Martha Glowacki & Fields of Reference

10 Minute Read

Martha Glowacki's works are sculptural abstractions on the theme of landscape. They demonstrate her interest in the imposition of order on the randomness of nature and her discovery of pattern, both natural and manmade, in the landscape. The pattern may come from the systematizing of maps or from the geometric traces of human activities and structures. These may be archaeological remnants of ancient settlements, still out. lined through chemical deposits left in the soil by the stone of archaic buildings, or they may be more modern remnants, such as wobbling fences and decrepit farm equipment.

The pattern in landscape is made apparent through the geometry of map notations. Maps are landscapes in code, landscapes for fact and for imagination. Patterns may be long-term, as in topography, or they may be transitory, as in the linear pattern of a plowed field. These are all ways that living beings relate to the landscape, putting marks on the earth, taking from the earth, and ultimately returning again to oneness with the earth.

Time is a pregnant participant in Glowacki's works. They seem to reflect a peaceful submission to natural processes. In each case, the images reflect an act—whether the construction of a fish drying rack, the assembly of a fencerow or the collection of twigs and fibers made by birds or by wind. But in every image, the act is long past. The works suggest an easy serenity; those acts are mere specks in time, but suggest their own eternity in their repetition. These are small acts in the millenia that lose their individuality in the seamlessness of time, a continuum Glowacki evokes in coupling the antiquity of symbols drawn in caves with the modernity of photoetching. Her ease in making these connections may come from personal experience. She worked once at a historical society, cataloging agricultural implements, 19th-century household goods and clothing. Some of her specific images may derive from that.

Glowacki uses mostly nonprecious materials, particularly copper and bronze. The colors suit her landscape theme, and these materials keep the intellectual value of her theme from becoming precious. And these are intellectual works. They are not literal. Even her photographic imagery is not specific. Instead, she uses the textural impressions drawn from photographs of grasses and fields to convey the abstraction of an impression. Map markings are another abstraction, with nature seen through the filter of humanity's need for order and information. The map is nature intellectualized. Another layer of reality is provided by the three-dimensional elements, most often fences and stands of tall grasses, but also hogans or arbors or other forms.

All these are presented on shifting fields (both meanings intended) of reference. In most cases, some horizontal element represents the earth itself, the rolling contours of southern Wisconsin. The land is open, empty, windswept, but like a winter field or burned-over ground it is not barren, but waiting. The earth surface is not massive, heavy or stable.

Glowacki avoids that kind of firmness by propping these landscapes up on stilts, by cutting edges askew, by splitting the earth image and bending it apart: in every way possible, she keeps this earth base up off the real base of the pedestal. This gives it a visual lightness that contributes to her meaning. The earth is not then a static anchor, but a sensitive skin upon which events takes place. The earth surface is like a magic carpet, an elusive image, shifting through time and space.

These images are not just elusive, but surprisingly illusive. Unlike more traditional large-scale or figural sculpture, they do not deal with volume or mass. They remain sculptural because they define space in the same sense that contemporary large-scale sculpture does, yet monumental sculpture—say, Mark di Suvero's, or Loren Madsen's, or Linda Howard's—retains a tangibility that Glowacki is somehow able to escape. I suspect the key is her metalsmith's concern with surface. The craft tradition of attention to form and surface allows her to deal with both object and image (illusion). She has a dual means of expression.

Thus that magic carpet surface of earth in Split Field on Stilts or Three Bound Fields, for example, not only suggests a physical dimension of the rolling earth, depicted three-dimensionally and tangibly, but Glowacki can add to that the sense that this little fragment of surface extends into the whole surface of the earth, binding our globe together. There is a hint of the kind of space achieved in Chinese painting: one has the impression that space is endless, and that Glowacki has chosen to depict this little segment because it is all that's necessary to suggest the larger whole. No picture frame is necessary, as in Western painting, to put an ordered framework on this conception. It could be a slice of life or a slice of dream.

Glowacki herself attributes it to a more mundane cause: catching glimpses of the scenery as she drives past, a natural fragmentation of image resulting from the speed of contemporary transportation. It exists in image to draw us into the world that it defines for itself, half-hidden, half-known, half-imagined, that has little to do with the literal concreteness of traditional large-scale sculpture. The scale contributes to the achievement by requiring the imaginative leap on the part of the viewer. It is neither real scale nor daunting, aggressive monumental scale. It is a vision of shifting space that can be entered and explored only by the imagination. Surely this is the finest kind of experience that art can achieve. It has no limits.

