The Intimate Abstractions of Rachelle Thiewes

19 Minute Read

The third week of October was, ostensibly, a week like any other. But in the art world, it was a wild week of almost deafening hype. There was coverage of the tedious back-patting that surrounded the opening of the new American Craft Museum. Concurrently, though widely unnoticed by the craft crowd, the art press was buzzing over the Sonnabend Gallery, which had piqued interest by showcasing four East Village artists, all under the age of 35.

These four had successfully sold themselves as a single entity to the most prestigious bidder and held at bay potential clients until the exhibition closed, at which time gallery and artists together would decide who was worthy of owning what! And then there was the long-awaited New Yorker profile of Artforum editor lngrid Sischy, which hit the stands sizzling with lurid tales of backbiting and acrimonious rumor.

Against this background of madness and mayhem. I prepared to interview Rachelle Thiewes, who came East from El Paso. Texas, to take part in the American Craft Museum's inaugural festivities. Throughout our sessions, Rachelle Thiewes emerged as a refreshing counterpoint to the publicity-hungry art world, an artist fully committed to finding and expressing her own voice. The manifestation of this commitment appears in virtually all her work as a unity of intention and form that could not exist if the artist allowed trends and tastes to interfere with that inner voice.

Rachelle Thiewes's early years were spent in the expansive landscape of the Midwest. She was born in Minnesota, grew up and attended college in Illinois and received an M.F.A. in metals from Kent State University in 1976. She moved to El Paso to accept a position as Instructor of Metals/Design that same year and has remained there, moving through the academic ranks to Associate Professor of Art in 1983.

Rachelle Thiewes realized remarkably early, during graduate school, that she was interested in addressing three major concerns: She is inextricably bound to refining pure formal integrity. She is also involved with the construction of form that "is to be applied and worn as an extension of one's physical self"; and, finally, she is intent on incorporating line and light to provide a whispered embellishment to her minimalist form. In addition, various themes seem to appear throughout her development, despite their absence in her formal agenda, specifically the use of movement to effect a musical quality in her pieces and an omnipresent sexual reference. What emerges is a sense that the artist's single most informing concern is a commitment to jewelry as theatrical statement.

Untitled Bracelet, completed in 1984, reveals almost every element of Thiewes's style, and thus will serve to illustrate the unity of her intentions. A highly abstract "charm bracelet," it maintains a thin support structure, 2¾" in diameter, wire or wirelike in relation to its coelements, playing host to a series of the most simple geometric repetitions that dangle from a small circle. Two slate disks with silver-edged center holes echo the circular bracelet support, as do various sized circles of silver and gold. Silver cones that slide along the main ring mimic the theme of circular repetition. The multiplication of an elongated. tapering tube, or spiculum, complements the basic construction. Thiewes opts to compound her design task by introducing a kinetic element, activated by either the wearer's movement or gravity. The bracelet appears to be a simple composition of geometric elements. But those simple parts are a vehicle for realizing a desire to create formally resolved work. This configuration though functional has mastered the language of modern sculpture: line, space, structure and subtle texture combine to produce a totally resolved statement. This is accomplished through her extraordinary understanding of proportion. It is always the relationship of circle to line, line to mass, mass to light that is responsible for the formal success of her work. The formal success of this piece is so complete that its "bracelethood" can be ignored. What is arrived at is pure kinetic sculpture.

The term kinetic art has been applied to everything from work that depicts movement to work that provides violent retinal stimulation. But in Thiewes's work, it describes three-dimensional form whose elements are capable of unpredictable animation. Alexander Calder, who began constructing mobiles in 1932, is perhaps the most brilliant exponent of the genre and certainly relevant to this discussion. His aerial constructions suspend abstract compositions on a filamentlike backbone, from which flow a series of wire cantilevers. The balance is engineered so that the slightest shift in air current can set the elements in motion. An elegant Thiewes earring from 1982 pays homage to the Caldervision. In her piece, a group of slender, petal-like forms are pierced and suspended from the exaggerated curve of an arched earwire. Made to dangle from a plexiglass stand when not in use, the earring echoes the grace of Calder's mobiles, in minature. But, while Calder's work is free to answer only to his esthetic intention, the sculptural jewelry of Thiewes is bound by its need to perform. In answering this need Thiewes expands the notion of kinesis to fulfill another of her own intentions, that of creating form that functions as "an extension of one's physical self."

