The Impulse in Contemporary American Metal

34 Minute Read

For most of this century, story-telling in art has been considered taboo. From the turn of the century to well into the 1970s, Modernist tradition encouraged instead the investigation of form for its own sake. Art about art was the saluted inquiry and formalist critics denounced narrative content as excessive and indulgent. But in recent decades, artists in all fields have begun to insist that art and life are nor unrelated, that art is in fact nurtured by the personal, and these artists have sought to instill their work with the passion of their lives. Narrative has re-surfaced in contemporary art as one means of doing this.

What is narrative?, when is it present in art?, and why does it matter? Literary theorist, Roland Barthes, has written in his Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative.

"the narratives of the world are without number. In the first place the word 'narrative' covers an enormous variety of genres which are themselves divided up between different subjects, as if any material was suitable for the composition of the narrative: the narrative may incorporate articulate language, spoken or written; pictures, still or moving; gestures, and the ordered arrangement of all the ingredients: it is present in myth, legend, fable, short story, epic, history, tragedy, comedy, pantomime, painting,…stained glass windows, cinema, comic strips, journalism, conversation. In addition, under this almost infinite number of forms, the narrative is present at all times, in all places, in all societies; the history of narrative begins with the history of (hu)mankind; there does not exist, and never has existed, a people without narratives."

The challenge in understanding exactly what contemporary narrative art is, lies in deciphering how it is different from narrative art in the past, speculating as to why it has recently resurfaced, and in recognizing its presence and significance in a post-modern culture that perceives time, space, meaning, and communication far differently than the way they were perceived a century ago.

Basically, narrative art is story art. It is the act of telling a story, not merely creating a figuration of real life. Contemporary linguists, semioticians, philosophers, and critics have all attempted to define exactly what constitutes a story or an event! as they have de-constructed the notions that have previously shaped the way we think about reality. Gerard Genette has written that "…as soon as there is an action or event, even a single one, there is a story because there is a transformation, a transition from an earlier state to a later and resultant state." Though transformation implies progression over time, long-held ideas about the nature of Time, both "psychological" and "empirical", are also undergoing dramatic change. Traditional narrative structure assumed Time was a linear phenomenon with a single direction, in which events from the past cause circumstances in the present and set a direction for the future. If one thinks of a narrative as a series of events which take place over time, and which are structured by a beginning, a middle, and an end, one is assuming a causal chain of events, in which we are moving from the past, through the present, and into the future. But if we are able to understand time as being something other than a trajectory, then the idea of events taking place over time has a different meaning, progression does not exist, and narrative can be a quality of thought, as well as of action.

In contemporary narrative, artists address the complicated relationships that exist both on a personal as well as a socio-political level. We witness work that speaks to common myths, ethical dilemmas, and changing human values. Contemporary narrative art assumes three related, but different structural formats: the allegory, which relates one story under the guise of another; the serial structure, in which individual parts are lined up to form a single story or piece; and the use of words or text with images, to tell a literal story within the work of art itself.

Allegorical narratives are stories which signify something entirely different from that which they represent. They are extended metaphors in which people, things, and happenings have meaning beyond their literal presence. Fred Woell is one of the most significant advocates of the allegorical impulse in metalsmithing. Beginning as early as the mid-sixties, Woell has drawn heavily from popular images in American culture, orchestrating these images into jewelry, objects, and sculptures that sharply comment on the human condition. He is one of contemporary metalsmithing's first allegorists, adding new meanings to images that are familiar to us. He piles fragments of American icons upon fragments and he combines scraps of material culture and creates a weedy, cluttered story line. One characteristic of allegory is its use of the fragmentary, the partial, and the abridged in arrangements that must be decoded or transformed. Twentieth century theorist Walter Benjamin comments on the heroic gesture of allegory to "rescue" lost or discarded bits of information for "eternity": and, as also pointed out by Craig Owen, on the "common practice" of allegory "to pile up fragments ceaselessly, without any strict idea of a goal." Fred Woell selects the components of his work from the trash-heap of America's consume-and-discard economy, weaving allegories that shock through humor, catching viewers off guard. Narrative force guides his hand in the making of the work, and form comes into being as the story is told. His constructions allegorize with wit and wisdom, steering clear of conventional symbolism.

In discussing allegorical narrative, it is important to differentiate between the allegory and the symbol. Allegories easily lend themselves to narrative, but symbols do not. The words "symbol" and "allegory" are similar, but the two are hardly the same thing. The reason for the confusion is that symbol and allegory, being conceptual pairs, have much in common. Both have meaning or significance beyond external appearances, with one thing standing for another; both are means by which the non-sensory is made apparent to our senses, and both make a connection between the visible and the invisible world. But there is a crucial difference in how each comes to have meaning. The symbol is rooted in visual reality and is specifically derived from that to which it refers. Obvious examples are the symbol of the wedding ring for marriage, or the flag for patriotism. Symbols are, on one level, the essence of something - a particular part of the whole, to which the whole can be reduced. Allegorical meaning, however, is added or signified meaning: for example, the constructed relationship between Venus and romantic love. Allegories existed in Medieval theological teachings and provided specific information about Christianity to the masses; but their specific meanings were supplementary, interpretations externally applied onto a visual image. Allegorical meaning is signified, layered onto an image, rather than produced by the thing represented.

