Lisa Norton

16 Minute Read

While Lisa Norton's works give evidence to her interest in the concepts of value, utility, function, form and the cultural conditions in which they were constructed, her points of departure remain rooted in process. Through various techniques she examines both her own personal history in metalsmithing, and the history of metalsmithing as a conduit of material and social culture. While studying at the Cleveland Institute of Art and in graduate school at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, the artist investigated the relationship of the processes of craft production to the function and meaning of craft objects. These investigations led to an interest in the ways by which our culture assigns value to an artifact. In her work, Norton poses questions regarding an object's artistic value as well as its value as a commodity; its intrinsic human value; and its value as a sign of human ethics. She considers the very concept of "utility" as both a function and as an attribute of culture. And in all of her work she addresses craft and technique as processes which have often been thought of as irrelevant to the meanings (outside of pure aesthetic considerations) that we assign to artifacts.

In the last several decades artists, critics, and theorists have rebuked concepts of originality, uniqueness, and authorship as the constructions of an antiquated, patriarchal, modernist agenda. Artists particularly have assumed postures that challenge those previously accepted dictums of creation and the myth of the artist as genius. The hand of the artist: the trace and the mark that recorded their interaction with the medium, once the source of national pride and aspects of art cannot acknowledge the aspects and vagaries of class, gender, behavior and utility that are dissimilar, subtle, and even at times banal, but which reflect material and cultural conditions, never-the-less.

Out of these concerns Norton produced a series of works that resemble Early American utilitarian objects such as water pitchers, oil cans and jugs which, when exaggerated and enlarged, appear almost iconic in their simplification. By removing the object from the realm of practical utility and personal function, the artist provokes the viewer to question: "What human needs does this object satisfy that are cultural, psychological, political?"; thus acknowledging the values that objects serve apart from their physical function. For instance, as cultural signifiers the objects may represent the values of American ingenuity and practicality, or conversely, the values of a private and personal domestic necessity.

Norton's meticulously crafted "common place" objects include Useful Project with Sentimental Appeal, Attractive Project with Conventional Wisdom, and Devise for Separating Lies from the Truth. They were created using traditional, direct sheet metal techniques, which assert the physical processes of making by revealing the lapping, folding, riveting, and soldering of the metal. A vernacular water jug or oil can is seldom considered an object of art; although, they are traditionally viewed as tools of labor and artifacts of low culture. Their utilitarian value is usually defined by the technical and physical requirements of their function, form, size, material, and construction. Norton enlists a form of parody by presenting basic, everyday objects whose associative value to the viewer is more direct, unassuming, and less contrived than conventional works of art. They also function as a nostalgic artifact, and an object presumed to have been used by human hands for a personal function. The viewer's immediate response to the object in an exhibition is to assess their assumptions about the role of an object of art, an object of utility, and both the maker and the use of those objects.

By quoting processes of the Industrial Revolution that have an aura of pragmatism and rigor, the work avoids a connotation that is rooted in romantic nostalgia, and while the shapes resemble those from the past, they are squeaky clean and new in appearance, refusing to be simply a patinated artifact; thus not yielding to our preconceived knowledge of the object's utility or value as an antique or collectable. By revealing its construction, (handmade, but somewhat anonymous in technique) a new history is created, paradoxically acknowledging, in the late 20th century, the hand of a specific maker, and the artist's relationship to the anonymous craftspersons who were overworked, underpaid, and unacknowledged during the early Industrial Revolution.

Like many artists, Lisa Norton develops a work conceptually by initially making preliminary sketches, and then she proceeds to constructed paper and cardboard maquettes. The early stages necessarily involve the artist's ingenuity, spontaneity, design skills, and inventiveness. However, the artist feels her interest and passion for the work wanes when it passes into the stage of precise craftsmanship. She states "the metalsmithing processes themselves often became an alibi for not thinking about what exactly is being created. The laborious aspect of metalworking is half tedium and half myth."

