Laminae Ex Voto

22 Minute Read

Votives are objects offered to a deity in exchange for favor and in the cultures of southern Italy and Sicily, anything can be ex voto. Not subject to liturgical rules, these offerings are made "according to the inspiration and the personal culture of the devotee," defined as "popular religiosity" (Caggiano 39). These ex voto can be as ephemeral as rose petals or as solidly precious as a fabricated silver bouquet. The profusion and variety of such ex voto at the Sanctuary of Madonna dell' Rosario in Pompeii is only partially visible. "If all the gifts brought to the sanctuary ex voto in the course of this century were hung on the walls…the devotees would have one of the richest and most extraordinary visions of contemporary times. The sanctuary would be completely covered in jewels and ingots, watches and chains, paintings and chests, photographs and weapons, written texts and crutches, forming one of the most splendent extraordinary surfaces constructed with all of the visual forms of contemporary communication with the sacred" (Caggiano et al 94).

Votive practices are common in many cultures, from the Latin American Milagro to the Japanese Ema (DeForest). The custom was "common in the classical era", where it was "already considered ancient rituals" (Tiupia 10). "When Naples was a Greek colony the walls of a temple built there by Egyptian worshippers of Isis were covered inside and out by tablets bearing inscriptions or paintings, nailed or plastered to the walls in thanks for favors received. Most of them were put up by sailors who had survived disasters at sea" (Puntillo 27).The Sabellic peoples practiced ver sacrum, a votive made to avert natural disaster or war on behalf of all of the humans and other creatures predicted to be born on their land the following spring. The devotio, practiced by the Romans, offered a life in sacrifice "in order to obtain in compensation the enemy's defeat" (Trupia 10). In Italy the Latin term ex voto is an abbreviation of ex voto suscepto, (according to the promise that was made). While widely practiced throughout Europe until recent times, the "custom has nearly disappeared, except in Italy, Crete, Greece, Sicily, and the Andalusia, Catalonia, and Mallorca areas in Spain" (Egan 12).

Due primarily to their personal and communicative nature, the ex voto amassed by various sanctuaries give us a rich picture of the cultures of their origins and offer insights into the function and strategies of a vernacular based art.

A newsletter, the Bulletin, documents more than 100 years of offerings. Published by Bartolo Longo, founder of the Sanctuary at Pompeii, it is a moving testimony to the history, culture and emotional life of this vital community surrounding the site. In the entries accounts of the miraculous are expressed in the language of factual reportage and include the testimonials of grace that accompanied ex voto offerings from around the world:

"1894…Mr. Vincenzo Enrico, a building constructor in Naples, is always present in our memory for having encouraged us both morally and materially. When we were perplexed at the start of the Works for the Sons of Prisoners, he placed his substantial offering of six thousand lire in our hands in order to obtain grace for his recovery. He was graced and we began the Works…"(37) and; "From Dindigal, India, 1899…a young Indian girl had swallowed three strychnine pellets intended for rat extermination …Miss Mary Higgins, an active zealot of the Virgin of Pompeii, with the parents permission (Protestants …compelled by their love for their little girl in danger of her life, they were prepared to promise anything…), made the child swallow a rose petal blessed in the Sanctuary of the valley of Pompeii…the very same night the little girl was fine…Father Levaux" (34).

