Late Twentieth-Century American Jewelry

25 Minute Read

Signals: Late Twentieth-Century American Jewelry opened at Cranbrook Art Museum in November 1996 - a contemporary counterpart to Messengers in Modernism, organized by the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts from its permanent collection. Signals captures an historical moment as does Messengers in Modernism, but since it is the contemporary moment, there is no accumulated conjecture (a definition of history) to measure it.

The works

Jewelry is a joint endeavor, the wearer is equal partner to the maker. An individual replaces a site as the place of display. The human body as the site of display can mean something different than the human body as a site for adornment. Display brings notice to the object, adornment brings notice to the wearer. In either case accessibility is primary and the visual can not be separated from the tactile.

To be accessible jewelry must be worn, but what are the conditions for wearability? Gary Griffin, curator of Signals, links it to meaning, meaning that the artist projects through the wearer's experience: "It exists outside the image of the work in the private territory where the wearer touches the work and the work touches the wearer…. It locates meaning at the particular site on the body of the wearer which is the only place where the total physicality of the work can be accessed."

Griffin connects the phenomenology of wearing from the maker to the recipient. This is the realm of words; phenomenology is, after all, language retentive. Hayden Carruth ends his litany of the profusion of a May garden: "I am the inelegant gardener soiling my hands in the humus of the alphabet."

How do we experience this private territory of touching? Through weight. When one goes to the museum, they go to look. When one goes to the store, they go to buy. Most likely they will make the decision by trying on a piece. This doesn't take into account that much jewelry is purchased by one person for another. When a man buys jewelry for a woman he might handle it, determining the real or approximate weight on the body, but he is unlikely to try it on. The two experiences can be quite different. The visual experience, the museum or the purchase of a gift for another structures the experience with no reference to tactility.

What I saw in the museum was altered significantly when, after the exhibition closed, I visited the vault and tried on pendants, brooches, and bracelets. Comfort is a desirable attribute of accessibility and comfort is related to weight. The perception and actuality of weight and the interplay between the two are both considered by the jeweler. In Signals much of the jewelry looked heavy, yet each piece was light in the hand and lay easily on the body.

In Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being the dilemma of the desirability of lightness is paired with the unbearable, suggesting that the attainment of lightness cannot be freed from the burden of weight. Periodically Kundera enters the novel to comment on the pleasure of lightness, but the characters' actions and the consequences of the personal and the public carry immense weight. The difference between the actual and the perceived is likewise posed in Signals. Almost all of the jewelry in Signals offers a dialogue between the object and the viewer. Made by the artist and carried by the wearer, the works comment on the human condition with repeated references to mortality.

The human figure dominates Signals. Whether it is the whole or a portion of the body, in piece after piece the body is a vessel registering mortality, sexuality, and everyday encounters. There is discomfort and oddity in the human gesture that stretches from the humorous to the grotesque, from the oversized burdens shouldered by Christina Smith's figures to the downright painful cannonball of Keith Lewis's Triumphant Figure with Willow Wreath.

In each of Christina Smith's three works, Expensive Water, Martha's Vineyard, and Enfranchisement, male figures are off kilter, one foot on a base and one foot falling off; they are barely balancing and hoisting awkward, oversized objects - a bucket or a saucer big enough to be a sombrero which holds a chunky bag of weighty cargo, coins, or jewels. The figure in Martha's Vineyard is bound by a parallelogram of rods that fasten over his torso. These featureless silhouettes are clothed in slightly bulking shirts and trousers differentiated at the beltline. They carry the imprimatur of the 1950s, the clothing suggesting both a uniform and week-end togs. In each instance the figure seems perfectly capable of juggling his odd appendages and yet equally about to be borne away by them. What appears heavy gains desirability because it is actually light.

Signals is loaded with meaning. The phrase points to the ponderous, as if the jewelry suffers under the weight of its well meaning intentions. Sometimes this is true, but much of the jewelry conveys messages through light heartedness, a zestful balancing act, like Christina Smith's pins, that adroitly combines human comedy and tragedy.

