Learning Through Jewelry

11 Minute Read

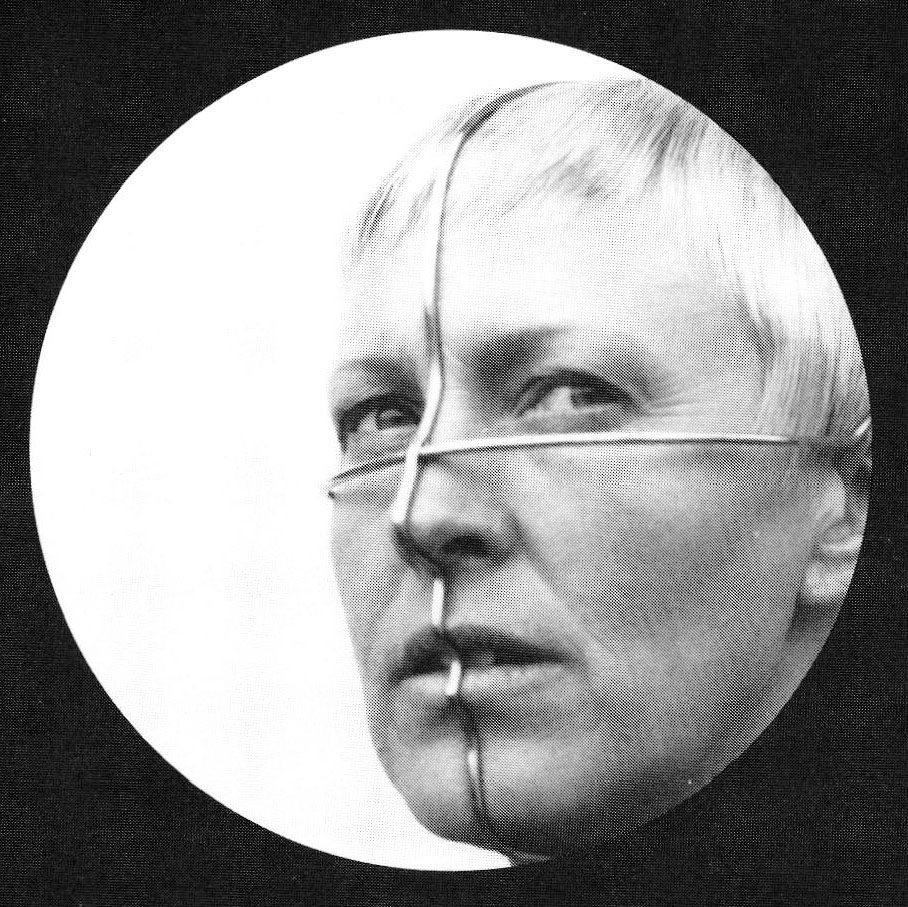

Gijs Bakker's life is inextricably intertwined with that of Emmy van Leersum (1930-1984), but his work has taken an independent course. They collaborated in the early days of their marriage in the mid-'60s, and he was sometimes involved in executing the jewelry that she designed; he also made works of his own that were specifically associated with her, most famously the "Profile Jewel" of 1974. It's a slender steel band that exactly follows her profile from the top of her head to the bottom of her chin, and is held in place by spectacle-like wires over her ears. It has been called a "verbal chastity belt," which may be why she looks so wary in the much-reproduced photograph in which she wears it. He describes it simply as the most individual piece of jewelry anyone could have.

Bakker also has a work life entirely his own, one that has included a broader range than van Leersum's jewelry and clothing. He is accurately described as a designer, although he's best known in the U.S. for the photo-based jewelry he continues to produce and show here with the Helen Drutt Gallery. He has also designed chairs, lamps, loudspeakers, the eyeglasses he wears, and even a house (the final collaboration with van Leersum).

Bakker studied from 1958 to '62 at what is now the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. He was from a non-artistic family - his childhood environment included music and books, but not art - but somehow drawing was the only thing he liked to do, so he went to art school. He had no particular goal in mind and happened to take a jewelry course, where he found his field and his wife.

