Gary Justis

10 Minute Read

Imagine a small boy in a Kansas field in the 1950s. The boy, aged five, has constructed a wooden airplane with two seats, one for himself and one for a friend. He has tilted the plane toward the sky. Attached to the front of the plane toward the sky. Attached to the front of the plane is a propeller with a large rubber inner tube wound tightly to launch the plane up into the heavens. He is utterly, completely certain that once he has wound up that rubber bard the plane will propel him into a new and transcendent realm for investigation, out of reach of the tediously restrictive aspects of childhood.

Despite the failure of his first attempt, that Kansas boy, now the Chicago metal sculptor Gary Justis, continues, forty years later, to construct complicated, mechanical and enigmatic objects as vehicles of transcendence. While Justis is known nationally and internationally, he is somewhat out of the mainstream of contemporary postmodern art, a period known for its challenges to the use of objects for artmaking and the emphasis of the idea behind an art work at the expense of materiality and craftsmanship. Even at age five, Justis had become convinced that an object "could, in a sense, be the mind's salvation." During my recent visit to his studio on Chicago's North Side, the artist stated "that we could use objects to escape and put our minds in a different plane, much the way great literature does. It think objects can do that. Paintings certainly can."

Justis, who has been labeled a "maverick" by Chicago Tribune critic Alan Artner, continues to champion what might be termed craft values. As a result of a personal art philosophy that is both highly intellectual as well as humanistic he makes both non-functional metal sculpture and functional metal objects. These values enable the artist to find metaphor, even magic, in objects of daily use, a kind of mythology within the mundane; and they emphasize the use of the human hand and keen craftsmanship.

Considering the works and the assumptions which help to produce them, it is probably no surprise to learn that Justis studied ceramics at Wichita State University, where he received a BFA. He moved on to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, receiving an MFA in sculpture in 1979, where he then taught for many years. Currently he teaches sculpture at Northwestern University.

Justis grew up in Maize, Kansas, the son of a contractor and part-time inventor, who ran a backyard shop at home to devise new kinds of sod planters and reciprocating saws, as well as go-carts and other peculiar vehicles for the children in the family to drive around their Kansas property. "I've always seen my work as a kind of extension of my father's dialogue with functionality," the artist said. "He was trying to invent tools to make his life easier."

