Goldmines, Goldrushes and Nugget Jewels

26 Minute Read

"…GOLD - EVERYWHERE THE GLINT OF GOLD." THESE WERE THE WORDS RECORDED BY HOWARD CARTER TO DESCRIBE HIS INITIAL GLIMPSE OF THE TREASURE OF THE YOUNG EQYPTIAN KING, TUTANKHAMEN, WHOSE TOMB HE DISCOVERED ALONG WITH LORD CARNAVON IN 1992. THIS EXTRAORDINARY FIND, OF UNPRECEDENTED SCIENTIFIC AND HISTORIC IMPORTANCE, WAS REDUCED BY THE FAMED ARCHAEOLOGIST TO "GOLD," THE MOST DAZZLING, DURABLE, AND MEANINGFUL OF NATURE'S ELEMENTS.

Carter's response to the three thousand year old entombed treasure, however, demonstrates the timeless allure of this metal. Its significance, originally linked to gold's inherent properties of sun-like brilliance, resistance to corrosion, and malleability, was enhanced no doubt by its rarity. For the ancient Egyptians, it also had profound implications into the afterlife. Upon completion of the embalming process the deceased was ideally encased in gold. Masks, caps for vulnerable fingers and toes, and occasionally entire coffins were crafted from gold sheet. Considered "the flesh of the gods," this immutable metal was viewed as a means of attaining immortality.

The ability to export gold was one reason for Egypt's ascendancy in the ancient world, enabling its rulers to obtain raw materials such as copper, tin, and silver from the East. It was also a source of wealth for Nubia, Egypt's rival and neighbor to the south (Fig. 1). Known also as Kush, this gold-rich region, whose boundaries extended southward from Aswan to Khartoum, was known in antiquity for its alluvial deposits and numerous auriferous tracts which stretched eastward across the desert to the Red Sea. Nubian burials were also accompanied by finely crafted objects of gold and both archaeological and written records document the mining and exportation of this most precious material.