Thiewes makes the wearer "conscious" of extended physicality, either of the body or appended jewelry form. In her work, the extension does not provide a smooth transition from Part A to Part B—or from body to structure. It creates an abrupt consciousness of self and of inhabited space. The consequence is that the wearer must constantly acknowledge not only her own body but the fact that she supports an appendage. In this case, it is a bracelet that frequently shifts its own balance and requires a corresponding reaction from the wearer. If the wearer is not responsive, the bracelet provides a prodding reminder of responsibility. In the case of the earring, the wearer must respond by wearing her hair cropped closely or pulled back from the earwire. A spontaneous move of the head could produce a painful reminder of what one has agreed to endure. The wearer must also assume responsibility for the potential in movement. The body serves not as static pedestal but as mobile armature, a dynamic and interactive element of the entire composition.

Although Thiewes's concern for movement might be placed in the tradition of theatrical jewelry represented today by Otto Künzli, Pierre Degen and Caroline Broadhead, her work doesn't look like avant-garde jewelry; it has all the classical signs of conventional jewelry. Until recently, it has been fairly small in scale, made of precious materials and essentially readable as abstract "charm" constructions. Yet, by the strength of its imposition on the wearer and the profundity of its concerns, it warrants a classification beyond jewelry. When we look at it in the context of what Rosalind Krauss calls "sculpture in the expanded field," we see the possible confluence of theater and sculpture:

"Now it is beyond question that a large number of postwar European and American sculptors became interested both in theater and in the extended experience of time which seemed part of the conventions of the stage. From this interest came some sculpture to be used as props in productions of dance or theater (Noguchi/M. Graham), some to function as surrogate performers, an some to act as the on-stage generators or scenic effects. . . . In the event that the work did not attempt to transform the whole of its ambient space into a theatrical or dramatic context, it would often internalize a sense of theatricality—by projecting, as its raison d'être, a sense of itself as an actor, as an agent of movement. In this sense, the entire range of kinetic sculpture can be seen as tied to the concept of theatricality."

The conic bracelets confirm this observation. As pure form, their graceful spiral sweeps have a hieratic, even ritualistic presence. As jewelry, they are assertively dramatic. The angle at which they flare out from the wrist creates a wide circular cage for the arm. They are antithetical to the body's contour. They force the wearer to be totally conscious of their presence and alter her movement to accommodate the form. The arm of the wearer cannot rest comfortably at its side when housed in this structure/stricture, nor can the wearer don additional clothing without first removing it. The wearer becomes a willing participant in the "stage setting," working her way around the prop in movements directed by Thiewes's jewelry. At the same time, the very drama of the jewelry places the wearer on stage.

Beginning in 1982, Thiewes extended earlier earring experiments and produced a long (5″ to 6″) structure, which supported an array of disks and cones. These are strikingly successful esthetic statements, enhanced by her fastening solution, which, in effect, becomes nonexistent. Two approaches were taken. At first, the singular wire was honed at each end to be able to pierce the supporting fabric. By slightly arching the structure, the wearer was able to provide enough tension to keep the piece suspended on its cloth field. In a later refinement, the single element gave way to a design in which the sculptural statement was essentially "split" between two halves. By drilling tiny receiving holes in certain of the sculptural elements, and providing again a subtle curve for tension, Thiewes devised a masterful way for the wearer to stab some fabric with one half of the pin and then provide closure by weaving the second stem through carefully engineered holes. A delicate twist would lock the composition into place. In a further refinement, Thiewes was able to devise some pins where the holes were so ingeniously planned that they were able to accept the male element from either end. The result was that the wearer was able to achieve two very different arrangements with a "single" pin.

With time, this format has grown steadily bolder. The delicate wire support has given way to a thick yet graceful spiculum, which is drilled to accept a circular support of form from which dangle the usual array of carefully proportioned geometry—disks of metal and slate, other circles, spicula. At 9″ long, they no longer provide discreet addenda to the outfit. Worn across the chest, they are the outfit. They are the first thing seen—they greet the viewer aggressively—they expand the wearer's presence and dramatically signal the wearer's individuality. If they are worn diagonally by a woman, they emphasize the breast at the same time that they echo it. These pieces have grown to take center stage—they are over-scaled and daggerlike in their silhouette. They stab and they grab your attention—they are riveting!

It becomes clear that the way Thiewes had attended to the body as armature for her sculpture places her work in the context of kinetic art. Krauss informs us that it is valid to also place such work in a performance milieu. What remains to be discussed from the artist's own intentions is her investigation of light. And Krauss reminds us that light-art too can be seen to fall under the umbrella term of theatricality.

