Lois Betteridge: Stretching Material Limits

12 Minute Read

The core of life's work in fine artisanry is the unfolding of a personal style within the cultural milieu of one's time. Exploration, experimentation and sensitivity to material characterize such development. Over the past 30 years Lois Lois Betteridge has developed a particular and distinctive style based on the discipline of working gold and silver.

It is a materials-based approach with its corollary of technique. Through physical interaction with materials, she has honed a modern esthetic that has been derived out of the cold-forming of metals. Just recently, however, at a full maturity of her craftsmanship, she has begun to move away from this earlier sensibility, developing formal qualities no longer so closely allied to the handworking techniques that shaped her original characterization, as well as a more liberal approach to style, which has induced a radical design shift. The intermediary stages of her course have produced a fusion of opposites that expresses a unique vision and a salient hand. This composite style has developed out of an interface between traditional and modern approaches and unifies the polarities of her style.

Early Work: Free-Form Metal

In the goldsmiths lexicon, the slow, laborious process of making usually determines a conservative approach to an individual's esthetics and design sensibility. Ones sense of beauty develops through the characteristics of the material and the material has much to say in determining form. Such is the case with historical work and such has been the case with Lois Lois Betteridge's work. In fact, complex raising problems were the technical challenge Lois Betteridge set for herself in her early work. Construction techniques were not emphasized. As a result, an organic, unconstructed esthetic developed that grew naturally out of the raising technique. A flowing, linear quality was the basis of this early esthetic.

