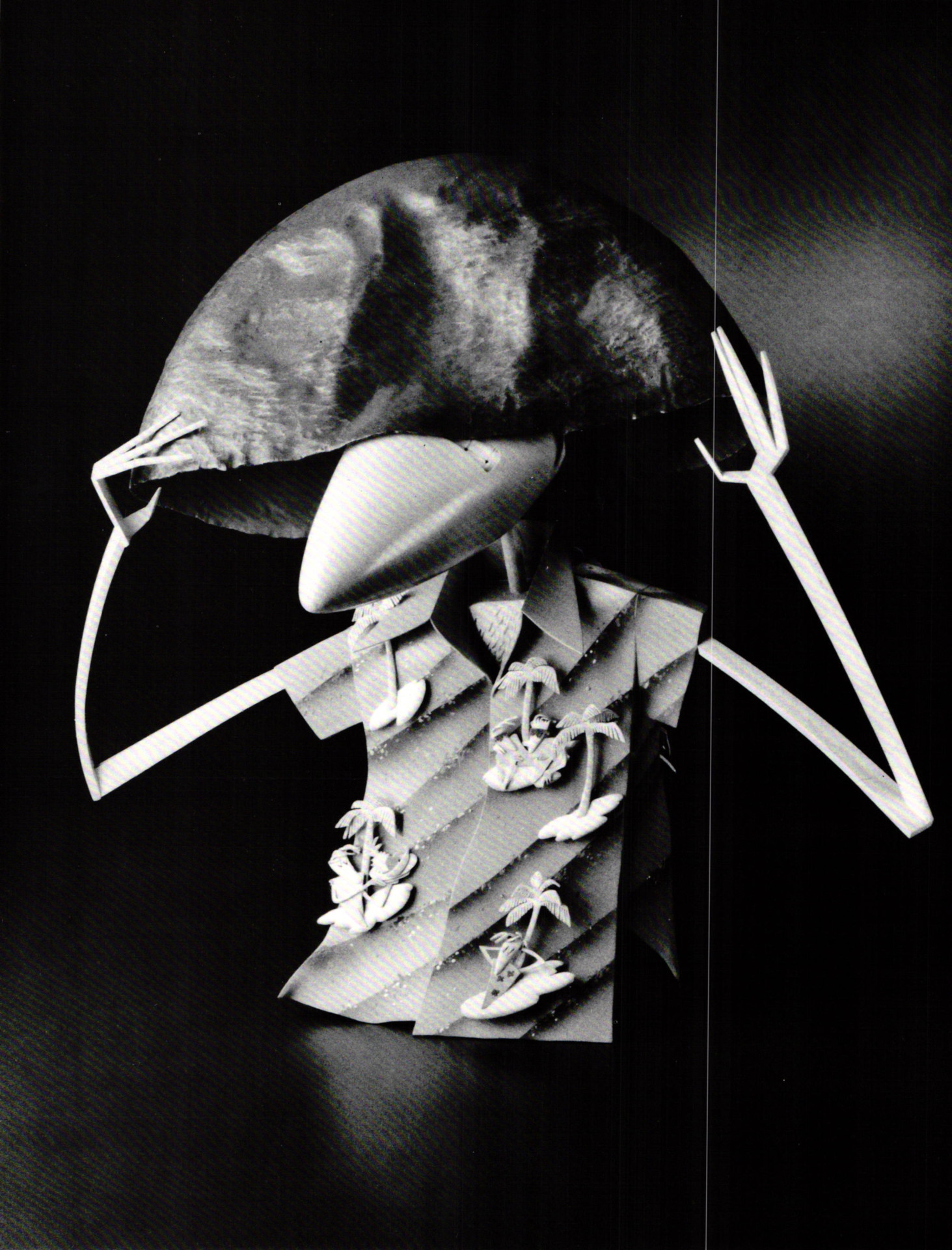

Nice Shirt, but His Head is in a Strange Place, Bruce Metcalf's portrait, appears to be graphic illustration. His work is replete with literal allusions to visual illusions and, in effect, is, like wearing 3D glasses at a "B" movie. The title calls our attention to the facade of Hawaiian-shirt landscapes, aka, relief work, as indictments of a historical preoccupation with gratuitous embellishment. It's a nice shirt, pleasing, but trivial. The irreverent metaphors continue as the pointed chin, a symbol of ignorance, is blinded by the oversize fool's cap, the hammered and hackneyed holloware vessel. The vessel of tradition, the vessel of knowledge in Metcalf's point of view becomes the burdensome icon that clouds rather than clarifies the artist's vision. These metaphors complement Metcalf's approach to sculptural irony. In rendering substance entirely optical and form pictorial within the same perspective, he brings anti-illusionism full circle. Matter is incorporeal, weightless and exists optically like a mirage. In his graphic diatribe, Metcalf foregoes a tradition of static relief for an animation that lies somewhere between sculptural movement and cartoon sequence.

