Interior Motives

13 Minute Read

Myra Mimlitsch Gray's work encompasses a broad scope of social issues brought to light by an equally broad range of styles and techniques; but none are as they normally appear. The artist's work challenges our assumptions about the things we use in everyday life. Beginning with the common exterior of teapots, spoons, creamers, trays, and watches she explores the interior lives of the objects. A spoon may be split in two and embedded in a tray, or a box structure may hint at a teapot that can not be seen. While common objects do not usually engage us in their history or customs, they do sometimes draw our interest to the aesthetics of fashion or function. Mimlitsch Gray's skills lie in her ability to question the social contexts in which these everyday objects are imbedded giving them new dimensions. And though her work is produced in several series simultaneously, they are consistent in their social content.

Mimlitsch Gray received the traditional, technical training of a gold/silversmith beginning in 1980 at the Philadelphia College of Art, followed in 1986 with a MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Though, historically, women in the metalsmithing field were involved in the polishing and chasing areas and not smithing and forging, Mimlitsch Gray became adept at the full range of smithing techniques and, thus, moved beyond the restrictive traditions that had been in force up to the mid-twentieth century. The artist learned to create splendid functional metal objects that proudly exhibited their materiality and technical finesse. However, the pursuit of perfect surfaces and clever solutions to design and function began to conflict with the artist's desire to be more expressive. While polishing metal objects for the mass market at a small silver manufacturing firm in Philadelphia, Mimlitsch Gray became aware of the ways that competently designed objects were made more marketable by revisions from the marketing department rather than the design department. Gradually, Mimlitsch Gray began to look at the domestic objects themselves and to come to terms with their history, their tradition as symbols of prestige, and at how these items related to the role of women in a male-dominated culture. The works that resulted from his investigation exist largely in the context of a confluence of social issues that question class and domestic relationships, gender lines, and labor and business practices. Her materials and techniques are those of the traditional craftsperson and it is through them that she chooses to express herself within the evolving field of metalsmithing specifically, and the crafts filed in general.

Ambiguous and filled with tension, Mimlitsch Gray's Timepieces are the first she distilled into social commentaries. Built on the concept of a metronome, these kinetic objects keep time only when worn on the body, with the passage of time being recorded by a diamond set onto a meter bar which scratches a glass surface. Formalist in style and design, they have the scale of jewelry and are reminiscent of Margaret de Patta's ground breaking jewelry of the 1940s. With their limited life spans, it is material time that is gracefully and conceptually explored. Or perhaps it is a time that records the consequence of human actions as materialized through the movement of the wearer.

Mimlitsch Gray's hollowware series is one of her most challenging. Layer upon layer of visual experience is coupled with the social and domestic resonance of the chosen objects. In this series, salt cellars, bowls, teapots, and decanters are enclosed in both plain, nondescript boxy structures or in slightly curvilinear fabrications. Some of the encased vessels are found objects produced by industry, while others are reproductions of traditional vessels handmade by the artist. Each vessel is divided (sliced) in either halves or in variously sized segments. The viewer is left with a silhouette of a common object which flattens the representation. The encasement denies an ordinary visual experience of viewing the convex surfaces of volumetric form, and exhibits instead the recessed spaces of the interior of the containers. One comes to know such common vessels for the first time by their interior reality.

The encased Decanters and Salt Cellars are halved. When closed, the exterior silhouette shape is curvy and sensual; when opened the interior of the vessel is revealed and again one sees the original form and recognizes it by its silhouette and inner dimensions. The womb-like interior is a metaphor for everywoman. The decanters are handmade replicas of late 19th Century American wine goblets. The artist recalls the late Victorian Period, with its mixed messages and eclectic tastes, to comment on the roles women played in service to men: domestic servants, moral exemplars, Mothers, and paeans to chastity. Foregrounding the interior of the vessel, Mimlitsch Gray seeks to symbolize woman's inner being rather than accept the traditional prescriptions based only on her status and social roles.