Thiewes makes use of light in an unexpected way. She eschews the standard jeweler's technique for addressing light as a property of refracting stones. Instead, she has chosen the language of the sculptor—using surface quality, line and mass to make her eloquent point. Thiewes has worked to develop forms that convey a minimum of extraneous material to the viewer; they are vehicles for the subtle dynamics of matte and polished surfaces, metal-to-slate pattems and line-to-mass relationships. One small detail in the bracelet makes the point well. Two slate disks of vastly different diameters dance among the metallic circles. The larger of the two has its surface marked by the regular patterning of incised pocks. The reason is to cut down the visual density of the expanse of slate. By incising it, Thiewes makes the surface reflect more light, thus keeping the delicate balance in her composition.

The series of pieces that utilize slit and bent disks on wire supports are an exciting light-utilizing statement. The formal elements are, again, exceedingly simple. It is their use that is sophisticated. For Thiewes has created a disk whose surface and edge have been repeatedly angled and manipulated to maximize their ability to reflect light. Worn against a stark ground, they can at first deceive the viewer into thinking that there is a clear refracting stone within the composition. Only on closer inspection do we learn that the sparkling effect was created with metal alone.

As the light is captured and reflected off the planes and edges of the work, the compositions take on an additional vitality. In other words, the effect is such that the light is harnessed not only to become an element in the formal structure but an agent for the motion itself. It may be seen as intensifying the movement of the individual pans to the point that the light becomes a moving player as it ricochets off the surfaces.

Movements and sound have a mutual history in the world of performance. While obviously, sound cannot be produced without movement, the leap to a musical interpretation of Thiewes's work became apparent as our interview progressed.

Thiewes's husband is a musician, so it is not surprising that she has a voracious appetite for music and an eclectic taste. Music is a constant companion in the studio. She tells of how she might be deeply engrossed in her work, when suddenly she feels the need to make a dramatic change at the stereo. The many recordings from which she might choose at one of these moments run the gamut of the aficionado. Varese to Django Reinhardt, Coltrane to Tom Waits, The Roches to Laurie Anderson may be called upon to conjure up just the right mood for what she is trying to achieve visually. It is not surprising to find that music has actually been incorporated into her work; it may well be why movement entered her work in the first place.

In the early pieces, although sound is present, it seems almost an accidental by-product of the design process. Beginning with the single ear sculptures of 1982-83, where two vertical wires support two different compositions of silver and/or gold disks, the wearer is privy to a secret. Seemingly at random, when motion instigates, parallel clusters of disks occasionally "kiss," producing a "ting." It is high-pitched and pleasant to the ear, yet so low in decibel that it can be known only to the wearer. It happens infrequently, perhaps several times in the course of a day. But it makes the wearer pause. It serves, together with the edge of the widest disk that occasionally brushes the cheek, as a "consciousness-raising" tool. In an ironic way, it implies Thiewes's theatrical intentions as it thrusts the wearer into a performance- even if for an audience of one.

When Thiewes extended her linear, additive forms into the "dangle/bangle" structure. the sound could no longer be deemed accidental. As she added moving parts of different sizes and densities, the melodic factor grew more prominent. As their very scale and configuration dictated personal movement, they no doubt dictated where they would be worn. The prudent owner would probably take them to a parry but not to a boardroom. Thiewes forces the wearer to make contextual decisions as to where the jewelry is to perform.

I have occasionally alluded to sexual referents in Thiewes's work: the wire pins fasten when male elements enter receiving holes; the larger pins echo the breast form and call attention to it. The point is easily made that if musicality is a common thread, binding much of the artist's thought, so too is sexuality. It has been present from her earliest investigations.

For her thesis work. Thiewes created an ambitious multimedia torso form, a corset or bustier. One of the two variations was fabricated of steel, brass, ivory and leather. As an aside, it is worth noting that this early piece transformed the wearer into a performer. The piece took 40 minutes to get into, while the materials made it even more difficult to endure. It was costume rather than jewelry. But more to the point, this piece was sexually evocative. Owing its form to a woman's Victorian undergarment, its rear lacing and front metal hooks suggest all the constriction and repression symbolized by that period. The lacing, the metal and the fact that the bodice is of leather suggest the deviant sexuality that is frequently the product of such repression.

Subsequently, the sexual codes take a very different form. In fact, they are the form itself. Thiewes's geometric vocabulary, pure and pristine as it may appear to be, can be construed as male and female metaphors. Throughout her work, we find a leitmotif of the female (circle) frequently opened, often entered, regularly pierced by a male lance of varying proportions. The ubiquitous proximity of the breastlike cone only reinforces the suggestion of a sexual vocabulary.

