The Jewelry Art of Lisa Gralnick

11 Minute Read

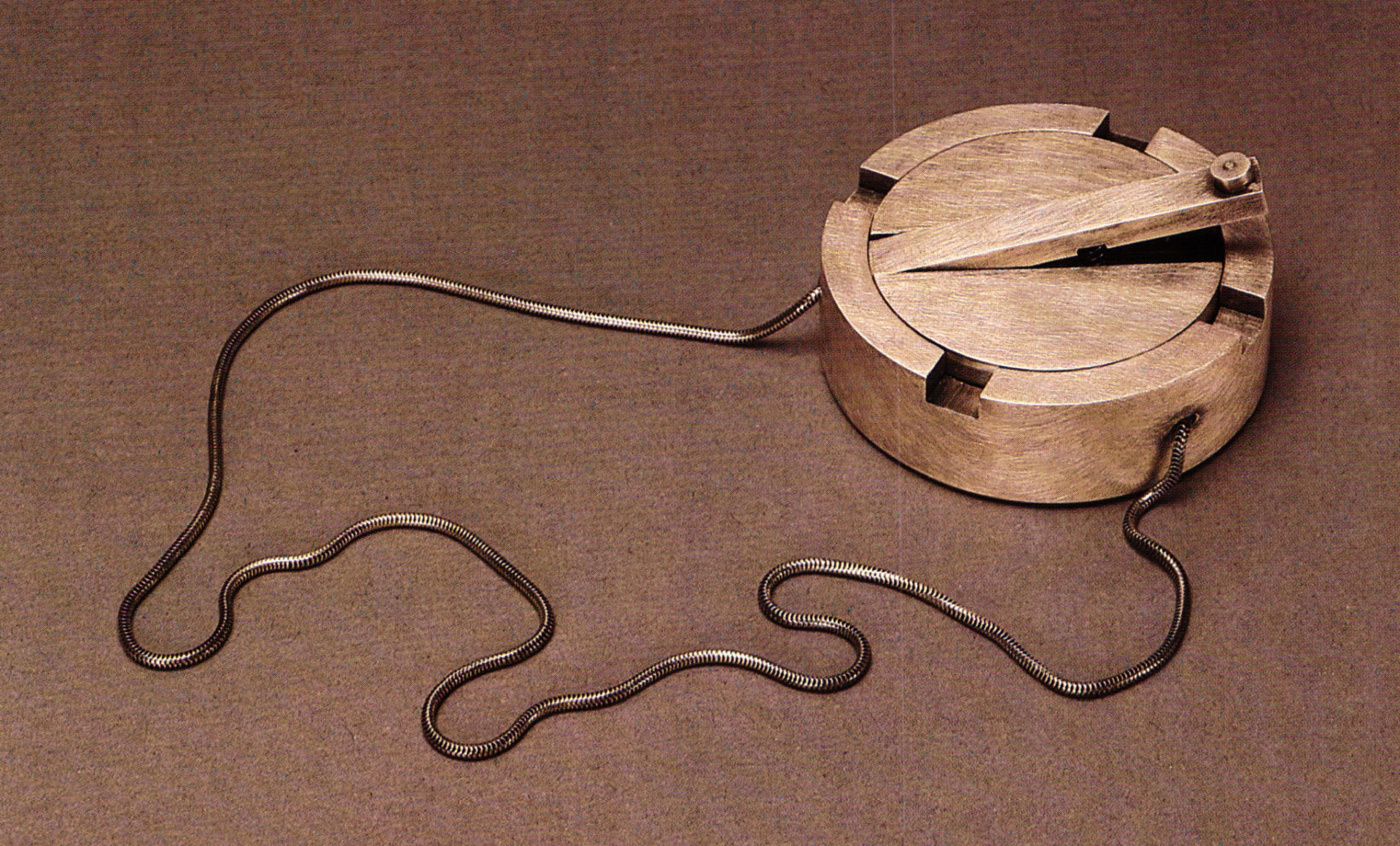

Lisa Gralnick makes jewelry of rare power from imagined artifacts of our own time. Its extraordinary impact derives from her sure compositional eye and her success in focusing our attention on forms which, in an important sense, epitomize how we live - forms we've often seen but rarely noted, forms embedded in our subconscious. She shows us fragments, simplified and ordered, which call to mind bits of machinery, space objects, structural elements - or perhaps a gyroscope, a surveyor's plumb line, a camera rewind crank. As she transforms them, they become objects of beauty, objects to contemplate as well as to wear.

Creativity and logic join together in Gralnick and emerge in her work. Math was her strongest subject in high school. She says she took after her father, a dentist with a head for logic and a professional concern for precision. But her real interests lay elsewhere: in drawing, playing the violin, and "making things." It was at a community center jewelry course that she discovered metal. "In the actual processes of metalsmithing," she says, "I found the perfect merger - a medium that demanded very precise, logical kinds of skills and thinking and at the same time provided a creative outlet."