Perspective becomes the goal of both Metcalf and Banyas in their systematic distortion of reality. The metalsmith's world, like all other artists' loci, begins with the maker's vision, a vision delineated within its communicative strategy that positions the viewer, the subject and the maker within an operative frame of reference. The maker "frames" his discrete world through the intuitive workings of method and materials. The maker asks us to accept the strictures of his perspective, for only then can we feel the resonance of his message. When we look at art, our lasting impression is not imagery or representation but the way the maker is looking at his subject that is germane to our experience.

Another example to illustrate this point is the work of Linda Threadgill. Threadgill uses the enclosed forms of the book and the shadow box to explore the visual inhibitions of narrative. She is questioning the stultifying effect of boundaries, as the physical matrix of the story is confined to static "prints," or frozen tableaus. Since the power of narrative, whether in folktales or painting, lies beneath the transitory story line, the "object lesson" of narrative sculpture must consequently summon the viewer's empathy. Only by overcoming the grip of a literal reading can our cognitive feelings for objects, relationships, situations, complete the psychological transference.

In Quarters, Threadgill's shadowbox is the volume of real space, unlike paintings space of illusionary effects. Here painting gives way to physical making. Although the orientation of the whole is still pictorial, that is, forward to the spectator, back to the wall, the illusion of deeper volume, of modeled surfaces, is forcefully presented. The room is cramped, tortured, claustrophobic. The objects are trying to escape. A wind seems to be sweeping through the rather placid still life. Bur it is not a liberating wind. All it can do is distort the inner sanctum, a grotesque surrealism. The wind rips at the wallpaper, tears the tablecloth, rocks the fruit bowl, tumbles the table. We feel helpless, inadequate, impotent. We are hemmed in by the encroaching walls. We are disarmed by the convulsive patterning of images as we desperately try to reconcile the turmoil that is its story. This well-crafted miniature engages us through its detail and manipulation and by its ambiguity of picture plane and sculptural volume. The problem of representation is not the issue. The internal ordering of the parts overwhelms the reference to reality. It becomes a self-sufficient object that insinuates itself in the emotional interplay of our experience.

The desire for a self-sufficient perspective manifests itself in another feature of contemporary metalsmithing, and, for that matter, all sculpture—the persistent problem of the base. The base is the sculptor's convention for "rooting" his art in surrounding reality while permitting it to stand apart. It creates an experiential zone both physically and psychically. It says in effect that this sculpted object has a life, a "presence," of its own. It creates an aura of distance and dignity around the object.

Throughout history, the base has been used to isolate a class of objects from all others—namely sculpture. But Modern art has realized the inherent dilemma. If the base distinguishes sculpture, then all objects are sculpture, since they all have bases of sons. Modern art has sought to dissolve the base both physically and psychically in order to unveil the true meaning of sculptural form, to explore the essential quality of "rooting' art in reality without the encumbrance of this convention. For metalsmithing, the base continues to confine the pre-Modern closure of its signature forms. Jewelry is defined by its attachment to the body, holloware to its natural foot, relief to the wall, while construction and "objects" still depend upon the architectual stability of the traditional pedestal or tabletop. This concern for the base is not mere captious criticism, nitpicking about a functional necessary, as metalsmithing has been transparent in its search for a recognizable feature that will identify it as sculpture in the modem tradition, and this feature might be the notion of the base.

