Intimate Parallels

9 Minute Read

Both in art and in literature, the function of the frame is fundamental.

It is the frame that marks the boundary between the picture and what is outside.

It allows the picture to exist, isolating it from the rest; but at the same time, it recalls - and somehow stands for - everything that remains out of the picture.

I might venture a definition: we consider poetic a production in which each individual experience acquires prominence through its detachment from the general continuum, while it retains a kind of glint of that unlimited vastness.

Italo Calvino

Notes, Under the Jaguar Sun

The consideration of the relationship between objects and their surrounding space is essential in terms of installation art. As Calvino suggests, a line between the two entities is a significant realm, and, in an age of Electronic media, when edge conditions of time and space are being transformed and perceived in a new way, the study of these boundaries is necessary. Installation art introduces some curious questions about edge, considering the permanent, static, regulated, and finite context of the gallery condition. Not only the transient status of the work presented, but other circumstances of the setting, for example the typically public nature of the gallery context, create the challenge of connecting the audience on a level which is lasting, familiar, intimate, and ultimately, real rather than staged. One product of the installation artist may ultimately be the creation of recollections about an idea and its short but genuine existence. Installation art itself transforms our notions of the space by way of additive and subtractive constructions and, if the illusion or vision is strong, the memory of this state haunts that space when it is revisited even after the manipulation has been reversed. The environmental scope of installation art can dramatically affect the spectator by changing the space of its constituent elements in relation to the viewer of the work. The relation of the installation work to the human body introduces notions of other relationships between art and the body. The intention of this article is to consider the potential parallel function between installation art and wearable art, by way of transformation of the space, blurring the edges of the work, maintaining a quality of transience, and connecting in an intimate way to the space and the audience.

If we consider the presentation space of the installation to be the gallery then the parallel space for wearable sculpture would be the landscape of the body. Even if the gallery space has been architecturally neutralized so as not to effect the choreography of the work, the general spatial configuration of the interior will vary if only slightly, from place to place. All galleries are not identical white boxes. The archetypes from which each space is comprised are particular and hold meanings which set the base for the environment with which the installation will react. Therefore, the potential edge conditions for the piece, at least initially, are somewhat established. More importantly, geographic location and sociopolitical function of the exhibiting space render the blank space innately charged. The phenomenology of the piece, which is potentially contextual, therefore, will change if transplanted from place to place. Similarly, the landscape of each body adorned with a wearable piece varies from person to person. Each character contains a history which potentially reacts and impacts the reading of the piece that is worn. Furthermore, the locations to which this animate pedestal piece will travel and the audience to which it will be exposed is so varied that the piece will inevitably mean different things depending on the environment in which it is introduced.

What is a given here is that, in both scenarios, the work has a certain frame within which it can be developed and a space into which it can fit. In the case of the gallery the construction includes various archetypes, including the door, the wall, the corridor, etceteras. In the case of the body the elements include the finger, the neck, the back, the chest. So when the reinforcement or refection of these elements begin to include the larger place into its formal state' the reading of the edges between the piece and the pedestal ultimately begin to mesh. Although the immediate place into which the two works nestled themselves would seem to vary greatly - the gallery space being a void and the body, a mass - there is a social space, surrounding the body, in which the wearable work actually operates, and which resembles that of the gallery. The transformation of the meaning of these entities by the work is somewhat similar.

In Ann Hamilton's aleph, an installation at MIT's List Visual Arts Center, for example, the configuration of the wall-mounted books covers and seems to replace the existing wall of the space, from floor to ceiling. The books become an architectural element, and this edge, which would ordinarily separate the space of the room from that of the piece, is blurred; the viewer enters the piece because the viewer has entered the room itself. The architecture of the gallery becomes that of the piece. The artist then uses the environmental scale of the/her frame to force the movement of thought to the details and actions of other elements in the piece: a small desk at the far end of the space where a person sits erasing the reflections from a stack of book-page sized mirrors. An opposing wall becomes a projection surface for a magnified image of a moving mouth filled with marbles and thus unable to speak. The transformation of the walls is essential in leading the reader to surmise a narrative of reflections and obscurations; it allows them to enter the space that has become possessed. And the transformative aspects of an installation such as this changes the function of the exhibition site from a neutral container to an expectant space waiting to be filled. The sterile white cube is invited to become involved.