Out of this conflict Norton recognized that not only did she tire of the tedious metalworking processes which tended to make the technique invisible and flawless, but that the audience was not always challenged to consider the range of values that a work contains, having been coddled into a state of aesthetic and technical appreciation. The artist strove to eliminate the consideration of design and inventiveness, at least superficially, by selecting generic, utilitarian forms and etching and/or embossing a diagram of their construction plan into the sheet metal before the piece was cut and fabricated.

Over and into the diagram she inscribed a series of aphorisms which quote a variety of anonymous, yet, familiar-sounding sources. The words speak from two distinctly different points of reference, which are revealed not only by the style of the language but also by the style in which they were written into the metal. As an example, Cheap Project with Heroic Appeal, 1986, is a tin and steel water pitcher whose exaggerated stature of 20 x 18" aggrandizes and mocks function as a paradigm for industriousness and pragmatism. Phrases such as "IN THE ENVIRONMENT OF SERIOUS LIVING THERE IS LITTLE ROOM FOR THE NOVELTY OF TEMPORARY APPEAL" and "A STRAIGHTFORWARD JOB" are stamped into the metal, letter by letter. Another voice, subtlety and non-authoritatively pondering the nature of design and technique, has been etched in a handwritten text. The texts not only intellectually challenge both the utility and the context of the work, but the specific act of reading them puts many viewers in an awkward place where, through the vehicle of cognition and interpretation, they are forced to engage with the piece. This series of works, through its focus on utility in relation to human value and inventiveness and the introduction of multiple authorities through disparate voices both diagrams the making of the piece and foregrounds and textualizes the process of assigning meaning and value.

