Linda Threadgill: Conceptualizing Ornament

Threadgills keen interest in ornament undoubtedly arises from her longstanding practice of etching motifs into the surfaces of her works, a process that she began perfecting as early as her graduate student days. In 1984, after studying the manner in which printed circuit boards were mass-manufactured, she developed a smaller and more portable version of industrys spray-etching machines. Armed with this technology, easily applicable to a photo-resist technique, she deftly created bas-relief patterns on thin metal plates that could be incorporated into larger and more complex works.

9 Minute Read

LIKE SO MANY other modernist prophecies of irreversible evolution, the eradication of ornament decreed in the early twentieth century proved to be nothing more than a prolonged eclipse. In this century, ornament has been fully restored to the designer's repertoire and the craftsperson's store of creative devices.

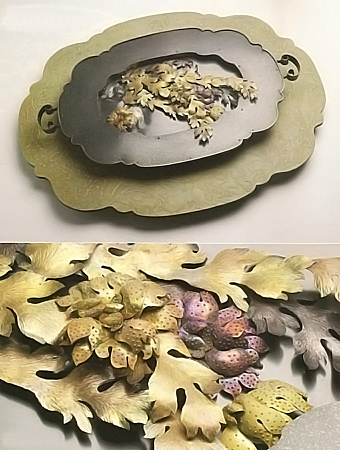

| Florid (tray), 2008 copper, brass, wood 33 1/2 x 42 x 5 3/4″ (with wood base) photo: Eric Swanson | |

| Florid (tray), detail |

And yet, ornament is not entirely what it was prior to its exile during the modern period. Every trip to the abyss entails a certain loss of innocence, and the price of ornament's reinstatement after its temporary fall from grace has been the necessity to justify itself as more than something superficial. Contemporary architects and, to a lesser degree, designers in metals, ceramics, and other so-called craft media have in some cases revived ornament as a multi-tasker that does duty equally in utilitarian and aesthetic terms. In the work of studio artists such as Linda Threadgill, however, the justification of ornament is no simple matter. Instead, it is subjected to a kind of ongoing interrogation that in the end may be sympathetic to ornament's claims of relevance but is no less rigorous on that account.

Threadgill's keen interest in ornament undoubtedly arises from her longstanding practice of etching motifs into the surfaces of her works, a process that she began perfecting as early as her graduate student days. In 1984, after studying the manner in which printed circuit boards were mass-manufactured, she developed a smaller and more portable version of industry's spray-etching machines. Armed with this technology, easily applicable to a photo-resist technique, she deftly created bas-relief patterns on thin metal plates that could be incorporated into larger and more complex works.

| Flower Pendant, 2000 sterling silver 3 1/4 x 2 7/8 x 2 7/8″ photo: James Threadgill | Square Teapot, 2001 sterling silver, micarta 8 x 8 x 8″, tray 9 x 14″ photo: James Threadgill | ||

Threadgill's discovery of Swiss Art Nouveau designer Eugene Grasset's 1897 book Plants and Their Application to Ornament no doubt catalyzed the shift in her work toward a more conscious investigation of the topic in the late 1990s. Grasset's designs, intended for wallpaper, tiles, stained glass, and carved wood, presented ornament specifically in the context of architectural applications. Adopting analogies to these, Threadgill accordingly began to conceive of ornament in relation to three-dimensional space. Her 1999 Flower Pendant, a large articulated, sterling silver floral abstraction, proved to be a crucial transitional piece, in which the etched metal plates were incorporated not as two-dimensional units but rather as the components of a volumetric construction.

| Forsaking Ornament, 2001 brass, micarta, resin 12 x 13 x 9″ photo: James Threadgill |

The connection between surface etching and individual sterling plates in Flower Pendant and related works became vaguely reminiscent of the relationship between wallpaper and wall, as Threadgill began employing the plates not merely as convenient carriers for pattern but rather as structural members of a larger composition. New engineering problems came into play, and she found herself confronting what she has described as a "huge learning curve" on her way to developing the skills necessary to consistently solder the plates together without damaging their delicate surfaces. More importantly, the desire to reconcile two-dimensional decoration with three-dimensional, constructed form demanded a modification of her ideas. Threadgill questioned whether ornament should be considered merely a constituent of surface or, on the contrary, something more conceptually complex.

Threadgill thus directed the next phase of her investigation toward a very deliberate examination of the relationship between ornament and the utilitarian vessel. Reflecting on the practice, common among some historical Viennese silver manufacturers, of offering certain items in both plain and ornamented versions — the first for daily use and the second for formal occasions — she began to consider the function of ornament in the context of social signification. Because utility was not materially altered by the presence or absence of ornament, Threadgill began to consider whether the same might hold true about ornament in the presence or absence of utility. Would ornament continue to be ornament if its relationship to a functional object were entirely eliminated?

| Standing Cup, 2008 sterling silver, brass, copper 12 1/4 x 8 1/4 x 8 1/8″ Photo: Eric Swanson |

In 2000, Threadgill began a series in which sterling holloware utilitarian forms, mostly teapots and pitchers, were surrounded by cage-like ornamental structures reminiscent of decorative antique grillwork. The structures, simultaneously attached to the utilitarian forms and distanced from them by means of unobtrusive struts, were composed of thin silver strips and flat, vaguely leaf-like elements bearing bas-relief patterns. (Given the necessity for strength, these sterling elements were cast in molds taken from thinner, etched-plate originals.) In these works, smooth- walled functional objects and ornament maintained a close proximity to one another — and, therefore, a conceptual association — despite their separation by shallow, intervening space. This space, acquiring architectonic implications in conjunction with the fabricated forms, was key to the compositions. In most cases, Threadgill emphasized these spatial environments by situating the objects on trays or platforms fashioned from a contrasting black micarta.