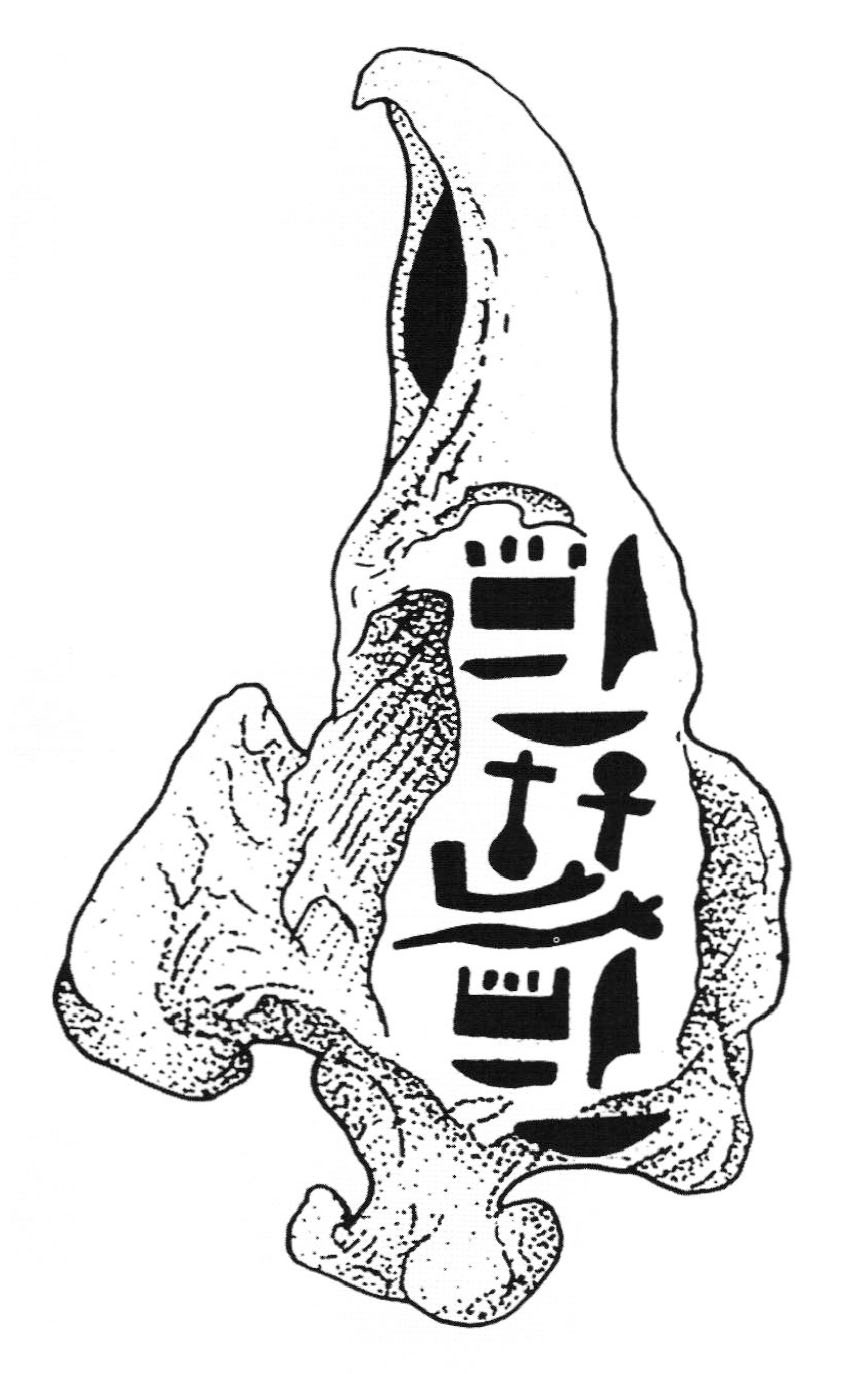

It was in Nubia, in fact, that gold nuggets were first adapted and used as ornaments. The earliest known jewel of this type belonged to an ancestor of Piye, the first Kushite king (Fig. 2). This mid-ninth century B.C.E. ancestor or chieftain was buried in a pit grave under a circular gravel mound at el Kurru, an early Kushite cemetery not far from the Nile's Fourth Cataract. Although the grave was partially plundered in antiquity, several items of jewelry were found in situ around the head, chest, and left hand. They include a gold lunate earring, a plain gold finger ring, and two necklaces. The nugget, pierced for suspension and inscribed with a dedication to the god Amun, belongs to one of the latter. It measures 30 mm. h. x 17 mm. w. A suspension boring was artfully situated by the ancient craftsman in an elongated outgrowth that simulates a bail. The surface was planned to provide a flat surface for the inscription which reads, "The Lord (god) Amun, may he give the perfect life." This dedication establishes a relationship between an earthly material (gold) and the divine or magical. Its inclusion in a royal burial also marks the nugget as a prestige or status item. In fact, two of the thirteen nugget pendants from Napatan tombs at nearby Nuri and Meroe come from royal burials. These later nuggets, smaller and uninscribed, were found amongst the plundered remains of two queens buried nearly a century apart. In the case of Queen Madiken, buried at Nuri around 500 B.C.E., the 12 mm. long nugget was found on a gold wire necklet. Other items on this wire include two granulated ring beads and a rough triangular pendant of amazonite also known as microcline or green feldspar.

Another nugget (Fig. 3), the largest so far recovered from ancient Nubia, comes from an intact male burial in the western cemetery at Meroe. It was found around the neck of the deceased, the leather or flax stringing material long disintegrated. Soldered to this 50 gram specimen is a hand-fabricated gold bail whose internal edges show signs of wear, a clear indication that this bold and substantial jewel was worn in life as well as death. Electron microprobe analysis by Richard Newman (Department of Objects Conversation and Scientific Research, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) determined that the nugget was about 91.2% gold, 8.8% silver and 0.08% copper. Very similar findings were obtained for the bail while the solder was found to contain about 78% gold, 12% silver, and 10% copper.

Adjacent to the nugget pendant from Meroe West 859 was an unworked lump of amazonite which as bored for suspension. This material, durable and no doubt highly valued for its color, also had divine and royal connections. An earlier specimen inscribed for King Taharka (690-664 B.C.) in the Brooklyn Museum uses to advantage the edge of the crystal for the funerary text (Fig. 4). As with the first nugget jewel, this caged royal pendant reinforces the connection between an indigenous natural form with position, power, and religion.