Like Fred Woell, Robert Ebendorf also orchestrates familiar bits of popular culture in his narratives, and Ebendorf too, avoids conventional symbolism. His jewelry and sculptural reliefs are allegories woven from strands of American culture and the details of personal confession. My Brother and I pairs the portraits of two young men within the framework of a tiny electrical switchboard. One man's head joins his reposing body in the lower half of the piece, but the other portrait remains a bodiless face. Their relationship is complicated; they are together, yet separated, complete, yet incomplete. The artist draws us close through commonplace images with which we are familiar, yet his narratives remain strangely distant and private. Even in his most recent work, his pieces are like the pages of an intimate diary that are written in a foreign language, confounding our reading.

Allegories often refer to intangible forces in our lives - good, bad, love, truth, and luck, to name a few. Alan Burton Thompson is a storyteller bearing witness to the perturbing as well as the pragmatic nature of these issues in our lives. His brooches incorporate colorful, mysterious, charm-like elements into surreal microcosms of fantasy and whim. The work, he says, is about heroism, medals, awards to us all, as survivors of the complex, frightening, exciting, and sometimes difficult art of living our lives. He feels these brooches are reminders of the values that help move us through obstacles and ignorance, toward a richer human biography. In his work, there is an unspoken plea for a return to humanistic issues which, for decades, has been absent in art.

Historically, allegory has been rhetorical and exact in its meaning, and has relied on convention for understanding. But contemporary allegories, such as Thompson's, are read less specifically. The development of a more open-ended interpretation in narrative art had its origins in the eighteenth century, when during the Age of Enlightenment new ideas caused the rejection of dogmatic tradition in favor of interpretive thinking and personal experience. Enlightened thinkers believed that the pedagogy of Christian allegories were, in fact, no more than priestly contrivances designed to control and manipulate the common man. By extolling a more personal translation of all things, including allegories, Enlightenment thinkers were freeing themselves not only from convention, but also from intellectual and physical domination. And even though interpretation may be less exacting in contemporary allegory, an understanding of the rich meanings and significances which allegories offer still demands the participation of an informed viewer.

When looking at Thompson's jewelry, one must be willing to experience the joys and sorrows in their own lives in order to come close to understanding the point of the works. But there is no hierarchy that exposes the logic of the stories. There is no beginning, middle, or end that tells one what is happening. Rather, the works are ordered in such a way that a story forms itself around the piece, rekindling the allegorical impulse with a touch of free-thinking and irony.

In recent decades multi-cultural and feminist art movements have insisted that the personal, the social, and the political are relevant, even essential issues for artists. These movements have been an important impetus for the re-introduction of allegorical narrative in contemporary art. Of equal importance is the fact that feminist agendas encourage the re-evaluation of art history, in order to include the missing pieces of information about women, people of color and oppressed classes. History and storytelling are traditions that are essentially different from each other. History reduces large tracts of human activity into convenient, symbolic bits that are strung together in a purposeful way to imply a continuous whole. Storytelling, on the other hand, works in an allegorical rather than in a symbolic way, implying larger and more inclusive meaning. As Gertrude Stein stated, "narrative concerns itself with what is happening all the time, history concerns itself with what happens from time to time." While both men and women have always told stories, it has only recently been acknowledged that women have also written history. Critic Lydia Matthews writes that it has been implied that "storytelling and History are sexually specific practices: women tell stories and men write History. While these activities are hardly as gender specific as the word (History) implies, it is true that narrative art has played a minor role in Modernist art history… Formalist critics had little patience for storytelling in art; not until the pluralist discourse of the 1970s and 1980s did the art of personal experience become a viable way to address the radical shifts in gender and ethnic identity that were recurring internationally."

Susan Kingsley is a feminist artist whose allegorical forms are defiantly personal. She uses floral imagery in her jewelry and sculpture, paying homage to this traditional woman's subject matter as well as using it as a metaphor to question culturally conditioned assumptions about women. Kingsley's flowers are larger than life. The images are derived from exotic orchids and carnivorous plants and are stylized in a way that references the organic forms and conspicuous scale of Art Nouveau. These are not symbolic appropriations to enhance formal issues, rather they are historic references that enhance the allegory. Kingsley's brooches are meant to call attention to themselves when they are being worn and to confront comfortable ideas about jewelry when they are being exhibited as objects. She states that her flowers are neither saccharine nor sentimental, nor are they decorative or precious. While they may seem erotic, enticing, and beautiful, they also embody a silent menace. Their intention is to lure, to captivate, and to devour. Their aggression is quiet deceit. An essential part of the allegorical in Kingsley's floral imagery is the fact that the pieces are wearable. As viewers we synthesize what we already know and accept about benign corsages, and the sentimental flowers historically used for jewelry, with our perceptions of these more aggressive blooms, forming a new narrative that allies femininity with power.