The Encased Teapots are solid boxy forms with two or three small openings created by the tight cut of the surrounding encasement which slices through portions of the spout, handle, and lid. Through these narrow, sensuous openings, viewers can only peek into the vessels' interiors and see their bright and shiny silver linings. These very formal, almost minimalist objects depend on visual deprivation. By denying access to the form they tantalize viewers to speculate about the actual sensually suggestive shapes within. Through this subtle and ambiguous sexuality, the artist engenders a new level of inquiry.

In Encased Teapot, 1991 Mimlitsch Gray takes a manufactured teapot and places it inside a handmade box. She highlights the contrast between the austere design of a traditional Shaker object and the sumptuous shape of the teapot and the industrial processes which mass produced it and so many other duplicate forms. The Salt Cellars reflect the process of their manufacture as mold-made, machine-punched volumes. In standard industrially-produced cellars, the separate halves are joined during manufacture. Mimlistch Gray presents both mold and form to the viewers. These positive and negative shapes force a consideration of both the production process and the traditional use of such containers.

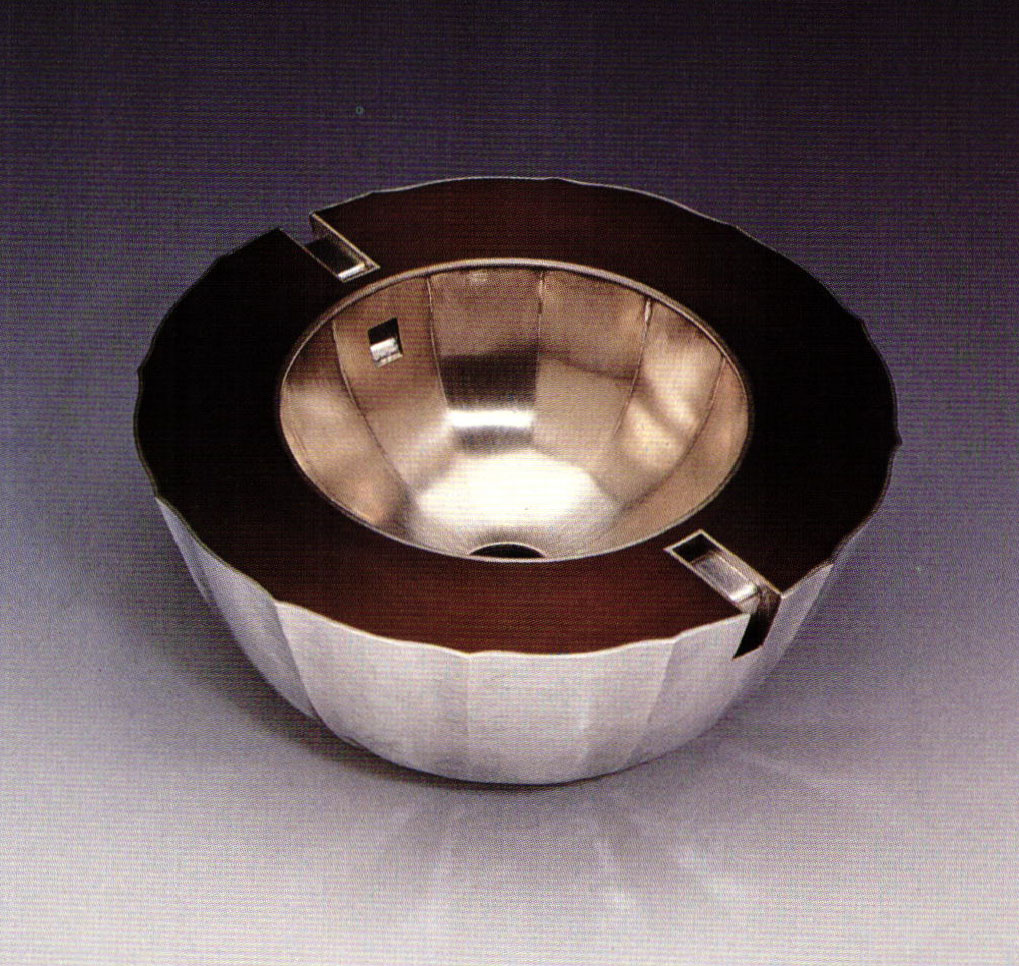

Presentation Triad is Mimlitsch Gray's quintessential vessel form. It is, in her eyes, a Tea Service, with a teapot, creamer and sugar. Their exterior forms are polygonal solids, yet, none have a spout, handle, or lid, nor are they encased. This set is the volumetric representation of the interior voids of these traditional, functional forms. As with the Decanters, the artist has given us an unexpected interior, solidified and faceted like a jewel. In addition, an almost obsessive application of felt pads, commonly used to protect table surfaces, covers the forms at their corners, so that no matter how the pieces are put down, no scuff will be made. This protection implies use, even though the tea and coffee services of today, particularly those made of precious metals, are rarely used. Instead, they tend to be for display as markers of status, wealth, and class.

The artist continues her investigations in a series of spoons, which have taken three forms. She has produced spoons as jewelry, embedded in plates, and in her familiar encasements. All three isolate only the spoon, knives and forks have not been treated. Mimlitsch Gray remarks upon her choice of flatware by saying, "The spoon is a sensuous form. It's both phallic and vaginal. I'm playing with its sexual identity and its innate romance."

