Klaus Ullrich: Pioneer and Pedagogue

5 Minute Read

February 11, 1954: "Traces of work appear to be something akin to ornaments of contemporary society. If you, Klaus Ullrich, who until the present day have worked so intensely and creatively along this path, seek new routes for your future work as a goldsmith, you take care of the surface." This suggestion, noted in the diary of Karl Schollmayer, was passed on to Klaus Ullrich around the middle of his course of studies. At the time, the student was thrilled to absorb this tip by his professor and set about putting it into practice independently and productively. It was the dawning hour for a completely new understanding of surface design, as Schollmayer later noted.

Necklace, 1963, 18 karat yellow gold, natural pearls

Ring, 1963, gold, sapphire

Brooch, 1969, gold, stainless steel, spectrolite

Ullrich's teacher in Dusseldorf, who later moved to the College of Design in Pforzheim and also coaxed his student to the Golden City, thus created the basis for a development with far-reaching consequences. But it was a long way from Sensburg in East Prussia to the fateful encounter with Karl Schollmayer. Born in 1927 as son to a doctor a good 100 kilometers to the south-east of Konigsberg in the enchanting landscape of the Masurian Lake District, Ullrich attended the only grammar school in the parish town until he was called up in 1944. After the war and his imprisonment, the family reconvened in North Freesia, where Ullrich went back to complete his university entrance qualifications. Initially, he applied to work for an artistic cabinet-maker, but was rejected. He then did an internship as a male nurse in the hospital in order to then sign up to study medicine in Erlangen.

Brooch, 1969, gold, tourmaline disc, moonstone

Pendant, 1968, gold, tourmaline disc, moonstone

Brooch, 1961, 900 gold, grey cultured pearls

It was a stroke of fate that, in 1947, he noticed an offer for an apprenticeship with a goldsmith in the Husumer Zeitung newspaper, working under Kroger. But he was initially rejected here as well, but then was allowed to commence his apprenticeship, as the candidate who had originally been accepted fell out of favor due to black market trading. Ullrich completed his journeyman's examination in 1950, then worked in Buxtehude; afterwards, from April 1951/52, he worked as a Journeyman for Carl van Dornick in Wohldenberg by Hildesheim. This is where he completed his examination as silversmith. He also encountered Hermann Kunkler there, who shortly afterwards moved to the Art Academy in Dusseldorf, which he also recommended to his friend.

From October 1952, Ullrich visited the goldsmith course run by Karl Schollmayer. At the same time, in 1954, he completed the examination to become a master gold and silversmith before the Crafts Guild and passed the final state examination in July 1954 'with honors'. Ullrich then became self-employed, working in his own studio in Dusseldorf, where, in addition to jewelry he also produced silver implements. An eye ailment (keratoconus) forced him to wear huge contact lenses, so that work was only possible with great difficulty and for brief periods. Karl Schollmayer, who had since advanced to become Director of the Art and Artistic Design School in Pforzheim, remembered his former student in 1957 and, following Reinhold Reiling, recruited him to the Golden City as a teacher for a second class in jewelry and implements.