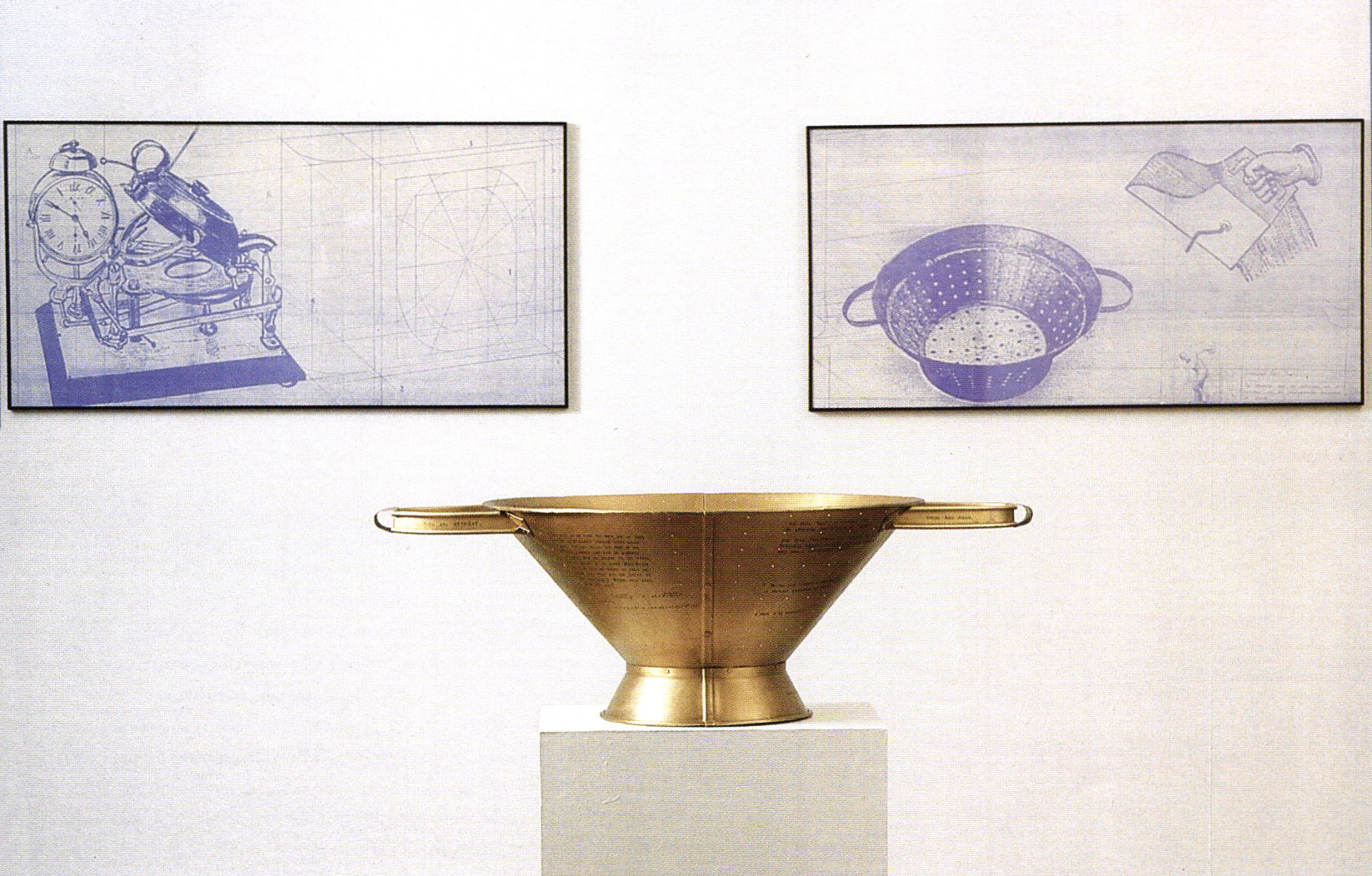

Lisa Norton wants to find a worldly corollary rather than an academic one for her art form. She references not only anonymous makers but also anonymous designers, refusing to only draw authority from an elite world of art historical quotation. The work Studying Lost Time sculpturally depicts a food strainer made hyperbolic by its size, pristine finish and repetitious, linear rows of holes. In this work the diagrammatic element is rendered as in an instructional manual, displayed heraldically around the strainer on two wall-mounted blueprints, which illustrate the physical characteristics and dimensions of the colander, its practical function, and an old fashioned line drawing of a time piece. The bronze sieve is replete with texts that speak of time; however, it is entirely unclear as to which conceptions of time the voices are referring. Clearly the voice of the Industrial Revolution speaks to efficiency, expediency and production as an authority in punctuated blasts: "THE ANTIDOTE IS USEFUL OCCUPATION", or "'LOST TIME'…OCCURS WHILE WAITING FOR SOMETHING TO HAPPEN". Other phrases express a more human element apart from simply one's labor, yet the phrases still have the tenor of wives tales, substituting hollow clichés for genuine reflection.

It is not uncommon for text in various forms to play a prominent role in works of contemporary art. Yet, among many, there is still a prejudice against text because it takes the work out of the realm of the mystical, physically pure aesthetic which both maintains art's exclusivity and special status and keeps it as the product of the Modernist, self-referential genius. Text undermines the purely aesthetic system, demanding that the audience engage and analyze their well-known coded structures of a formal visual language (aesthetics and symbols) and written language(s). The use of words provokes an interpretation that is complex, contradictory and confusing. In Norton's hands it functions to assert what is arbitrary, perhaps banal, and the artist relies on a faith in her audience to challenge absolutes and linear didacticism.

The artist imbeds the words into some of her pieces by rigorously pounding them into the metal, uniting her technical dexterity and finesse and her body to create the work. Ironically, the artist states that she is personally uninvested in the phrases. She claims to select impartially, remaining only an observer, and not wishing to produce a specific meaning or reveal a hidden agenda. Rather, she finds the "words and phrases [which she calls 'sing/songy' and 'useless prattle'] appealing …because they illustrate conflicts."

This distancing is perceived by the viewer in the punning rhythm of the phrasing, and the bi-polar voices that sometimes emerge, neither one pontificating too much. Though, to this writer, it is precisely Norton's clever manipulation and juxtaposition of the visual illustrations, the insidious texts and the meticulously produced utilitarian objects that challenge the encoding or re-encoding of assumptions about industrialized, depersonalized culture. While the quotations sounds familiar, suggesting an authoritative source, the artist remains coy and unrelenting in her refusal to authenticate her chosen sound-bites. This refusal never allows the viewer to identify a point of view or secure a resolution.

