Mac McCall: Wizard of Ambiguity

8 Minute Read

Mac McCall is a Western shaman, or, as Elizabeth Sasser claims, a wizard of ambiguity. In this focus, she offers an inside look at the workings of his current jewelry, which, in many ways, forms a mythic narrative drawn from cultures separated by time and distance: the American West, the Shogun Era, Roman Antiquity.

But, like that of any good shaman, there is an "edge" to McCall's story, beneath the material patina a trenchant message which he articulates clearly:

"The art which intrigues me particularly, is based on a referential or representational mode: It elicits a response that goes beyond a simple appreciation of, or, esthetic comment on the information presented about the subject."

In Lost Language of Symbols, Harold Bayley has called language "fossil poetry" in which "every word was originally a poem embodying a bold metaphor." Visual symbols do not fossilize; spirals and tectiforms and meandering serpents are regenerated from millennium to millennium and from generation to generation. Each marking seems to accumulate power as it becomes encrusted with myth and modern archaeology. California metalsmith Mac McCall constructs brooches of bronze, silver and gold; for these, he uses images from the subconscious, from the petroglyphs of pre-history the breastplates of Roman legionnaires and trophies carried through the streets of Rome. This imagery is overlaid with an aura of the West: nature, western ranches and the radical humor of the San Francisco Bay Area.

McCall describes his sources as "highly eclectic." Like Joseph Cornell, he accumulates what he calls "a lot of stuff," "It's like opening a drawer," he says," and finding things to pull out. They all mean something and they're all important, but the effort to connect pieces is sometimes difficult and tenuous." While living most of his life in the West, he speaks of an incongruous and influential childhood experience in Japan. In this foreign environment, he was receptive to everything - Japanese fairy tales, the colors and textures of everyday objects, a favorite samurai doll holding miniature swords. As an adult, McCall continues to find excitement and visual information in the overlapping patterns of Japanese woodblock prints, ceramics, in metal weaponry and the humbler household utensils.

The textured metal used by McCall for a brooch titled Blue Moonlight recalls the fabrics of traditional Japanese kimonos. A piece of shaped slate, with color airbrushed on the surface, serves as a foil for the controlled metal patterns, while sharing a kinship with the stone gardens of Japan. In the foreground of the brooch, a window acts as a framing device. It follows the format adopted by McCall in order to maintain a sense of continuity from one series of brooches to another. The frame suggests the Japanese shoji screen that is pushed aside to invite the interpenetration of inside and outside space. To McCall, the rectilinear openings in his work are viewed as "little metaphors," that is, "windows of opportunity" and, conversely, in the jargon of the Pentagon, "windows of vulnerability." Vulnerability is emphasized in Blue Moonlight by a pointed sword that penetrates the rock and the open window. The weapon, whether consciously or not, strikes a bond with the forged swords that for centuries were associated with the Japanese Shogun Age.