Often in contemporary allegory we are offered the content of the story in a fragmented, non-sequential way, as in the sculpture of Harriete Estel Berman. The absence of a specific story line leaves the text purposely open for interpretation by the viewer, suggesting, perhaps, that more than one explanation is possible. There is no one, specific truth. Berman's work, which she ironically refers to as Pedestals For Women To Stand On, are fabricated from printed steel doll houses, cut and rearranged according to traditional quilt designs. Berman's work exaggerates stereotypes of "womanhood" while informing us of the complex, chaotic web that forms any human being's existence. Our point of entry into her twelve-inch microcosms is dependent on our perspective, both psychologically and literally: because the form is a cube, we are prevented from absorbing all the information at once. We may enter at the beginning, middle or the end of this tangled sequence, and our understanding of it is greatly influenced by our own personal experiences.

Bruce Metcalf employs the irony of caricature in his miniature vignettes. He structures his allegories in a conventional way, with subject, object, and verb interacting. The plot is on the surface and readily accessible, speaking directly to the angst of everyday existence. One of the roles of contemporary narrative is to reflect on the complexity and confusion of urban-industrial culture. Metcalf does this by appealing directly to our unconscious, touching our most basic fears and desires. His brooches are mirrors which reflect the stories of both the viewer's and the maker's anxieties of living in today's world. The artist hopes to balance these deeply felt and, as he terms them, more horrendous maladies of existence, such as death, pain, and alienation, with the absurdity of humor. Another aspect of narrative in Metcalf's work is suggested by his compositions, which are much like isolated frames from a film, with characters caught mid-motion, mid-action, midway through the plot. The fact that freeze frames are one of the most familiar ways that visual images refer to larger, more inclusive stories, allows Metcalf's allegories to speak directly and openly and in a language that is more easily understood.

Action over time is the essence of traditional narrative, and it is also the point of Myra Mimlitsch-Gray's kinetic Timepiece brooches. Both the "empirical" time of the external, physical world and the "psychological" time that exists as a part of human perception can effectively produce a narrative. Mimlitsch-Gray's pieces employ traditional jewelry materials in non-traditional ways. Diamonds are used to exemplify their physical properties as abrasives, shifting the focus from what the stone is, to what the stone does. In Mimlitsch-Gray's brooches, diamonds mounted in small pendulums move back and forth across watch crystals. The body supports these pieces as a pedestal, but it is through the movement concomitant with wearing that the swinging stones carve a path into the glass, precisely scratching away at the vulnerable crystal beneath. The pieces form and re-form themselves over time. The passing of time is one of the strongest narrative devices in literature, film, and theater. In visual art, however, events are often compressed into a single image that becomes the evidence of something that has already happened, or something that is about to take place. Mimlitsch-Gray avoids such traditional plot structure in her work: her brooches are not illustrations of an event, they are the event itself, occurring over and over and over again. As her Timepieces slowly etch away at themselves, there is the suggestion that time, which was constructed as a way to measure and regulate our external world, may, in fact, be far more controlling of us than we are of it.

The resurrection of the historical is a strong allegorical impulse. Through allegory, artists acknowledge both our distance from the past and the transience of things, and they attempt to redeem what might otherwise be lost in oblivion. Martha Glowacki draws extensively from the rich, narrative tradition of the nineteenth century in her work. While dealing primarily with personal growth and psychological introspection, her pieces are also a response to nineteenth century engravings of vineyard and fruit tree cultivation, developing an allegory which suggests that nature's wisdom can inform human awareness. Contemporary artists find value in historic imagery, but many, like Glowacki, infuse it with personal meaning. This is a clear distinction between contemporary work and narrative art of the past. Paul Schimmel, curator of the exhibition American Narrative/Story Art: 1967-1977 has discussed this difference:

"It has been in the nature of art for thousands of years to tell or narrate an event of historical, religious, personal or political nature. From the earliest forms of pictorial story writing…the content was controlled by patronage, but the form was left essentially free. This emphasized the split between form and content that always characterized narrative art - the very schism whose absence anchors contemporary narrative/story art."

While Modernism eschewed content in art for the preeminence of form, Postmodernism heralds the retrieval of the spirit of content in form, a retrieval that links art to life and life to art. This infusion of content in contemporary art characterizes not only allegory, but also other ways in which contemporary narrative is structured.

Most visual artists who work within an allegorical framework compress time and events into a single image. Another aspect of contemporary narrative is the series, where individual parts come together to form a single piece. This kind of narrative has a format that has a forked root, so to speak. It draws both from the historical understanding of narrative as one event that follows another, and also from today's "postmodern" preoccupation with taking elements apart, extracting them from the whole, and analyzing them as individual components. In a series, narrative is revealed in the order, duration, and frequency of the individual parts. Roland Barthes points out that to understand this kind of "narrative is not merely to follow the unfolding of the story, it is also to recognize its construction in 'storeys'," as if one were moving through the stories of a building. To read a serial narrative is not merely to move from the meaning of "one word to the next, it is also to move from one level to the next."

