Hermann Jünger: German Goldsmith

9 Minute Read

From 1988 to 1989, German goldsmith Hermann Jünger was celebrated in his native country with a major retrospective of his work since 1945. More recently, in the spring of 1990, a new series of necklaces by Jünger was the subject of an exhibition at Jewelers'werk Galerie in Washington, D.C., and Spiros and Gretchen Raber, both of whom studied in Germany, discuss their views and interpretations of the importance of Jünger's work and thinking in the field of jewelry and goldsmithing.

"The original meaning of the goldsmith was to be found in his being both a creator and a craftsman: a man whose activities necessarily united both head and hand into a comprehensive unity. He made his plans, drew his designs, and executed them in metal himself. This was a man who combined the two great human possibilities — Thought and Action — in one creative profession. He was a unified, un-split person, and in this unity he found the meaning and harmony of his existence."

I would like to address the work of Hermann Jünger from the position of having studied with him at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Munich Academy of Creative Arts) for two years (1983 - 85). It was a very different experience than I was used to, requiring almost two full semesters of conceptual investigation before being allowed to make a piece of jewelry. An unlearning process, perhaps, of my four-and-a-half years of training as a metalsmith in America, it was, nevertheless, extremely beneficial. Jünger believes that studying goldsmithing at the Academy is not a training, but rather an opportunity for self-development; it is an offer of study as an experience of freedom. I was to collect, compare, contrast, compose and collate anything that would give me a clear idea of what qualities I was looking for in my work — before attempting to make it — a frustrating path to edification that proved invaluable.

It is itself an education to see Jünger work. For the short time I assisted him in his studio, I gained a tremendous understanding about his approach to making. The attention paid to (what seemed to me) an inconsequential aspect of a piece seemed inconceivable at first. But then I came to realize that the intrinsic value, the preciousness of the piece, was a result of approach, and thus I learned a great respect for nuance. Jünger would stand away, on a chair or across the room, looking at the piece from different angles, only to return to it, adding the final touches in an almost arbitrary manner — using gestures like those of a Neue Wilder abstract expressionist.

This is also how Jünger looks at work in general. During his last visit to New York this year, with his wife, Jo, he broadened my appreciation of my neighborhood, both from an architectural as well as a sociological standpoint. Then, as has happened in the past, I was enriched in the same manner by his observations of our trip to The Brooklyn Museum. I had scrutinized the museum's Egyptian collection innumerable times; but this time, when we stopped to rest, Jünger mentioned one very small, yet consequential object, a glass amulet in the form of two fingers from the Nile at Thebes (664 BC-525 BC).