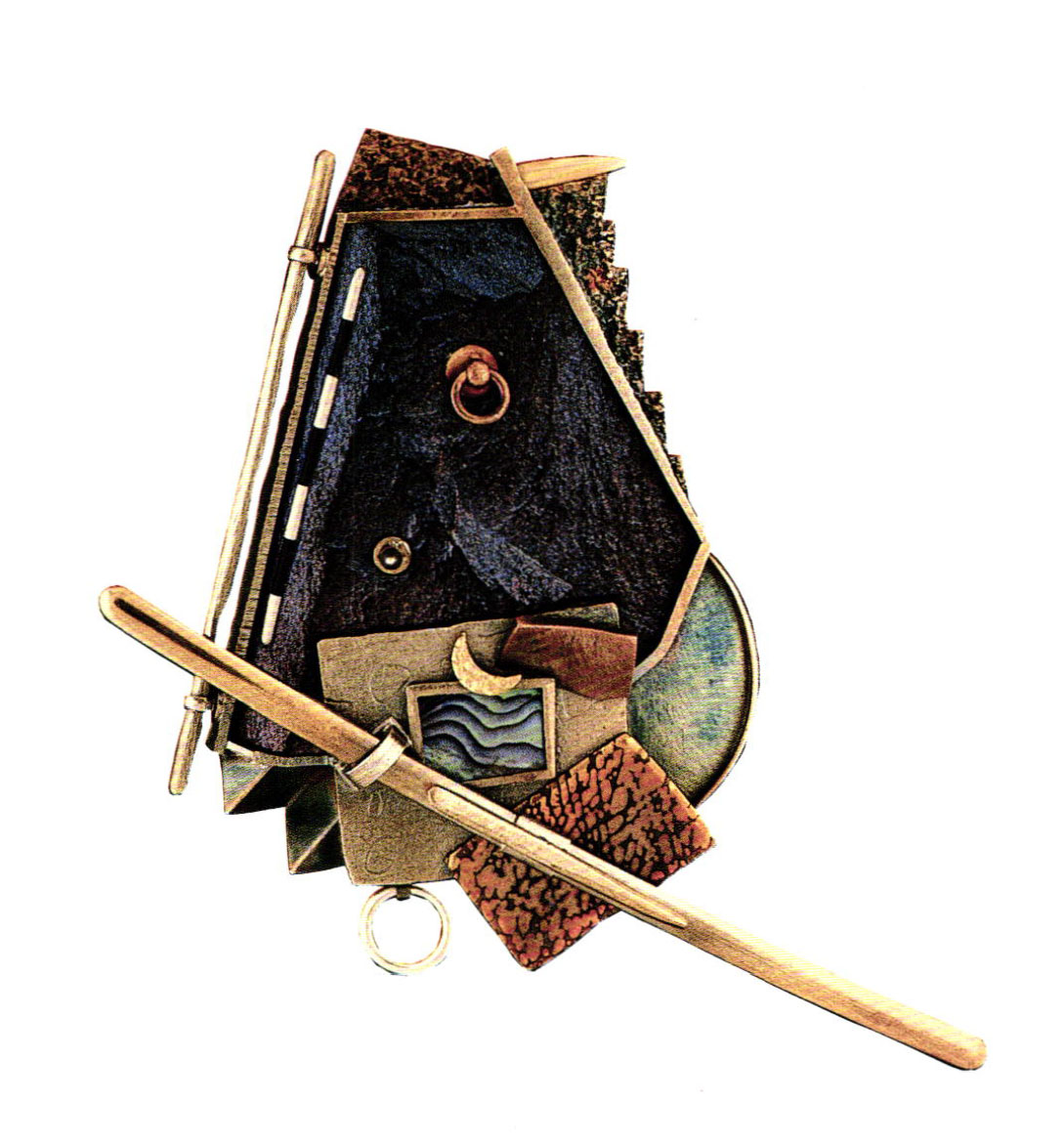

Riot Gear is also about weapons - clubs and rings clank against a shield similar in shape to those carried by phalanx of Korean police. McCall hastens to make it clear that the brooch does not contain a political agenda. He says, "I've always been interested in armor and military images, but I'm not a gun man. I don't keep guns; but they interest me as pieces of metalwork." The slate body of Riot Gear is topped with a metal band textured like leopard spots. The leopart skin motif is used as an accent in many of the brooches. It has for McCall a primitive impact that is mysterious and exotic. It is also associated with camouflage. Intrigued with this form of military disguise, the artist's attention was attracted to a book on methods for concealing jet aircraft. Among the illustrations were planes owned by small African countries. Some of these were painted with designs resembling native insignia or shields covered with animal skins. Riot Gear itself is like a chameleon. The imagery of the shield at times seems to disappear and dissolve into the helmeted head of an Aztec Jaguar Knight.

The helmets of Pre-Columbian warriors, Celtic pins for woolen cloaks, medieval shields decorated with heraldic devices and armored breastplates all form prototypes for McCall's brooches. Originally his pieces were flat; he discovered, however, that doming made the brooches look more assertive as well as strengthening them.