For the ancestors and rulers of the Kushite Dynasty in Nubia, gold not only captured the very essence of the gods and endowed its owners with magical capabilities, it permeated the landscape and was a source of national wealth. To a certain extent this indestructible metal defined both the land and the people. And the jewel, which so dramatically expressed this relationship, was the placer nugget pendant.

Of course, Nubia was not the only land in the ancient Near East rich in alluvial gold deposits. The fifth century B.C.E. Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote an extraordinary source in the Pactolus Valley (modern Turkey). A nugget (Fig. 5), now in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara and dated to second half of the sixth century B.C.E., is believed to originate from this ancient mining site. It is pierced and fitted with a gold wire suspension hoop. The Lydians, credited with developing the gold refining process as well as the first system of coinage, no doubt saw in the nugget a symbol of their newly defined status in the world.

The classical world obtained its gold from a variety of sources which included Thrace, Macedonia, and the Balkan Peninsula for the Greeks and the Pennine Alps, Noricum, Britain, and Spain for the Romans. It is not surprising that there are no known nugget jewels from this period as neither civilization sought definition or identity through gold. The Romans, in fact, were known for their penchant for exploiting the world's resources.

While known goldfields were reworked over the next millennium, there was an increased tendency toward recycling. By the Middle Ages, it was standard practice for the customer to supply the goldsmith with gold and stones garnered from older items. Supply could not keep pace with demand, however, and the tale of El Dorado circulated, giving rise to a whole breed of explorers who, filled with dreams and ambitions, sought to discover a land of infinite wealth.

El dorado is Spanish for "the gilded one" and one version of the legend purports that it was the name given to an Inca chief of Mañoa, a city on Lake Parima in Venezuela. This mighty and fearless ruler would reportedly plaster his body with gold dust on an annual basis followed by a ritual bath in the lake to wash off the gold. In 1534, Don Pedro de Heredia searched Colombia for the fabled kingdom. Although he failed to locate El Dorado, he, like conquistadors before and after, did indeed find an abundance of gold.

Initially it was freely given or traded with the newcomers. Gold would subsequently be seized from the natives and their temples and graves looted. Later, as the sources were discovered, placer and vein mining would be established employing natives and Africans to work as slaves in the mines.

It is telling of the connection between the church and state that the first gold to reach Spain from Hispaniola (modern Haiti) in 1495 was given by King Ferdinand V to Pope Alexander VI in Rome and was hence used to gild a cathedral dome. It has been estimated that from 1500-1650, approximately 180 to 200 tons of gold were seized from the American "kingdoms of gold." It is a sad commentary that Europeans returned to the furnace the hand-wrought treasures they so greedily plundered. Archaeological remains from the Americas, however, attest to the sophistication and skill of native metalworkers whose efforts were so recklessly discarded. Like the Egyptians, "the Andeans associated gold with the life-giving sun, the deity that brought warmth and fertility to the soil and to humans." Pre-Columbian cultures do not appear to have appreciated the noble metal in its native state. Rather, finely worked objects for bodily adornment were highly valued. The Spanish, however, specially prized large nuggets. It is recorded that a nugget weighing 600 ounces was lost in a shipwreck on its way to Spain from Hispaniola in 1502. A nugget more than twice as large, weighing 1,503 ounces, was recovered in Peru and "forwarded to Spain for presentation to Charles V (1517-1558)."

Spurred on by the magnificent finds in the Caribbean and later, Central and South America, the Spanish conquistadors extended their search northward. In the first quarter of the sixteenth century, Spain had tangible proof of gold in North America. Sea captain Alonzo Piñeda reported in 1519 that the inhabitants of North America wore gold jewelry and that gold nuggets were to be found in the rivers. In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez, Spanish governor of Florida, questioned Indians living near Tampa Bay as to the source of their gold. They claimed that it was from a region in the north called Apalachen (sic). Hernando de Soto received further proof of the existence of gold during an expedition to the southern Appalachian mountains in 1540, when a young native described the methods by which the locals "mined, melted, and refined" gold. The explorers were impressed by his knowledge commenting that the young man had either seen the process or "…else the Devil had taught him how…" Although the full extent of the discoveries made by the conquistadors in North America in unknown, there is limited evidence which suggests that the Spanish actually mined in the Southern Appalachians.