Fifteen studio practitioners making jewelry today were chosen for Signals. Almost all the makers rely on images to convey meaning. They are messengers, not of post-modernism or any style or movement, but testifiers to concerns of the day. Their jewelry is made to be worn on the body but it also cites the body as the emblematic visage of the soul and psyche's inner fears and dreams. Sometimes the whole figure is retained, but often only a fragment is shown. And often the part of the body is one that is not visible. Dislocation and reframing are more than strategies, they highlight the text.

Julia Barello's three sterling silver Vascular Studies stand out in the installation because they are accorded different treatment than all the works in either exhibition. Barello's brooches are mounted over x-rays placed in maple frames, which make clear this is the museum's province and not the radiologist's. Three backlit boxes are placed on a wall perpendicular to the rest of the exhibition. The x-rays are more visible than the silver brooches. The effect is striking, but does the medical reference exist without the visual aid? What is more important the medical reference or the jewelry? Exquisitely rendered, the delicacy of the brooches suggests a dogwood in late winter as well as arteries branching into capillaries, though this is muted by the installation.

Sandra Enterline's brooches, Bone Rooms, are pierced boxes of oxidized sterling silver. The porous, mottled surfaces reveal tiny bones. Here the jewelry does all the work. Each is large enough to call attention to itself but small enough to be comfortable and unassuming.

Perhaps it is coincidental, but brooches are the type of jewelry repeatedly invoked to reference the body or a body part. The presentation of the brooch depends on the clothing of the wearer as well as the physical stature and personality of the individual wearing it. The choice of the clothing must be considered, as well as the fact that clothing is an interface between body and world, a layer of tissue that both disguises and ornaments. So too do brooches depend on clothing to heighten or lessen the experience of wearing. Concealment and revelation exist in three layers: brooch, clothing, person.

Daniel Jocz's brooches intimate a dialogue - a pear on a plate, the tips of fingers on a breast, lips overrun with tiny crosses. Lightness in this work is achieved through modeling and substantiated in materials: white gold, gold leaf, fine and sterling silver, luminous paint. Repoussé and chasing create shadows and modulated surfaces. Jocz chooses fragments which hint at a story. The rectangular shapes crop rather than frame the fragments, accentuating the immediacy of the gesture. Each vignette appears larger than the small space it is afforded. The lips, the pear, the breast and fingers manage to be both heavy and light. Milan Kundera, too, moves between lightness and weight to elucidate the unbearable weight, that goal of lightness that lies bare in human exchanges. Early in the novel Kundera states the difficulty in the opposition:

But is heaviness truly deplorable and lightness splendid? The heaviest of burdens crushes us, we sink beneath it, it pins us to the ground. But in the love poetry of every age, the woman longs to be weighted down by the man's body. The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they becomes.

Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.

What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness? Parmenides posed this very question in the sixth century before Christ. He saw the world divided into pairs of opposites: light/darkness, fineness/coarseness, warmth/cold, being/nonbeing. One half of the opposition he called positive (light, fineness, warmth, being), the other negative. We might find this division into positive and negative poles childishly simple except for one difficulty: which one is positive, weight or lightness?

Parmenides responded: lightness is positive, weight negative. Was he correct or not? That is the question. The only certainty is: the lightness/weight opposition is the most mysterious, most ambiguous of all.

The human body serves not only as armature but as metaphor for much of the work in Signals. But other works reflect other imprints of human experience - observance of nature, exchange in the body politic, socially dictated mandates. Jan Yager's silver and gold chicory fragments do not follow the thematic thread of the body, but in materials, lightness, color, and craftsmanship they echo Daniel Jocz's works and so it is natural to address them here. While Jocz compresses the gesture within the geometric, Yager expands the actual through an accurate representation of a part of the plant - a chicory flower, a chicory leaf, a chicory stem in bud. Her choice of plants is significant. Puslane, plantain, dandelion, and chicory are the crop of the roadside and the vacant lot. Yager champions these so-called weeds because they are survivors: they are the plants that she sees in her daily urban trek from home to studio. Her presentation of them is ordinary, that is, the renditions accurately mirror the natural form. They are also extraordinary - Yager's handling of metal, her delicate balance of gold on silver, produce attenuated flowing lines. Like the glass botanical species in a natural history museum, the skill is in the craft and extends beyond it. Parts of the plant are outlined and detailed but the craft does not supersede the knowledge of the plant, the thing itself.