Many artists extend their narrative images into a series of component parts, to heighten the viewer's experience of the unfolding story. Mary Anne Papaneck-Miller's enumerated brooch sequences are melancholic, unpretentious statements that identify her concern for a range of social and political issues. The square format of each brooch in the various series alludes to common methods by which narratives are often revealed, such as photographic images, books, and even television. Though the sequencing of images strongly evokes a narrative, the work does not intentionally reveal a plot. The compelling aspect of this jewelry is Papaneck-Miller's metaphoric use of the visual structure itself: within each of the "freeze-frames" she extracts noun images from the logical sequence of a plot structure and disposes them randomly within the tiny picture plane. Her idiosyncratic organization counters logic in the spirit of Magritte's surrealism. As viewers, we feel encouraged to decipher these narratives, but the pieces remain poignant questions.

While Kate Wagle's recent work is allegorical, it also uses a serial structure to convey its meaning. Images of Perfection is a series of individual pieces which develop into a kind of poetic allegory when they are mounted on the wall, side by side, in the linear installation that the artist intends for them. In this work, Wagle immortalizes familiar images that we either think of as having a short, perfect moment of duration, like the peak point of a dive, or, in the case of the diamond, as an object that lasts forever. Often artists purposefully use familiar images that we either think of as having a short, perfect moment of duration, like the peak point of a dive, or, in the case of the diamond, as an object that lasts forever. Often artists purposefully use familiar and commonplace images in their allegories, specifically because they imply a multitude of meanings. Craig Owen writes that "allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery. The allegorist does not invent images, but confiscates them." The allegorist, in many ways, is an interpreter. Wagle suggests that solidity and fragility often coexist. The culminating object in this series is a formal and imposing 24k gold sheet. It is all substance with no image, and seen in the context of the other images, it challenges our basic assumptions not only about what we value, but of how we have come to value it.

Many artists use the series in an accretive way, building narrative meaning as individual parts add up to a whole. Often the meaning of one piece can only be inferred by viewing it in the context of an entire series. Jill Slosberg-Ackerman's Living in Two Worlds is an ongoing series in which she explores dualities. The first pieces in this group, she explains, were made in 1981 after hearing art historian Leo Steinberg discuss a Picasso self-portrait, in which the head is conveyed in the round even though the painting as an object is obviously flat. It occurred to Ackerman that adornment could be rendered more meaningful if earrings ceased to be a matched pair, and were instead two separate objects which refer to each other, and complete an idea. Her pieces, in either parts or trios, are metaphors in the larger narrative of the on-going series. Such an extended work, expands that artist/viewer interaction greatly over the interaction afforded by a single image.

In Susan Hamlet's brooch series, each separate unit has meaning, but viewed in sequence, they push us to assume a larger narrative. The series Four Seasons, made of gold and lead, juxtaposes an exterior, dehumanized, robot-like form with varying interior cutouts. The changing forms inside each piece represent a growing, developing, interior self and a personal evolution which parallels the cycle of the seasons. Beginning with Fall, the cutout is a fissure. It becomes a ghostly apparition in the second brooch, entitled Winter. The internal shape evolves into a transitional figure in Spring, and finally emerges as a tentative young woman in Summer, the last brooch in the sequence. Another series, Basic Math, collectively forms an equation, utilizing mathematical symbols in the interior to represent the systems which standardize, clarify, and, ironically, confound our lives. One paradigm for narrative work is the mathematical progression. As Angus Fletcher writes:

"If a mathematician sees the numbers "1","3″,"6″,"11″,"20″, he would recognize that the 'meaning' of this progression can be recast into the algebraic language of the formula: X plus 2″, with certain restrictions on X. What would be a random sequence to on inexperienced person appears to the mathematician a meaningful sequence…This parallels the situation in almost all (serial narratives)."

Shari Mendelson uses a number of structural devices for her narrative effects. At a basic level, she reduces elements to pairs, encouraging a dialogue between them. In some cases the elements are mirror images, conversing in their mutual isolation. In other pieces, Mendelson matches a form with its opposite, or several other counterparts, suggesting the necessity for difference in arriving at harmony. In the installations Calendar and Sins, she abandons the structure of sequence for a more complex serial structure. Both of these pieces repeat a single element many times and then these elements are arranged into a grid. The minimal changes from one element to the next encourages a careful reading of the entire piece to find the meaning of the narrative. A grid pattern is another method of recording time, and it is a way to allow the viewer to create his or her own time and order in their perception of the work.

Since narrative often comes out of structures in which one event follows another, as in film or literature, almost any sequence of images is capable of evoking a narrative. It is in this way that narrative can extend beyond representational and figurative imagery, into pure form. Such is the case in the work of Hai-Chi Jihn. In Jihn's work sequencing is sometimes ambiguous: a reading from left to right is as logical as reading from right to left. She may also direct us through a series of visual frames toward a projected goal, as in her sculpture Hopscotch. We move through this work in an immediate, visceral way, jumping visually from grid to grid, recalling our particular memories of this childhood game to which the title refers. Here, as in most work that uses a serial structure, the viewer is an active participant in the unfolding narrative.

