Kremlin Armory: The Czar’s Gold

6 Minute Read

The Kremlin Armory houses unique collections of precious items that mirror the artistic wealth of the country and the relations with other people and regions. They include the fantastic testimonies to Russian goldsmith art from the 12th to the 20th century.

The Czars' gold conveys an impressive overview of the development in the gold and silversmith crafts in the East of Europe. Each epoch contributed to the rich variety.

The Kremlin Treasure Chamber is mentioned for the first time in the 14th century. The bijou owned by the Grand Prince Ivan Kalita form the basic inventory of the current collection. This is no coincidental development. This mention is linked to the ascendance of Moscow as a potent, central power. Previously, marauding Mongols and Tartars had time and again led to destruction and had obstructed the development of Russian cities.

However, the dawning age of Old Russian jewelry art is found long before the country achieved political solidification. For example, the Czar treasures include extremely rare items from the 4th to the 12th centuries, which originate from the Black Sea regions and also from Byzantium. Old Russia absorbed the antique legacy of Byzantine culture, whose influences were still growing after the Christianization in the 10th century.

The age of the princes

During the 12th to the 15th centuries, several smaller princedoms vied with each other in Russia. Accordingly, each of them was intent to promote the quality of its own crafts. Aesthetically and technically independent schools of inimitable gold and silversmith art emerged - for example in Nowgorod, which maintained very close ties with the Hanse cities, or also at the court of the Prince of Rjasan, whose treasure was not discovered until 1822.

The rise of Moscow

The Russian princedoms were finally united at the turn of the 16th century: Moscow was now at the pinnacle of the empire. Art and culture experienced a respectable revival there, and the Kremlin court studios became the hub of artistic work. Filigree and enamel work enjoyed their golden age. Enamel shone in a selected range of glowing colors, emphasizing the beautiful design and precious filigree lace. Niello was also one of the most popular practices at the time, which involves blackening artistic engravings. The virtuoso variety of the ornaments and their expressive power remain exceptionally commendable even today. In no other country of the world did this technology have such a tradition within the jewelers trade; a goldsmith art that runs through the various centuries like an unbroken line of tradition. After Moscow, Nowgorod remained a leading center for the production of jewelry during the 16th century. The Nowgorod-based masters joined the finest filigree and cast figures to form remarkable compositions, framing them with pearls and large gemstones.

Unfortunately, with just a few exceptions, the names of the goldsmiths who worked in Moscow during the 16th century are unknown. Hardly any information about them can be gleaned from written sources. Their work bears no stamp or signature. In addition to Russian goldsmiths, the Kremlin studios also employed foreigners. The cooperation with masters in Western Europe during the Renaissance most certainly left its marks on Russian goldsmiths. However, this did not lead to a direct plagiarism. Glyptics was one of the specialist fields. There is no precise information available about when the art of cutting stones emerged in Russia. However, it had already reached a high standard by the 16th century.

The victorious ascendance of enamel in the 17th century

The testimony to Russian jewelry art from the 17th century is more extensive. The masters in this period preserved the highly developed, technical tradition of their predecessors. Characteristic features included joyful, extravagant decoration with vivid ornaments made of enamel and chasing. Pearls were used with a luxurious decadence. Jewelry, goblets and ladles, icons, crucifixes, textiles and objects from all areas of life were richly decorated with gold, pearls and gemstones. In enamel art the masters were constantly looking for new possibilities. Nothing epitomized the powerful artistic expression of this period more than the vivid colorfulness of this technology.

The era of major upheaval from the 18th to the 19th centuries

The epoch of Peter I is the period of the greatest changes, affecting all areas of life in Russian society. This is also expressed in all brackets of art, such as architectural monuments, murals, palaces and the numerous objects of the applied arts. The Russian gold and silversmiths opened themselves to European fashions without denying their own national peculiarities. Techniques such as niello and filigree were improved. At the end of the century the former even experienced a new golden age. Mirroring developments in Western Europe, historism found many proponents in the 19th century - and people looked back once more on the extravagant pomp of previous epochs.