Keith Lewis's Triumphant Figure with Willow Wreath (Self-Portrait) also questions the opposition weight and lightness. The gold wreathed cannonball figure of copper appears shackled, a burden. Tactile examination reveals lightness. Constructed of minute shavings held in a porous surface, an empty interior is suggested. The erratic bent guitar wire suspending the figure also signals the absence of weight. Triumphant in the title posits lightness over heaviness. Without picking up this necklace there is no way to know how heavy it is. It is, in fact, surprisingly light, almost buoyant when worn.

Death and life reckoned in the face of death is addressed by several artists in Signals, but Keith Lewis is the only one who focuses on and speaks out on AIDS and its link to homosexuality. Our Dear Bob and Well Doug, It's 36 Now hybridize human and animal forms, weapons and tools, scars and blood. The ironic titles and Lewis's statement testify to "the ambiguity of being a Queer man lost in Amerika [sic]. As virus and virulence buffet us, I navigate the slipstreams of heart, gonads, and conscious - making jewelry as vessels of memory, quiet calls-to-arms, and talismans of grief."

Lewis's language intentionally weighs down the work, an act which he would probably applaud, as he is of a generation of gays who believe that a silent community must share a measure of responsibility. In the beginning of The Unbearable Lightness of Being Kundera introduces the equation of lightness and weight, speaking neither for one or the another. Even if lightness is the desired condition, lightness is unbearable. It carries its own burdens; the truth of this unfolds in the lives of Tomas, Tereza, Sabina, and Franz. Actions undertaken which apparently produce freedom, a lightness in being, are burdensome and eventually lend weight and reduce freedom. Living for lightness, honoring seemingly enlightened decisions garners only temporary release; a burden descends with crippling weight.

Lewis's language and images, a product of his being a gay man in America, graphically depict a burden. Not lightness, Kundera says later, but heaviness is valued.

Unlike Parmenides, Beethoven apparently viewed weight as something positive. Since the German word schwer means both difficult and heavy, Beethoven's "difficult resolution" may also be construed as a heavy or a weighty resolution. The weighty resolution is at one with the voice of Fate ("Es muss seun!" It must be); necessity, weight, and value are three concepts inextricably bound; only necessity is heavy, and only what is heavy has value.

But the antipodes are never clear. What is heavy appears light, and what is light appears heavy, as in the words of the song, "He ain't heavy, he's my brother." Though lightness is the tangible conditions of this jewelry and this makes them desirable from the wearer's position, they retain visible weight for the viewer. The wearer, the activator of the work, will always be aware of the poles of weight, of the unbearable lightness. And one cannot wear the texts of Keith Lewis lightly.

Actualy texts appear in the jewelry by Kate Wagle and Lisa Gralnick. Each artist is also struck by life's brevity. In R.A.R. the literal is the nursery rhyme "Ring around the Rosey," inscribed on the five bracelet rings intended to be worn as one. One red and four white painted roses are frozen in tiny lucite boxes that dangle from the rings, held together with tenuous fastenings. The kitsch rose pointedly registers as material as well as metaphoric opposition to the beautifully patterned surface of the pendant's case. Wagle's delicate pairing of images and fine craft make the rose as precious as the leaf-patterned case. "Kate Wagle, age 46" appears twice on inner surfaces, the surface worn next to the body. Apparent only to the wearer, the imprint of the artist marks the moment not by date but in the life of the maker. This gentle but startling incision is like memory's beacon in reminding us where we are in our lives. It serves also to remind us we make comparisons over and over - the recalled event to our age at that moment.

If Wagle recognizes the attempt to stabilize the fleeting, Lisa Gralnick in Tomb for Thomas Bernhard pinpoints the end of mortality. Gravity and death's release is entombed in the small text embedded in the locket. The quotation reads: "200 friends will come to a funeral and you must make a speech at the graveside." The number cites the magnitude of the dead's sphere of influence. Yet it is not necessarily the death of someone famous or powerful, but someone who was shown love and trust as evidenced by the use of the word friends. The wearer is you, and you take on the heft of the author's command transferred through the artist.