The sequencing of information is a conventional narrative structure that has roots as old as Egyptian steles and Roman panel paintings. Narrative structures that incorporate text have a similarly long history. For centuries, artists have been combining words and images for a variety of purposes. From the wall reliefs of ancient Egyptian temples, to the inscriptions on the Column of Trajan, to the descriptions of the lives of the saints in Renaissance painting, and up to the words or word fragments in works by Picasso, Magritte, Duchamp and others, language has provided clues or context to the reading of visual imagery. With the profound infusion of printed media into contemporary life, artists of the past three decades have particularly used language and word imagery in their art as a way of bringing their works closer to contemporary, human experience. Much of this recent work examines the very nature of meaning and communication; some work investigates the relationship between words and their visual equivalents, and other works use a combination of the verbal and visual in a narrative way to tell a story or describe an event. Artists whose intents are narrative ones, may employ the conventional use of explanatory text with a sequence of accompanying images, or they may explore more innovative methods of revealing a narrative. Short captions and phrases that either augment and/or contradict an image, and the use of commands, directives, and instructions, all engage the viewer in the task of deciphering what has happened, what is happening, and/or what is about to happen.

In Jean Loy-Swanson's work, words and images are used simultaneously to form the narrative. Loy-Swanson looks to Medieval metalwork when fabricating her ornate, chain mail athletic supporters which are hung like trophies in shadowbox showcases. One word labels or short descriptive phrases such as "TIME" and "MAN OF THE YEAR" are incorporated into these mini-displays embellishing the pieces and recalling parade floats or amusement park rides. Standardized typefaces are transformed with colors of gala-red and gold. Loy-Swanson's narrative is not a specific story, but rather a generic, repetitious tale of victory at the expense of innocence. While these commemorative displays recall the ongoing human narrative of winning and losing, the historical reference to Medieval regalia also calls into question long held modes of oppression that continue to permeate the values of contemporary culture. The text and images in the works have a reciprocal relationship: the words, presented in standardized typefaces and glitzy colors, evoke imaginary scenarios of commemoration and institutionalization, while the sculptural Forms provide specific and literal references. In one piece, the phrase "To The Victor Go The Spoils" is printed over and over again, reiterating that this narrative of war, conflict, and domination repeats itself interminably, each time as energetically as if it had never happened before. The text in these works is not separated from the image as in the caption of a picture and the words suggest a specific reading of the piece, a reading that offers a humorous, almost sardonic interpretation of ever-repeating human tragedies.

In Asian art, the narrative tradition has often paired text with imagery. In Japan, for example, the "poem-painting" has been a tradition that has flourished since the twelfth century, when it first appeared. This narrative form commemorates particular events or stories by identifying the thoughts of the figures depicted within the paintings. Having lived several years in Japan, Harlan Butt finds particular influences in this long tradition. In genres such as the Japanese "poem-painting," each work had a specific intent, but in postmodern times, narrative is more likely to be idiosyncratic, laced with double meanings, and informed by the artist's personal experience. One of Butt's installations, entitled 10 Bulls in a Quantum Field, is a series of ten wall-mounted reliefs that combine the verbal and the visual in mutually supplemental ways. 10 Bulls… is Butt's interpretation of the 10 Oxherding Pictures, a traditional series depicting the ten stages of enlightenment in Zen Buddhism and a series that has been painted by many Asian artists. In Butt's contemporary interpretation, each relief has a resident text that reads as a poetic caption to the images. Image and text work together to reveal the story of the artist's relationship to his work and the specific nature of his creative process. As in his other work, Harlan Butt chooses a traditional narrative format to elaborate on the relationship of his objects to the rituals from which they are derived. The artist also serves as narrator of the written story. Viewers move on and out between the images and the text, which together create memory-filled narratives, that are poignant, meditative, and personal.

Pamela Lins explores a variety of innovative ways by which the combination of words and images can tell a story or describe an event. Often, the text is somewhat obscured and fragmentary as in Lins' dish stories, in which crater-like bowl shapes hermetically confine an array of visual and verbal information in various stages of decay. The collection of words and images inside the bowl's rim is offered randomly. We may arrange them into whatever narrative we choose, and we are free to change or reverse that order at any time, depending on the information we bring to the piece. Each viewer extracts new and different scenarios. In this work the text is used as an ambiguous element that produces a quandary, rather than using words as a clue for deciphering specific meaning.