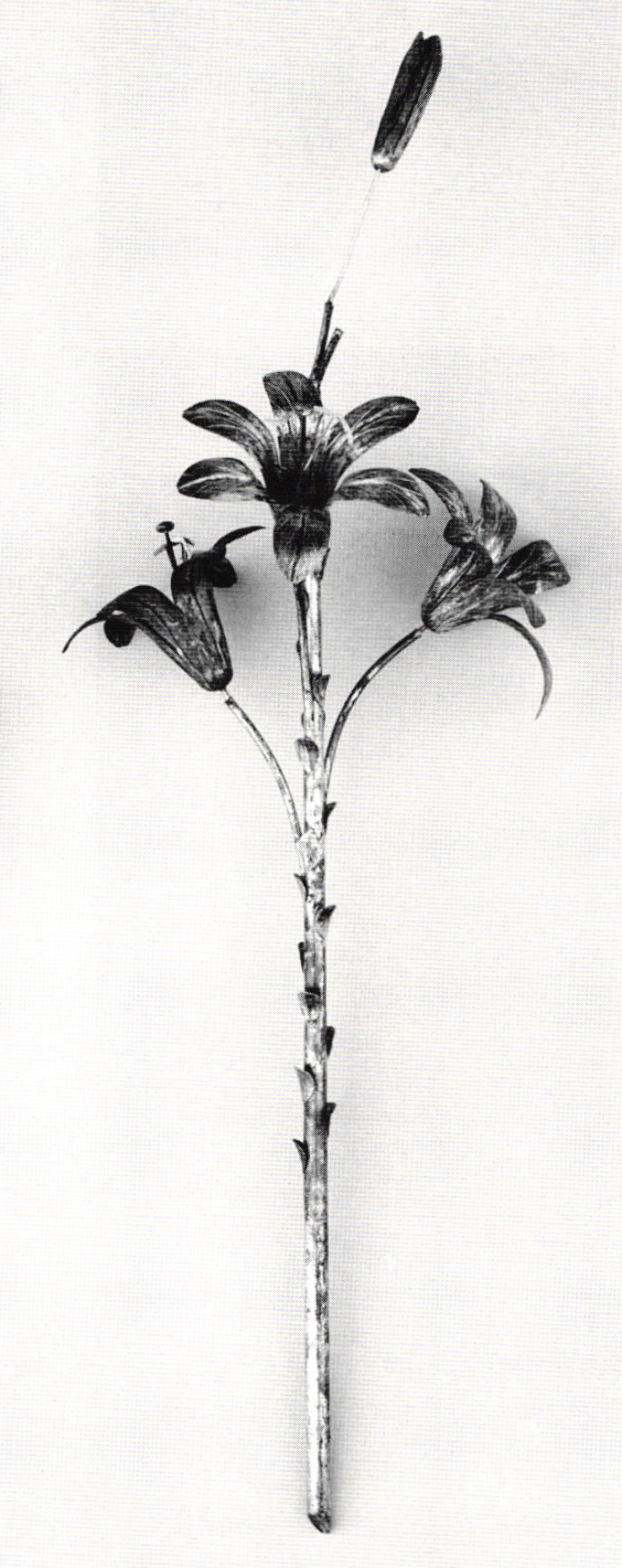

In each town the physical and visual aspects of the ex voto reflect the idiosyncrasies of the local histories and environments. For example, petitioners come from throughout the city and countryside to the sanctuary of Monte Pellegrino in Palermo, Sicily, dedicated to Santa Rosalia. "Ex voto in silver are found everywhere: the most ancient already gathered in windows and glass showcases, laid around the simulation of the saint or hung in disorderly fashion on the most recent walls" (Trupia 10). Ancient clay tablets with renderings of figures and body parts which originated in Mediterranean cultures still remain a strong influence in the sea-hemmed and history-infused regions of southern Italy, and are directly connected to the function and imagery of contemporary laminae ex voto, embossed metal sheets which are produced both by machine and by hand. Examples from southern Italy are highly detailed and beautifully formed. The laminae ex voto evolved during the seventeenth century and most date from the nineteenth (Tripputi).

At Monte Pellegrino most ex voto are laminae with embossed eyes, nose, ears, arms, hands, fingers, legs (with and without feet), feet, abdomens, breasts, torsos, genitals, esophagus, lungs, kidneys, vertebral columns, and uteruses. While factory-stamped versions are numerous, hand-crafted models predominate . The local population of devotees seeking authenticity, and valuing hand-worked ex voto have hired silversmiths in the Castellamare district. These smiths of Palermo are descended from a prestigious artisan tradition dedicated to Argintaria (crafting ex voto) since the 11th century. In an odd inversion, poverty dictates the richness of the expression. "The greater the initial state of privation, the greater the entity of the gift will have to be…symbol of the opulence which springs up, for all to see, from the daily poverty" (Trupia 12).