For her undergraduate work, Gralnick chose Kent State University because it had a strong metals program and because she admired the work of Mary Ann Scherr, which combined both science and art. She took the usual array of classes in fine art and the crafts, but at the same time she enrolled in Kent's Honors College and plunged into courses in literature and physics. She avidly read the great writers, from Proust to Dostoevsky to Thomas Mann. Literature became a principal source of inspiration; literary references infused her jewelry. In the art department, Mel Someroski taught her to love enamel and took a great interest in her reading. "He was everything a teacher should be," she says, "and the first real artist I had exposure to."

Gralnick earned her BFA from Kent State in 1977, then we fit to graduate school at SUNY/New Paltz. There, she recalls, "my metals education really began." She studied with two teachers who were polar opposites but for her were the perfect complement. Kurt Matzdorf, renowned for his hollowware and commemorative pieces, insisted on a rigorous, classical training in the traditional arts of silversmithing, Robert Ebendorf, the contemporary man and innovative artist, taught his students to follow their muse. Matzdorf urged his students to work figuratively, drawing imagery from nature. Ebendorf supported Gralnick's search for "an abstract language which had nothing to do with literal references." She acknowledges the influence of both teachers in the development of her own work, which eventually came to combine both referential and abstract elements.

At New Paltz, Gralnick began to explore a subject which had fascinated her for years: the ways in which objects of art have functioned in the cultures which have produced them. As a child visiting New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art with her parents, she had always headed first for the room with the African masks and fetishes. Later she began to wonder how these ritual art objects were able to bypass her logical, intellectual self and appeal so strongly at a "gut level," as she puts it. She thought about the mediating role art played in these indigenous societies - how people chose art objects in their effort to control or placate the unseen forces and spirits which they believed determined their destinies. In her jewelry Gralnick began to draw on forms and ideas derived from these magic-bearing artifacts of "primitive" cultures, using precious metals with enamel for color.

After receiving her MFA in 1980, Gralnick spent a year teaching enameling at Kent State and a year as head of the jewelry department at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax. By 1983, during her stay in Canada, she had become dissatisfied with her jewelry. The objects from which she derived her ideas performed a valid function in the societies in which they were created, mediating between people and the occult world around them, but Gralnick had come to realize that if her pieces were to "function in the same way in our own society, I had to search for forms more relevant to my own time." The way in which she ultimately resolved her search could hardly have been more unexpected.

Some months before her departure for Halifax, while driving along a country road in upstate New York, Gralnick had stumbled quite by chance upon a structure which was truly bizarre a house whose almost windowless exterior was made entirely of black rubber. It appeared to her dark, ominous yet compelling, and she found herself returning to visit it again and again. In Nova Scotia she encountered a similarly unsettling object: the black hulk of an abandoned submarine, rusting behind a barbed wire fence in the Halifax harbor. She remembers going to the harbor often late at night to stare at its "huge, black, threatening, inaccessible-looking form."

Gralnick's mood during this period was increasingly troubled, her view of the world increasingly dark, and these two images seemed somehow to relate to her. Back in New Paltz, they continued to haunt her studio, but she could not find a way to deal with them in her art. Then one evening as she sat listening to a Wagner recording on her stereo, something came loose from the wall and landed on the record, shattering it to bits. Startled at first, Gralnick studied the fragments and then, almost without realizing what she was up to, began to assemble them with glue and build a house. For weeks this strange object made of record shards lay on her bench and kept demanding her attention, until one day, quite without premeditation, she stopped her work and began clearing her studio of all her precious raw materials. The following day she bought a supply of black acrylic sheet and began to teach herself how to work it.

Such was the origin of the black acrylic jewelry which was the subject of her first major solo exhibitions: at VO Galerie in Washington, DC (1987), Galerie RA in Amsterdam (1988), and CDK Gallery in New York City (1989). This new work was the very antithesis of what had preceded it. Instead of gold, silver and enamel, the sumptuous traditional materials of jewelry, she now worked in that quintessentially cheap contemporary substance - plastic. Instead of delicate, elaborate structures, her new forms were bulky and stark. She rejected color in favor of nonreflective black matte surfaces, which focused attention solely on the form without distraction. The forms themselves were gloomily threatening: houses without doors, tombstone shapes, and shapes suggesting missiles and submarines. Each had a tiny opening of glass, a window into some mysterious, inaccessible interior space, to be filled, perhaps, by the viewer's darkest imaginings. Gralnick describes these pieces as "at once intimidating and uplifting;" she called them her "Rubber Houses."