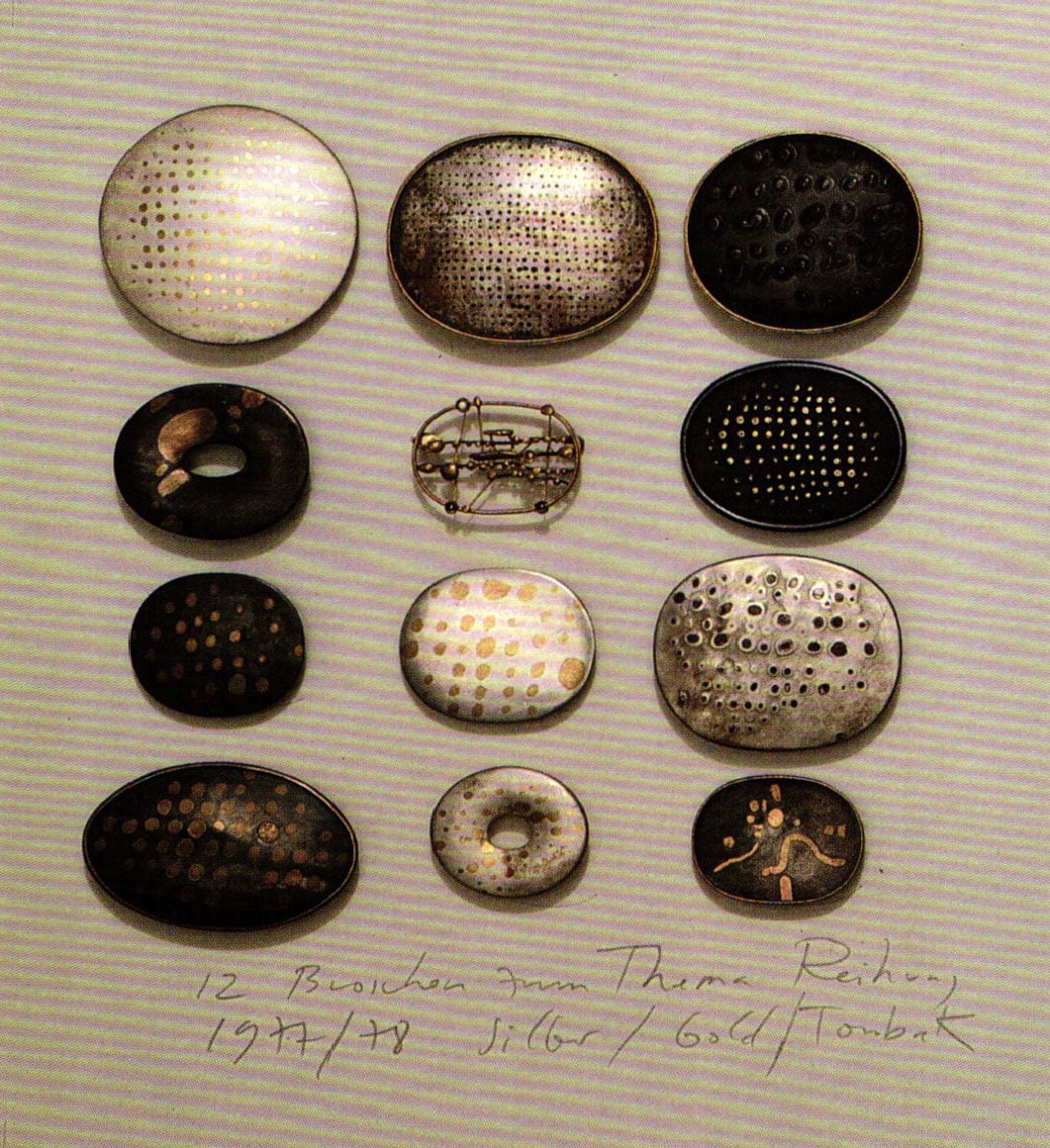

The piece was atypical for the period, yet, quite frankly, I had overlooked it. Another observation he made was of a tomb relief from the Nespeqashuty of the same period, the influence of which is found in his own early work, such as the brooch series from 1977-79. There were paint and scratch marks around and over the reliefs (only parts of which were carved completely), pious graffiti in Demotic and Greek left by ancient visitors to the tomb. As Jünger was reading the description, I realized that his work conveys the same feeling of cultural imprints as did the relief. His quest is knowing for what reason? by whom? at which time? for what means and to which end? a piece was made, not whether it solely pleased him esthetically. Underlying his apprehension is an insatiable desire to assimilate the cultural and social beliefs of the makers and users, regardless of what he is looking at.

In the context of his own work, Jünger describes the influence of growing up in a city (Hanau, Germany) with a very old tradition of gold and silversmithing. In 1947, he attended the Staatiche Zeichenakademie Hanau (Drawing Academy, Hanau), where he studied painting and drawing. Because of Hanau's heritage, even the fine art disciplines at the academy related to goldsmithing.

This was a very difficult time in postwar Germany, especially for someone trying to pursue goldsmithing. Classes were held in the basement of a bombed-out building. There were no tools, no workshops, no materials…nothing but devastation. However, Jünger, still only 19 years old, could see something positive in this — he was then able to concentrate more on painting and drawing. "We went out into the ruins and started making drawings from them. I didn't work in metal, there was none…Then we started to dig out the tools from the ruins and copper from the broken down houses."

Although the students could now begin raising copper bowls, etc., Jünger did not consider this serious goldsmith's training. He went to study with Franz Rickert at the Akademie den Bildenden Künste (The Academy of Creative Arts) at Munich, where Jünger himself began teaching in 1972. It was under Rickert that Jünger realized his real potential in painting, which cast doubt about continuing to be a goldsmith.