The texts are messages but not formulas or adages. They must be gleaned, sifted from the particles, just as the dirt, blood, and shredded $50 bill must be sprung from their cases and reassembled in the mind's eye. There is gravity, a dead weight, in the choices Gralnick makes. The money is not simple currency, it is named - $50 bill. That means more than shredded currency.

Plumbobs by definition must be weighty and the one in In God We Trust is equal to the task. The instrument and the body work off the same alignment to the earth as Gary Griffin points out: "A plumbob lets us know that which is erect and vertical. But a plumbob is also a pendulum and it lets us know when the earth moves. As jewelry, it acknowledges movement of the body suggesting dynamics of change."

Sandra Sherman does not cite chapter and verse, but text is alluded to through myth and story, overlaid with art historical allusions. Venus and Cupid takes into account the three-dimensionality of the body in an unusual way. The neckpiece is not simply frontal; it includes the viewer from an angle that the wearer does not see. Wings attach to the chain at the neck and fit the back, as wings properly do. Pushing the limits of ornament, the sheer size of the neckpieces makes them outrageous. The substantial silver wings and big chandelier crystals, watch hands, rose petals, and excessively long chains converge to create a sterling example of the best of dine store jewelry. Neither the construction nor the choice of what Sherman refers to as "mixed metaphors of image, material and composition" is overwrought. The rosettes of found materials are way stations along the length of the chain, and the spacing gives adequate time to travel from one point to the next. It would seem that these neckpieces would be a burden to wear. Yet they are feather light. Still, one must be willing to trade in the comedic and risk kitsch for one could not wear Sherman's jewelry without drawing attention.

Very few jewelers in this exhibition step outside the bounds of metal. Gary Griffin chose not to include works with found objects in Signals because, for one reason, he wished to echo the materials primarily used by the modernists. Occasionally the thing itself, an alteration rather than a copy of a found object presents itself. This quotes Messengers of Modernism. There is Marianne Strengell's choker of hammered washers which calls to mind Annie Albers's humorous but graceful sink drainer neckpiece. Similarly Sandra Sherman's rose petals, watch hands, and chandelier crystals are barely recognizable for what they are, but when recognized they step forth as talismans of the everyday. The currency that Kathy Buszkiewicz uses is not transformed. Shredded and reshaped to create intricate patterns, she arranges the words to reiterate, for example, reserve not reserve. Currency is what we trade with but not what we trade in; the buck stops here. Money does not possess the social significance that objects possess. Money does not indicate what is valued.

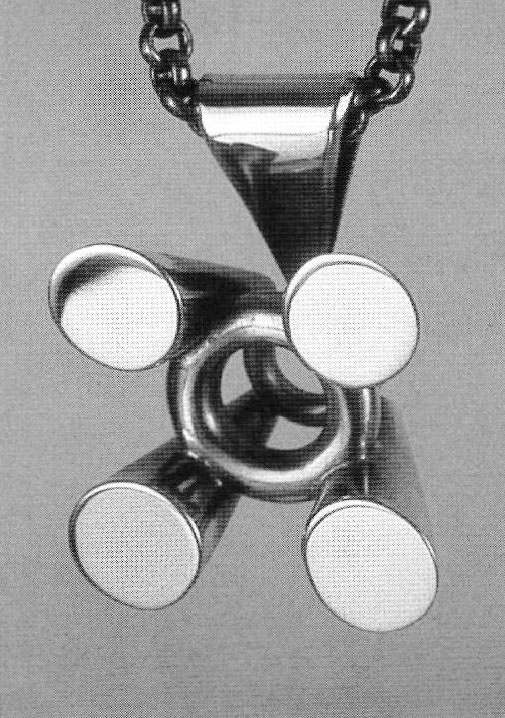

Myra Mimlitsch Gray's four pendants are overscaled prong settings dangling from chains long enough to allow the pendants to cradle between a woman's breasts. Gray sends out zingers on the "actual and implied value of jewelry," as she phrases it. She is effective in her social critique in the several forms she chooses - hollowware, hybridized tools and flatware, as well as jewelry. Her measured economy collapses overstatement into understatement; she remakes the emblematic into an easily missed sign. While it is true that "strategies of formal exaggeration animate the work and enhance the cloying quality found in commercial gemstone jewelry," (her words) this grouping of pendants and chains zero in on the social rites of engagement and marriage which cuts through the entire spectrum of class and economic values. The implied weight of the base for the jewel has the attitude of a big class ring flopping from a chain, a sign of going steady.