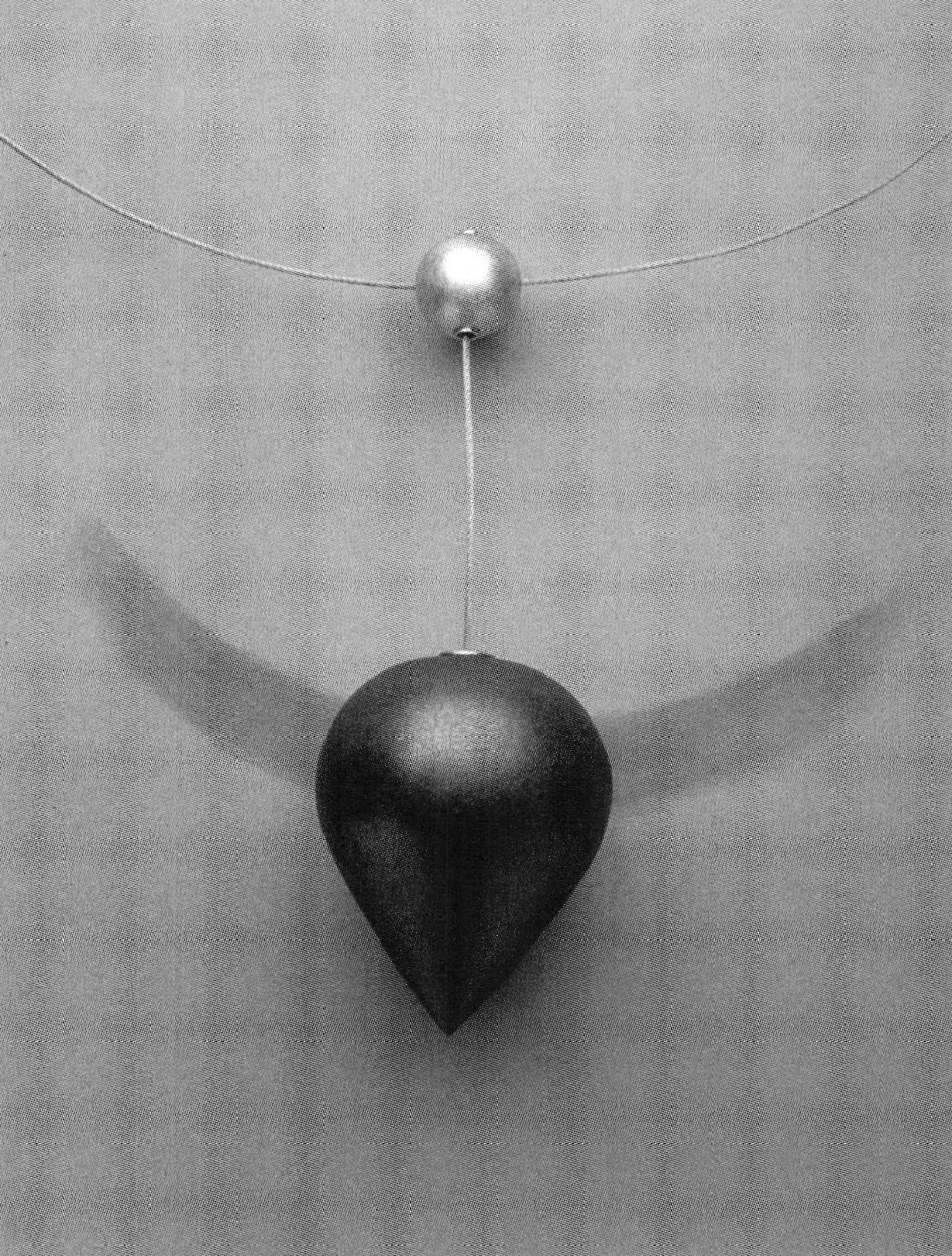

An example in the realm of the wearable object, is the work of Joan Parcher. Her set of pendulum pendant pieces exhibit contextual ideas. Shown as wall pieces when not worn, her heavy pendants hang from simple and slight metal yokes. The pendants themselves are not metal but sensual and simple primary forms cawed from graphite and designed to fit the proportions of the hand. The material renders black streaks on the wall marking the movement of the pendulum. This effect is heightened when the pieces are worn, because the movements of the wearers activate the pieces so that the graphite distinctly marks the skin and the clothes. The chest becomes the site where the boundary between the piece and the pedestal are blurred. The wearer is invited to become the artwork.

Another artist of wearable works, Ela Bauer, makes neckpieces from latex. Her form-fitting collars suggest a second membrane, mimicking the neck in a way similar to which Ann Hamilton's books reiterate the wall against which they are mounted. The color qualities of the latex material further bleed the visual difference between it and the skin it embraces so that the elements embedded in the collar become extensions of the edge of the body.

The Hamilton and Parcher pieces involve an issue of time as well. Indeed, the act of the set-up and tear-down of the installation piece defines its ephemerality and distinguishes it from other art objects. The labor expended in the transitional moments of the installation follow a protocol comparable to dressing and undressing in the context of the wearable. But, in the cases of the Hamilton and Parcher pieces, an issue of time is designed specifically into the details of the work. In the Hamilton piece, the human presence sits continually erasing the reflective surfaces from the book of mirrors. The stack of cleaned glass pieces to one side of the work area indicates the progress in the process of this compulsive act. The Joan Parcher pieces continually disintegrate as the graphite is abraded by the surfaces of the clothing. This reshaping of the piece challenges traditional notions of the permanence of jewelry. Temporality in both works is defined by cause and effect relationships.