In 1799, Conrad Reed, son of a farmer in western North Carolina, made a chance discovery that gave birth to a new generation of prospectors and led to the identification of a southern gold belt. Reed returned home from a fishing trip on Meadow Creek with a seventeen pound glittering stone that was relegated to the role of doorstop. It must have come as a surprise when three years later the stone was properly identified as gold ore! Farmers in the area began searching their property for gold as word of the find spread. The southern gold rush began in earnest when Mathias Barringer, a farmer and part-time prospector, made a discovery in 1825 while digging along Long Creek. His serendipitous find later led to the identification of an important gold-bearing quartz vein which ran from Virginia through Georgia.

By the early 1840s, the easy placer mining was exhausted in the south and such work was no longer profitable. However a new El Dorado was soon to be discovered out west. James Marshall, the partner of John A. Sutter in a sawmill scheme, found pieces of gold in a fork of the American River in January of 1848. Marshall, once he had ascertained that it was gold, immediately reported the find to Sutter and they plotted to keep the discovery a secret to protect their business. Nonetheless, as more gold was discovered, words of the finds spread.

In his annual address given to Congress, President James K. Polk proudly announced that hidden treasure lay buried in the booty of the Mexican war. Polk's address gave a sense of validity to the claims which had been previously dismissed by the President, who noted that the wealth of California was known at the time of acquisition, thousands rushed west. His speech launched a stampede and had a dramatic impact on the territory. Towns sprang up overnight and San Francisco was transformed from a sleepy bay to a west coast metropolis. Spurred on by the news of gold in "abundance", many southern prospectors as well as pioneers from the North East, Europe, Mexico, and China undertook the long and perilous journey to California. Pamphlets dating to 1849 and 1850 were circulated in French, German, Dutch, Swedish, Russian, and Polish, each discussing the route to California and the methods of gold mining. All males who had reached California by December 31, 1849 were eligible to join as founding members of the Society of California Pioneers. Although some of the early pioneers did find their fortune, for most it was arduous and unprofitable work. Inflation was high and many who became wealthy during the gold rushes were entrepreneurs who provided goods or services to the miners and their families.

Many silversmiths and jewelers were attracted to California and moved West along with would-be prospectors. California was, despite her wealth of raw materials, a frontier land lacking both the facilities and expert craftsmen needed to execute ambitious and sophisticated commissions. A medallion in the collections of the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum illustrates the capabilities of local metalsmiths in the early days of the gold rush. This commemorative item, one of several pendants made in celebration of California statehood (1850), was presented to members of the San Francisco Board of Aldermen. Hand-fabricated from two gold plates joined by rivets, the front is appropriately decorated with thirty-one stars while the word "Eureka" encircles a large central nugget set within a star. A circle of smaller nuggets borders the outer edge. The inscription on the reverse indicates that this particular medal was made for Colonel William Greene, President of the Board of Aldermen from 1850-51. Apparently there was a bit of controversy surrounding the medals as they were originally purchased at the cost of $150 each with funds from the public treasury. When the medals became "…object(s) of ridicule," the Aldermen were given the option to purchase them with their own money or return the, so that the proceeds obtained from the melting pot could be returned to the treasury.

While there is evidence to support the claim that early metalsmiths engaged in limited craft production, it is apparent that they were basically occupied with repairs or works of simple design. It was not long, however, before jewelers and businessmen with aspirations of catering to the needs and whims of the newly rich were attracted to the west coast cities. The firm of Shreve and Company, established in 1852, was among the first in San Francisco which hoped to capitalize on the boon created from an expanding mining industry. However, they did not establish a workshop for the production of jewelry and silver until 1881. While the bulk of the company's early records was lost in the fires of 1885 and 1906, a catalogue from 1904 illustrates several examples of quartz jewelry, including popular mining designs such as the single shovel and the crossed pick and shovel with pan, recognized as the international emblem of miners and mining.

Simple pieces of nugget jewelry were also made for miners, mine owners, and their families. Obviously the use of the nugget in its raw state would identify the wearer as having direct connections with the romantic business of mining. One interpretation of nugget jewelry is that it extends from the long tradition of wearing a trade emblem, such as a hat badge or a guild or signet ring, that visually signifies one's affiliation. Nuggets would certainly be recognized by all as the product of adventuresome miners. A common scenario would involve the miner bringing a small bag of specimens to the local jeweler. Occasionally they would agree upon exchanging the gold for a ready-made article. They could even discuss the creation of a custom piece of jewelry using the nuggets supplied by the miner.

