John Prip/Jack Prip: Arrangements of Changeable Form

16 Minute Read

This past year, we were treated to a major retrospective of the work of John Prip in an exhibition that originated at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence, RI and traveled to the American Craft Museum in New York.

This exhibit provided a rare opportunity to almost tangibly participate in the whole career of a living artist—a pioneer in the field of metalsmithing, who helped spur on a whole new esthetic in American holloware—an influential, if eccentric, teacher and a lover of the serendipitous.

| Mail Art: Christmas Tray and Squeezably Soft which Jack Prip sent to Louis Mueller in the 1970s |

The often inadequate confines of two-dimensionality are sorely felt in trying to recreate the overwhelming vivacity and inventiveness of Prip's work and the exhibit assembled by his own hand. So, here we offer as best as possible, a glimpse into that dynamic work, accompanied by comments of individuals who have known Prip well, many of whom have studied with him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

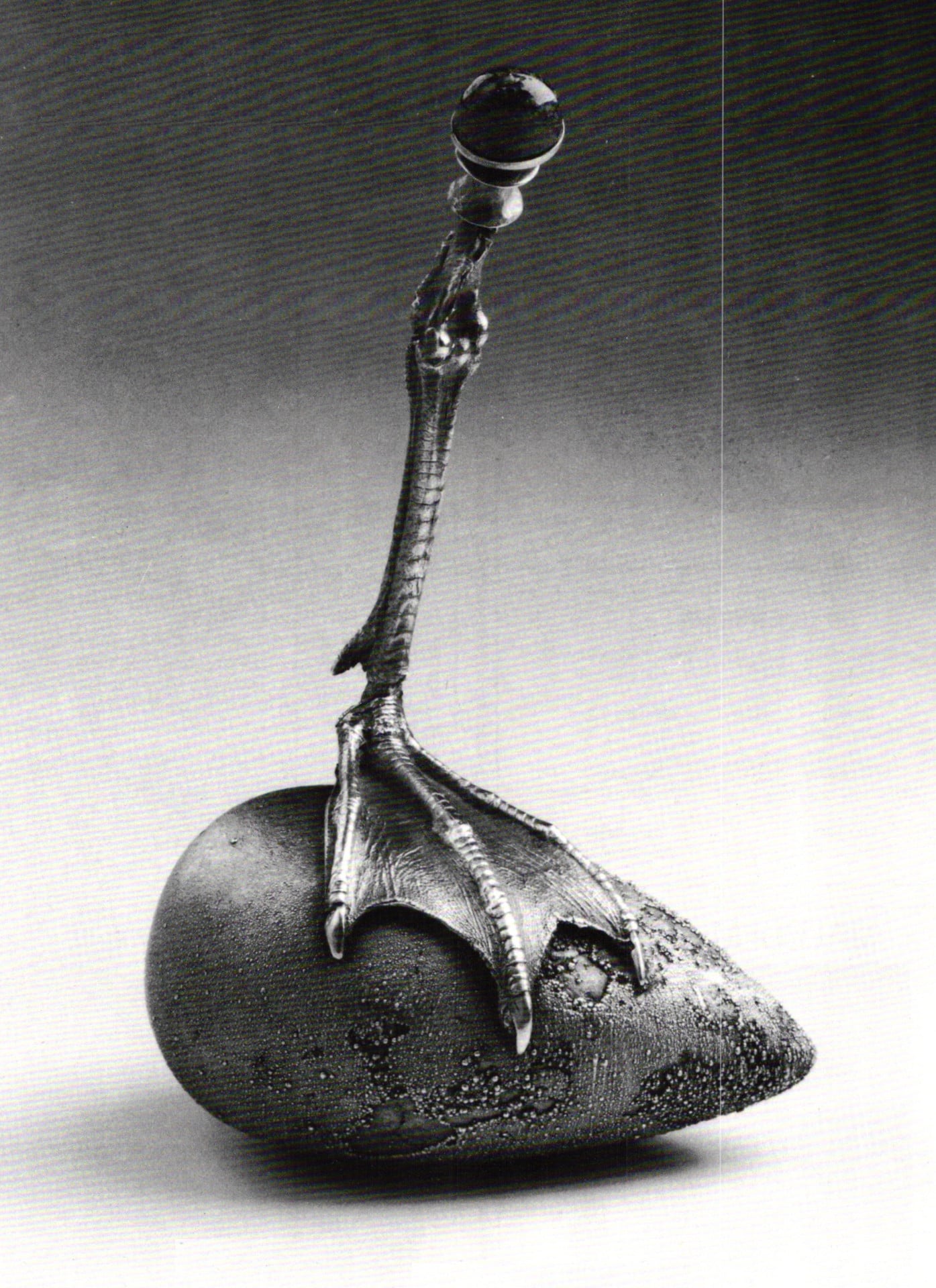

How many times have we picked up a beach stone and marveled over its shape and texture? Feeling some mysterious energy, we carry it a while in the palm of your hand. Jack Prip, or John Prip, goes to a special beach in Maine to collect these stones. Not only seeking their innate fascination, he desires them for their potential in creative transformation.