In more recent work, Lins puts text against form, setting up incongruous relationships that prompt open-ended discourse as viewers bounce back and forth between word and image, image and word. Lins confronts us with a dissected syntax in Legal Alien. In the diptych, framed, copper vessels rest formally on pedestals placed in shadowboxes behind glass. The title floats authoritatively and imposingly on the surface of the glass, obscuring our view of the enclosed contents: "LEGAL" conceals a Western style cup and plate, while "ALIEN" shrouds a Greek amphora. Because the two words are separated from each other by the framing device, we examine both the phrase and its separate component parts. In addition we inevitably see the words in relation to the vessel forms. As we flip back and forth we are caught in a narrative suggesting ethnic identity juxtaposed against the myth of our culture as a melting pot. Both of these readings recall the personal and the public experiences of cultural transition. As in her other works that investigate the dynamic exchange between words and image, text spurs an on-going narrative in our minds as we compare, contrast, and scrutinize the relationships of the parts to the whole.

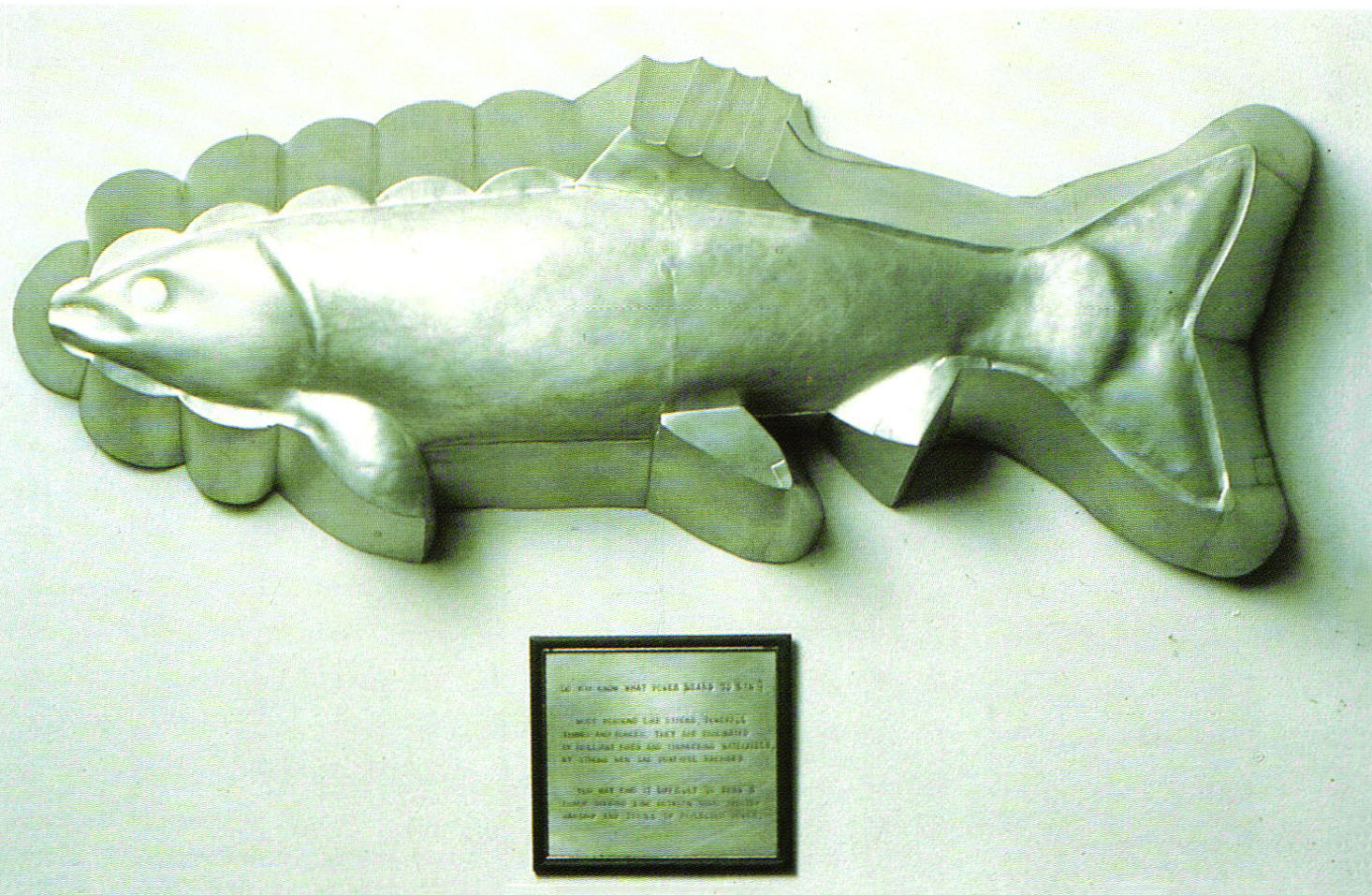