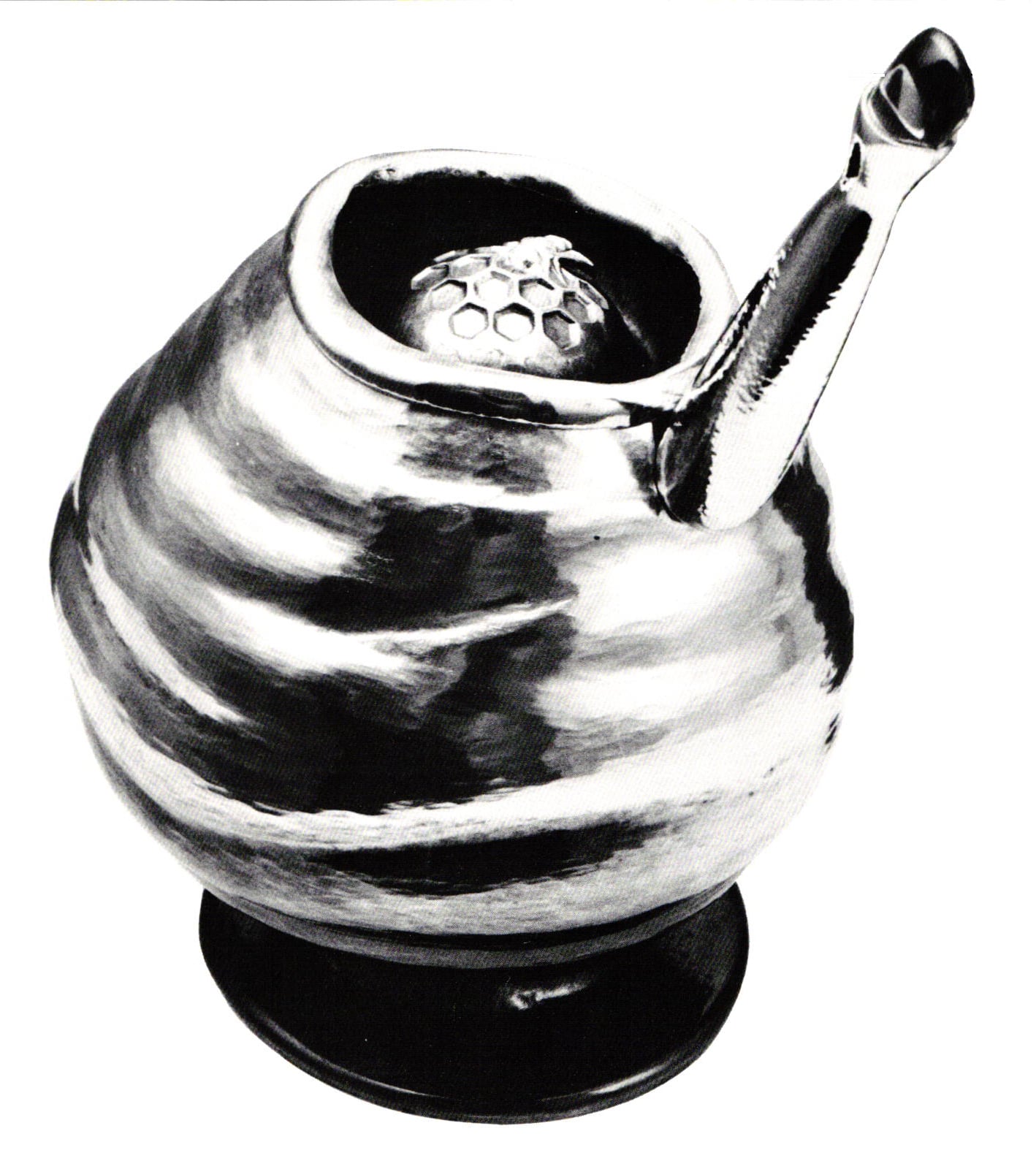

Lois Betteridge's early works developed through disciplined study grounded in such traditional techniques. The Honey Pot and Judaica Spice Shaker are extreme examples of raising. They are tour-de-force objects that derive their esthetic, in strong measure, from technique. Both are based on deeply constructed convolutions, the material being alternately stretched and compressed along determined paths while, at the same time, a sheet of silver is forced out of two dimensions into three. Such handling pushes the technique of raising to an extreme level of mastery and the maleable tolerance of silver to it outer limits.

The repoussé and chasing that shape the surface of the Spice Shaker are as extreme an example of those techniques as one might find in any historical gold- or silverwork. While the Honey Pot is less intense in surface handling, it holds to the same idea of stretching material limits and refining technique as a base for exploration. Alternating ridges encircle a swelling curve, flowing into a counter-curved lip that wraps back on itself to form one circular shape formed at 90 degrees to another.

Tot Cup for an Insomniac fully bridges the gap between playful effect and the seriousness of tradition and workmanship. Clearly masterful in its making, it has a whimsical quality couched in its tipsy form and springy protuberances and a late-night, other-worldly quality in its perforated texture. It is a 20-century equivalent of the kind of serious, but exuberant. precious metal objects of centuries past that were masterpieces of technique festooned with mythological figures and the abundance of nature.

From the Renaissance forward, there are innumerable examples of containers and barely functional objects created in the form of castles, ships, fountains and what have you, chased, repousséd, engraved and set with gems, until the very idea of the piece became subsumed in the excessiveness and joy of the actual working process. Such elaboration of form was very serious, even while employing playful imagery in whimsical juxtapositions. In the 20 century, our esthetic sensibility requires a far sparer object, but Lois Betteridge's tie to such exuberance of the goldsmith's tradition remains.

The point, here, is that technique is a partner in determining form. Tot Cup's asymmetrical shape is based on raising, its lumpy hide is a result of hammering and its accounterments of springs and clock are constructed into the whole. They represent the pushing and pulling of material to enjoy its effect, then working through their results to complete an idea—an idea that is partly the maker's and partly the material's response to being worked. The imagery is playful and the juxtapositions whimsical, but the fact of the piece, itself, is serious.