That last was not quite so straightforward, though. When Gijs and Emmy met, she was 29. He remembers her as being a rather stiff bourgeois lady with a permanent wave and a husband; a former dancer and kindergarten teacher, she was struggling to start out on a new career path. She saw him, he says, as a quiet chap with workman's hands. He was 17 then. When he left the school he spent a year in Sweden studying Scandinavian design, which he thought was the height of clarity and sobriety. On his return to Holland he worked as assistant to a silver cutlery designer for three years. He says he enjoyed the work but the slowness of progress and the atmosphere of working in a factory irritated him and finally led him to break free.

He and van Leersum began sharing a studio in Utrecht in 1965. It was a cellar workshop and sales gallery along one of the old city's canals. There, he says, they were for the first time "confronted with the public." People entering the shop tended to look at how things were being made and not at the finished work in the vitrines. They resented this interest in process and wanted concentration on the object. "We learned from this, but it wasn't pleasant at the moment," Bakker says. "You only know later." He notes that today Dutch artists are more protected by government support, and as a consequence "they don't know what it's like to be thrown to the lions" [the public]. What he and van Leersum learned, he says, was "not to compromise but to be strong in our own convictions."

They discovered that there is always "a gap between you own development in the arts and the public's." They responded by being aggressive, making bigger pieces that would catch people's attention; they weren't interested in niceties. Europe was in political turmoil in the late '60s and they were a part of that counterculture generation. They wanted "to communicate" and they also just wanted to shock, so their first innovation was size and the second was material. Gold was too heavy to make big things with, to say nothing of being too expensive. So they began to look at nonprecious materials.

By this time Bakker had met Riekje Swart, who opened a new gallery in Amsterdam. He was invited to be in a show with two older colleagues, and that show brought him lots of attention, including the interest of the Stedelijk Museum, which was receptive to crafts and design (the museum was known for collecting American crafts, too). One of his unusual pieces at this time was inspired by the stovepipe in an old house: he though it a beautiful and adaptable form, so he made a stovepipe necklace and bracelet. At about the same time (1967) he made an aluminum collar that flared out from the neck in all directions, visually separating the wearer's head from the body so that the head almost seemed to be on a platter.

When Bakker and van Leersum were offered a show at the Stedelijk they showed such works and also told the curator they wanted no glass cases: they wanted models to wear the jewelry. That was unprecedented. In those days, Bakker says, "I thought museum people were like gods. But later I found out that the curator had been stunned and didn't know what to say."

The art world responded favorably to these innovations: Bakker and van Leersum found support among artists, and art critics wrote about the work. Architects were then, and continued to be, their clients. Much of the craft world, however, responded with hostility, declaring that the works did not involve any craftmanship. Bakker points out that the aluminum they were using was, as a material, inferior to gold and silver. It was hard to hammer and then hard to polish. But, he says, they were "stupid" enough to use it because they were driven by the idea rather than by any considerations of convenience.

After these "statement" works, they began to design and produce multiples, bracelets mainly, with the help of two or three assistants. They called their shop a "gallery of reproducible art." They were trying to make jewelry cheaply, so that it could be bought by their own generation rather than by the wealthy. This was social jewelry, expressing a philosophical position of the time and showing that they were up-to-date.

(This issue of social jewelry still interests him today. He says young jewelers now ask why jewelry is so isolated; he notes, in answer, that art has grown that way, too. "You're a part of your time and society" Bakker says. "Artists do not invent out of their selves, but out of their time," he believes. Yet when he looks at jewelry of the 1980s he sees only decoration - no concepts, no contribution to current issues. "Nothing of what is happening shows in jewelry! It's so boring - just nice things," he says, noting the exclusion of Manfred Bishoff and Otto Künzli from this criticism.)

Conceptual jewelry followed the multiples of the '60s. Bakker's "shadow jewelry" resulted from an attempt to find "the absolute minimum of form with the absolute maximum presence of the body." He used, for example, a thin gold wire, which was pushed up on the arm until it was tight and then removed, leaving a groove in the skin. "The older you are the better it works because the longer the imprint remains," he says. This was an effort to "look to ourselves as forms as well as personalities." Another example is that "Profile Jewel" of van Leersum, which followed from a symposium on stainless steel he had attended in Austria. He saw colleagues struggling to work that difficult industrial material according to the traditions of goldsmithing; he tried to think another way. He made a profile for Fritz Maierhofer, who, with his long hair, looked like Christ with the thing strapped onto his forehead and throat, Bakker says.