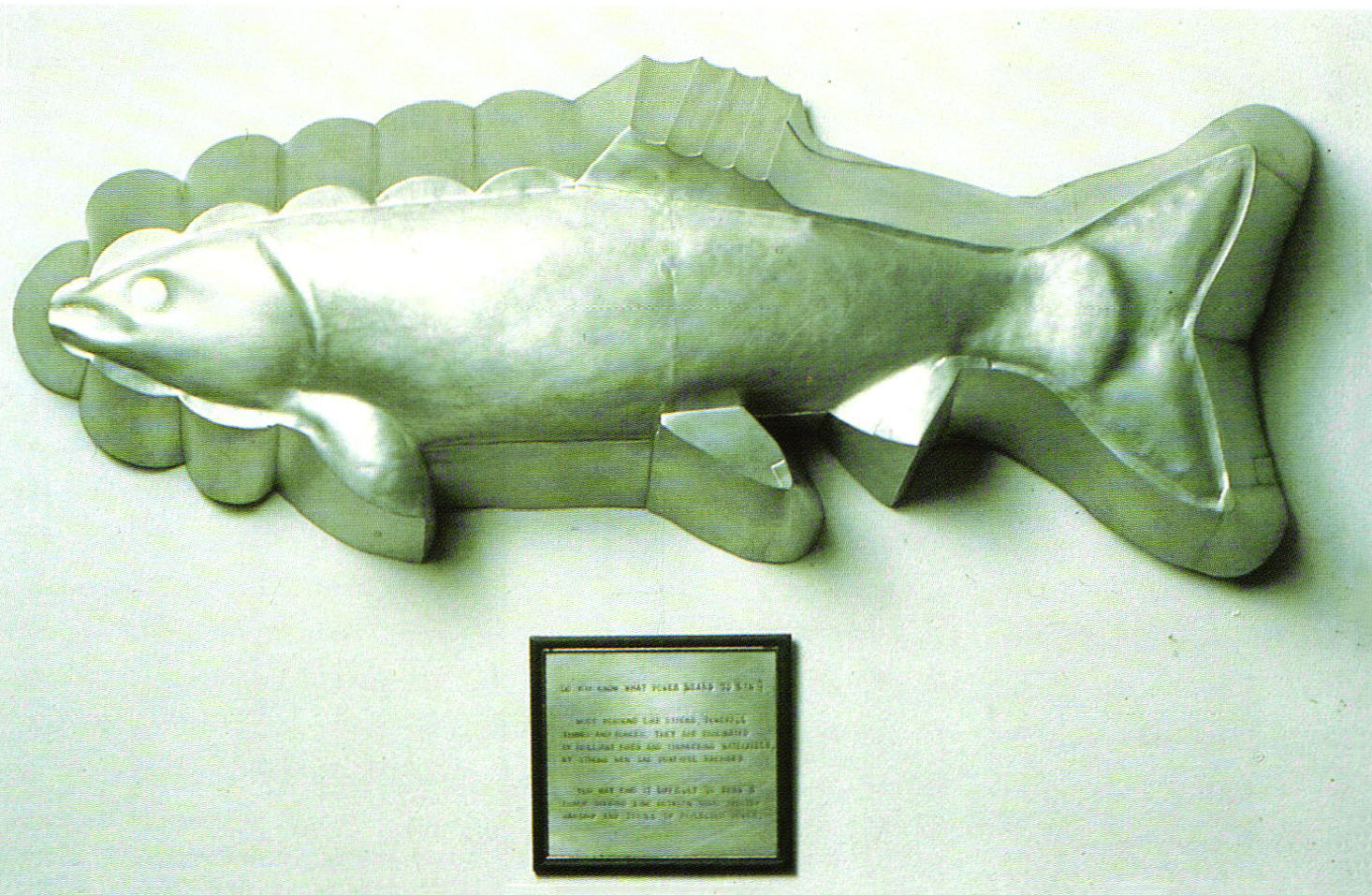

Text functions as a kind of narrative counterpoint in Lisa Norton's works, which the artist calls "projects". Each of her pieces pairs an oversized, but ordinary, utilitarian object, such as an umbrella, a pail, or a pitcher, with a framed, wall-hung image. Norton fabricates the objects in non-precious metals using techniques which originated in early industrial society. She constructs the wall images to resemble blueprints, rather than traditional drawings or paintings. Phrases and instructions are embossed on the sculpted objects and stenciled on the accompanying diagram, which is mounted on the wall behind the form. The diverse catalogue of quips and phrases that she pairs with each object calls into question the power of language to direct meaning and to influence the interpretation of visual forms. Each of the remarks paraphrases a stereotype of understanding, and each verbal gesture suggests a narrative, particular to the lifestyle that has informed that stereotypical point of view. The works are summations of a multitude of narratives, each narrative culminating in a perfunctory quip. Everyday assumptions and the absurdity of assuming and accepting succinct or specific definitions are the issues which Norton addresses.

