Kai Chan: Lines of Communication

7 Minute Read

Coming to terms with the work of Kai Chan is not so much a matter of definition as of communication. As Chan explains, "When I work on my pieces, I put things, anything—materials thoughts, accidents—together to become an object that reflects the dialogues of the materials and myself."

Whether a neckpiece of cinnamon held together with elastic bands, or a freestanding bamboo structure, Chan's materials and their freedom in space demand an intimate solitude for full appreciation of their layers of experience.

Born in rural Sechuan, China, Chan left the mainland at age nine for Hong Kong, where he went on to obtain a degree in biology at the university. However, it was not until he arrived in Canada in 1966 to study interior design at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto that he was introduced to contemporary painting and sculpture. Upon graduation, Chan divided his time between the position of the set designer for Toronto's Theatre Passe Muraille and a commercial interior designer.

In 1969 Chan was introduced to fiber art and the "art fabric" installations of Sheila Hicks while vieweing the exhibition "Wall Hangings" at The Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In these formative influences one can see the points of departure from which Chan shapes his lines of communication. There is an interrelationship between fiber, theatre and design as well as material, improvisation and space.

Within a short span of five years, Kai Chan has become a leading creative force in the realm of what Ralph Turner and Peter Dormer in their book The New Jewelry define as "Jewelry as Theatre."

Chan has said, "My artistic investigation began with an attempt to understand space; not as a void but as a visual field. Through the process of using materials I began to observe the perception of space. It is perception that determines space. And perception is affected by the presence of forms and materials." This philosophy is most apparent in Between the Lights, 1985. In this piece, palm leaves have been attached to a cotton core to form two cuffs for the arms. The leaves radiate and animate the surrounding space. Bursts of bright primary color have been painted on one surface, offering an interesting play of light and shadow when the piece is worn.

Chan's materials of choice include rattan, bamboo, dogwood and palm leaves, admired for both their tactility and natural patina. They also become points of departure, in many cases natural imperfections dictating the direction a specific body sculpture will take. His choice of materials is also a natural extension of the calligraphic nature of many pieces. The materials commonly used as tools in Eastern writing ultimately become the language themselves in Chan's hands. There is also a closer link with his personal history, as resilient household utensils were made of bamboo and/or rattan in southeastern China. There is also the poetic process of natural selection. To borrow from Lao Tzu, the ancient Chinese sage, "Be at one with all these living things, which have arisen and flourished, return to the quiet whence they came, like a healthy growth of vegetation, falling back upon the root."

For Chan, the creation of a piece takes on an evolutionary flow, beyond material to movement and bodily interaction. Using his body as the template, he manipulates his materials, constantly trying on the piece and making adjustments. Chan first created his pieces on a whim for a party, and he attempts to recreate this easy dialogue to this day.

Chan seeks to infuse his work with the creative spirit, ultimately passing it on to both wearer and observer. In addition, each piece is constructed to provide a wide range of functional possibilities, not only to reflect the wearer's personality but also to allow for physical interaction with the work. In this respect, Chan is able to convey the essence of what jewelry is—an intimate, portable art.

It is with this point of wearability that one perceives the intrinsic change in Chan's attitude. Whereas the first pieces were produced as show pieces with a nod to drama, he is now connected with how the person actually wearing the piece thinks about it. Above all, Chan would like his work to be a catalyst, enticing the wearer to put it on and have fun with it. After all, as he says, "You're not wearing the crown jewels of England!"

The pieces that invite manipulation are structurally complex. A prime example is Sparkle-Bead-Red from 1985. With its combination of rattan and bamboo loops and coconut beads, a number of variations can be achieved. In addition, the beads glide along the rattan, much like playing on an abacus. Chan's intent is clear, "When you go to the beach and find a beautiful shell, you will pick it up and examine it, play with it, with your fingers, your lips, your ears, nose, your shoulder and your body; you will kiss it, blow air into it, catch it in the air, say a few intimate words to it, and show it to your friends. . . . I would like this piece to inspire the same feeling from you."

Chan has attempted this type of complexity with other materials for more control in variation. A number of "spirals" were executed in papier mâché using a wire frame. Chan actively experimented with this material, mainly for the "springiness" of the shape. The pieces composed of a single strand of rattan sensuously curve over a shoulder, flow with the line of the collarbone or loop over an arm, punctuated by a seemingly effortless flow, back and forth over the body. The lucid landscape imagery of South-Sea-Blue captures this essence as it envelopes the body in an aura of shimmering blue.