In a pair of earrings from 1982, a gold spiculumlike form, sliced in half lengthwise, serves as the dominant motif. It appears to have speared and skewered two parallel gold disks that come to rest horizontally at the top of the pointed form. The penetration symbolism is quite pronounced at the same time that the three gold elements may be easily viewed as a stylized depiction of male genitalia.

Many of the linear, single-element pins lend themselves to sexual interpretation. In an elegant and simple example from 1984, the gold shaft enters a series of silver cones and circles. The reading may even be extended to include a statement on sexual roles. Thus the "male" is fabricated out of the more precious material. The role of the female is highly limited and proscribed by the axis set up by the male. In fact, the "females" are hardly capable of independent movement, but instead are open to manipulation.

Although Thiewes has used her geometric vocabulary to create purely sculptural forms without function. I have refrained from discussing them because I have not seen them. However, in a recent Metalsmith article (Spring 1987), Michael Dunas responds to a piece entitled Stella Bottero:

We know it is palm-sized and our memory bank acknowledges reality equivalents. When we look for objective correlatives to satisfy our inquisitiveness, we begin to feel the 'spikiness' of the pointed legs, the 'sharp' edges of the slate , the 'razored' studs that emerge from its surface. The title of the composition suggests a feminine analogy, and we begin to sense that the legs are spiked heels, that a woman's character is bottled by a well-turned physique, polished and poised. Beneath this stereotypical image, or above it, in this case, there lurks an abrasive resistance, a studded rebelliousness, a dangerous consequence to categorization. . . . As a metaphor of manipulation, it craves to be manipulated . . .

The most current work is the culmination of all the artist's explorations to date. In the case of the large, overscaled pins, Uptown Dance Series from 1985-86, the sexual implications extend beyond the symbolism already described. Worn as they are on the chest, they seem to signal a "look-but-don't-touch" message. And their spiked quality may be viewed as so menacing that they take on the power of a weapon, real or implied. It is within this context that I would like to explore the recent direction other work, which, in the final analysis, can be seen as the grand crescendo of all her diverse themes.