In replacing the setting for the gem Gray refers to the aversion to gems that is apparent in Messengers of Modernism and she heightens the importance of the metalsmith/jeweler. Production jewelry may capitalize on human longing through its pervasive commercialization and therefore opens itself to ridicule. Yet it is somewhat faulty to stigmatize assembly line jewelry as uniquely commercial as that of the mass production jeweler. It just plays to a different market, maybe one a bit more savvy, one that likes being in on the barb and takes delight in flaunting the customs that, in fact, this wearer herself likely subscribes to.

The ironic is very tricky territory in jewelry. Critique which targets material culture and the history of the field is besieged by the inability of the insider to ever completely shift to outsider. To wear jewelry is to subscribe to a particular social standing. It is never only ornament and display; jewelry signals status even if it is a statement of anti-status. To wear jewelry means that the wearer is willing to put on the attitude, aims, and production of another human being: the maker of the piece. Such is the case in the Coordinate Necklaces by Erika Ayala Stefanutti. Like Gray's work, these necklaces cleverly connect the significance of the material to the social construct which supports their making. Stefanutti strings together a series of numbers and degrees of latitude and longitude a series of numbers and degrees of latitude and longitude mapping the locations of metal mines. The metal of each necklace, gold, silver, or copper, corresponds to the metal that each mind produces. These necklaces though made of precious metals are not precious looking. In these chokers the letters are small, very flat and thin; they look like cookie cutouts. This nothing special attitude which is also evident in Gray's prong pendants has the virtue of making them wearable in most any instance. They are expensive, the price of the material demands this. The jeweler is caught in the web of her own irony. On one hand, location, the place on earth from whence cometh the material is a homage of sorts, but the metal and its resulting price also force the purchaser into complicity with mining, refining, and the distribution of the material itself. By relating the material to the site one is reminded of differing economies, one nation to another, and the wages of the miner to the wages of the purchaser.

Again the unbearable lightness of being enters. In Signals weight is not in objects but in intention. There is a reversal from Messengers of Modernism's proposition that the body is the badge for the jewelry to the idea that the body is the badge for staging the message. The message of material - metal - is that its cultural significance be translated through its material value. Jewelry here is a willing carrier of meaning.

The exhibition

Only at Cranbrook Art Museum were the two exhibitions paired. Messengers of Modernism, from the permanent collection of the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts, is traveling to nine museums, from Victoria, British Columbia to Padua. Signals is traveling to two different sites.

In a pair neither part can ever be completely separated from its partner. When two are coupled together, it's easy to take for granted the assumptions that go with linking two nouns. For example we know what we mean we say man and woman. Language defines them. Though these terms fester with interchangeable qualities and carry centuries of rigidity that present-day society is attempting to undo, they still make a good example. All the subcurrents stand apart from biological differences.

Signals and Messengers present another pairing, and present a different problem. The words are similar; they both foretell or indicate; they are both nouns. But unlike man and woman, they describe forms of agency. Signals are things, set in motion by humans or natural events. Messengers are people (albeit sometimes heavenly incarnations) who carry information, which may or may not be signals. It is true that messengers may be other than human, turning leaves are a messenger or harbinger of autumn. However, given the two words together, we understand each word according to its most frequent usage. Side by side at the Cranbrook Art Museum, Messengers of Modernism and Signals: Late Twentieth-Century American Jewelry, signals and messengers seem inverted. It is not so much Henry Higgins' question "Why can't a woman be more like a man?" but more a confusion of cross-naming.

When the titles Messengers of Modernism and Signals: Late Twentieth-Century American Jewelry are coupled, the difference in meaning in signals and messengers is borne in the rhetoric but contradicted by the jewelry. In Signals: Late Twentieth-Century American Jewelry, the artists' intentions are demonstrated primarily through image, augmented in form and material. The artist and the intended recipient, where the message will be broadcast from, make human agency the first meaning of messenger, the appropriate one. On the other hand, Messengers of Modernism seems better suited to signals, indicators borne out through stylistic similarity to other aspects of modernism. The jewelry does not carry messages in the sense that Signals does where message depends on a metaphoric and/or narrative dimension.