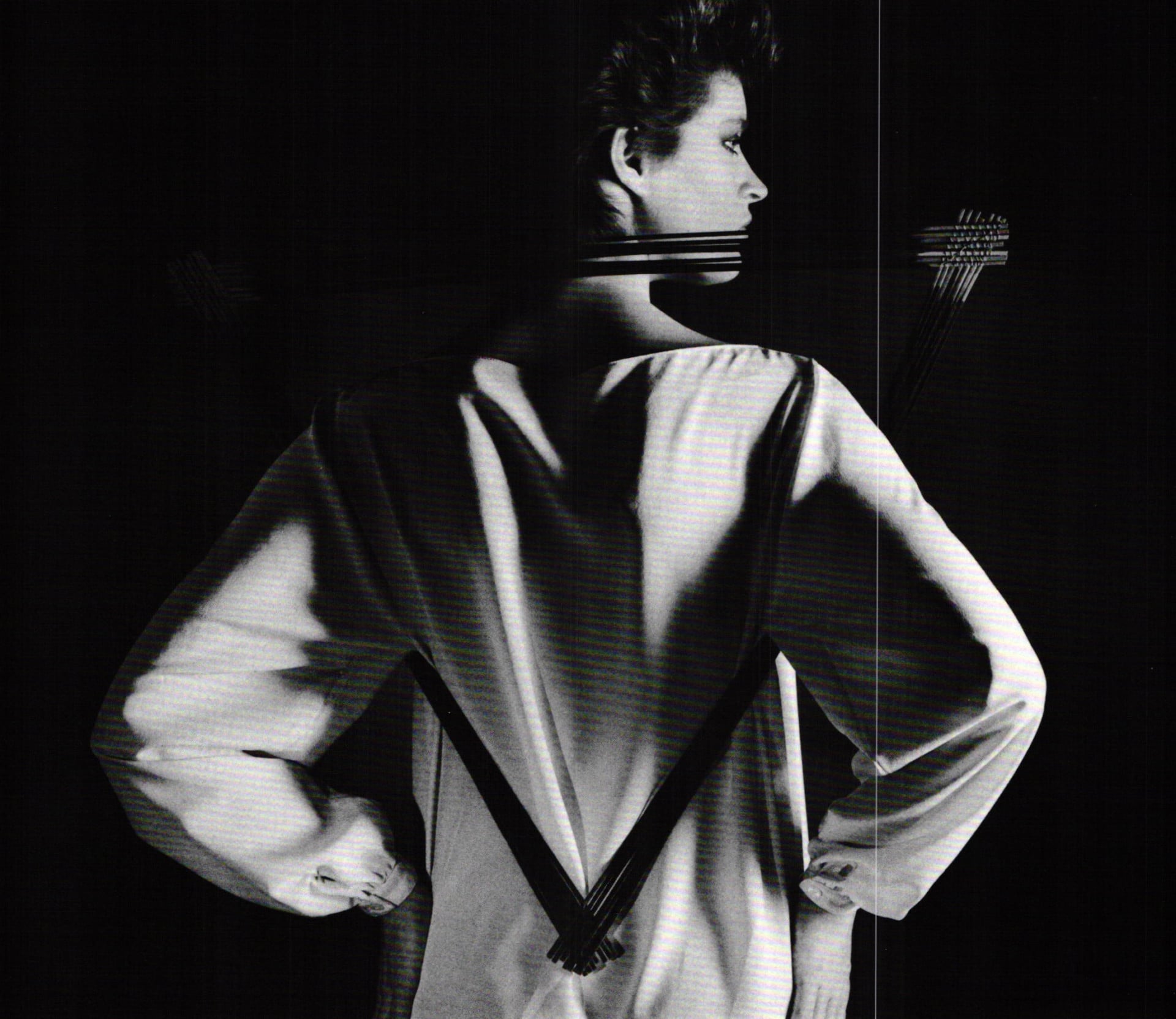

Chan has also experimented with rattan constructions that more preordained in shape and dictate how they are to be worn. One striking example is Neck Harp, in which a curve of rattan tightly encircles the body in a confining configuration, although not necessarily restricting movement. Chan's personal metaphors are the result of a reduction of basic visual elements, be it a landscape, chair or harp. In this respect, he greatly admires the work of Pierre Degen, one of Britain's leading proponents of the "new jewelry," who has removed the traditional limitations of scale and function.

This international influence is evident in Chan's work. Through participation in international shows, he has been influenced and conversely has influenced the contemporary jewelry movement. One international jeweler who has inspired Chan is Otto Künzli. Known for his mannered flaunting of the rules of personal adornment, Künzli has made strong wood pieces that have inspired Chan to comment, "If a woman will wear a diamond, why not wood?"

Color plays an intrinsic role in each piece that Chan creates. It serves not only to enhance the form, but to underline the movement of the piece. While Chan may choose to paint directly onto a work, he has turned increasingly toward using wax and dyes, much like batiking wood. The coloring, however, is never precious.

Another trend emerging from Chan's work is the natural progression from body sculpture to a more formalized freestanding sculpture. All of his works can be hung on the wall or placed on a surface and still successfully animate their surrounding space, yet he has recently begun to separate specific work from the context of body sculpture, most evident with a five-part, site-specific piece at his first solo exhibition at the Ontario Crafts Council this year.

Important in this progression were Night Lines, 1984, a triangular construction of bamboo and silk, which foreshadowed a piece in the show entitled Shelters, and Cocktail Fence, 1985, a witty piece directly akin to Pierre Degen's Ladder Piece and Balloon from 1983.

Beginning with an exploration of nontraditional materials, Chan has pursued a flexible path in the discovery of possibilities for shape, color, and space. His distinctive and calligraphic explorations in space continue to activate and stimulate lively discussion around the definition of jewelry and its expanding parameters. Above all, Chan maintains a quiet integrity and personal joy in animating the lives of others: "My work is: a pet, a toy, a friend, a mask, a memory, a fantasy, a dream, a landscape, a flower, a taboo, a smile, a story, a lie."

Notes

- "Gesture & Form: The Enigmatic Objects of Kai Chan," Helen Duffy, Ontario Craft, Fall, 1984, Vol. 9, No. 3, p. 14.

- Kai Chan: New Works, Alan Elder, Ontario Crafts Council, Toronto, 1987, p. 3.

- Body Works: A Selection of Contemporary Canadian Jewellery, Nancy Tousley, Alberta College of Art Gallery, 1985, p. 16.

- The Way of Life According to Lao Tzu, translated by Witter Bynner, Capricorn Books, 1962, p. 25.

- 10 Jaar Ra, Paul Derrez, Amsterdam, 1986.

- Body Work, p. 16.

Diana Reitberger is Director of Fundraising at the Art Gallery of Ontario and a collector of crafts and photography.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.