Julie Mihalisin

11 Minute Read

"It's one of those childhood memories that doesn't escape you, but I remember being a kid, and I don't remember what it was about, but having my mom say, 'Oh, it's just glass and thinking, 'What do you mean, it's so beautiful.'"

That's how jeweler Julie Anne Mihalisin thought about glass growing up in Philadelphia. Today her silver, gold, and glass brooches evoke the same reaction: It's just glass and it's so beautiful. That response would satisfy Mihalisin because she's a "real truth-to-materials kind of girl" and "…even though beauty is a dirty word in some people's minds, for me, that's what I'm looking for."

But just as glass has never been just glass in Mihalisin's mind, her jewelry is not just jewelry. That doesn't mean that she makes unwearable sculptural statements. On the contrary, she is extremely aware of practical considerations, including the weight and fragility of her chosen material. She is also concerned with formal sculptural issues. She originally chose to work with glass and metal because of their complementary qualities, the transparency of the glass playing off the opacity of the metal. "Glass slumped around metal is such a wonderful juxtaposition of two unique materials," Mihalisin explains. "Metal is so structural; so manmade; so geometric; although it doesn't have to be; very cold and mechanical. Glass is warm; it's human; it's organic." Yet glass and metal also share many characteristics; glass is even referred to as a metal in its molten state.

Despite the original aesthetic impetus and the beautiful, perfectly composed, and skillfully crafted appearance of Mihalisin's work, it is content driven. Its abstract form is a vehicle for Mihalisin's musings on the concept of preciousness and value, made more potent by the form her work currently assumes - jewelry.

Mihalisin's approach is not the well-worn one of using nonprecious materials in a medium traditionally considered precious. "My goal," Mihalisin explains, "is to end up with jewelry that looks like it is made of glass and precious metals, in that order, thus putting the concept of preciousness in aesthetic rather than financial order."

The preciousness comes not from the intrinsic value of glass, but rather from the uniqueness it acquires when subjected to Mihalisin's favored, and now signature, process of slumping - heating glass to the point when the glass begins to soften and sag, but before it has reached an amorphous molten state. Glass when slumped creates an unreproducible result. It is unique and that makes it more valuable and beautiful than diamonds to Mihalisin. "What I think is interesting about my work and what interests me about my work is the fact that every time I slump a piece of glass into a piece of metal, what comes out the other end is going to be different."

The artist's choice of the word metal rather than specifying gold and silver is revealing. Although they could be seen as a counterpoint to the common material of glass, reinforcing her concern with the concept of value, gold and silver are used because they simply work better for the slumping process than a nonprecious material such as steel.

Slumping also embodies something more valuable for Mihalisin than diamonds or gold: time. The process arrests a moment, recording tangibly and permanently something that is elusive and fleeting. "I've always thought being able to freeze a moment in time was wonderful. It talks about movement, about life," the artist stated.

Unlike many artists who always knew what they wanted to do and were supported in their decision from an early age, Mihalisin grew up in a "family of academics." Her father taught physics at Temple University and her mother was an elementary school reading specialist. In her home art was considered something that was done as a hobby, not a career. After graduating from high school and a short hiatus, Mihalisin applied to Tyler School of Art, leaving her fate to the admissions committee. She was accepted and graduated in 1987 with a BFA in jewelry design and metalsmithing.

Mihalisin recalls that she came to jewelry as a result of "a process of elimination. I had taken ceramics, fibers, graphic design, painting, and almost everything they had to offer. Then I tried jewelry and I knew! Tyler had one of the best facilities around and I was exposed to just about every metals technique you can imagine." Stanley Lechtzin was her teacher at Tyler, and she calls him "an incredible professor, so dedicated, so knowledgeable. I really can't imagine getting a better education than I got at Tyler and then going to the RCA."

Mihalisin had tried glass at Tyler, but it was not a happy experience. In her introduction to glass bowling, she burned her hand so badly that she had to drop out of school. That was enough glass for her until her graduate studies in metalwork at the Royal College of Art in London. She chose the RCA because the department was large enough to offer more than one aesthetic point of view. David Watkins (the head of the department) was Mihalisin's personal tutor and there were several part-time tutors plus four full-time technicians. In addition to the faculty, Watkins invited well-known jewelers and metalsmiths from around the world to do short-term residencies, so students were exposed to even more ideas and techniques.