Jill Slosburg's Terra Firma—Sky/Skin House is a mysterious vessel/hut perched upon a tall (56″) table/pedestal. The self-conscious working of the surfaces belies any simple explanation of this as a readymade base, as support for the object. This is a unified composition that stands on its "legs" in anthropomorphic confrontation. The inverted vessel, while similar in form, is not Metcalf's fool's cap, as the doorway beckons our inspection of the interior, a dark illusion of depthless space. It correlates the interior of a "familiar" vessel with the interior of the human body, the feelings of carnal inter-subjectivity. By raising the vessel to the height of the torso, Slosburg locates the Freudian area of heart and pelvis. As the vessel becomes more and more intriguing, the pedestal grows smaller and smaller in our awareness. Yet, without the pedestal, the vessel loses its referential identity. Where holloware's presence is often terminated by the functional appropriation of the user, Slosburg's vessel is disemboweled in affirmation of its integrity. We are caught in the "tension of the object." We want to right the upended bowl but are restrained by the fear that we will molest the figurative composition. We hesitate to enter the friendly confines of the womb/heart, unsure of its "unknown" psyche. The object keeps throwing back our normative responses. By distancing its personality within the experiential zone, it roots its reality in the viewers inhibitions.

Whether utilitarian or contemplative, metalsmithing relies on an almost quotidian appreciation of life's myriad details. The 20th century's quest for a monumental sculpture is a quest for meaning seemingly beyond man's grasp. Metalsmiths' sensibilities in this regard are understandably alien, as they are apt to document the existential occurrences of a functional metaphysic.

In Summer Dreams and Late Winter Buds, Gary Griffin relies on an organic analogy in the same way that Slosburg uses a corporeal one. In his work Griffin creates a "tree of life" that seems to grow into infinity. Yet he distorts its growth. He makes us pause at each interval, at each stage of its evolution to consider the details of memories, reflections of objects and situations that are as much a pan of our growth as a culture as the environment that is its model. C.E. Licka in his profile of Giffin (Metalsmith, Fall 85) characterizes his method: "He juxtaposes a series of representational images that pull the eye upwards like a film unwinding to its eventual denouement. . . The effect from a distance is like a silhouetted or antennalike structure resting in space. But it is in the details that the spectator becomes involved in processing the visual forms encountered." Griffin makes full use of narrative rooted in an evolving populist allegory. Yet he retains the inherent values of tactile objects to insure the viewer's mnemonic response. His constructions are personal landscapes of material culture found in situ among the remnants of decorative arts history.

Throughout the essays that accompany "Form Beyond Function." a consensus is reached that defines the metalsmithing genre circumscribed by size. Although Slosburg and Griffin have constructed full-scale (human scale) sculpture while retaining the condensed power of smaller objects, much of the work in the show appears resolute in accepting a smaller scale as the raison d'être for metalsmithing techniques. This has become a particular problem with respect to an evolving esthetic. Modern art's muscular dialogue of forbidding scale has left three-dimensional art timid in its wake. With the possible exception of Joel Shapiro, Wade Saunders and Charles Simmonds, there is little evidence of sculptors extolling the virtues of working with diminutive representation. Nevertheless, like planar perspective and physical context, psychological scale is an appropriate and fruitful arena for the modern artist's point of view and is denied by the histories of neither sculpture nor metalsmithing.

Artists committed to this perceptual strategy take the opportunity to explicate a "new" point of view that counters the customary reaction to small objects—which can be called a "regression towards the real object." Both John Ruskin and Roger Fry have established this phenomenon in the idea that knowledge will influence the way we see things. Messages are modified by what we know about the "real" shape of objects.

E.H. Gombrich provides an illustrative example on the subject, and it is worth quoting him at length. "We compare the penny in the hand with the house across the road. It is this imaginary standard distance which will influence the scale at which a child draws such objects and which will also determine our description of ants and men. The notorious question whether the moon looks as large as a dime or a dollar . . . may not allow a clear-cut answer, but most of us would protest if anyone suggested that it looks like a pinhead or an ocean streamer, easy though it would be to devise a situation where these statements would be true." This diversion into optics is not meant to offer a clinical methodology but rather to debunk any notion of inherent limitations in size and scale. It is to suggest, however, that esthetics challenge the artist to "devise a situation where these statements would be true." It proffers the opportunities of illusion in concocting a unique perspective where the artist's message is unfettered by and inseparable from its formal construct. Once again, it is not size that is at issue but perspective and its manifestation. Although the metalsmith runs up against a hardened perception with respect to "real" size, he can use this prejudice to his advantage.