"Letting the material speak" was, in fact, an approach current in the 60s, when Lois Betteridge was in an early stage of developing her ideas about interactions among materials, design and workmanship. Nature was viewed with romantic reverence and the human hand was expected to play a subsidiary role, enhancing material rather than ordering it. While throughout history emphasis has shifted first to favor the interfering hand, then the dominant material, the two have never been separable until modern times. Hands have done the thinking, as it were, in response to properties of a material and hand tools, being tactile objects, created intimacy with those materials.

Esthetics and workmanship under these conditions are interdependent. Working the other way around, that is, designing for specific symbolic, iconographic or other nonmaterial purposes, and demanding that the material conform to a firmly established idea, results in cerebral, less tactile objects. This is the controlled, designerly approach sought today. It is both mind- and machine-oriented, the mind supplying the directions and the hand being stayed. With industrial methods, the hand is distanced from the material and the interlocking of hand technique and esthetic is broken. The effect produced is entirely different. Spontaneity of workmanship is no longer an issue.

Recent Work: Constructed Geometry

Lois Betteridge's most recent work is characterized by constructed geometric forms. It is, thus, radically different from her earlier work in both esthetic and technical emphasis. That she has chosen to step out of an old model of workmanship and embrace a dramatically opposed esthetic, particularly at the height of her career, is of interest and consequence.

Construction is an esthetic of parts and their relationships. Constructed work has a preplanned quality. It is designed, controlled and dominated by the maker's mind. Given the Modern insistence on spare, clean geometrics, the result does not acknowledge nature. Material is considered and, indeed, even handworked, but it does not speak. While the results need suffer no poor comparison to more freely formed pieces, they are entirely different.

A statuesque silver coffee pot with acrylic accents exemplifies Lois Betteridge's constructed approach. No less technically brilliant than the earlier free-form pieces, the work is, however, about design. It is a relationship of circle to cylinder to rectangle. It is light-reflecting silver played off against dark-absorbing acrylic. It is line worked against form. The balance is formal and rational. Technique is hidden behind design and the older sensibility that bespeaks hands-on material is no longer dominant.

As part of a grouping of type, the statuesque coffee pot is the most formal of a collection that includes a series of copper coffees designed for small-scale production. These coffees represent an approach to industrial method that allows refinement and creativity of design, but bear no relationship to the maker's hand. Sharp-angled, clean-edged and visually active, they whimsically geometric and meticulously functional.

A small tea pot named Madhatter's Tea Party, like the statuesque silver coffee pot, is a showpiece in the geometric manner. It, too, hides materiality behind design. But under the lid, inside the pot, is a doormouse, guest and critic at the original "Madhatter's Tea Party," guest and critic of this one. It is startling or delightful, according to one's inclination. The doormouse is an organic object inside a geometric object and its natural quality counters the cerebral geometry of the container.

Although the maker's hand has actually shaped both inner and outer forms, the effect of an object simultaneously removed from and dependent on handwork remains. The material itself echoes the opposition—a textural and shaggy little object inside a smoothly refined one—a reminder of handwork inside an intimation of hands-off perfection. In comparison to the grouping of copper coffees, this work is still marked by Lois Betteridge's older approach. Nature and the touch of the hand on material show through. It is intermediary between hand and machine esthetic.

Between the two extremes of Lois Betteridge's work are compound pieces, a literal mix of geometric and free forms. In these works, more strongly than in the Madhatter's teapot, an experimental mix of color, material and surface treatment are brought into play. A combination of diametrically opposed forms throws all the pars of a whole work into sharp relief and creates a high level of visual tension.

Perhaps the best representative in this vein is her bon-bon dish Tangled Garden (see inside front cover). A raised floral form is attached through the smallest possible space to a constructed geometric base. The flower flutters open into an undulating rim, the material has been allowed to tear open at one ridge and tendrils of wire float in natural, tangled asymmetry around the whole. Depth and shimmering color are attained through patination and silver plating on copper.