Technically, nuggets can be easily joined and made into chains, bracelets and pendants by adding small soldered loops. Often the final product would take the form of a watch fob or stickpin, both utilitarian items. In fact, many watch fobs have since been converted into more marketable items such as necklaces. Sometimes, however, the miner would request that nuggets be fashioned into a piece of jewelry that would then be given to a family member or loved one. The Oakland County Museum holds in its collection a threestrand necklace which contains fifty gold nuggets. Fortunately the provenance for this piece is known - a share owner of the Argonaut Mining Company presented it to his daughter around 1900 - a valuable token of his pride and affection.

The gold rush which began in California was only the first among many that would begin in the second half of the 19th century in the U.S. and abroad. Ordinary folk who dreamed of striking it rich would have other opportunities to try their luck as gold was soon to be found in all of the western states. Jewelers followed the trail of prospectors, confidant that their skills would be put to use. A piece of mining jewelry, most likely from one of the western states, is a pin which also functions as a watch enhancer (Fig. 6). Elaborate and pictorial, this early 20th century pin appears to have been inspired from either a real-life landscape or a photograph. Depicted is a log cabin nestled within a mountainous landscape. The setting sun marks the end of a miner's arduous day while his tools, a pan and shovel, have been deposited outside. The panorama is heightened by the careful placement of colored gold leaf on the surface - the trees are tinted pale green and the sun is a subtle pink hue. The mark stamped on reverse, "Billo, 14K," has not yet been identified. However, the imagery bears an uncanny resemblance to the mining region of Colorado.

As with California, it was a river that first yielded bits of gold that sparked a bonanza in Australia. In 1823, surveyor James McBrian reported finding gold particles in the Fish River near Bathurst, New South Wales. For various reasons, the discovery was kept secret, the primary one being for the sake of law and order as Australia had been established as a penal colony. Additionally, McBrian presumed that with finds so small, mining ventures would prove unprofitable. It would be another thirty years before he was proven wrong. Later discoveries in the 1830s and 1840s were also suppressed by officials who feared the reactions of prisoners should the news become public. However, when the discovery of gold in California created an exodus for the Golden State, officials announced a discovery by Edward H. Hargraves. Hargraves, who had recently returned from an unsuccessful prospecting venture in the gold fields of California, recognized a similarity in landscape of New South Wales. When he panned gold from Summer Hill Creek in February of 1851 (coincidentally near Bathrust NSW which McBrian had deemed uneconomical), he bragged that he would open the "age of gold." Once his discovery was confirmed, he received a £500 reward and was appointed the Commissioner of Crown Lands. That authorities soon released the welcome news of his discovery to the public and prospectors flooded into the area. It was only a matter of time before discoveries were made throughout the provinces of Australia. By 1855, mining jewelry in the form of brooches, pins, and chains were available for newly rich and enthusiastic travelers.

While among the last of the gold rushes of the nineteenth century, the discovery of gold in the Transvaal region of South Africa began a new chapter in the epic tale of world gold. The story begins in October of 1853 when Pieter Marais found gold in the Crocodile River. As a veteran of both the California and Australia gold rushes, he was well versed in the foibles of gold mining. Confident that the earth would yield more of her golden treasure with greater investment, he journeyed to Potchefstroom, the Boer capital of the Transvaal, to seek support. On the basis of his report, an agreement was signed in December 1853 with the Boer authorities giving themselves the authority to carry out a death sentence should Marais "uncover a gold mine" and share this information with foreigners. In 1854, he continued to prospect and did find more gold but apparently not in sufficient quantity to persuade his Boer patron to continue to subsidize his speculation.