Successful workings of smaller size are not without historical precedent. We need only cite the work of Cellini, Giacometti, Degas, Arp, Gonzalez and innumerable others to chart its heritage. No less critical praise has been bestowed upon these artifacts than on those of larger sculpture. For example, John Pope Hennessey, undaunted by Cellini's employment of small-scale and goldsmithing techniques, claims for him the title of the greatest Renaissance sculptor. "The appeal of these figures [referring to the Francis Saltcellar] is otherwise exercised through form alone, and in this respect they surpass, in communicativeness and articulacy, any small bronze produced in the middle of the sixteenth century. Capricious the Saltcellar may be, but in it Cellini successfully assembles poetic detail into a richly poetic whole . . . all contribute to an allegory of the consummate naturalness, and it is through this no less than splendor of its facture that a paragon of virtuosity becomes an evocative and memorable work of art."

This "paragon of virtuosity" accolade seems to reverberate throughout metalsmithing history as it pertains to "small forms." But beware of their ominous overtones. They ring of an inverse correspondence between size and intellect. As small hands create small objects, small minds are sure to be behind them. What saves them is their "virtuosity," the skill of rendering material into palpable form. Virtuosity hides in lapidary fashion the prosaic attraction for adroit technique.

In "Form Beyond Function," virtuosity often adumbrates esthetic intellect or the rendering of ideas into palpable form. There often appears conflict between expansive themes and the constraint of a prescribed scale of working. Rachelle Thiewes's Stella Bottero, however, is a sculpture comfortable in being a small object of "natural size." At first inspection, we see the material handling, the hewn organic slate contrasted by the turned polished supports. But scale intrudes almost immediately into our cognitive process. We know it is palm-sized and our memory bank acknowledges reality equivalents. When we look for objective correlatives to satisfy our inquisitiveness, we begin to feel the "spikiness" of the pointed legs, the "sharp" edges of the slate, the "razored" studs that emerge from its surface. The title of the composition suggests a feminine analogy, and we begin to sense that the legs are spiked heels, that a woman's character is bottled by a well-turned physique, polished and poised. Beneath this stereotypical image, or above it, in this case, there lurks an abrasive resistance, a studded rebelliousness, a dangerous consequence to categorization. It is a successful metaphor because its real size invokes the day-to-day associations of the object world. As a metaphor of manipulation, it craves to be manipulated, to be held and felt, knowing that its tactile qualities will reassure us that we have grasped its message. In our possessive intimacy we feel responsible for the object's consequences and challenged by the fabric of its relevance. We are left holding in our mind's eye an unresolved fragment of a larger composition that is our individual conscience.

In contrast, Kathy Buskiewicz's Extended Wholes questions the efficacy of the object and in doing so challenges a stolid feature of Modernist dogma. Michael Fried in his definitive essay "Art and Objecthood" proclaims for the object a lack of "interesting incident, an inert look that divests the art experience of the intercourse between maker and viewer. The object is the focus of attention but the situation, the experience of art belongs to the beholder-it is his situation." Besides the sterility of the form and the reductive shape, the use of scale is an operative prerequisite. Fried quotes Robert Morris that the awareness of scale is heightened by "'the strength of the constant, known shape, the gestalt,' against which the appearance of the piece from different points of view is consitantly being compared. . . . I wish to emphasize that things are in a space with oneself . . . rather than . . . one is in a space surrounded by things. It is intensified by the large scale of most literalist work. . . . The larger the object, the more we are forced to keep our distance from it. It is this necessary greater distance of the object in space from our bodies, in order that it be seen at all, that structures the non-personal or public mode."

But what is contentious in this concept, as illustrated by Buskiewicz, is the notion that only through enlargement of scale, of taking in more of the object that we can consume, is a dislocation of sensibility achieved, that the gestalt is only agitated by the threatening interference of magnitude. For Buskiewicz, atomic objects invert the spatial relations with corresponding effect. The gestalt is agitated through fear of omission. We seem to recognize these objects as part of our reality but don't understand their specific reference. Their shape and constancy of size are familiar but ambiguous. We need to fit them into the puzzle of our experience before the gestalt is completed. The monolith from which these objects emanate is not only an indication of self-referential scale but also a Suprematist wedge whose vanishing point leads into the personal space of the observer. Buskiewicz reclaims "scale" for the object in an inherent ability to encourage introspection rather than circumspection. The initial perception of her work as a vague whole and definite parts is convoluted because there should be a definite whole and no parts. Like the shape of the object, the materials do not represent, signify, or allude to anything. The "obdurate entity" is simply stated. The experience is one of endlessness, of inexhaustability, of being able to go on and on, letting the material itself confront us in all its literalness, its objectivity.