That aside, the confluence of the two exhibitions side by side is striking. Signals energizes the modernist jewelry, making it exciting to a younger generation not cognizant of this genre of abstraction and modernism. In its perspicuity the installation invites parallels between the two. To look at the fine use of color in the works of Daniel Jocz and Jan Yager helps one see Earl Pardon's achievements in a new light. The modernist jewelers were certainly a varied group coalescing in regional centers. Many of then had other art beginnings and several careers. For a few, like Marianne Strengell, jewelry was a sideline. But they all respected the power of jewelry to magnify the minuscule into an assuming presence. Jewelry was as essential an art form as any other. In the catalogue for Messengers of Modernism Toni Greenbaum quotes Earl Pardon in his belief in the efficacy of jewelry: "In nature and its awesome wonderment I find this equally true - a growth of moss can be visually more significant than a forest; a singular stone can be more interesting than a mountain."

The installation at Cranbrook Art Museum was a visual knockout, enhancing the distinctions of each of the works in both exhibitions. Peter Stathis, Head of 3D Design at Cranbrook Academy of Art, working in conjunction with Griffin and Greg Wittkopf, Museum Director, transformed the spacious galleries, too spacious in their existing configuration for these works, bringing the size down to scale, giving the viewer the opportunity to focus properly on the "growth of moss."

When the two exhibitions opened in November, 1996 at the Cranbrook Museum of Art the installation, in fact, was equal partner to the works displayed. Unsheathed metal studs, rotated 90° from their usual alignment, were hung in close intervals. The resulting free floating steel curtain, suspended with turnbuckles, hovered between the ceiling and the floor. Narrow windows at regular intervals revealed the jewelry. Orange for Signals, violet for Messengers - light and signage separated on exhibition from the other but the repeating stud wall perfectly tied the two together.

The intimacy of jewelry requires diminishing space and the wall worked effectively to focus the viewer. If the sublime is an obstacle to intimate viewing, then its opposite, the ridiculous - the banal vitrine - was also considered. Vitrines were eliminated and supplanted with windows in the wall. This had the curious effect of shifting the museum space to the space of a store. In a subtle inversion, Stathis moved the viewer from the place of worship back to the street, from the place of the unattainable back to dream of ownership.

Jewelry is always about ownership and display. Many different attitudes about jewelry prevail today than the fifties' espousal of delight in the medium. Jewelry came in for heavy criticism in the years between the execution of these two bodies of works. In academic studio art programs there has been a corresponding shift away from jewelry to a more inclusive stance that brings back the forge. Many of the artists in Signals, like the modernists, maintain one foot in jewelry and the other in some other kind of making, or in teaching, or other careers. Still it is clear that they prize the construction of jewelry for its ability to speak large.

Toni Greenbaum begins her essay with a quote written in 1901 by W. Fred, "Modern Austrian Jewellery," in Modern Design in Jewelry and Fans (London: Studio):

Critical examination of the jewellery of any particular period cannot fail to be practically a chapter of the history of culture…. 'Every time has the jewellery it deserves'…for the ornaments worn, whether on the dress, the hair, or the person of the wearer, have always reflected in a marked degree the taste of their period, and are very distinctly differentiated from those of any other time, so that changes in fashion imply changes of a more radical description in popular feeling.

The phrase that stands out is "every time has the jewellery it deserves," the implication being that the historical moment is not simply recorded but that it directs the artist, or the artist is directed by it. If the moment is high-spirited, expansive, and seemingly placid - as it was in Vienna in 1901 and in the United States in 1950 - then the art will also be so.

Keith Jarrett speaking in 1997 in The New York Times Magazine puts a different twist on the adage that every age gets the art it deserves. He says, "There are some ages, I think, that don't deserve art as much as others. I almost thing we live in a time now when that is true."

Margo Mensing is an artist and writer who teaches at Skidmore College.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.