Necklace, 1966, 900 gold

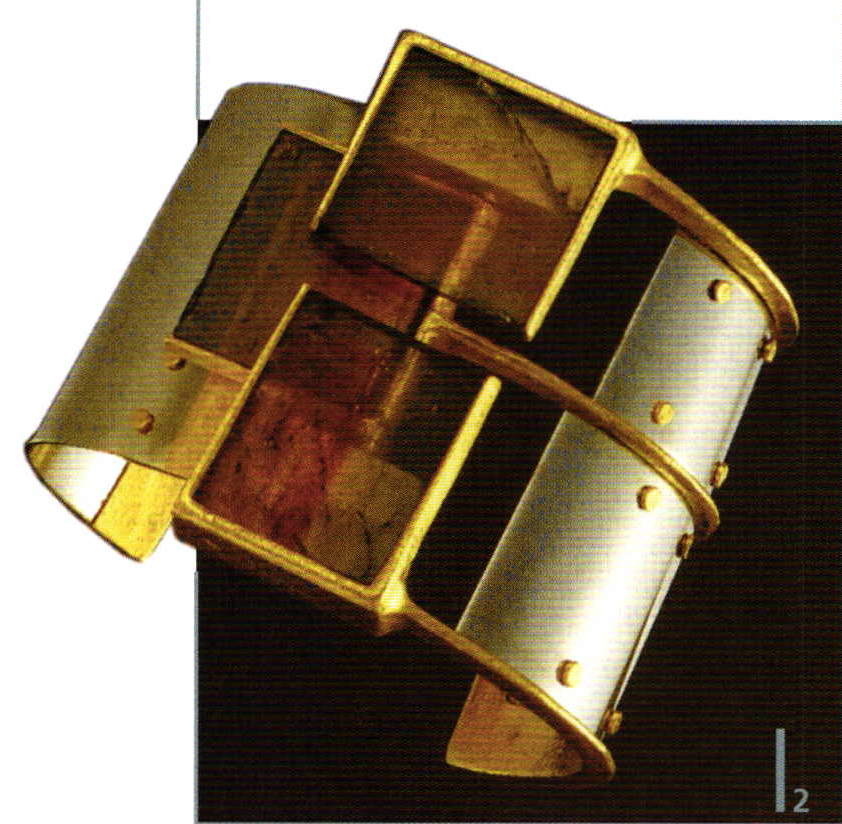

Bracelet, 1971, gold, steel, tourmaline

Necklace, 1967, gold

At the time, Ullrich's eye infliction meant he was barely able to make jewelry or implements himself, but did feel he was able to pass on his knowledge as a teacher. This changed in 1958/59, when corneal transplantations were performed on both eyes, meaning that, with very strong glasses at least, focus of his vision was improved somewhat. In January 1961, Ullrich was appointed professor. Over the course of his 64 semesters teaching, he taught easily 300 students. Scores of them later on themselves became famous names in the jewelry scene.

"Whoever leaves the beaten path and, like you, is open to discoveries, will soon find new opportunities in the direction one has taken," was how Schollmayer once honored the work Ullrich completed. After treating the surfaces with a new form of processing, which the artist simply called 'welding', he soon produced work with applied parallel lamellas in gold. Although their structure shows the closeness to welding, there was another, also new effect: exciting due to the reflection of light. Between the closely applied lamellas, the gold receives a fascinating enhancement, or better, deepening of its own color. Thanks to the use of high quality gold, the pieces become similar to the old gold work by previous cultures, without being stylistically related to them. Another stage of development is the addition of hard metals to the warm glow of the gold. A strong contrast, in which above all palladium and also steel are used. This is where Ullrich's virtuosity is revealed, as he puts together the inherent values of the softer and harder metals to form an exciting play on form with contrasting surfaces. Ullrich's openness toward his artistic environment, coupled with his knowledge of materials and their behavior, are the basis for the style and high standards of the work by the artist "The informal and the tachism in the non-objective art of the fifties, the controlled coincidence in the production of a picture and the controlled and free breaking of a stone when creating a sculpture with other crafts and technical means by Ullrich brought their introduction to jewelry design," judged Fritz Falk, for many years Director of the Pforzheim jewelry Museum, concerning the work characterized by artistic influences from other areas, placing the focus on the human being. Or as Ullrich put it himself. "My jewelry is intended to be a synthesis of contemporary design and wearability; it needs to be understood by the woman wearing it, as it could otherwise provoke her."

Bracelet, 1976, gold, silver, white chalcedony

Pendant, 1991, fine gold, gold, palladium, stainless steel

Earrings, 1987, fine gold, gold, palladium, stainless steel, silver

The artist died on June 19, 1998, due to the consequences of a brain tumor that was recognized too late. With his passing, the international jewelry scene lost one of its most important pioneers for 'modern jewelry'.

by Peter Henselder

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.