It was at the RCA that Mihalisin began to combine glass and metal. The Platinum Society was sponsoring a competition for first-year jewelry students with a £1000 prize for the best design using platinum paired with an unusual material. In a brainstorming session with the British artist Jacqueline Mina, Mihalisin told her how she "loved the juxtaposition of something transparent with something opaque. She suggested 'What about glass?' That's where I began my experimentation."

Watkins sent her to the glass department where one of the part-time tutors was the sculptor Keith Cummings and with his guidance Mihalisin began experimenting with glass and metal in the fall of 1987. She began with pods of copper and cut slots that the glass could be slumped through. "We started out doing really crude experiments," she recalls. "We were doing things that were six or eight inches long. I kept wanting to try to get smaller and he kept thinking how could you get smaller."

After six months of constant experimentation, spending more time in the glass department than in the metals studio, Cummings encouraged her to continue her explorations on her own. "He was wonderful, very, very helpful, but much that I did and do now, I had to figure out on my own," Mihalisin explains. "Some of the things that I discovered are things that are already known and used typically in glass slumping and then there are other things that I found out for myself, like what I can get away with…"

When Mihalisin was a student at the RCA and beginning her experiments with slumping glass in a metal framework, she was unaware of the work of the American glass sculptors Sydney Cash, known for his lyrical draperies of glass on delicate wire armatures, and Mary Shaffer whose sculptures are bolder paintings of glass and metal, sometimes slumping glass through wire girds or from found tools. Although her work has been warmly received in the glass world (the Corning Museum of Glass purchased three pieces of her earliest mature work) Mihalisin has only recently joined that community. In the fall of 1994 she moved to Seattle, the American center for Studio Glass. Seattle was consciously chosen because "it was a glass community. I felt that I needed to learn more about glass. I have seven years of higher education in metal arts. I'm not saying that I know it all, but I didn't feel I needed as much additional information as I did in the glass." She now work in a building that houses glass painter Cappy Thompson's studio and Ann Welch's glass-blowing shop.

The specific qualities of glass and how it behaves are paramount to Mihalisin's art on a conceptual and formal basis. Talking about her work, Mihalisin says, "I like making pieces that take a form or a concept and repeat it over and over again with just one detail changing…emphasizing the uniqueness of the glass and the process."

That process brings to mind two artists: Lynda Benglis and Sol LeWitt. Mihalisin shares Benglis's obsession with process although Benglis's works tend to be raw and less refined. Aiming for a progressively graduated series of tearlike droops for a brooch, Mihalisin rejected all uneven results, slumping glass until it behaved as she wanted it to.

Like the Minimalist LeWitt, Mihalisin works in series, each one building on its predecessor. She explores many permutations of an idea before moving on. Since her graduation from the RCA in 1989 and returning to the U.S., she has created four bodies of work that she casually calls "droop, bead, inlaid, and current." Each series is based on an exploration of a specific technique, combining increasingly complicated metalwork with slumped glass. But regardless of the form that her work takes, it is always about preciousness.

The droop series from the early 1990s in Mihalisin's most direct in terms of process and materials. Every element is expressed in a straightforward manner. In a brooch from 1994, the truth-to-materials Mihalisin is apparent. With gold wire over copper bands, she tied a slumped glass element to a silver bar. The glass was slumped to organically echo the subtle diamond shape of the silver bar. The slumped form is also very direct, as simple a physical expression of the process as is possible, yet one that is carefully controlled; each droplet of glass on either side of the central drop matches its partner.