Not all the pieces in the exhibit achieve this negation of boundaries, but it's surprising how many do. Particularly interesting is that Glowacki achieves this end in two pins, functional works. I suppose there's some question as to whether that's a good thing in jewelry. Glowacki has in the past made quite a bit of jewelry, some in brass, copper and bronze, some in handmade paper marked with stitches and encased in plexiglass. They were quite abstract, she says, like small-scale paintings. She was chagrined to find that they wouldn't sell for that reason—if they appealed as paintings the public wanted them on walls, not on the body. Perhaps the pins in this exhibit, Field Sight (Blue Crass) and Field Sight (Green Grass), would suffer the same fate and would never be worn.

Three Bound Fields, Sculpture, 1982. Photoetched copper, bronze, and paint, 21 x 13 x 5″

But in jewelry scale, 3 x 3½ x 1 inches, they achieve that same shifting of space, time and reality. The etched surface of illusive grass is augmented by a swath of three-dimensional grass, the wiry, harsh, brittle grass of winter. Remnants of fence cross the field, a manmade feature alike in linearity, projection and tactility to the natural features. Glowacki has constructed the parts with a slight flattening of three-dimensionality and with a swelling two-dimensionality, so the images don't seem to settle into one plane of space, but rather to bend and shift as if one were looking through shattered glass. The shifting averts any danger of this rural scene collapsing into cute miniaturization. One has the sense of two realities meeting, but not exactly, like those children's pins in which a change in the viewer's position makes the image move. These pins hover right on the edge of such a shift, with simultaneous realities.

