Love’s Labors Lost

4 Minute Read

One of the things that unites practicing jewelers - especially those who given their lives over to the craft - is a deep love for their labor. Curiously, it's rarely spoken of, and never mentioned as a common element that binds the community of makers together. Like most loves, this passion is both a blessing and a curse: thrilling, nurturing, and sustaining; but also troubling, demanding, and inexplicable. And given the intellectual climate of discourse about art, in which any sincere emotion other than angst seems to be deeply embarrassing, the artworld will not help to clarify this thing. If it is to be explained, jewelers must do the job themselves.

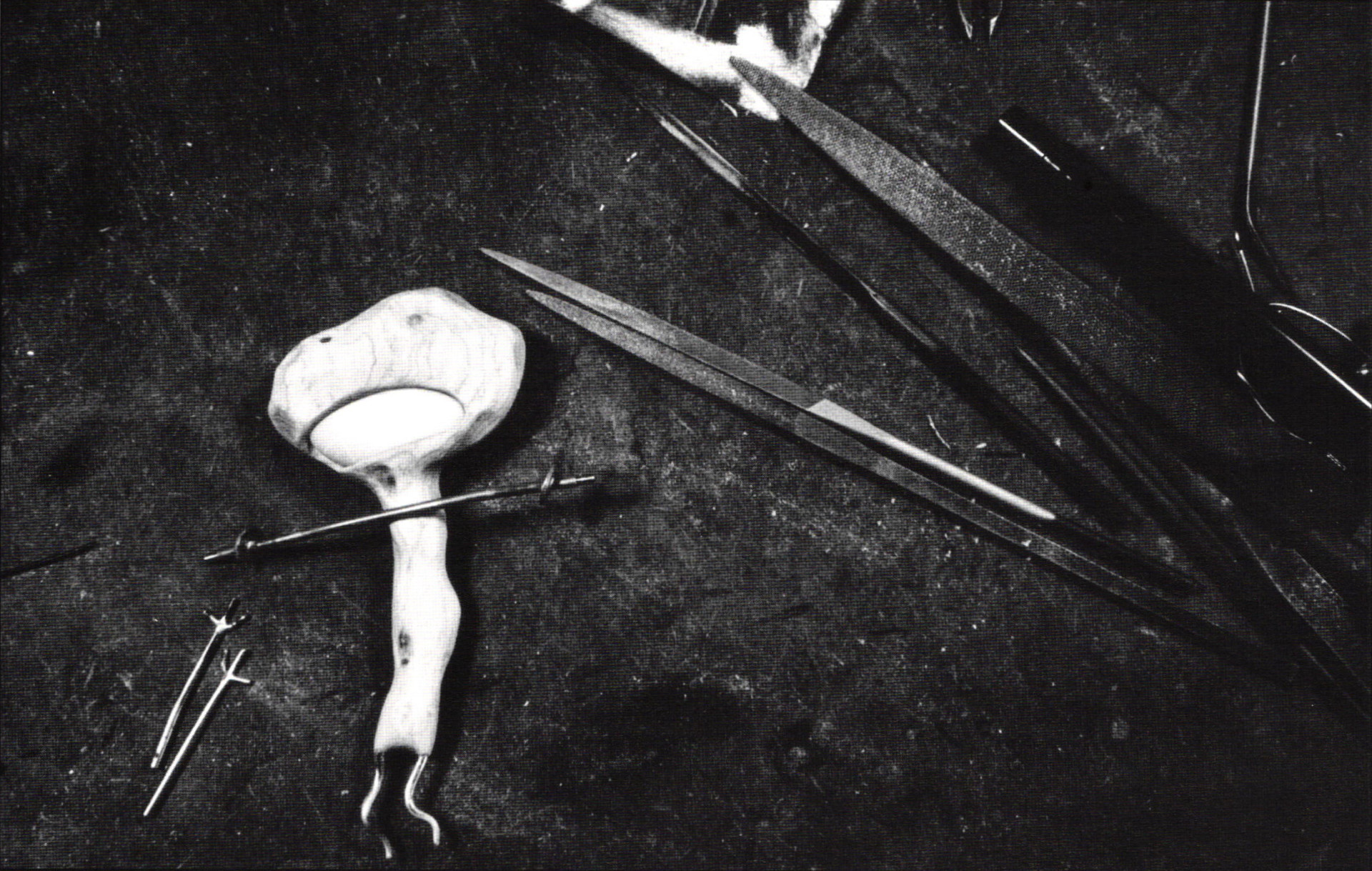

As a working jeweler/metalsmith for more than 25 years, I often wonder about this compulsion that keeps pulling me back to the bench, and once I'm there it refuses to let me do sloppy work. I recognize that there is something that moves me, and I recognize that there is something that moves me, and I recognize its persistence. But I'm hard pressed to say precisely what it is. I think it is a love for making things carefully. It seems to have two components: first, the making of things; and second, the investment of care.

The only writer I know who has considered this question was David Pye, in his book The Nature and Art of Workmanship. Pye speaks of craft as involving the workmanship of risk, in which there is always the possibility of error: the tool slipping, or the hammer missing its mark, or the metal overheating. He opposes this risk with the workmanship of certainty, in which machines can execute the same operation perfectly every time. But within the workmanship of risk, there is both free and regulated workmanship: the former being deft, quick, and immediate; the latter being slow and painstaking. Pye himself was a woodworker and favored a highly regulated approach. In this, he was very much like a jeweler.

Pye never really addressed the fact that regulated work demanded a powerful motivation, and a great deal of care. He presented his own work as if it were dispassionate, mysteriously unmotivated. Certainly, fine craftsmanship can be uninspired, nothing more than a job. You can see that kind of attitude in some trade jewelers: people who put in their daily eight hours at skillful labor, but for whom the craft is a livelihood and not a passion. But there are still a large number of people motivated primarily by their love of the craft. The art-jewelry not out of economic need, but out of desire. They could make better livings in management or sales, but they stick with jewelry-making.