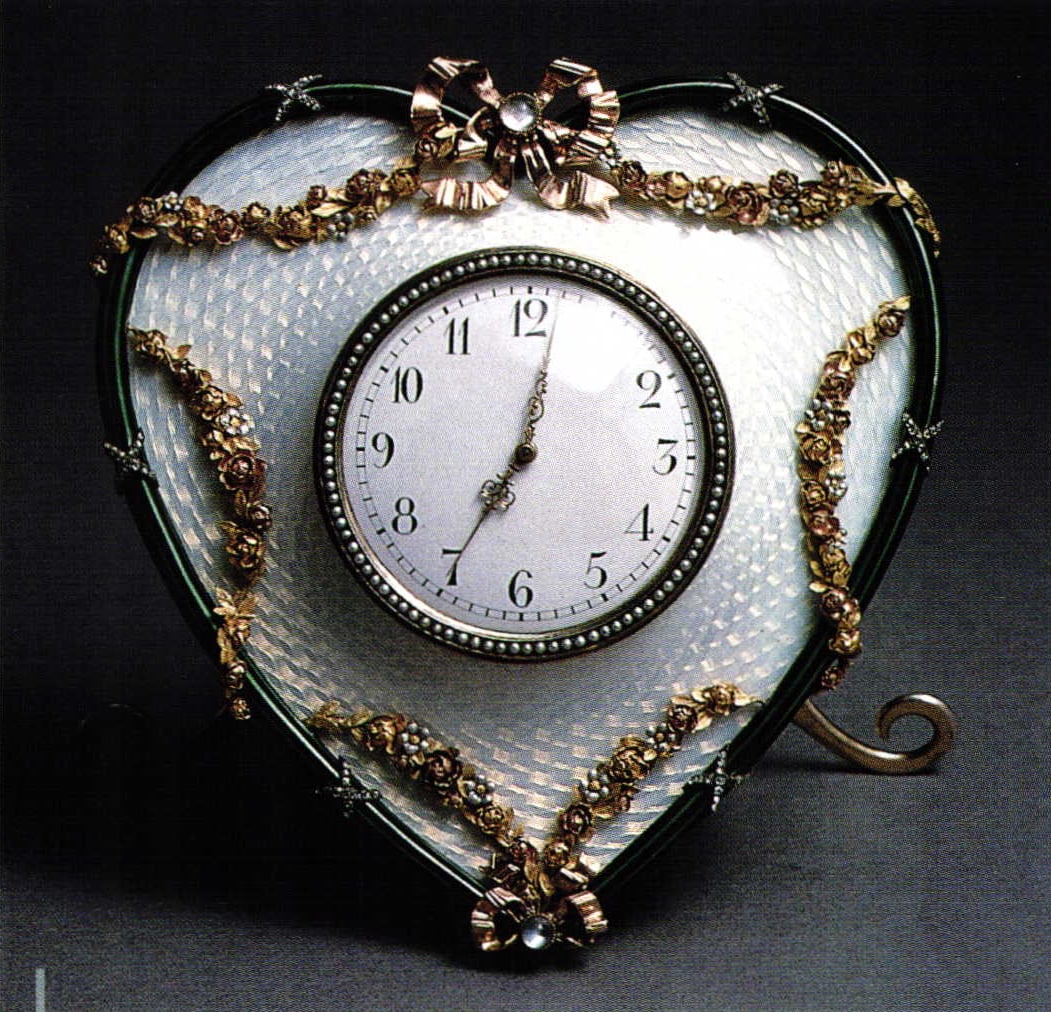

Shortly before the turn of the century, a Huguenot who emigrated via Germany rose to great fame at the court of the Czar: Carl Faberge was appointed court supplier and designed among other things the famous Easter eggs as a gift from the Czar to his wife. In addition, Fabergé also designed one of these precious playthings for the court in 1904: an egg-shaped music box in the heart of a replica Kremlin. The jewelry created by the firm of Carl Faberge, who had enjoyed a fantastic education in St. Petersburg, Dresden and Frankfurt am Main, united in a virtuoso manner the most difficult goldsmith techniques. Their art was renowned in many countries of the world and royal courts in many states drew on the services of the firm, which responded with great sensitivity to changes in taste. It became one of the most ground-breaking entities in goldsmith art at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th centuries.

by Peter Henselder

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.