In time the pieces she was making began to be less ominous. They now referred to objects from everyday life - gears, switches, oven dials, car parts - things we use to exert control over our lives. They were, in fact, contemporary analogs of the ritual objects of "primitive" cultures which had inspired Gralnick's earlier work, the work abandoned as unsuited to our own society. Gralnick's hope was that by taking contemporary objects, turning them into abstract compositions, and putting them close to the body, these forms would resonate subliminally and communicate to the subconscious. Though they were large, they were lightweight and eminently wearable. Their exquisite craftsmanship and soft-seeming surfaces made them precious and desirable.

Three years ago Gralnick's work took another dramatic turn, not because she thought she had exhausted the possibilities of black acrylic, but because she found that she missed the feel of working with metal. She was curious to discover what she would make in gold after five years of working with plastic. With some fellowship money from the NEA and the New York Foundation for the Arts, advances from a few other collectors, and her own savings, she splurged on $15,000 worth of 18k gold. She set out to work the gold with the same attitude she had used in approaching the acrylic, and the result was a series of brooches which again suggested fragments from industry and space. They are simple in composition but exquisite in detail. The craftsmanship is so impeccable as to seem effortless; one senses that if these objects were enlarged to industrial scale, there would still be no visible imperfection. With these brooches, Gralnick succeeded in giving gold an industrial look, as previously she had lent preciousness to plastic.

In the gold brooches, as in the black ones which preceded them, Gralnick had expressed her continuing fascination with things mechanical. She has always found beauty in the forms of simple devices, in the way they follow nature's laws and in the way they enable us to use those laws to fill our needs. The latest development in her constantly evolving work was shown at her most recent one-person exhibit, at Jewelerswerk Galerie in Washington, DC, last fall.

Her newest pieces are pendants and neckpieces which explore the visual potential of simple mechanisms - spools, pulleys and cranks. The Anti-Gravity Neckpieces, for example, have small spheres or cylinders suspended from them which can be raised or lowered mechanically, enabling the wearer to choose the length at which they will be worn, from waist to knee. The forms are without adornment, stripped to their essence; every visual element has a mechanical function. They are mostly of silver, but like the black acrylics, their surfaces are finished in such a way that no refection distracts attention from the forms themselves. Gralnick's goal is to bring the wearer into an intimate relationship with some of the essential mechanisms around us, and to force both wearer and viewer to observe for the first time the beauty which resides in their forms and in their functioning.

Gralnick's jewelry has found a growing clientele, who buy her work at the craft shows where she still exhibits, from galleries here and in Europe and from her studio near New Paltz. After several years of teaching at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, she was recently appointed coordinator of the metals department at the Parsons School of Design, a position which now absorbs a large share of her time and energy. Although the job has left her less time to work, it has also lessened the pressure to produce, and at the present she finds this welcome. Her thinking is once again in transition, and she relishes a period of pondering and experimenting at her bench.

She has only an inkling of where this might take her, but the chances are that something will develop out of her long fascination with the natural order which surrounds us. Over the years she has read books and taken courses in theoretical physics and cosmology, courses which invite speculation about the physical universe, its origins and laws. She studies drawings of early scientific instruments, and she derives pleasure, both visual and visceral, from understanding how they work. She sees theoretical physics as the link between science and art: both, she says, are "concerned with the nature of things."

So at her bench these days, Gralnick makes crude models of scientific experiments and instruments. Her current favorite is a model of the expanding universe, constructed of rubber bands and paper clips. She tries to reduce complex concepts to simple devices which illustrate nature's workings. She wants to make things which will convey to others her own sense of wonder at "how things work."

Gralnick has been asked why she bothers with jewelry, why she doesn't make sculpture apart from the body. Her response is, typically, firm and considered. She is committed to jewelry, she says, and to the centuries-old goldsmithing tradition. She sees her work as a continuation of that tradition - its rigorous demands, its "precise and respectful approach to working with materials," its dedicated pursuit of lasting aesthetic value, and the ideal that preciousness should inhere in the object itself, not in what it's made of. She firmly rejects the notion often implied in the question, the notion that jewelry is somehow a lesser art than sculpture. If she makes objects not intended to be worn - as she has done and may well do again - she wants them judged by the same standards as her jewelry. And she wants her jewelry viewed with the same seriousness as her sculpture.

Whether on or off the body, Gralnick's work seeks to connect the universe without and the universe within. She says, "It is that connection that I'm still looking for in my work and that threads through all the different stylistic changes that I've made." Her jewelry combines - and miraculously resolves - an appeal to both logic and intuition, science and aesthetics, intellect and emotion. Therein lies its unique power.

Roger Kuhn makes jewelry and occasionally writes on craft from his home in Bethesda, MD.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.