Small finds of gold were reported in subsequent years and there was a minor rush on the Blyde River in 1874. However, the big find would come in 1886 when George Walker discovered an auriferous rock on Langlaagte, the Oosthuizen family farm. Langlaagte was in the Witwatersrand (Ridge of White Waters) region of the Transvaal. This area, known as the Rand, lay atop a landlocked reef of rich ore-bearing rock. The Dutch settlers of South Africa, known as Boers, had lived in the Transvaal since 1835. After gaining control from the British in 1881, the Boers were none too pleased to have a largely British immigrant population occupying their territory while digging for riches. Paul Kruger, President of the Dutch South African Republic, planned carefully to maintain control of Boer land. He determined that a mining city should be established in an orderly fashion and subsequently the city of Johannesburg was founded in 1886. In the nearby digging fields, however, miners soon realized that the gold formation was quite different from that of California and Australia. The gold itself was concentrated in an enormous reef about 300 miles long. Their endeavors were known as the "millionaire's gold rush" due to the large amount of money needed to extract the precious metal. Several large companies were formed by those who had already earned fortunes from the prolific diamond mines. Much of the investment for the gold mining came from the British and tensions increased between the Boer community and British nationals who now had a great economic interest in South Africa. The struggle for profits and power led to the Boer War.

One jewel from the mining fields is a brooch of the standard mining design (Fig. 7). The nugget-adorned crossed pick and shovel are featured with a central pan from with a small pail pendant. The surface of the shovel is decorated with a nugget as well as the words, "SOUTH AFRICA/Johannesburg." In addition, four nuggets are placed in the corners of the pan and a small diamond is centered in the basin - a testament to the joint bounty of the region. The pin dates to the late 19th century and is marked "18K" on the reverse.

The last great gold rush of the 19th century was in the Klondike region of Alaska and Canada. From the mid-19th century, pioneers had traveled north in search of gold and minor discoveries encouraged further searches. The real find eluded all until a chance discovery in 1896. Skookum Jim, an Indian prospecting with a group of men, stopped for a drink of water before returning to camp with a moose he had killed. Fortune smiled upon him for he found a number of nuggets in what was then called Rabbit River, later renamed Bonanza River. Jim reported his find to George W. Carmac, a white man in his party. Discrepancy arises as to who should be credited with the discovery for Carmac claimed that he had found the gold, although he also did stake claims for the two Indians in his group. Once word spread that gold had been found in an appreciable size and quantity, another gold rush was born. Those already living in the area hurried to stake a claim and thousands began to pour into the northern territory.

Scagway, Alaska, situated on the Taya Inlet and strategically positioned at the confluence of the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails, came to be known as the gateway to the gold fields. It was a port of entry for many who came to try their luck in the Yukon and this area thrived as a gold rush town at the turn of the century. A fraternal order known as the Arctic Brotherhood was established in Scagway in 1899. They took as their symbol the minder's emblem of the crossed pick and shovel with a central mining pan and added the initials "AB", Lapel pins were made to be worn by members, an example of which is preserved in the collection of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Small in size with a diameter of 1.5 cm, the gold pin is crafted in two parts. The top piece takes the shape of a gold pan which is marked "AB" and decorated with three small nuggets. The records of the Klondike National Park Service indicate that the nuggets were panned by the original owner of the pin, Ralph "RR" Mason. By 1900 the Arctic Brotherhood had built their first meeting building in Scagway which stands today and is a popular tourist attraction. The Victorian rustic façade with a mosaic pattern of driftwood and stick proudly incorporates their identifying emblem and reminds all visitors of the exciting history of the town.

Our knowledge of the meaning of nugget jewelry in the ancient world comes directly from ancient sources. For those intimately involved in gold production, there is an appreciation for the natural form that defies aesthetics. Meaning in this context derives from an identity with the land and natural forms. This applies to the 19th century miner outfitted with simple nugget chains or watches with nugget-encrusted surfaces. Vicarious meaning, however, could be obtained by those indirectly involved in the discovery and extraction of gold yet spurred by its association with fame, glamour, and wealth.

It is not a coincidence that a different type of jewel, the souvenir nugget item, achieves popularity at the height of the Industrial Revolution. It is, in effect, a by-product of a growing consumerism. Travel during this period, once the prerogative of the upper classes, was embarked upon with great enthusiasm by an increasing number of people. For those adventurous souls who rejected and spurned the Grand Tour and opted for the frontier lands of the American West, the Australian Outback, the Yukon, or South Africa, the appeal of jeweled souvenir items as a badge of their courage is obvious. The imagery in both instances was specific to the site, i.e. mosaics of Roman ruins for the Grand Tour, the tools of the gold worker for the adventurous tourist. In case the iconography left any doubt as to the source of the jewel, place names were sometimes included, such as the popular "ROMA" jewels and mining brooches with the town name on a banner.