Typically, the spoons are highly polished, yet split open, bent backward, and gracefully contorted. They are metaphors for women who contort themselves trying to fulfill the duties imposed by society. The bold, bifurcated spoons are presented as still lives, or, lives stilled. They are solemn, quiet, strong, and aesthetically elegant. Indeed, Mimlitsch Gray refers to these forms as "portraiture".

Issues concerning domestic roles are further explored in shadow boxes. The artist does not just call to mind the table as social setting; rather, her arrangements incorporate the special cloth sheaths and storage boxes used to house silver tableware when it is not being used. The elaborateness of these storage structures directly raises issues of wealth and prestige. One piece uses a box-like form in the silhouette shape of a hand mirror. The spoon is centered with the concave surface of the bowl occupying the same location where a face would be reflected.

Isolated pieces focus on a particular subject and can be quite Dadaesque in nature, taking a revealing and yet defiant tone, as compared to the relative simplicity and elegance of the work in series. One such object is Heels. Deceptively simple, this pieces is layered with histories and innuendoes that engage questions of gender conditions in the late twentieth century. Two stiletto heels lay together with corkscrews jutting out from the surface where the heel would normally adjoin the sole. Semi-precious stones are set at the tip of each heel. Perhaps a screw is needed to keep the impossibly tilted appendages attaches, or one could unscrew them and take them off the shoe. Mimlitsch Gray may be saying that a woman may be feminine in heels, if she wishes, but that they do not describe or define her, that she is now free to take her rightful place on the level ground, off the unrealistic pedestal of shallow praise and social expectation.

Many of the artist's isolated works resemble what the art historian and critic, Suzi Gablik, described in her book, Has Modern Art Failed? As "anxious objects", a term she credits to critic Harold Rosenberg. Gablik writes: "Faced with an anxious object, we are usually challenged, and may even find ourselves baffled, disturbed, bewildered, angered, or just plain bored. The difficulty is to discover why this is art, or even if it is art." As many of Mimlitsch Gray's artworks inhabits this territory, it is tempting to associate them with ready-mades and see them as merely contributing to the category of works influenced by Man Ray, Fluxus, Dada, etceteras. However, it is important to note that Duchamp changed the objects he found (or selected) very little, where Mimlitsch Gray dramatically alters her objects, or actually fabricates them in metal. More to the point, however, is how the artist's personal involvement in her object reflects a craftsperson's love of manipulating materials by hand, thus endowing the resulting object with a humanness gained from touch.