With sandblasting, some stones become highly polished. Others, polished on the exterior, have unpolished, rough cavities covered with silver lids. The lids appear as hard, decorative skins that seem to need to be peeled off. Attracted by the color, shape and texture of these stones, Prip adds personality to what nature has already provided.

Jack's work focuses on the container, which he explains is "a term that didn't exist until recently, except to describe a shape for holding something specific like coffee or cigars. Now, anything that has a hole in it can be called a container. It has a freer association." As Jack talk about his work, he becomes animated and specific. Commenting on the inspiration for a certain teapot, he remembers having "a fondness for chubby forms. I wanted to draw the spout out of the piece."

For another vessel, his intent was to make a smooth form. "I became interested in bald shapes that would sit and do nothing. I would drop the lid in and finish it off with the pot, making a seamless conformity of lid to vessel." With his own organic vocabulary, Jack invents ways into his materials and out again, never needing to sit at the drawing board and design around each piece.

Jack can take a geometric or organic shape and, with his understanding of form and careful handling of materials, give it information and purpose. There is something obdurate about his choice of materials; yet, he has the ability to soften the hard and warm the cold. A silver box with a crude, jagged texture, which Jack calls "exaggerated granulation" has two amethysts set into the lid, creating a visual relief on his rugged mesa of space. Reflective of material concepts, his containers and boxes are portraits of thought and suggestion. The sketch in the mind a certain eager possibility, while calmly harmonizing the dichotomies of shiny/dull, soft/hard and interior/exterior.

Jack's early influences, besides his rigorous training in Danish silversmithing, were also Scandinavian art nouveau and the work of Picasso, Brancusi, Klee and Miro. At age 26, when he was invited to teach at the School for American Craftsmen in Alfred, New York, he launched into the most intense, exciting time of his career.

Unlike Copenhagen where silversmithing was a trade like that of a stonemason or plumber, the School for American Craftsmen offered silversmithing and metalsmithing as something with artistic potential. With only technical training, Jack responded quickly to the concepts of potter and fellow teacher Frans Wildenhain, who had studied at the Bauhaus. Suddenly, he was exposed to silversmithing as an artist and not as a tradesman. Some of his fondest memories are of this time in Rochester—where the School for American Craftsmen moved a few years after he was hired—where he spent 20 years working, struggling and forming close bonds with other craftsmen and students.

Later Jack would work at Reed and Barton. It was here that he discovered electroforming and how to use pewter as an alternative to sterling silver. Roger Hallwell of Reed and Barton describes Jack's position, as designer/craftsman in residence: "There were no restrictions or demands imposed on him. He was simply to create by hand whatever and whenever the spirit moved him." In this distinguished position, Jack created opportunities for other craftsmen to bring creativity and design into the world of mass production.

Suffering, at times, from the difficulties of working with metal, Jack explored lead, paper and Styrofoam. "I'm attracted to these kinds of materials because much of what I do is dictated by the desire to free myself from the confines and restrictions that silversmithing imposes. It is a careful and exacting skill. Everything has to be planned out, considered. The process is very time-consuming." In the childhood memories of cutting out paper ornaments at Christmas-time, Jack found he could use paper again as a way of sketching out three-dimensional forms.

By folding, unfolding, making intricate cuts and popping out areas, he could improvise and invent quickly. Several maquettes for bracelets, metal sculptures and containers were made in paper. He also liked "the way light played on the whiteness of the paper, radiating a soft, subtle, texture and glow." This process also led to seaming and interlocking of forms in metal characteristic of his work in the mid-1970s that employed layered, nautilus-shaped surfaces of a paperlike thinness.

The saga of one such series of large cardboard units is related by Jack: "They were hard/soft, male/female units that I was very fond of. I never really felt I discovered how to use them properly. I made several large ones out of aluminum and just let them out by the pond and grass where they could roll around. The wind would pick them up sometimes. They looked like artifacts that should serve some purpose, but they didn't. Sometimes in the winter they would blow over on the pond, and in the spring, when the ice melted, they would sink slowly to the bottom."

John Prip's work was most recently shown at the Gimpel & Weitzenhoffer Gallery in New York.