In both wearable art and installation art, a sense of intimacy between the viewer or wearer and the work can be achieved by addressing the human body. This requirement is usually manifested in one way or another in wearable sculpture, but it can be clarified by consideration of certain nuances in the construction of the piece. The sense of touch is usually the criteria for these definitions. Weight, for example, is a raw material which makes the presence of the piece felt and understood by the wearer. Contact with intimate places of the body, and incorporation of sensual materials, and these points of physical contact; graphite, latex, steel, have varied affects on the skin. Proportions of elements help to achieve this intimate effect by addressing human sensory capabilities; small details to be scrutinized by the eyes, devices to be manipulated by the fingers, drapes to wrap or bind, combs to travel through the hair. The work becomes an outward extension of the body, as well as additive detail to the reading of the mass. The installation work can achieve similar results. In Ann Hamilton's work, the introduction of the human presence subverts our perceptions of the space. The living breathing entity may not address the spectator directly, but the atmosphere is changed by his/her presence. The spectator also identifies with the gestural activities of the figure, rubbing the reflections from the mirrors. Without touching, the viewer nevertheless understands, not only the potential physical qualities of the action, but begins to focus on the motivations of the gestures. A heavy silence pervades the installation. The video image of a mouth unable to speak because it is filled with marbles, is a reiteration of the interrupted reflectiveness of those erased mirrors.

There is a potential parallel between the intimate fullness of this installation and the intimate recognition solicited in wearable sculpture, and this parallel arises from an understanding of placement, of a sense that a piece was designed to fit a certain landscape, whether large or small, animate or not. The symbiotic relationship of the work to the place allows us to travel through corridors which introduce the edges in a familiar way and potentially links it to a reality which we understand. By transforming spaces, blurring edges, encapsulating poignant ephemeral notions, and by reacting to us in intimate ways the resulting memory of a piece in either grouping can be lasting and highly influential.

Cynthia Pachikara has a background in architecture and is currently pursuing a second Master's degree in Fine Art at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.