Sportsmanlike Project is a sterling silver "trophy" in the form of a gigantic fish-shaped jello mold. Its accompanying text stares: "YOU MAY FIND IT DIFFICULT TO DRAW A SHARP DIVIDING LINE BETWEEN GOOD SPORTSMANSHIP AND THE THRILL OF REFLECTED POWER". "Is the narrative about ethics or abundance?", we ask. Studying Lost Time is an over-sized colander on which terse quotes are printed; such as: "LOST TIME OCCURS WHILE WAITING FOR SOMETHING TO HAPPEN" and "THE ANTIDOTE IS USEFUL OCCUPATION". The old wives tales, poetic clichés, and truisms that accompany this object reflect the myriad interpretations associated with such commonplace forms. These words also suggest the narratives of those that speak such clichés. Each object triggers familiar memories, and a second narrative, embellishing the first emerges. The objects Norton represents often enter the circuit of collectibles, and thus they are assigned a value disproportionate to their intrinsic worth, due to scarcity, impracticality or simply nostalgia. The value or meaning of the object is thus determined by context. Viewers identify with this assigned meaning by placing themselves in the particular narrative of whatever marketplace has assigned this worth. Though text embellishes these "projects", Norton's use of language is far from decorative. Instead she uses language to set up relationships which engage viewers in narratives that question the methods by which we prescribe meanings in life and in art.

Narrative art since the 1960s has been highly personal and emotionally charged. Kathleen Browne's jewelry is embossed with captions and appropriated texts that add additional narrative meaning to her already suggestive figurative imagery. "Last summer the fruit hung ripe and full and loosened to the touch" is the caption for a succulent but ambiguous, figurative form bearing pendulous breasts of dangling baroque pearls. The interaction of language and form suggests a specific reading of the narrative. Browne draws upon Medieval reliquaries as a source of inspiration. Her text is stamped directly and clearly onto the surface of the metal, recalling the outer surfaces of reliquaries which are embellished with the lives of the saints. High Tide, for example is in the form of a sarcophagus, a container similar to an ossuary. The inside container of High Tide holds what appears to be the remains of the body referred to in the anecdote printed on the lid. The passage states:

"My mother was told that she had been an Egyptian queen in a former life and that she had been driven to take her own life, by walking into the sea, as a result of a failed love affair. She met her former lover in this lifetime and they dated for awhile but the spark was gone."

The interaction of words and images in Browne's piece is a straightforward multi-telling of the tale. Though fictional, this artist's work is specific and personal. While it is possible for us to bring many of our own experiences to the pieces, Browne weaves viewers into the maze of her own particular dream-web. While her work touches on the bizarre and the fantastic, she is still a storyteller in the most traditional sense.

The resurgence of narrative in contemporary art follows no single rationale and no specific chronology, though there is a correlation between the concern with narrative content and the end of Modernism and its attendant avant-garde. "Modernism above all exalted the complete autonomy of art, and the gesture of severing bonds with society," writes Suzi Gablick.

"Today, remaining aloof has dangerous implications. We are all together in the same global amphitheater. There are no longer any sidelines… The old assumptions about a nuclear ego separating itself off from everything else are increasingly difficult to sustain in the face of our changed circumstances. Exalted individualism, for example, is hardly a creative response to the needs of the planet at this time, which demand complex and sensitive forms of interaction and linking."

It is understandable that because of the catastrophic events of the late twentieth century it is no longer possible to see history, or art, as a progressive process where the past is simply something to be overcome and the future bodes something better. In a kind of postmodern schizophrenia, the future looms dark and unclear and the past seems too unreliable to serve as a foundation. Deconstructing notions of the efficacy of the past and the future in the present situation, and evolving a new, less self-aggrandizing paradigm for the present is a primary concern of many contemporary narrative artists.

Narrative art in the postmodern age follows no credo of style or singular motive. It is essentially concerned with encouraging a broader understanding of art in its larger relationship to life, beyond pure aesthetics and the process of a hermetic art history. With its history situated within the applied arts, jewelry/metalsmithing, has always existed in the space between art and life, and the work of recent narrative artists in the field strengthens that relationship. The narrative impulse connects meaning to form, a meaning that is directly relevant to the issues of our lives. Above all, it tells us that it is still possible to find significance and compassion, as well as aesthetic substance, in the drama, pathos, and humor of stories.

Beverly Penn is a metalsmith living in San Marcos, Texas.

Notes

The author would like to extend special thanks to James Bennett for his editorial insight and encouragement in the development of this article.

Donald E. Polkinghorne, Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences (Albany, State University of New York Press, 1988), 14.

Gerard Genette, Narrative Discourse Revisited (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1983), 19.

Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. By John Osborne (London: New Left Books, 1977), 223.

Ibid., 178.

Gertrude Stein, Narration (New York: Greenwood Press, 1969), 30.

Lydia Matthews, "Stories History Didn't Tell Us," Artweek, no. 22 (February 14, 1991), 1 - 5.

Paul Schimmel, from the "Introduction," in American Narrative/Story Art 1967-1977 (exhibition catalogue), (Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum, 1977), 4.

Roland Barthes, Image - Music - Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 87.

Craig Owen, "The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Post-modernism," in Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed.by Brian Wallis (Boston: David R. Godine, 1986), 205.

Angus Fletcher, Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1964), 174.

Suzi Gablick, The Re-enchantment of Art (New York: Thames and Houston, 1991), 5 - 6.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Electric Kiln Fired Mokume Gane Part 1

Steps on Making a T-Fold Boat Fold

Kliar Vibrant Colors for Metal Jewelry

Causes & Prevention of Defects in Wrought Alloys

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.