As any good jeweler knows, it's a hard choice to sustain. The craft is a tough taskmaster. Jewelry-making is difficult to learn, time-consuming to practice, and hard to justify to a public that equates handmade objects with mass-produced trash of any kind. It's a craft that demands that you do your best even when you don't feel like it - perhaps especially when you don't feel like it. It's a craft of self-discipline and deferred gratification. Sometimes one must work for days or weeks without pleasure, hoping that a payoff will arrive.

The payoff, of course, takes different forms for different people. For some it is in the absorption of concentrated labor, something akin to the alpha state. For some it is the testing of their own limits, and the knowledge that they have succeeded at a difficult task. For some it is the simple knowledge of having done something well. But for everybody, I think, part of the payoff comes from having invested one's care in the first place. Love is truly its own reward.

The business of caring is difficult to explain. Why do we care? Science is at a loss to describe the cognitive process of learning to care about something, and analysis seems to get us nowhere. My suspicion is that passion for one's craft springs from the correspondence between the skills demanded by the work and the different cognitive abilities hard-wired in the brain. It also has to do with whatever one finds fascinating, challenging, and satisfying. But in the end, learning to care about one's work taps into a deep well of psychic energy. Many of the choices any individual makes flow from that fountain of energy, including most of our artistic decisions - no matter how much we disguise those choices with artspeak.

When the most articulate jewelers and metalsmiths talk publicly about their work, few ever mention why they chose the field in the first place, and why they continue to make jewelry and craft-based objects. They speak in the sophisticated language of semiotics, deconstruction, and feminism, but they refuse to discuss their own motivations. It's as if they are embarrassed by the subject, or struck dumb by their own emotional condition. Should we speak of love and passion? How retardataire!

Personally, I have come to believe that present-day studio craft is build on a foundation of caring, of love for one's work. Nobody reading this magazine is a craftsman by necessity, but by choice - and that choice is made for emotional reasons, not logical ones. So, the craftsman/intellectual who refuses to speak about their passion, is denying the source of many aspects of their work. More and more, I find this denial dishonest.

I look forward to the day when people can speak about their love for the craft openly, but without mushiness or psychobabble. When that day comes, we can begin to talk about the true meaning of craft in the 21st century. But not until then.

Bruce Metcalf lives, labors, and loves in Philadelphia, PA.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.