Pray for Rain, 1989 displays an enormous copper umbrella which lies on the ground in front of a wall-mounted, montaged blueprint. As in the other multiple pieces works, a polyphonous dialogue occurs between the separate elements, producing neither an interpretation nor a translation, but a rich resonance. The viewer immediately relates associatively to the object, regarding it as a valuable tool used to protect one from the elements of sun and rain, for leisure and golf outings. Yet it becomes a hothouse hybrid of a once useful object. Because of its size and material, it is ineffectual for any utilitarian function.

On the wall is a reproduction in blueprint from the 19th century French painting Paris on a Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte. The image shows a bourgeois couple strolling under two plumped parasols. It is counterbalanced by an ominous, yet comic, satellite dish antennae on the left panel. The image of laissez fare comfort turn the umbrella into an emblem of success and profitability, which is visually and symbolically reiterated by a satellite which carries and transmits the waves of commerce to an industrial society. The artist's use of the blueprint medium borrows from architectural blueprints which control, determine and codify structures and their decoration, embellishment, and ornament.

Conspicuously, the umbrellas pictured also physically serve their users. Consideration of the utilitarian value of an object is generally delineated by its specific function, but here the audience must recognize that the concept of function is expanded by the desires, aspirations and the possibilities of the user. Regarding these objects, Norton suggested: "It is functional like a pot because you still want something from it."

Here again, the metal object is constructed with workman-like techniques, utilizing riveting, folding and soldering. The broadly reflective surfaces are articulated with phrases that reference the umbrella's protective potential as shield, social armor, lightening rod, covering for rain and conductivity. The words also speak from a certain position of paranoia, capitulating to fearful obsessions: "HAVE YOU EVER FELT THAT SOMEONE WAS WATCHING YOU EVEN THOUGH NO ONE WAS PRESENT?", "FEARS OF EVERY VARIETY CAN BE FOUND AMONG US."

These rhetorical phrases might sound to the mind like banter; however, their repetitious utterance has a cumulative effect. The voices can be attributed to essentially two different points of reference yet the historical contexts are not clear. Norton states: "The objective voice often takes the form of a rigid paragraph or sentence. It represents the didactic element in learned canons and codes of behavior and belief. It is a series of assumptions based on tradition and widely held 'truisms' which form the foundation of a society's definition of utility. It can be read as a male voice of authority in a gender dominated culture." "THIS IS DANGEROUS NONSENSE", "RIDE ALONE ON A BICYCLE BUILT FOR ONE" are warnings and ruminations that begin to sound like the phrases printed in daily devotionals for the pious who want uplift and guidance. On the other hand, the voice of the individual who occasionally speaks in the text sounds like the subjective, feminine nature in us all. It serves to jog viewers/readers into a sense of recognition, imparting a critical distance of realism upon the clichés, and functioning through forms of personal observations, opinion, subjective accounts, the incidental and the momentary.

Pray for Rain operates in a cultural moment that does not promote an individual, personal vision; in the way that Caillebotte's society promoted the successes of 19th century positivism and materialism. However the work attempts to negotiate its epoch's prohibitions while recognizing both our distance from and dependence on past belief systems.

Historically, fine metalsmithing has employed meticulous, pristine craftsmanship. The artist has remarked that traditional training in metalsmithing would proceed from the successful cutting of several metal forms, to placing them together, then flowing the solder to merge the metals flawlessly into a visually seamless, pure marriage; and effacing any trace of the connection. The counteract these conventions, Norton regularly uses alternative technologies, such as sheet metal work, a workman-like or a male language, found in heating and air-conditioning ductwork to communicate her ideas. Riveting and folding indicates a kind of pragmatism or obviousness in the way in which things are put together. For Norton this is in distinct opposition to practices such as those found in Danish silversmithing where the work is seamless, aerodynamic and flawless, acknowledging the conception of the designer, but hiding the hand of the maker.