- Madeleine Vanderpool is a writer living in Providence, RI.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I arrived at RISD from SAC with a big head, and what I liked about Jack was that he recognized this and he said, "lf you're confident, you don't have to wear it on your collar." Jack helped me learn about humility and what confidence really is. He introduced me to the idea of being playful with what you do, much the opposite of the way I had interacted with Hans Christensen at SAC. Jack was not as interested in the teacher-student relationship as he was about my life.

One of the most important things I learned from Jack had to do with concept and final execution. He made me see that you didn't have to consider the drawing you made to be the final idea about an object. You could change the verticals and horizontals and the object would come our much different than the original drawing, and that was good.

Oddly, Jack's recent retrospective gave me a chance to view him anew. I saw his strong will more openly. His air of confidence was only tinged with a laid-back attitude. I was most drawn to his work of the 1960s. These are the epitome of what craft should be. Later, as they became more whimsical, they moved away from craft for me. Since I never could compete with Jack's skill at execution, he could continue to be my role model. With Hans, everything was in the execution—the more perfect, the more complex, the better. Jack's work had a high quality of execution but with thought behind it and a sense of design that he adopted outside of his training in Denmark. I saw him for that reason as being human.

Jack had a habit of coming into school with apples. When I left RISD for California, I began to send cards to him along the theme of apples. Soon my whole class was sending him apple-related cards. In the early 70s, someone once sent a 36 pound squash with the address written directly on it. I must leave a box full of cards that I received back from Jack.

- Louis Mueller

Head, Light Metals, RISD

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My overall impression of being a student of Jack Prip was that it was an ongoing mental process. This came both from Jack's indirect way of interacting with his students and also from his own propensity to play visual games. Jack had a knack for taking things that serrendipitously came to him at the studio or in his office and arranging them in new and unexpected configurations. For example, one time an orange sat on his shelf for a long time and became dried and shriveled. Totally unrelated, I brought in a box of gold dot stickums. The next thing I knew there was a dotted line leading into his office up to the orange on the shelf and the orange itself was respotted gold, an action that totally changed and enhanced its appearance Jack had this ability to seize the moment, to improvise on his surroundings to the delight of everyone in the studio.

What was difficult for me, when I was a student at RISD from 1974-76, was that the learning environment was entirely unstructured. This was a sign of the times, and yet also was a product of Jack fighting his own traditional silversmithing training, which had been extremely rigid and controlled. But Jack insured that you would be self-motivated not through the articulation of some principles or teaching methods but through other, more subtle ways. We were not made to work, we were made to want to work. He was in the habit of visiting students' benches after hours and tinkering with pieces or rearranging things for emphasis. I know he was greatly involved in the students' work, because I would catch him coming by and pondering, not speaking but showing approval or disapproval through mannerisms, a sigh, a nod, even a snub, on occasion, would clearly show that he was disappointed.

A second major impact of Jack's teaching was his willingness to share his studio at home with his students. Again, this was done in a seemingly offhand manner, by, for example, the annual ritual of the Fall Walk, when we all would be invited our to the house to walk in the woods. Karen, Jack's wife, would make a wonderful meal and then there would be dancing. But the studio was always a draw and the arrangements of his own work, his tools and his collections of paraphernalia always had some meaning for me. And I learned that no matter how, casual-looking a detail of any piece that he had worked it over very carefully and intentionally.

Another important influence that Jack had on me was his urging me forward to do smithing, even though I was reluctant to begin on something unknown. I was most interested in jewelry, which he felt he didn't have a touch for, even though he has made some that I very much admire. He did feel that a jeweler had a different sensibility from a smith. Nevertheless, raising taught us how to achieve form in metal that was important for a jeweler. It takes jewelry away from a constructed attitude and gives it volume and form. And Jack was concerned that jewelers not just make things out of sheet metal and wire. The application of silversmithing techniques to jewelry also allowed people to get involved in small projects that were not as daunting or time consuming as a teapot or other traditional smithing projects.

- Robin Quigley

Assistant Professor, Light Metals, RISD

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There are only a handful of true artists in the metals field and even fewer who teach. Those that can spark a student's unique individuality and creativity without imposing too much of themselves are even rarer. Jack Prip leads the pack.

Jack taught through broad concepts and ideas; his assignments asked you to ask yourself questions, led you further along your own path and were always without preconceived expectations. Each student arrived at a totally different result based on his or her own interests.

Our first assignment in graduate school was to consider how nonmetal things looked and were put together and to make something in metal inspired from this consideration. This way of looking at things has never left me, in fact, I'm still making "pillows."

Jack couldn't seem to resist rearranging things on our benches; we'd arrive to see our latest work in progress upside down, juxtaposed to what, at first glance, appeared to be the most unlikely thing. But it never failed to jog our minds and open up yet another door.