Located at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, the Sanctuary of Madonna dell'Arco in San Anastasia, outside of Naples, dates to 1450, when, it was reported, a frescoed image of the Madonna was struck with a wooden ball which caused it to bleed. By 1500 the church held hundreds of wax, human hair, and metal ex voto. Miracles at each site are at the center of the rituals and activities that bring concentrations of ex voto. Madonna related miracles are particularly numerous and evince the prevalence of Marian cults. Another legend suggests that this Particular Madonna could be ruthless and her miracles not always beneficial; After a skeptical woman deliberately stepped on and destroyed the wax eye offered as an ex voto by her husband, her feet fell off. They were subsequently preserved in the sanctuary and exhibited in a wire cage ever since 1590 (Puntillo 31).

Most of the ex voto currently displayed at Madonna dell'Arco are nineteenth and twentieth century hand-made and mass-produced sheet silver reliefs of every scale and description. One major section contains images of and pertaining to wars. Some areas are also organized by similarity: children, hands, arms, and horses, while others depend on the chronological dates of the offerings. Enormous wood tympanums are densely filled with arrangements of laminae ex voto; figures, legs, hands, and hearts, both identical and varied, which have been placed at the direction of the priests.

150,000 pilgrims come from all over southern Italy to the annual Feast of Madonna dell'Arco, singing, shouting, and dancing according to ancient rituals to actively pursue connection with divinity. "Despite official vetoes, these rituals are still practiced, evading the strict surveillance of the Dominican friars who have been in charge of the sanctuary for the past 500 years" (Puntillo 28).

In contrast, the nearby Sanctuary of Madonna dell'Rosario in Pompeii was constructed from 1876 to 1887 to be a dignified manifestation of the wealth and rationality of the industrial age. Madonna dell'Rosario was conceived as a missionary work "where the rich and noble families of Naples could worship together with the local farmers" (Puntillo 33). The poverty-burdened peasant culture still "in contact with the remains of paganism springing from the fields of the ancient Pompeii" (Caggiano et al 86), tested the limits of the church's ideological tolerance, which disapproved of the offerings of braids, wax feet, and eyes that were favored by the indigenous population. This merger of belief systems produced a tradition that: "[belongs to the] industrial age, connected in its moments of foundation, diffusion, and stabilization with the logic of industrialism's system of information" (Caggiano et al 53) and is simultaneously a part of the Marian cult which is anchored in an iconographic tradition which owes much to pre-christian paganism.

An illustration of this dual nature is offered in a business-like description of the Record of Graces (the miracles attributed to the portrait of the Madonna of the Rosary transported, by cart from Naples in 1875): "…if we look at the figures on a three yearly basis, we can see that an average of 4 graces per year are documented between 1876 and 1878, which soon become 38 between 1879 and 1881, 438 between 1882 and 1884, and an astonishing 1,119 per year between 1885 and 1887, with consequent, striking increases in the percentages for each 3 year period: 950% (1879-1881), 1,152% (1882-1884) and then dropping to a more moderate rate, stabilizing after the initial boom" (Tripputi 111). These figures are attributed not just to the miraculous powers of the icon but to the wide distribution and popularity of Longo's Bulletin which encouraged even more ex voto.