Bakker's invention of the profiles was no different from how a painter or sculpture works conceptually. He believes that craftmakers are apt to produce work that proves their skills, and he says this attention to craft is a mistake: "If you have skill you're not conscious of technique." On the other hand, over the years he has come to believe that education in basic techniques is crucial. He says he rebelled against his own classical training by not teaching it to his students, but he now sees that as a mistake. He suspects the same thing happened in the U.S., because when he has challenged American students with conceptual assignments, they have spent so much time struggling with how to execute an idea that they have given too little attention to the idea itself.

Bakker's jewelry of the '70s and '80s seems to evade issues of craftsmanship entirely. He has concentrated on photographic images laminated to make wearables of various forms. In the mid-'70s he made linen bibs (tied onto the neck, like baby bibs) printed with a photograph of the wearer's bare chest - male or female. There is an amusing yet almost disorienting doubleness in seeing the clothed person adorned with his or her nakedness, as if one suddenly had x-ray eyes.

Other photo-jewelry includes a series of circular collars entitled "Queens," each of which is a laminated photograph of a woman's mostly bare shoulders adorned with crown jewels. He made irregular-shaped collars of blown-up photographs of flowers in which the wearer's head, in the center, looks like some eccentric pistil. And he has used many newspaper sports images - of divers, pole vaulters, etc. - usually embellished with precious metal or stones (for example, gold wires outline a diver's rippling hair). This is a different kind of doubleness: Bakker makes the object a kind of oxymoron by combining photographic imagery, a commonplace and disposable element in the 20th-century, with such valuable materials. The photographic jewelry is so different in tone from the profiles and the shadow jewelry that one realizes how impossible it is to pigeonhole Bakker.

It was after making his stainless steel pieces that he began to work with industry as a designer. Beginning in the '70s he could support himself from royalties. And he has regularly taught, moving between schools in Arnhem, Eindhoven and Delft. Right now he is not teaching, but he heads the "People & Living" department in an innovative program at Eindhoven. Each department head is a professional who would not have time to actually teach, but who is hired to "give direction." Bakker oversees five instructors, sees the work of the 25 to 30 students, and does final critiques. He participates in "strong confrontations," but he is less involved in students' lives and so has a certain detachment. He goes to the school once every two weeks.

He is also involved in advising industry, but he remains independent in that sphere, too. "It's a constant fight to stay free as an individual," he says. He likes best to sit with a sketchbook, to draw and write. "I think I live in my work, but 80 percent of the time is given to other things, organizing exhibitions, PR, etc.," he says ruefully. He thinks that one must create the environment one needs, because there's always a danger of losing oneself.

So who is he now? "For sure I don't see myself as a goldsmith. I'm very handy but I don't want to be a maker, it takes too much energy. I never wanted to be a little guy behind a bench. I like the activity with the world," he says. Bakker can catalogue his skills and shortcomings: "I'm absolutely not a colorist, so I could never be a painter. Form comes first, and expression of the material itself." His work, like the art he collects, has "no handwriting"; he sees that as a consequence of his time, the '60s, when young people were seeking a universal way of expression, outside of the self. He believes he continues to operate under that orientation, for example in his use of journalistic photographs rather than personal images.

"I'm a curious person," Bakker adds, and that's part of the reason design is gratifying for him: "I have to find it myself." Recently he has done street furniture and lighting fixtures for the city of Arnhem, and lighting fixtures that give structure to a market space in the village of Oostburg. "I don't like to do interiors, but to do environments where there is something to tell. Between industrial designs, which take years, these commissions, if accepted, get done, which is very satisfying." Jewelry, for him, is the most liberating of his activities, like child's play. "All that I've learned in life," Bakker says, "I learned through my jewelry."

Janet Koplos is an associate editor for Art in America.

Notes

Antje von Graevenitz, "Instruments of Radical Thinking," in Broken Lines: Emmy van Leersum 1930-1984, 's-Hertogenbosch, Museum Het Kruithuis, 1993, p. 24.

Interview with Gijs Bakker, Amersfoort and 's-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, June 5, 1993. "Gijs" is pronounced something like "Hice," but with a guttural, throaty "h."

A good source of information is Gijs Bakker, vormgever: Solo voor een solist, the bilingual catalogue of his retrospective exhibition held at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Holland, in 1989. The book and show were both aspects of Holland's Francoise van den Bosch Prize, which he was awarded in 1988.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.