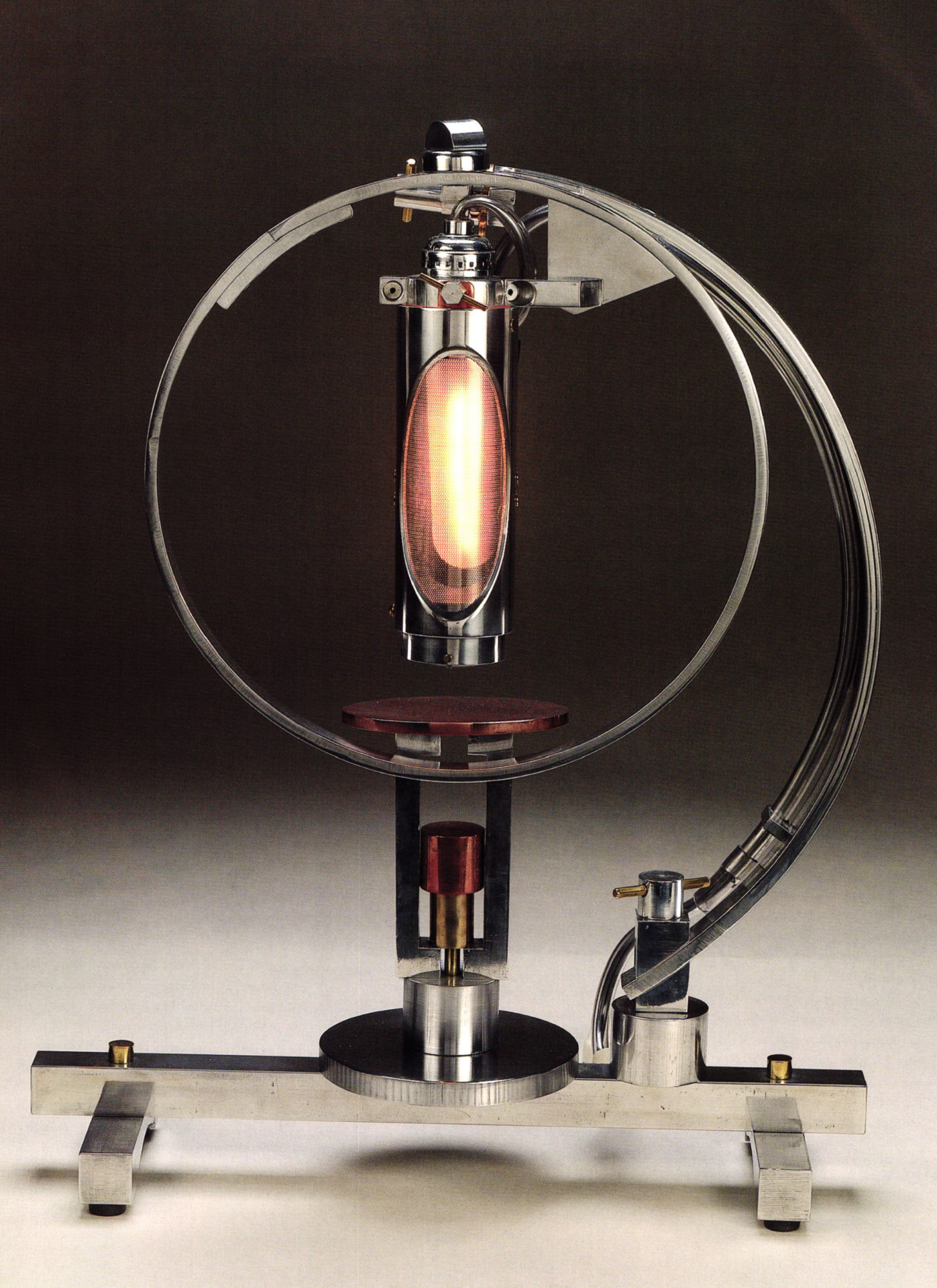

Function has been a major theme in the sculptor's work for the last twenty years. Indeed, most of his work is always doing something. Small motors run, lights blink, gongs chime, arms rotate or spin, each movement carefully timed to repeat, over and over, at a specified interval of time. These cycles of movement and sound, which can range from twenty seconds to three and a half minutes, are meant to induce a startled, then a meditative instant for the viewer, startled in the surprising discovery that the works emit sound and move, and meditative in the wait for these eruptions to repeat again and again. "I'm hoping to draw attention to that strange realm of anticipation where time begins to slow down and then stops," Justis said. "It's a way of using time and movement as a kind of malleable material. Movement becomes a material you can manipulate, and time becomes a material that is plastic. It can be stretched, or limited, or pressed. It's a subtle sort of material, it's visually elusive, but it's a material none the less." Justis's Untitled, 1992, which was included in the prestigious Art in Chicago 1945 - 1995 survey exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago this year, is a good example. The 9 foot-long, highly polished aluminum structure contains a small gong that pings musically when a hammer strikes it gently at regular intervals.

Paradoxical combinations abound in Justis's work. Many of the objects, from the purely aesthetic sculptures to the chandeliers which actually light a space, are gorgeously crafted, handmade machinery, all drilled, polished, cut and assembled by Justis in his studio. These are machines, but they are also aesthetic objects, meant to be icons or meditative tools. For a time, Justis constructed machine art that referred to ancient gods and was based on his longstanding study of Marcel Duchamp, whose machinelike constructions shrewdly blended art and life, the sacred and the useful. Duchamp's 1923 masterwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, also called the Large Glass, now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is an ambiguous assemblage of machine images pressed between large glass plates. The Large Glass stands as an extraordinary mixture of machinery, mythology, and eroticism. Duchamp's drive to strip art of its pretentiousness - insisting that art can be made out of anything, from everyday materials to the most complex processes, such as physics - goes to the heart of a Justis sculpture, with its roots in equipment, technology, and tools. The kinetics in Justis's art also recall Duchamp, whose interest in the representation of movement occasioned the notorious painting Nude Descending a Staircase in 1912.