"(A Brooch) carries a certain authority, that seems to me, different from other adornment. A number of people in our culture who don't wear jewelry do wear badges, usually, signifying some position of authority. Most jewelry forms speak about style, fashion and/or wealth, which brooches, usually, do the same. The seem to carry a certain added authority because of how they are worn. It is that somewhat subversive quality that I like."

The "subversive" element in McCall's art involves layered meanings and alternative solutions. A wizard of ambiguity he says that he is drawn to those situations where truth and fact are not necessarily the same thing. He likes the idea "that someone who may not be interested in jewelry as an art may have to deal with a piece because it suggests, if only for a moment, some sort of emblem which indicates a connection to the world beyond the esthetics of the expected."

McCall creates puzzles for the intellect and for the intuition. Asked about the meaning of the "x" that is a current symbol in the brooches, the answer is, "It's a shape I like; shapes develop subliminally. For me, it is a cliché associated with the seventies: the spiral, which goes back to the Bronze Age, is the cliché for the eighties." He says, "I'm intrigued with clichés. An image begins to lose power when it becomes so much a cliché that it no longer means anything. At the same time, the image gains power because people have begun to identify with it and learn from it. I have become seduced by clichés. I think a lot about this."

It is common knowledge, McCall points out, if "xs" and spirals and stars appear on the pages of a comic book in a balloon over a cartoon character's head, they are symbols for profanity. In Montana, he continues, there are ranch gates with wrought iron initials or brands across the top. If spirals and stars and "xs" were marched over the archway, they would look familiar, but the real information would be different from the observer's expectations. Jewelry can be subversive in this ambiguous fashion. A "relatively traditional format and materials" allow the brooches "to carry imagery that might not be expected."

Unexpected signs and symbols are a part of Big Ranch. In this piece, the window as frame has been replaced by a gate. Security and danger coexist. The slate ranch house seems to offer safety but threatening forces wait outside. A human skull is mounted on a gate post, a grim reminder of frontier justice and a grimmer reminder of the cliché that has become synonomous with Santa Fe decor - the ubiquitous cow skull. In front of the house, a spiral is balanced on a classical column, implying a tongue-in-cheek reference to Post-Modern architecture. The spiral becomes more ominous in the figure of a snake coiled close to the doorstep. "I sometimes think in terms of images of snakes and knives," McCall remarks. "They suggest that there's still an element of melodrama that persists in the West. Part of this feeling comes from living in an urban area that has many problems. All of the violent symbols of the Old West are now found in the cities."

Despite the richness and diversity brought together in McCall's metalwork, the whole is taut and controlled; the pieces are assembled without sacrificing precision of technique or function. McCall admits that he likes high tech. "l love the clean, spare look," he says, "but at the same time I'm drawn to the immediacy and directness of folk art and vernacular expressions." Personally, he prefers to work with traditional materials. He does not experiment with titanium or anodized aluminums; he is quick to admit that beautiful work is done with new materials and techniques. For his part, McCall finds how titanium is used in submarines more interesting. Using silver, gold and bronze, the brooches are often enlivened with small stones that have the effect of small points of light. McCall feels that when expensive, faceted stones are used, a line is crossed and the work begins to be about intrinsic values of the materials. The metal surfaces are important to McCall. He says that he uses "a lot of roller printing" and lately he has been casting sheers of textures. The patterned surfaces are reminiscent of natural or geological textures. McCall adds, "I'm fascinated by the way materials and objects - particularly metal - age through time and use. I attempt to develop surfaces and patinas that both suggest a sense of history and anticipate further wear."

As masterly symbols and metaphors, Mac McCall's visual signs have gathered strength through repetition while always leaving a last mystery unrevealed. The message is that things are not always what they seem. The artist says, "I know what a little skull means to me, but that's not the point. I know what I mean; what does my work mean to you when you look at it? I know what I feel. What do you feel? I know what I know about this. What do you know about it? What do you bring to the experience? A person may come back and say, 'Gee, that's what I see; this is interesting.' In this way an artist may learn something about himself."

Elizabeth Skidmore Sasser is a Professor of Architecture at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX and a contributing editor to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.