Ex voto from 1887 on are visible in several areas of the Madonna dell'Rosario (Caggiano).e More than three thousand laminae, repeated versions of silver hearts, figures, and body parts, are arranged in eight lunettes around the transept, placed there by nuns when the sanctuary was restructured in 1939. A gallery of glass cases houses mostly three-dimensional objects which include life-sized, cast silver infants. In the fluorescent-lit halls are an extraordinary collection of highly personalized offerings in frames and cases. These presentations of silver sheets, paintings, photographs, embroidery, fabric, human hair and objects, often organized into collages, offer insights into the history of this community and of the laminae ex voto. AII are evidence that:

"the new world of the devotees was different from the ancient one and powerfully exposed to industrialism's new means of communication - photography, magazines, the first forms of publicity, and above all, the astonishing hyper production of objects. This tradition was itself to make use of materials, techniques, and icons for its ex voto, from the new catalog offered by this great artificial nature being constructed by industrial society" (Caggiano et al 54).

The Industrial Revolution introduced numerous changes into the physical and visual aspects of these collections. While the mass production of stylized human figures, body parts, inner organs, animals, plants, and personal items was possible by the middle ages, the ex voto still were primarily cast or worked by hand.

"Man-made artifacts could always be imitated by men. Replicas were made by pupils in practice of their craft, by masters for diffusing their works, and, finally, by third parties in pursuit of gain. Mechanical reproduction of a work of art, however represents something new. Historically, it advanced intermittently and in leaps at long intervals, but with accelerated intensity" (Benjamin 220).

The thin sheets of silver used in the production of votive objects (laminae) are produced by industrial rolling mills in modern facilities. In the 18th and 19th centuries Italian silver, including religious objects that were being produced in quantity in southern Italian workshops, was "still more decorative and extravagantly ornamental" (Stobart 57) than that produced by northern European craftsmen. This decorative influence combined with the various stylistic revivals that have proliferated in this era, are still evident in the elaborate and stylized images of contemporary laminae ex voto. (The sanctuary at Pompeii may have as many as 10,000 repetitions of some forms.) Flat silver ex voto began to be industrially produced around 1880 (Petagna). Though many continue to be hand-made using traditional repoussé techniques, the low relief of the sheet form is particularly adaptable to production stamping processes. Industrial production of laminae ex voto is centered primarily in northern Italy, while individual craftspeople still produce commissioned works in the south.

In Palermo silversmiths, embossers, goldsmiths, and engravers are responsible for seven phases of a sequence. The fusion, which alloys 1000 grams silver to 250 grams copper (significantly lower than the sterling-level standard set by Frederick II in the 13th century), is followed by lamination, shaping, embossment, refinishing, silvering, and polishing referred to as "the miracle" (Trupia 27-33).

The artisan and the devotee participate in an intense collaboration of craft and content. The craftsperson's skills are engaged on several levels: technical processes, knowledge of a codified catalog of references provided by traditional forms, and as a confidante as the silversmith offers "his interested attention to the story" of his client. In this remarkable interaction "the devoted speaks of himself without reserve," and the artisan and client are united in "solidarity and complicity" in opposition to the church's "persecutorial attitude" toward the ex voto tradition (Trupia 13). The process is prolonged, with multiple visits to monitor progress and make changes. The artisan and patron cooperate to apply the silversmith's expertise onto an object that manifests the devotee's deep spiritual response to a miraculous event.

The personal nature of this process has impacted the gradual evolution and alteration of the traditional metal forms. The details of a particular narrative can be readily integrated by the silversmith with a fluidity unavailable in industrial production. However, industrial forces still pose an important issue. Mechanically produced and hand-formed silver ex voto have exhibited similar changes in recent years. Since the factory can quickly adopt an artisan's modification and reproduce it on a large scale, it is impossible to identify authorship of most innovations. In turn, the silversmith is equally likely to appropriate a manufacturor's innovation. Despite this blurring of the lines of influence, some major trends can be identified. Earlier works include more hand-crafted, detailed, large-scale sheet objects fabricated of silver and occasionally gold. A life-size woman and small child of hammered silver are stunning examples from the sanctuary in Pompeii. The personal immediacy of the figures suggest portraiture rather than stylization, and the marks of hammers and tools are used with great facility to model in relief and render subtle details. Later examples tend to be mechanically produced, hand-sized forms of silver plated alloys. It is difficult to generalize regarding the quality of industrially stamped laminae over time. Even two mechanically produced samples of the same image, both available for contemporary purchase, evince differences in imagery and workmanship. In these pieces both the materials, one sterling and the other plated, and the die-maker's skill in rendering details of hair and subtleties of modeling, demonstrate an obvious range of outcomes via industrial processes. Recently laminae have been incorporated into collage formats. "With industrialism, the symbolic object began to count above all, as the precious materials slowly became property of the masses, and therefore no longer objects of particular worth" (Caggiano et al 79).