At its most basic level, Justis's art is an attempt to reconcile the age old conflict between technology and nature. Much of his latest work is horizontal, which often brings to mind a landscape. The idea of healing the breach between an industrial landscape and a natural landscape goes back to Justis's experience of wide open farm fields in Kansas; but it also indicates his ease with mechanics and his ability to link the garden of the imagination with technical prowess. These are qualities not always found in the art world now. While the artist likes to point out that we are in a post-industrial age that is "beginning to look on machinery with a sort of nostalgia," many viewers are still brought up short by an art that plays out the enigmas and myths of our organic, human consciousness through hard-edged mechanical objects and techniques.

And technique, especially the craftsmanship of the hand, is a deep and abiding love for Justis. "I think that the hand is inextricably linked to the processes of the mind, so that's why I think it's important for me to build my own pieces," he said.

"I want a dialogue with the work. For me, an act of making art is a continual dialogue, very physical, very athletic, and at the same time intellectual. That goes counter to current art thinking. With a lot of the new art, the metaphor comes from the purity of the idea. The object has become secondary, so it has to have not little catching points on it that the eye will stop at and question, because that brings you into the world of materiality. Things that are manufactured are devoid of those little character attributes that come from hand work, and are perfect for that kind of thinking. For me, the material forms a dialogue and it does have expression within the minutiae and within all the tiny little things that we see on the work. And those figure into the overall idea. So to me any technique is a vehicle for expression."

Oddly, this idea also comes from Duchamp, who thumbed his nose at the art world earlier in the century by introducing his Readymades, a series of store-bought bottle racks, urinals, and other paraphernalia which he signed and submitted to exhibitions as art objects in an attempt to expand the definition of what art really was. Duchamp, however, actually was a craftsman, who spent eight years painstakingly constructing the Large Glass. "Duchamp said it's very important to have good craftsmanship, so the shoddiness of bad craftsmanship doesn't get in the way of the purity of the idea," Justis said.

Justis works primarily with aluminum, which he buys in large bars and sheets and then cuts, polishes, and assembles, although he has also used brass, copper, wood, small motors, and electronic parts as well. Aluminum's workability, neutrality, and reflective capabilities are all attractive to Justis. Aluminum has a kind of old but new age reputation as well, giving it identities in the past, the present, and the future. The sculptor never welds his works. Every component is assembled with joinery, partly to escape toxic fumes from the welding process; but primarily Justis uses joinery from a practical, functional point of view. This method of fabrication allows the artist to adjust each part of the work. It expands the vocabulary of each component, and it allows him to break down and reassemble the piece for shipment to museums and collectors. "I'm always fascinated with things that are totally adjustable and mutable and can be changed in scale and function and appearance and so on because of that adjustability," he said.

His preoccupation with function as a concept has been a constant thread throughout his work and has led him down many paths. Early on, he investigated the linguistic history of the word function and discovered that one definition of the word paradox is "beyond function." "I thought that sculpture has a very paradoxical nature to it," he said. "On the one hand, it is very useful; it has an aesthetic function and, on the other hand, it is totally useless. One the one hand, it is very valuable, and on the other hand it is valueless. So there's a paradox that's a given within the realm of art and I wanted to understand that at a deeper level."

During the 1980s, Justis made a series of hyperfunctional sculptures, works whose origins might have been functional, but which, through kinetics, sound, light, and movement, had a new, absurd, tongue-in-cheek appearance. Stretching and distorting the meaning of function he created chandeliers with pulsating lights or moving parts so that their usefulness was practically voided. Such pieces allowed him to investigate the boundaries between function and non-function and to question why the two categories were separate in Western European culture. The sculptor has slightly toned down his utilitarian work now, although he is currently working on a memorial that includes a chandelier with text attached to it. But his most interesting works continue to be sculptures that ride the edge, attempting to marry of reconcile function and non-function, as in Stone's Mill, an aluminum and bronze lamp with rotating scissorslike arms. Lit from above the piece creates ever-changing shadows on the wall. Easel, 1995 is a seven feet high aluminum, copper, and wood structure that dwarfs any picture placed on it.

"You know, the more you get into any discipline, the more you discover how much you don't know," Justis said wryly. "And so, I find myself in these philosophical dilemmas time after time. And I haven't really come to any definitive conclusions about function and non-function. In retrospect, I think that's very good because it's kept me moving forward. Because if I discovered anything definitive, if I came to any solid place in my philosophy, I would stop making art. There wouldn't be any reason to push forward, because all the information is there. I've solved the mystery, so why go on?

Polly Ullrich is an artist and writer living in Chicago.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.