Made by the techniques found in ductwork, Torso of a Young Man, 1990, in elevator bronze, transforms a Y-joint, which is a transition duct, into a modern monumental, Brancusi-like torso shape. Here, once again, Norton asserts a re-consideration of utility, human worth, physical, psychological and philosophical value. All the while, a tongue is planted in the artist's cheek because the viewer's reading of a vessel form is that it traditionally references a woman - a pun on modernism, a pun on text, a pun on surface decoration in general, and a twist on the belief of language being based in authority and male power. Paradoxically, Norton, in her use of these male techniques, pays tribute to the sheet metal workers in Cleveland, whom she befriended, These men, who have gone unheralded, are consummate craftsman, but neither their media nor their names have been enshrined.

Recently the artist has consciously pared down her use of text because she considers it to have become ubiquitous in the art world. The last mentioned series referenced past and received knowledge without using text, refusing to mediate the dialogue with the viewer with the heavy handed authority of words. However, the artist has once again begun to use text, though now she is more restrained in her strategies.

Product with the Influence of Custom, 1991 is a trophy constructed from sterling silver, replicating the somewhat flattened and sandblasted form of the Visible Man, (an educational model of the body and its internal organs from the '60s). He stands on a partial globe as his foundation, wryly inverting the mythic story of Hercules's trials and Atlas's labor. Around the base are inscribed pedagogical and prescriptive remarks about the finished product and its exchange value as a commodity. On the head of the man is a sterling, chambered Nautilus: a decorative symbol used commonly in 16th century metalwork to illustrate the creativity, design skill and technical virtuosity of the maker. Stamped into this shell are the words "ACQUIRED SOLD" which underscore the reduction of much metalwork to its value as a commodity, based on the market value of the precious materials used. Additionally, the words echo society's vested interest in rewarding particular definitions of human worth and achievement.

The artist, aware of her visceral pleasure in working the silver, was also ambivalent about using such a precious material as: "using silver in the gallery world brackets oneself into a relation based predominately on exchange value, and the dictates of wealthy collectors." This personal conflict, share by many metalsmiths, informed the conception of Product with the Influence of Custom. Norton's deliberate and unabashed use of sand-blasting sterling silver to reveal the internal human guts of the trophy/man, however contrived and idealistic they appear, subverts both our historical and contemporary reverence for only that which is mannered, expensive and appears to achieve excellence. The selected texts allow the artist to "beat around the bush" and be purposefully oblique with language; effectively reinforcing and contradicting both our own assumptions, and the form (trophy) of the work itself.

Throughout Lisa Norton's career as a metalsmith one is able to perceive a deliberate denial of much of the sensual pleasure that can be gained through working with particular materials. Instead, the artist is acutely aware of the history of technique and production, the anonymous makers as well as the users and how these histories ascribe value to both art and vernacular objects. She deliberately designs her works to demand techniques that are physically difficult. Yet while her work is large scale, she manipulates her craft with precision, however arduous that process may be. In fact, in discussions she often sounds like an athlete seeking the challenge of a new personal record with little desire for public gain or recognition.

Books on the history of fine arts frequently tell us that there is singular, hegemonic lineage of descent of artistic knowledge and development. (Fortunately, many are currently challenging this conception.) Yet, it is already generally accepted that the decorative arts contain many histories, and, in fact, many now realized that the crafts or the making of useful things, offers a complex record regarding cultural identity and social constructions. In a Post-modern age, Norton acknowledges that we have become unmoored, having lost tract of our culture or, at least, our presumed cultures. However, she is not interested in exploiting this alienation to advance a cultural critique. Rather, Norton attempts to set a stage where the audience can examine and re-learn their knowledge (and perhaps misconceptions) of past personal, social, and artistic histories, histories which remain as the evidence of cultural production and invention.

Michal Ann Carley is an artist, writer and curator living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Her most recent publication was Narratives of Loss: the displaced body.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.