While the forms may be symbolic, the subjects depicted are, "sensible things…objects" (Caggiano) not aesthetic, but functional. Different parts of the actual body such as hair or gallstones are equally precious. Historically, the source of much laminae ex voto imagery is the belief that fragments of the devotee's body are the most personal gift, a testimonial to the impossible which has taken place. At the turn of the century the new Madonna at Pompeii was offered "the equivalent weight in silver of the child who had recovered by means of blessing, and devotees nailed thin silver sheets to the wall reproducing the parts of the body struck by illness" (Caggiano et al 53). The silver infant was produced by skilled workers and followed an ancient custom of the devout traditions. The weight of the blessed was in this instance silver, but the practice did not exclude other materials: "some groups offered their weight in cheese and meat, bread and vegetables" (Caggiano et al 76).

The metal sheets are signs of the disease, the sick part of the body "auspiciously detached from the body of the devotee and displayed in the sacred place where they could no longer harm, crystallized in the incorruptible material" (Caggiano et al 76). Many elements of this symbolic body have survived intact from ancient cultures and reference very diverse devotional practices. The body is depicted in three different modes:

"the body of small parts and of internal organs - eyes, lips, breasts, kidneys, lungs, intestines, hands and feet; the body of large parts - the head, chest, back, abdomen, legs and arms; and the body of the entire figure. Almost all these parts refer to a popular ancient anatomy and are synecdoche - parts put for the whole - of illnesses that have struck a zone. The more specialized anatomic details, as the kidneys, the lungs or the intestines, are of more recent design" (Caggiano et al 77).

The heart however, does not necessarily indicate an organ, but is an emblem of sacrifice, recurring throughout the history of the Christian tradition. Appearing in ex voto, it occurs in pictures, tied to cut braids, baby ribbons, photographs, and other contextual materials. Other common images include houses, horses, food, and animals. Some vehicles are also part of the collections of laminae.

Complete figures are often used. Two recurring types of female figures are distinguished chronologically by dress and attitude. Another male, drapery-clad child is visually linked to antiquity. Others wear suits and military uniforms. Newly manufactured soldier laminae still wear old uniforms - the vocabulary of war seems not to require a specific time frame. At Madonna dell'Arco a number of ex voto incorporate beautifully fabricated gold hypodermic needles, visual testimony to a deliverance from drug-addiction.

Old forms are increasingly combined with new materials. Since the proliferation of photography devotees have developed a language of ex voto in collage that articulates specific narratives. Madonna dell'Rosario displays an ex voto which has as its subject an airship accident. There is both a photograph of the aircraft and an image in laminae. A second photograph of the devotee is accompanied by an embroidered inscription which describes the event: "Bombarded by the whole Ala anti-aircraft defense, they were hit several times, then fell from a height of 3000m and were miraculously unhurt. Sky of Pola, on the night of 5-6th August 1915. Ettore Satta" (Caggiano et al 160). All of the images and the text are skillfully integrated into a tri-colored field of rippled satin. Offerings often include:

"newspaper clippings…the symbolic gift of metal plate (laminae)…mixed with the most varied objects of the new material language which utilized pre-printed sheets, medals, certificates, and degrees on parchment with a signed card. The most frequent sequence includes the photo of the devotee, a small image, a silver plate, and a typescript…Its pastiche of images, writing, decoration and objects has, as a model, the material language of publicity and of its displays, the show windows" (Caggiano et al 77).