The assignment to work with a company in Providence and include an industrial process in our work seemed like an insurmountable task at the time. First, we had to scour the phone book for companies (a revelation), learn how to appear convincing on the telephone—enough to get through to someone in the actual plant—to even find out what they actually did (tough but got easier). Then we had to get there, tailor the assignment to the process and still come up with our original idea. Well, we really grumbled about that one, but had we not done all that we would never have begun preparing for all the opportunities it began to unfold, thanks to Jack!

His approach was always: don't analyze it, just do it, and if there's someone our there who can do it better, have them do it for you. We came to refer to it as the "no hassle, heat & beat" approach, attempting to concern yourself with where you are going more than how you get there.

I'm glad I had an opportunity to work with Jack and to be part of the metalsmiths he influenced in his reassuring way.

- Jan Yager

Independent Jeweler, Philadelphia, PA

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When I was an undergraduate at Philadelphia College of Art in the late 60s. Olaf Skoogfors regularly showed slides of his friend Jack Prip's work. Right from the first, I was entranced. I came to RISD graduate school in woodworking in 1971. At the end of the first semester, I transferred to metals to study with Jack. His reaching method was to throw me off balance as frequently as possible, I'd show him a piece, feeling pleased with myself. He'd pop that balloon in a hurry with a calculated remark. I would have no choice but to think about the piece in a much more meticulous way. This unsettling method prevented me from falling into a complacent groove with the work, but rather made me go forward. You can't ask for much more than that.

- Jonathan Bonner

Independent metalsmith sculptor, Providence, RI

The following are excerpts from comments made by current RISD students after visiting Jack Prip's show at the RISD Museum.

Prip's vessels represent to me his unearthly ability to manipulate materials; rigidity does not hinder Prip, rather it inspires him. However, it is Prip's "art objects" that I enjoy the most. They combine his mastery of material with whimsical experimentation. In a way, John Prip is a Surrealist in that he does not readily know the intent of his pieces, neither does he expect the viewer to be infused with meanings. Prip's pieces are born from his wandering imagination and demand imaginative, emotional response from the viewer. To be shocked by the mystery of his "objets d'art" is a worthy reaction that need go no further. A dead fish cast in pewter, bisected by a cube that has on its face a half-sphere and a little squiggly mark is bizarre, perhaps arbitrary; yet, the mystery it evokes is wonderful.

- Alessandro Zezza

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

One of the remarkable things about Prip's work is that although it is essentially serious, it also has wit. There is a lightness to it, and the viewer finds pleasure in seeing Prip rise to each new challenge and master it. The stones I liked because of their simplicity of shape. Prip took nature and worked on it, almost the way nature would by preserving the shapes of the stones, and at the same time enhancing these shapes. In some stones he hollowed out a space and filled it with beach pebbles. In others he worked on the surface in such a subtle way that his surface seemed to belong to the surface of the stone. He also hollowed out the stones and then closed them again with silver lids. The stones never ceased to be stones, but Prip increased their beauty by giving them a unique energy. It is this energy that lives in my mind after the show.

- Marissa Brown

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was impressed by Prip's ability to include the structures of other materials in his work. Bending sheet metal to mimic the natural rend of paper creates the impression that, like paper, the metal is resilient and fragile; like it would snap back if released, and to push it any further would destroy its form. Metal stretched into long shell-like stalks has a natural weightless quality. A bone's curve is added to a flatware design. Drips of water fall out into space. We know that it is metal, the color is left exposed, yet it takes on an additional structure and reveals ability….

Retrospectives are good in that they reveal a progression of work—improvement, exploration, learning. Prip's work shows all of these, along with an element of playfulness, reminding me that the work must be valuable to the artist to have any meaning at all. That Prip cares about his work is evident, and that makes it valuable for us all.

- Michael Zimmermann

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The most fascinating aspect of Prip's masterpieces is the use of various techniques, such as twisting, bending and overlapping to establish a certain dignity. My favorites are the simplest in form but contain the most of Prip's effort in the attempt to achieve a solid identity, and he obviously succeeds. In analyzing one of the Overlap Boxes, the object's seams are joined one over another to incorporate themselves with the lid. The result is the development of a harmonious design that never seems to allow the viewer's eye to escape. The integration of the top and the bottom pieces and the slight rise of the circular line, which begins from the lid's edge and tapers off into the shiny surface, lead an observer's view to relentlessly flow along the infinite and successive mode of attention. The circular line may physically cease by disappearing into the lid; however, from that point, the focus is immediately shifted toward another element. So, the process never ends.

- Wonduk Han

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.