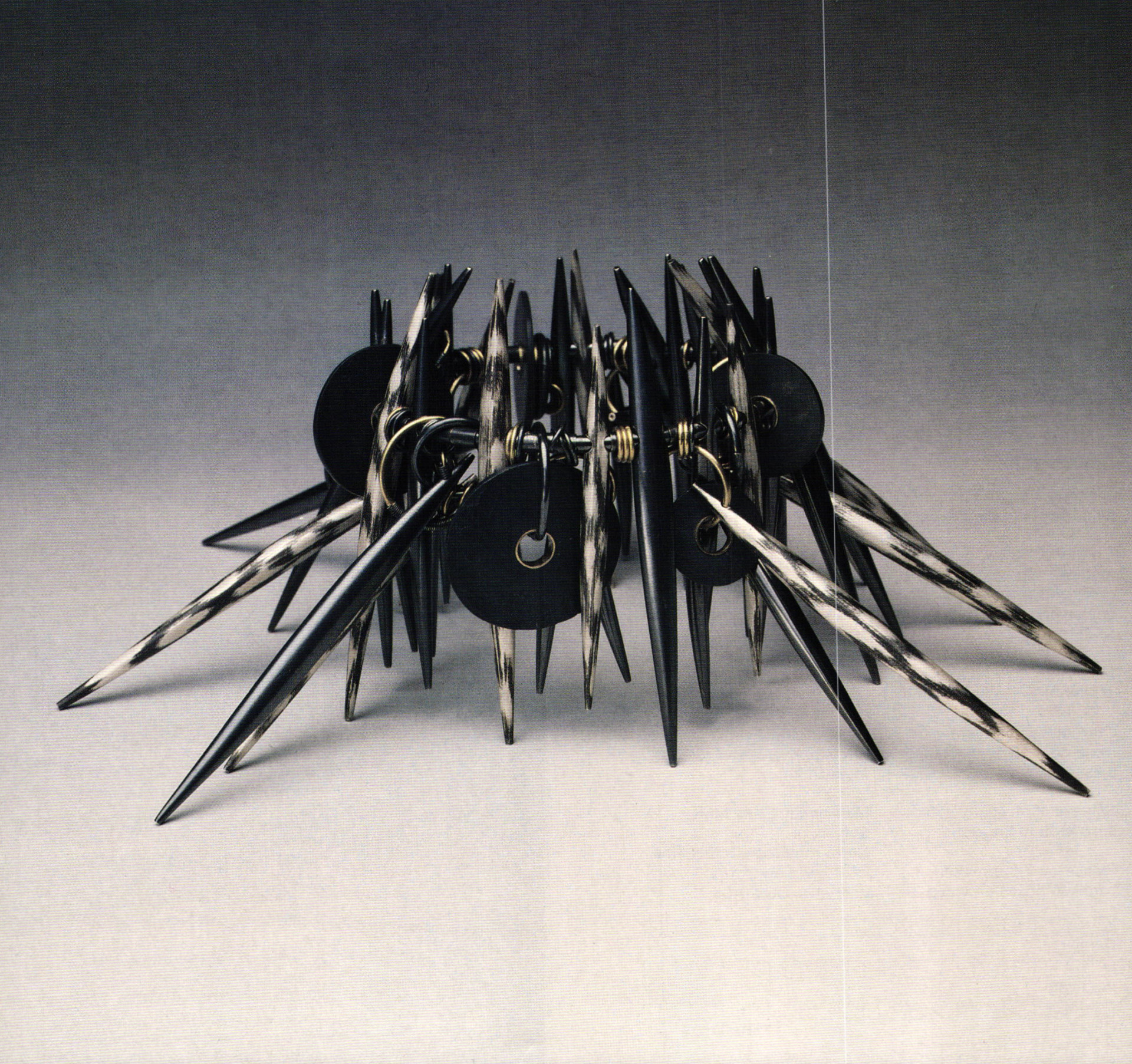

Bengal I and Bengal II from late 1986, are two extraordinarily powerful bracelets. It is all here—the constructivist acuity and compositional clarity, the highly personal vocabulary. the rhythm of form and surface, the theatricality, the musicality and especially the sexuality.

The means are the same, too, except for one new conceit, introduced in 1985, a surface treatment of mottled stripes, achieved through a process of heat and chemistry. It is a brilliant and welcome addition. This technique provides an energized surface for the spikes as well as a new and unprecedented animation for the overall composition. It is handled in such a way that it actually echoes the form of the element it enhances at the same time that it sets up a visual vibration. The result is that it becomes a retinal accompaniment to the aural range of the composition.

Thiewes says she named Bengal I and Bengal II for the stripes of the tiger, sleek stalker in the steamy jungles of India, Pakistan and Africa. Even as they point to that beautiful and sensual beast, there are numerous ways in which these pieces manage to evoke much more the mystery of unfamiliar and exotic places.

At 9½" in flat diameter, the overall form of these bracelets takes on the super scale we have previously encountered in the recent linear pins. But upon, the tiger stripes and the inevitable jungle associations, a new referent is introduced—tribal modes of body adornment. Repetition, seen clearly here in circles and tapered spikes, is a frequent factor in primitive jewelry. Once again, the very basic sexual nature of these forms cannot be denied. They remind us that the very wearing of jewelry (in more than just tribal worlds) is frequently a means of transmitting sexual messages—availability, status, prowess, accomplishment, in addition to the obvious attempt to seduce. But there is more. Raised up on the tubular tips, the artist's preferred installation, these bracelets suggest the controlled energy of an animal poised to strike. Inherent tension, indeed, impending danger are implied. Not only do they at first seem dangerous to wear, but they are dangerous for anyone who gets too close. The implications of spikes, daggers. Spears and the slate shields all allude to the weapons employed by a battling tribal people. Those battles pit man against man, against beast, against woman. And so the bracelets take us full circle, back to the universal sexual struggle; pulsing visually, pulsing sexually. These bracelets with all their physical and psychological weaponry are truly dramatic sexual statements.

At a moment when 27-year-olds can show at MoMA, and artists in their early 30s can have retrospectives at the Whitney (Eric Fischel; David Salle), the artist who concentrates on personal performance instead of publicity is a welcome find. Rachelle Thiewes's commitment to her own concerns has resulted in a coherent body of work notable for the richness of its content as well as its provocative beauty. A statement that speaks with clarity and integrity, her work transcends the contemporary appetite for self-congratulatory media coverage.

Notes

- Rosalind E. Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture (New York: Viking, 1977), p. 204

- Ibid.

- Michael Dunas, "The Modern Ache: Form Beyond Function," Metalsmith (Spring 87), p. 22

Vanessa S. Lynn is the director of the Gallery at Workbench and a frequent contributor to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.