The ex voto have become frank reflections of contemporary culture chronicling experience with a vocabulary that parallels the structures of both visual art, literature, and popular culture.

The use of photography, painting, and collage as a format for presentation of the laminae objects directly corresponds to presentations of much contemporary visual art. The collections of mechanically reproduced objects mounted as masses of texture and testimony relate strongly to the concerns of installation, offering some of the same opportunities for the creation of a conceptually charged environment through the visual organization of materials.

Still, the ex voto is primarily "a communication" (Caggiano) "a collection of symbol models, which may be utilized as vehicles and channels with which to communicate with the sacred" (Caggiano et al 95). One aspect of the nature of these communications is addressed by Pietro Caggiano in a church publication from Madonna dell'Rosario. He warns that "During the era of 'social communication' one must avoid the potential dangers of the 'depletion of the sign' (The miracle is … an objective sign, that is rooted in the 'fact', not merely tied to the judgment of those who have the power to accept or reject it" (Caggiano et al 23). This statement, referring to the authenticity of the sign gains aesthetic currency when read in relation to the literary structures outlined by Roland Barthes, in his essay "Myth Today". Barthes assumes a commonality of experience that lends conviction to intentionally contextualized communications. Speaking of signifier and sign, he describes the signifier, a bunch of roses, as "empty" without the signified, in his example, "passion". It (the roses) becomes a "full" sign through the author's intention and the references and associations provided by society's conventions and traditions (113). The evolving ex voto tradition of the last twenty years provides innumerable illustrations of a similar use of object/language. For example, a relatively simple juxtaposition of three laminae body signs and a printed image of the Madonna dell'Rosario indicates a complex and poignant narrative without the use of written language.

Walter Benjamin, in his essay "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" states:

"Artistic production begins with ceremonial objects destined to serve in a cult. [And that] "Originally the contextual integration of art in tradition found its expression in the cult. We know that the earliest art works originated in the service of ritual…first the magical, then the religious kind. It is significant that the existence of the work of art with reference to its aura is never entirely separated from its ritual function. In other words, the unique value of the 'authentic' work of art has its basis in ritual" (219 - 253).

The actual ritual objects of ex voto can be examined in relation to this concept of the "authentic". As ancient models of devotion have declined, new models have been synthesized with aura intact and authenticity redescribed. The sanctuary at Pompeii was particularly affected by increased contact with new systems of information and their forms. Designed from the beginning to be open to contemporary changes, it lacked elaborate codes of prohibitions, and was receptive to new varieties of devout expression. Benjamin contends that "that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art…" and that reproductions substitute "a plurality of copies for a unique existence." However, the evidence of contemporary devotional objects points instead to an embrace of mechanical reproduction for ritualistic purposes, preserving their authenticity and aura through "the growth of the devotee's personal labor" and newly interpretive discrimination in their presentation and composition. The contemporary ex voto provides "proof of the search for an individual and irrepeatable contact" often characterized by the "use and occasional re-elaboration of commercial materials" (223).

While the use of sign and symbol in the ex voto tradition is intended to provide instant, transparent legibility its close links to the prevailing culture lead inevitably to tension between ritual formulas and "the pulling deviation of ever new devotees who transfer to the inside of the sanctuary forms and models from the periphery of civil life" (Caggiano et al 96). Over time the conflict between church and community mounts until traditional forms are visibly altered, rendering those that came before illegible. "Hence, the repeated restructuring of many sanctuary interiors and the concealment of entire sections of ex voto, such as wedding gowns, orthopedic apparatus, coffins, cut hair" (Caggiano et al 96) and the use of a new "combination of the irregular and the incoherent in the objects of Artificial Nature" (Caggiano et al 80). The ambiguous messages that result from breaking the rules of a code and that characterize this combining process suggest another shared structure with poetry and visual art. Art can be described as "a way of connecting 'messages' together, in order to produce 'texts' in which the 'rule breaking' roles of ambiguity and self reference are fostered and organized." As Umberto Eco sees it:

- many messages on different levels are ambiguously organized.