"Goldsmithing for me is very closely connected to drawing and painting (for me still), the first possibility to express something that I like to do."

Jünger explains that the rudimentary reason for continuing as a goldsmith was safety, not commercial safety but safety in the boundaries of the craft. When asked if this was more a limitation, he answered: "For me, I think it was a help, because the size is limited by the necessity of wearability. It has to be in connection to the body…I'm interested in a small format. Historically, things can be concentrated into a very small size and in spite of this be very powerful."

In fact, the strength of Jünger's work comes from his ability to translate with great articulation the emotion and spontaneity from his drawings into his jewelry. He uses them as "maps" to achieve the compression he finds synonymous with jewelry's success. The signature style of his drawings evolves seamlessly from paper to metal, with little apparent hindrance in the shift of materials.

Maintaining the mood of the drawing in a jewelry piece through its laborious processes is very difficult; but this difference never becomes evident in the finished piece. He explains that there are unknowns; because of all the procedures, you can't always control your progress, so it's still spontaneous.

Jünger's impetuous transcriptions are evident in his capriciously laid charm pendants positioned over loosely gestured watercolors. This jewelry is born from a chaotic conflux of minutiae that are precise dislodgements from the metals' fossil-like surface, pitted as if from decay. Here the boundaries of fine art and craft are overcome, not from the ability to translate one to the other, but because they elicit the same response. The medium is handled with emphasis on emotion, not technique. Jünger never considered himself a craftsman; this was not his concern, no pedantics. "Perfection is the opposite of the intention in my work." The objective in his work is to discover a certain quality, for instance, of that found in ancient pieces, enduring and lasting.

Jünger cites the Romanesque period as an example. He tells of a particular piece, in high-karat gold and enamel, that had been restored in the Erfurt Museum, East Germany. Except for the damaged portion, it consisted of geometric forms with a freely crafted imperfect circle. The man commissioned to repair it restored it to a perfect circle. The result was completely different, dead and sterile. Jünger explains that "maybe this is a condition of the old pieces, that they are not perfect, and while some jewelry needs an unbelievable amount of precision to exist, i.e., that of Friedrich Becker, there is another category of jewelry that starts to live because it doesn't have this perfection — what makes one piece live makes another die."

As a pastiche of African motifs, Jünger's gold necklaces exemplify, his "unfinished" program. The elements in the necklace are removable, allowing the wearer to compose his own medley of forms. The options are numerous: punched gold discs, ivory and enameled charms, gilded spicula and wires give a feeling of tribalism, where arrangement signals culture and distinction.

In curious contrast to his jewelry are Jünger's objects. Clean, stark lines circumscribe these pure geometric forms. Virtually no surface treatments are applied to the minimal forms, reminiscent of Brancusi's sculpture or industrial routers. The painterly qualities that Jünger incorporates so successfully in his jewelry do not find their way into the freestanding objects. He prefers to keep these simple and concentrate on their forms alone. Jünger suggests that in medieval times and later, in the Baroque period, people found ways to integrate color and ornamentation but he can't cite an example of contemporary work that is similarly successful. "Form follows function is much more convincing than trying to make a conversation piece in regard to objects."

"For Jünger, the formulation of his real function would be creating art for the human body. His work in the form of detached, free objects does not assume the full importance it always has when it is intimately related to a human being. It is exactly this field of tension between beautifully shaped objects and their function as signs worn on the body that Jünger searches for his art solutions."

Notes

- Hermann Jünger, 1979, quoted in "A Goldsmith's World," Art Aurea, 1/89, p. 58.

- "The Goldsmithing Class at the Munich Academy of Creative Arts," Art Aurea, 1988.

- From the description of the Nespeqashuty Tomb at The Brooklyn Museum.

- From an interview with Lisa Spiros, August 5, 1988, Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Munich (translated by Lisa Spiros).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jewellery as a Sign Language: The Work of Hermann Jünger, catalog of the exhibition at Galerie am Graben, Vienna, Austria, October 12, 1987 — November 7, 1987, p. 83.

Lisa Spiros is a jeweler living in New York. She is an instructor and coordinator of the metals program at the Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Related Articles

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.