According to Gablik, most, if not all modern art movements over the past one hundred years were in reaction to a previous artistic practice. This continual assault on the past has left us no tradition to rally against; we are left only with ourselves. Mimlitsch Gray is fulfilling a promise of modernism in perhaps the only way left. As Gablik states: "the only legitimate strategy left to produce art in a Modernist mode is to use personal vision in order to deal with social responsibility."

Painters and sculptors have pursued their personal vision and questioned the traditions of their media for centuries, but it has been the rare craftsperson who has challenges the tenets of her or his field. As craftspeople increasingly break traditional boundaries and explore personal and social issues, the rigid definitions of art and craft are blurred, creating a dialogue between fine arts and crafts. Mimlitsch Gray's work serves as an excellent illustration of the work of a craftsperson engaged in social commentary and artistic exploration and collapsing the boundary between art and craft.

One of the strongest emotions the artist evokes through her objects is that of sentimentality. When this emotion is in play, contradictions seem invisible or unimportant as the viewer's response is primarily pleasureful. This is because some amount of myth and magic are at work. Why else would Victorian lives and lifestyles be so popular today? It is big business to encourage people to imagine living as in a romantic past, dressing up and playing the role of a Victorian, as witnessed by magazines devoted to a sentimental version of Victorian life. Yet, looking through this masquerade one may question how those estate lawns were so well maintained, how afternoon tea just appeared so magically at poetically gorgeous table settings, or how some could enjoy the weekdays while others labored in factories or in other countries to export the best of their material and labor. Mimlitsch Gray's use of objects that recall sentimentality is purposeful, as it lures viewers in and then hopes to redirect them into asking deeper questions as to how the world really works and what issues are really at stake.

Mimlitsch Gray evokes and mimics the 1970s when she uses found spoons as jewelry. During that period, sterling flatware was cut and bent into rings and bracelets; though, her heart shaped spoon and neckpiece, for instance, are almost too lovely to be thought of as part of that heritage. Aside from nostalgia, the artist's use of sentiment is more fully, even blatantly realized with the brief, concurrent series which she refers to as Baubles. The large heart-shaped Purge and Ring II, are tight, hollow constructions of tiny profiles of stars, horses, moons, and flags, all mass-produced in brass. Mimlitsch Gray refers to these as "images of Americana". Gold-plating creates a more precious object, imbuing a cute item with a deeper beauty. Yet, the beautiful heart, which would be perfect for Valentine's day or Mother's Day, is too large to be wearable, and it has no pin-back either, which diminishes the possibility of wearing this token of affection.

Ring II similarly captures the shallow beauty of Purge, but its shape is that of brass-knuckles. The elegant (gold-plated) form and gold-plated kitsch looks like Beverly Hills chic meets L.A. street reality. Although the image is one of power and implied pain, the reality of this ring is one of futility. Mimlitsch Gray has only constructed the hollow form; if used for aggression the object would collapse. It is therefore simply fashion, offering safety based upon appearance or image. Perhaps the artist is relating, through these Baubles, that the American dream, however wonderful in its complexity, promise, and potential, is, in fact, more fragile and delicate than perceived. And, given the extremes to which Americans are prone, from overeating oat bran to buying $200 sneakers, the dream, if tested too far, may collapse. Through these pieces we can see how Mimlitsch Gray's work operates on several levels simultaneously, exhibiting qualities that are at the same time intellectual and emotional while reflecting on obsessiveness prevalent in the 1990s.

In the artist's own words, her work "comments on the trivial, questions commercially generated symbols, and simultaneously celebrates the feminine, the sentimental and the craft".

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer, who resides in upstate New York. He is a frequent contributor to Metalsmith.

Notes

Personal information and quotes not otherwise cited specifically are drawn from conversations between the artist and author which took place during May of 1994.

Lilian Price, "When is a Chalice not a Chalice?" Arts Indiana, February, 1993, 26.

From a letter to the author by the artist, February 12, 1994.

Gablik, Suzi, Has Modernism Failed?, 1984. 36.

Ibid, 128

Cit. Mimlitsch Gray's letter.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.