- the ambiguities follow a precise design

- both the normal and ambiguous devices in any one message exert a contextual pressure on the normal and ambiguous devices in all the others

- the way in which the 'rules' of one system are violated by one message is the same as that in which the rules of another system are violated by their messages" (271).

"The effect is to generate an 'aesthetic idiolect', a 'special language' peculiar to the work of art, which induces in its audience a sense of 'cosmicity'…that is, of endlessly moving beyond each established level of meaning the moment it is established…of continuously transforming 'its denotations into new connotations'" (Hawkes 141).

This description is an excellent gloss on the conceptual and visual idiosyncrasies of recent ex voto, and a marked contrast to the intentional clarity of earlier models. In this context, the individual messages of the laminae ex voto are sublimated to the devotee's personal sense of overall narrative and visual composition. Use of the silver sheets alone has declined over the last fifty years. However, within the new organizations of materials they retain their meaning as specific signs. They also serve as references to history, industrial society, tradition, and ritual; becoming a vital element in a complex, layered vocabulary of faith that reflects the structures and experience of contemporary culture.

Kate Wagle is a metalsmith and a professor of art at the University of Oregon, Eugene.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research in Italy for this article was supported by a Faculty Development Research Award from the University of Oregon.

My sincere thanks to Professoressa Anna Maria Tripputi of the University of Bari, Milvia D'Amadio, Direttore Storica dell'Arte and Filomena Marcelli, Adetta ai Depositi Etnografici, at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti e Tradizione Popolari in Rome, Padre Ermanno and Padre Guido at Madonna dell'Arco in San Anastasia, Padre Giuseppe Petagna and the gracious staff of the Sanctuary of Madonna dell'Rosario at Pompeii, and particularly to Monsignor Pietro Caggiano of Madonna dell'Rosario for his time and patience.

WORKS CITED

Angiuli, Emanuela. Puglia Ex Voto: Bari, Biblioteca provincial DeGemmis, estateautunno 197. Galatina: Congedo, 1977.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968.

Caggiano, Pietro. Personal interview. 6 September 1996.

Caggiano, Pietro, Michele Rak, and Angelo Turchini. Sweet Mother (La Madre Bella). Pontifical Sanctuary of Pompeii, 1990.

DeForest, J.H.. "Ema" The Votive Pictures of Japan. Charlotte. A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Egan, Martha. Milagros: Votive Offerings from the Americas. Sante Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1991.

Hansen, H.J.. European Folk Art in Europe and the Americas, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

Hawkes, Terence. Structuralism and Semiotics. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1977 Kriss-Rettenbeck, Lenz. Ex Voto, Zeichen Bild und Abbild in Christlichen Votivbrauchtum. Zurich: Atlantis, 1972.

Longo, Bartolo. Bulleting in Longo Archives.

Petagna, Giuseppe. Personal interview. 6 September 1996.

Puntillo, Eleanora. "Ex Votos, of Grace and Gratitude." Italy Italy, Vol. 13, no. 1, February/March 1995.

Stobart, Janet. "Silver for all Seasons."

Italy Italy, Vol. 13, no. 1, February/March 1995.

Toschi, Paolo. Arte Popolare Italiana.

Roma: Carlo Bestetti-Edizione d'Arte, 1960.

Tripputi, Anna Maria. Bibliografia degli ex voto. Bari: Paolo Malagrino Editore, 1995.

_____. Personal interview. 12 September 1996.

Trupia, Joli Scavone. Itinerario di un Cuore, Ex voto e argentieri a Palermo.

Folkstudio di Palermo, 1984.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.