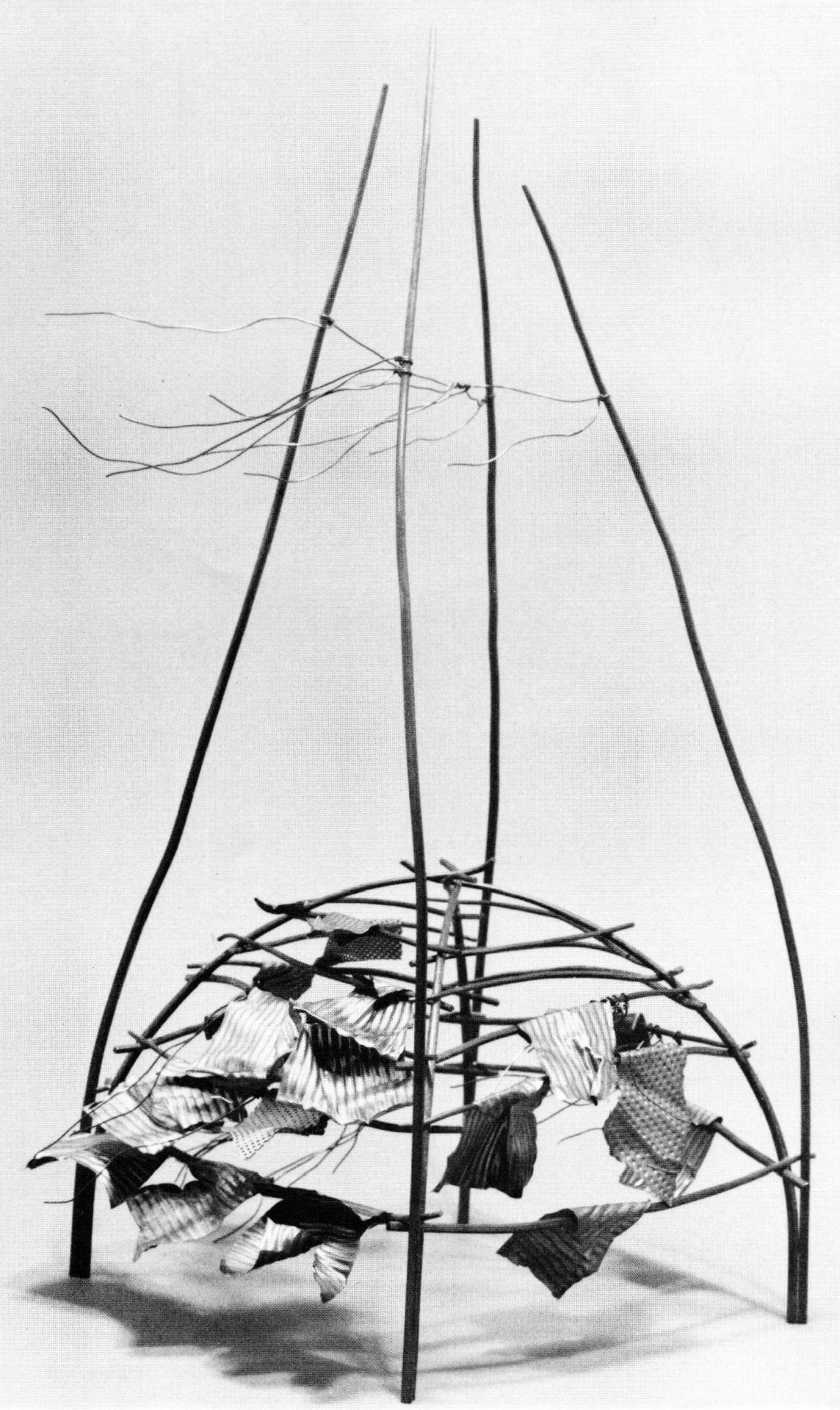

Four Corners Wind Dome and Big Wind Dome are heavy wire structures that do not rely upon the earth surface plane for their visual base. Both suggest Indian drying racks or hogans or corncribs on which tatters, represented by bits of copper sheets, have appended themselves—perhaps caught by the structure in the wind, or torn from the structure by the wind. Some of these bits are found metal; others are put through a rolling mill. Their patterns are bent, wrapped, frozen now but recalling fluid flapping in the wind.

The dome itself is a spiral, mimicking the natural form of a dust devil. The spareness of the wire outline keeps these works in the realm of suggestiveness and imagination. Yet they do not shift through space. They are objects—fixed, settled, acted upon.

Split Field on Stilts, Sculpture, 1982. Photoetched bronze, copper, brass, and paint, 14 x 9 x 7″

A similar structure that exceeds that limitation is Shard Series: Heron Arbor. While this structure may be decayed, it may also be a chance occurrence of limbs in a thicket, a protective configuration in any case. An undulating sheet of copper floats midway through the arbor, etched in river blue. Imprinted in the sand or mud is the track of the heron. This has personal meaning for Glowacki. Her parents are devoted bird watchers, and she did discover and photograph the mark of the heron along the Wisconsin River. Yet one does not need to know this. The track seems to glisten in the grainy blue of the shifting surface like a talisman of some significant presence, and the surface is once again the viewer's entry into an imaginable whole reality, the world of the riverbank, far from the complexity and rush of civilization.

Shard Series: Falling Bundles is a less specific representation. It, too, consists of a framework and a landscape layer, this one leaning downward from the center, beyond the confines of the structure. The framework is again twig like, seemingly accidental. Some twigs lie on the surface of the protruding copper sheet, which is embellished with a photoetching of twig marks in a shallow, sandy stream. One sees the surface of the sheet as the surface of the water, and the ghost image of submerged twigs as below, beyond. This concept is comparable to Monet's waterlillies, where the canvas surface is equated with the water's surface. In this case, the abstraction of reality through photoetching, which alters the nature of the image, gives an even broader spatial concept. The surface seems to vanish, and one glimpses a time sequence of the erect limbs of the framework breaking and falling and disappearing in vast space, in an infinite beyond.

Field Sight (Blue Grass), Brooch, 1982. Photoetched bronze, brass, copper, and paint, 3 x 3½ x 1″

Shard Series: Ring Marks is a wall piece with which Glowacki is not entirely at ease. It may not be completely resolved, but it has interest even in its present state. The framework is roughly snowshoe or shield shape, and two copper sheets, tied on with wire, span it near the maximum width. One rod of the framework crosses over the front of the sheets. The piece is more relief than sculpture. Focus is on the enameled surfaces, which are mottled and scarred like an architectural site seen in an aerial photo, a theme Glowacki has favored for several years. But that's not all. There's a reminder of cave painting in the several spirals which mark it. Among the most ancient of man's markings, these are also natural forms. And they are celestial forms, hinting of the starry infinity. Furthermore, these marks suggest modernist painting inspired by ancient art, from the works of Picasso and Miro through Abstract Expressionism. Because one image does not predominate, the piece is perhaps unfocused. But it's still provocative.

She maintains a studio and teaches part time at several local schools. Her early graduate work was functional, and she returns to pins occasionally, but the drift has been toward sculpture and larger scale work. She has moved from jewelry scale to as much as 21 inches in multipart works. Like Richard Helzer, she is interested in maps and markings, and a few pieces even refer to ancient English structures. There is also an affinity between her work and the mysterious. Emotionally introspective objects of Carol Kumata, a fellow MFA from Wisconsin and, coincidentally, a friend. Kumata's work tends toward poetry and mystical transformations; Glowacki's landscapes, by contrast, are allied more appropriately with prose, with the simple directness of the midwestern fields and the steadiness of mid-American common sense. The transformations in her work find their magic in tiny increments, in the endless seconds of passing decades and the numberless rolling hills and blades of grass of the Midwest. Glowacki's value is akin to that of the craft tradition: care, control, attention to subtlety, coupled with a meaning that transcends the particular of her personal perceptions and achieves a universal.

Martha Glowacki's work was shown in a solo exhibit at the Kit Basquin Gallery in Milwaukee in December, 1982

Janet Koplos is crafts editor for the New Art Examiner, Chicago, Washington, D. C.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.