In 2003, after retiring from a distinguished career at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, where she had taught metalsmithing since receiving her MFA from the Tyler School of Art in 1979, Threadgill and her husband fulfilled their dream of relocating to the warmer climate and artistically rich environment of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The demands of finishing a custom-designed home and spacious studio left little time and energy for other creative output for the next few years, although she regularly engaged in drawing and gave careful consideration to future projects. In 2006, however, Threadgill returned to metalwork with a renewed devotion to the conceptual problems of ornament. In this period, three major series took shape, the first consisting of large, double-walled, openwork vessel forms; the second comprising standing cups with tall, intricately contoured and architecturally suggestive supports; and the third involving broad tray shapes with spatially problematic relationships to abstract floral ornament.

| Conjure, 2008 copper 9 x 17 x 17″ Photo: Eric Swanson | Invoke, 2008 copper 15 x 15 x 14″ Photo: Eric Swanson | ||

In these newest works, she explains, "I'm no longer interested in utility, except symbolically. I may refer to a functional object, often a historical piece, but then I find some way to preclude that from ever actually serving a function."

Despite this assertion, Threadgill has never conceived of the divorce of ornament and function as a permanent feature of her work; in fact, she has already contemplated a future series in which functional objects may be designed to inhabit ornamental still-life settings when not in actual service. For the moment, however, maintaining a degree of separation between utility and ornamentation has proved helpful in the pursuit of a deeper understanding of the latter, primarily because this has permitted her to transcend traditional notions relating to form and surface. Emphasizing complementarity rather than hierarchy in her current work, she has adopted constructive strategies inspired by the Japanese design concept of notan, in which dark and light, positive and negative space, are juxtaposed to create balanced compositions. In theory, at least, this complementarity can be extended to the relationship between ornament and functional form.

In practice, this influence is most evident in four large openwork bowl forms bearing titles, such as Conjure and Invoke, that indicate the degree to which the functional object has disappeared and is now only hinted at by the shapes of the broad fields of ornamentation left behind. These fields, fabricated from hammered copper or brass abstractions of acanthus leaves and occasional rosettes, draw inspiration directly from architectural ironwork. Their relatively large scale — up to 17 inches in diameter — proved challenging to Threadgill, leading her to substitute forging marks for etching and, except in the case of the first in the series, riveting for soldering. In these works notan principles inspire the metalwork, which is constructed as two flamboyant shells, one nestled within the other, consisting of both positive motifs and the negative shapes left behind when these are cut from sheets of brass. Just as importantly, Threadgill has considered the positive and negative effects of light and shadow that these tracery vessel forms produce under certain conditions. "When you get strong light above them, they create amazing shadows," she observes. "I actually designed one with a piece of drawing paper below it so that I could trace the shapes and study the ornament."

Tendentious separation of utility and ornamentation characterizes Threadgill's second current series as well, but here the emphasis is placed on largely two-dimensional representation of functional objects from which ornament has been implicitly extracted. Fundamentally conceptual works, these pieces, including Standing Cup, Counterpoint, and Forsaking Ornament, clearly have less in common with working vessels than with abstractions such as Picasso's famous Glass of Absinthe. Like cubist sculptures, Threadgill's vessels manifest all of the visual attributes of functional forms — containment, volume, surface, and even traditional profiles — yet openly resist the possibility of actual use. The silver bowl of Standing Cup, for example, is inset with an etched plate — a symbolic meniscus — to prevent its ever being fully filled, and the contour-line teapot in Forsaking Ornament is wholly incapable of either storing or dispensing liquid. Significantly, however, as the functional forms in these sculptures condense into schematic profiles in quarter-inch cut brass, they begin to acquire obviously decorative attributes. Ornament, in other words, is stripped from form only to reappear in another guise, as that fundamental form is increasingly simplified and ultimately abstracted.

The third of Threadgill's current series, an oddly effective blend of baroque ostentation and minimalist severity, consists of tray-like brass and copper forms, complete with feet and handles, set on plywood shields that have been gessoed and painted in subtle hues to suggest brocaded tablecloths. Intended to be set vertically or horizontally against the wall like massive rocaille ornaments, these pieces — such as Florid, Circinate, and Spinous — reflect the deliberate negation of function by ornament. The trays seem so intent upon dishing up garlands of abstract acanthus and other leaves — which appear to have detached themselves from the now starkly barren, flat, and riveted rims to accumulate in dry clusters in the wells — that they have clearly lost touch with their inclinations toward any other service. Like Bernard Palissy's sixteenth-century bassins rustiques, Threadgill's trays are subservient to an ornamentation that has become strangely aggressive, even animal-like in its usurpation of the space ordinarily reserved for utility. Ornament, in these works, asserts a will of its own.

These three current series — the first, in which functional form dissolves entirely, leaving ornament as the sole object of contemplation; the second, in which functional forms are rendered as linear abstractions that ironically begin to acquire some of the vague traits of ornamentation; and the third, in which ornament is presented as a vital force that asserts its primacy over what have become fairly blank and sterile utilitarian objects — together constitute a carefully structured and rigorously analytical program of experimentation. In pursuing it, Threadgill directly engages one of the most pressing of issues for those who work in the so-called craft media today: establishing that a fundamental element in the traditions of those media, ornamentation, is conceptually thick despite its associations with the superficiality of surfaces. In her current work, one can hardly question this assertion. Through the intelligence, diligence, and technical precision by which these works have come about, Threadgill has clearly established her position at the forefront of the contemporary investigation of ornament in any medium.

Glen R. Brown is professor of art history at Kansas State University. The author would like to thank the Mark A. Chapman Research Fund.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.