The romantic image of the gold miner remains a part of our imagination. Nineteenth century mining jewelry is avidly collected and continues to be a source of inspiration for contemporary craftsmen. Such as the nugget encrusted sterling silver belt buckle designed by the Canadian sculptor Thomas R. McPhee (Fig. 8). The idea for the composition derives from a black and white photograph of the Klondike region by E.A. Hegg (1898) entitled, The Exhausted Stampeder. Surface decoration using small nuggets and cast nugget look-alike continue to be made and purchased in those areas once known for their mines.

Yvonne J. Markowitz is the Suzanne E. Chapman Artist, Department of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art, and a Ph.D. Candidate in Egyptology, Brandeis University.

Janis L. Staggs is a graduate student in the Cooper-Hewitt Decorative Arts Program.

NOTES

This necklace, now at the Sudan National Museum in Khartoum, consists of sixteen biconical beads of gold sheet, the pierced nugget and a hollow gold Ptahtek amulet.

The ancient site of Meroe lies on the western bank of the Nile, midway between the 5 th and 6 th It became the center of Nubian civilization between the 3 rd century B.C.E. - 3 rd century AD.

The nugget was excavated by George Reisner of the Harvard-Museum Expedition in 1923 from Meroe West 859 and dates to the mid- seventh to mid- sixth century B.C.E. It is now part of the Nubian Collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (23.311.).

In the Nile Valley, green stones were symbolic of growth, regeneration and rebirth. See R. Wilkenson, Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art, London, Thames and Hudson, 1994, p. 108-9.

Ronald W. Lightbown, Mediaeval European Jewellery, London: Published by the Victoria and Albert Museum with the assistance of the Getty Grant Program, 1992, p. 34-5.

Malcolm Maclaren, D.Sc., Gold: Its Geological Occurrence and Geographical Distribution. London: The Mining Journal, 1908, p. 633.

, p. 615-616.

Brian M. Fagan, Kingdoms of Gold, Kingdoms of Jade, London: Thames and Hudson, 1991, p. 229.

Vincent Buranelli, Gold: An Illustrated History. Maplewood, NJ: Red Dembner Enterprises Corp., 1979, p. 204-205. Buranelli includes an excerpt from the 1847 text The Conquest of Peru by William H. Prescott. Prescott here relates the tale of King Atahualpa of Peru who offered gold and silver to Pizarro in order to save his life. Pizarro accepted the ransom which included many exquisite objects such as an ear of Indian corn "…in which the golden ear was sheathed in its broad leaves of silver, from which hung a rich tassel of threads of the same precious metal." However, in order to ensure a fair division of the treasure, the assembled objects were melted down "…to ingots of a uniform standard…." One final note, such generosity did not spare Atahualpa's life; he was executed in August of 1533.

Fagan, p. 176-177.

Maclaren, p. 616.

Maclaren, p. 632.

David Williams, The Georgia Gold Rush. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1993, p. 8.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

See Williams p. 9 for complete information.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., p. 11-12.

California: A Guide to the Golden State. New York: Hastings House, 1943, p. 690. While the discovery of gold in California is traditionally credited to Marshall, the United States government knew of the existence of gold in the American River as early as 1841. In fact, in 1842, twenty ounces of gold dust were sent to the Philadelphia Mint from California.

As a result of the Mexican War, present day California and other western states were ceded to the United States in 1848 by agreement of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo for the purchase price of $15 million.

Joseph H. Jackson, Editor, Gold Rush Album. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1949, 22-23; p. 165.

Edgar W. Morse, editor, Silver in the Golden State. Oakland California: The Oakland Museum, History Department, 1986.

Information regarding the history of the Aldermen medallions was kindly furnished by Rob Krulak, Dept. of American Paintings, M.H. deYoung Memorial Museum.

Evans, p. 9.

Buranelli, p. 72.

For a discussion of "goldfields" jewelry from Australia, see A. Schofield and K. Fahy, Australian Jewellery, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1991.

Buranelli, p. 89.

Buranelli, p. 96.

Buranelli, p. 110-112.

Our thanks to Karl Gurcke of the National Park Service who brought the pin to our attention and supplied the photograph and other pertinent material.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.