Allegory schizophrenia. personal space. the impoverishment of cultural authority, the reclamation of a disenfranchised identity are all symptoms of a post-modern art. Metalsmiths, sculptors, writers, painters, seeking the right forms, the right modes of expression, inevitably find solace in these mutual concerns.

Much of the metalwork being produced today is an outgrowth of historical evolution, based on form, material and technique and a consciousness of a particular cultural position vis-à-vis the other arts. Rarely has there been an overriding impetus to address social, political and philosophical issues in content and polemic.

One of the great surprises of "Form Beyond Function" in this regard is the galvanized emotion of the women metalsmiths. Their insistent voices drown out the rectitude of propriety and authority in the work of their male counterparts. They seem to thrust into the foreground a critique of patriarchy that lies at the heart of metalwork and its social implications. By decentering a cultural intractability, they are the most postmodern of all.

That more than half of the work in "Form Beyond Function" is made by women artists assumes a "feminine" perspective, which has yet to be explicated by an appropriate gender criticism. Though this particular "mode of perception" remains elusive. the ideological position-taking is clearly present. One cannot speak of jewelry, holloware and other decorative "domesticities" without considering the "fetish" of adornments, the equivalence of beauty in feminine forms, the vessel as containment and sexual dominance, the object as icon of household ritual. All have lent material credence to a "feminist" response in metalsmithing.

In the work of Linda Threadgill, the inwardness, foregrounding of material, the illumination of process in coming to grips with an imposed environment is made more profound in dialogue with Holly Cohn's venues of desultory shadows and estranged relationships. Rachelle Thiewes's defiant "brass knuckles" is as foreboding as Jill Slosburgs sexual innuendo. Enid Kaplan's hapless marionette, held akimbo by invisible forces, is as critically autobiographical as Kate Wagle's twisted, confused, schizophrenic bridal bouquet.

If any themes predominate, they are those of restrained violence and unresolved confinement. Martha Banyas unmasks stereotypes. Martha Glowacki in Black Bush Arbor creates more a crown of thorns than a sweet-smelling laurel wreath. Munya Avagail Upin surrounds her vessel of sexuality with barbed wire, while Christina Depaul guards her bottomless temple with a spearlike fortification.

The vessel, the object, the box; the malleable material, the fascination with patina; the close tight, private working methods are as much a part of the vocabulary of metalsmithing as they are of the feminine condition. It is a testament to these women that their imposed language should not continue unquestioned, that the evolution and acceptance of form should be supplanted by cultural iconography and social function as the priority of content. It is not with a unified voice that these women speak but a distinctive one. In many cases, it is not an articulate voice but one that resounds with honesty and commitment. Its expressive timbre heralds a future of engaged content that has the potential to invigorate the entire field.

However, the agenda has yet to be set for adequate discourse. The incipient signs of their rhetoric has yet to evolve a suitable construct. The conceptual thickets of Susan Kingsley's nests and the "Pandora's Box" of Carol Kumata's environments are as much of a comfortable extension of metalsmithing history as they are a diatribe against suppression. If there is one symbol that commends the feminist mandate, it is Harriet Berman's Everyready Working Woman, those prosaic objects, those precious shackles of anomie, are appliances of sexual and economic repression, salvos of a malleable consciousness. Harriet Berman and her colleagues do more for this exhibition than the curators envisioned. Their work addresses more than sculpture beyond craft or form beyond function, it questions the viability of metalsmithing's function beyond form.

"Form Beyond Function" was cosponsored by the Mitchell Museum, Mr. Vernon, IL, and the Society of North American Goldsmiths. The exhibit traveled to the Cococino Center of the Arts, Flagstaff, AZ; The University of Texas, El Paso; the National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN; and the Wichita Art Association, Wichita, KS. A catalog with an illustration of each artist's work and essays by Prince, Kington, Griffin and Metcalf is available from Richard Mawdsley, School of Art, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901 for $5 (make check payable to SNAG).

Notes

- The notion of "sculptural illusion" first surfaced in an essay by Clement Greenberg, "The New Sculpture," Art and Culture, Boston: Beacon Press, 1961, p. 144.

- H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960, pp. 302-303.

- John Pope-Hennessey, Cellini, New York: Abbeville, 1985, p. 115.

- Michael Fried, "Art and Objecthood," Artforum, v/10, June, 1967.

Michael Dunas writes on craft, art and design.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.