This flower is a result of a material's response to process; stretching, compressing, tearing and coloring have a particular and unique effect on copper. In contrast, the base is a predetermined design, a mathematical pedestal, clean-edged and cerebral. It is visually attached to the floral form by color and by the linear divisions that mark the edges of its constructed triangles. These lines echo and repeat natural textured ridges in the flower's form, eventually flowing out of its top to become the pins that support the flying tendrils. These lines are entirely formal in the maker's concern. They are constructed to fit within a situation. In all, the combination of geometric pedestal and organic flower creates a strong visual tension, and the very small point at which the two meet is a fitting comment on the repose of the whole. The piece is harmonious in a particularly contemporary manner. It is nearly serene in is acceptance of dichotomy and nearly unified in its delicate melding of the two parts.

A combination of geometry and nature is certainly not new to artists. It was one of the great fascinations for Renaissance painters as they developed a mathematical approach to linear perspective and it has been reassessed in numerous stylizations by artists, craftsmen and designers ever since. But a serious interaction of those opposites on an abstract level, an interface of geometry and nature, is not commonly worked ground.

Ritual and Function

Ritual becomes a consideration in Lois Betteridge's bon-bon dishes because of its attachment to function. "For me, the functional object is a way to celebrate the many 'rituals' of our lives, rituals we may not be aware of, but which, when celebrated, become meaningful, beautiful and formal . . ." Ritual formalizes the relationship between function and object and requires the maker to translate effects from the external world into the internal world of the object. The object becomes ceremonial when its function is revered as meaningful and when the maker of the object translates such meaning into refined form and precious dress. The function becomes beautiful when the object is given formal stature and allowed its intrinsic meaning. The external function is internalized as form. The object itself thus takes on a meaning of its own, referring back to the ceremonial activity that has been the impetus for its final form.

Ritual is evident in the fine, detailed touches that are very much a part of Lois Betteridge's work—the elevation of a bon-bon dish, the doormouse inside the Madhatter's tea pot, the gem floating inside the brandy snifter, the bee inside the honey pot, the pedestal under a functional flower-shaped bowl. Ritual encompasses Lois Betteridge's various approaches to esthetics and ceremony governs her decisions in design.

Lois Betteridge's deep attachment to the idea of function is critical to her work. She has stated that she is primarily concerned with the functional object and the importance of this attitude is its impact on her esthetics, resulting in her combinations of abstraction and literal interpretation, symbolism and purely formal design. Function is an integral part of the craft tradition and Lois Betteridge is essentially a traditionalist. For much of her career she has eschewed working outside of silver or gold and this choice has allowed her to unfold a personal style by skillfully working the tactile qualities of those particular metals. While her ideas have taken contemporary form, shaped by the time in which she studied and her own personality, they are informed by the ageless ideas and necessities of function, noble or humble, raised to a ritualistic level and a respect for materials and handworking techniques.

It has been said that the forms of handcrafted work are governed by pleasure and that they transform the everyday utensil into a sign of participation. Lois Betteridge has worked within this ideological context since her earliest days as a goldsmith. Her mature work reflects the thoughtful nature of such a path and a developed sense of the kind of ritual that participation has come to mean, and this is a measure of her success. Yet, her work is also showing signs of formal change and reassessment at a mature point of attainment, and this is the measure of an individual's response to the rapid changes of a modern environment. What remains is the further unfolding of a formal esthetic, whether organic, geometric or composite, which will always be based on the initial premises of pleasure and ritual.

A retrospective exhibition of the work of Lois Etherington Lois Betteridge opened at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Hamilton, Ontario in December of 1988 and will travel to various venues in Canada through 1990. An illustrated catalog with essay by Ross Fox, accompanies the exhibit. For more information, contact the Art Gallery of Hamilton, 123 King Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8P 4S8 Canada (416-527-6610).

Carole Hanks is a teaching master in Art and Craft History at the School of Crafts and Design, Sheridan College, Oakville, Ontario. Her research is concerned with the history of craft and its links with technology.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.