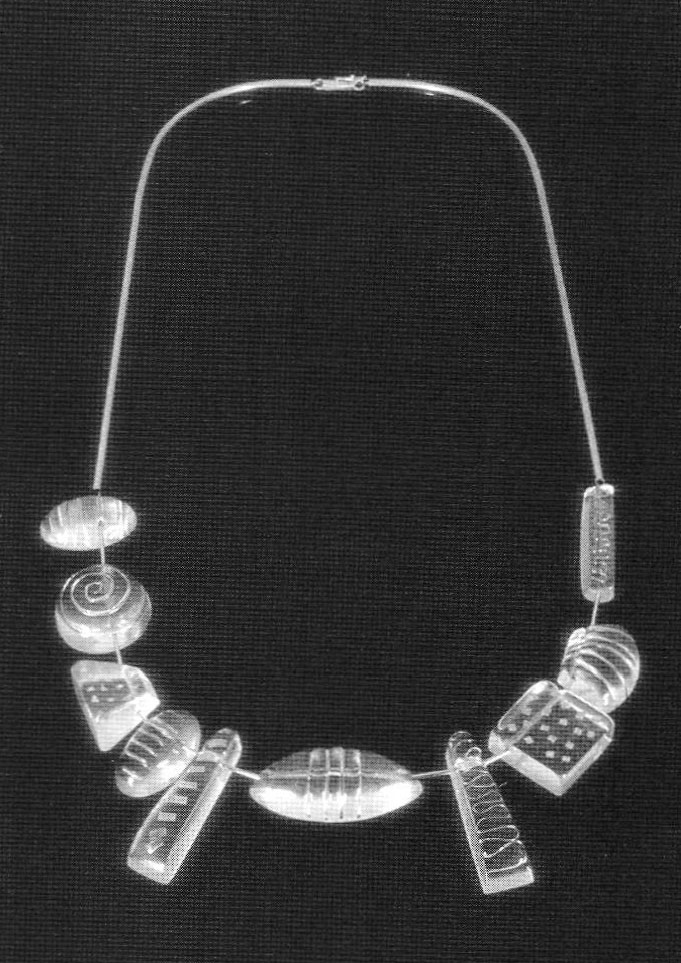

The droop series clearly articulated Mihalisin's concern with process and took the form of very wearable sculpture. In the next series, Mihalisin explored a common jewelry format: the bead. Mihalisin defines bead as an object that can be strung on a chain. Silver or gold was draped in investment molds and glass was slumped into the metal form with an opening for the chain.

The shapes are very dimensional. In a 1993 necklace each of the five sushi-like beads could be described as glass banded with silver, but each one is different. In several the glass is held by thin wires crossing the form or containing it in a grid. In others the glass oozes from slender slits in the metal.

Even though Mihalisin was trained as a metalsmith, in the droop and beads, she concentrated on mastering glass, testing its limits. In the works she calls inlaid, metal began to play a more significant role. She made a married-metal form by using a two-part epoxy-steel mold in a hyrdraulic press. Using the gold outlines on the pressed shape as a guide, she cut opening for the glass to be slumped through. The forms tended to be geometric, often grids or spokes - "common objects," she explains. "The glass reacts in a natural way, a common material bringing life to a common form." In the inlaid works the organic quality of the glass, while still present, was more controlled by the metal framework and began to take on a more gemlike quality, something that Mihalisin tried to lesson by her choice of colors.

With the inlaid works, Mihalisin also began to offer the wearer a chance to participate more actively. In a necklace of seven darkened silver squares, each with a rectangle or square of glass bulging through an opening outlined in gold, the individual parts can be arranged in any sequence, adding or subtracting them as the wearer wishes. They can also be worn as brooches. This adds a gamelike quality to the rather austere but elegant components and helps to emphasize Mihalisin's preoccupation with permutation. The openings for the glass vary in shape, size, and location on the square. Banding the squares are borders of gold-sometimes completely surrounding the square, at other times stopping short. This piece brings to mind the Minimalist painter Robert Ryman. His career has been based on a series of square white paintings of different sized, media, and surface texture (smooth or distinctly brushed), fastened to the wall with a variety of metal or tape attachments. He has reduced painting to its basics - (non)color, support, hanging device - and created a compelling body of work. Mihalisin employs a similar strategy.

In Mihalisin's newest work, she is striving to combine the "raw honesty of (my) early works with the practicality of the recent." The metalwork is finer and more delicate than in previous series. The glass does not look inauthentically precious as in the inlaid works. Glass again asserts both itself and its ability to symbolize time. This series draws on all that Mihalisin has previously learned.

In a 1995 work, eight components can be worn either on the adjustable chain or as brooches, again clearly involving the wearer in Mihalisin's game of theme and variation. Each element is an ovoid or circle and the sizes vary from ½" to 2¾" in diameter. Their orientation may be changed from horizontal to vertical. Embellished with various types of decoration, metal bands of 18k and 24k, silver, and copper constrain by slumping belie any allusion to gemstones. It is much more complicated work than Mihalisin's previous pieces, more decorative; but the formal expression and skilled craftsmanship remains subordinate to Mihalisin's intellectual concerns, the notion of preciousness and what is truly valuable - time.

Karen Chambers is a frequent contributor to Metalsmith and other craft interest magazines. She lives in New York, New York.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.