Mary Ann Scherr

14 Minute Read

Machines have always fascinated Mary Ann Scherr - first the drill press, bandsaw and oxyacetylene torch, and now the computer; Autocad, Deluxe Paint and PageMaker. For her, the computer represents one more opportunity to incorporate the latest technical advances into good design. It is part of that never-ending quest to make the quintessential human adornment.

Jewelry is not just fashion or fad for Mary Ann Scherr, it is a way of life. As jeweler, teacher and pioneer in methods for working with exotic metals, her contributions to the jewelry industry span 30 years. And her research and development of Fashion jewelry to disguise lifesaving devices has been recognized worldwide, including body monitors, etching on metal, pioneering the use of nontraditional materials such as stainless steel, aluminum, plastic and titanium, and in 1989, the development of a new technique to accelerate and improve the etching process.

In addition to her studio work, she was associate professor and director of the Metals Program at Kent State University and taught design at the University of Akron and the Akron Art Institute. In 1968, she began teaching in the summer program at Penland School. When she moved to New York, she joined the faculty at Parsons School of Design, and, in 1980, became chair of the Department of Clay, Metal, Glass and Textiles. Now she lives in Raleigh, North Carolina, and teaches weekly studio courses in jewelry design at Duke University.

Scherr's career began in junior high with portraits on bottle corks. A local department store paid her $20 for them and with the money she bought huge quantities of butcher paper to use for drawing.

In 1950, she married Sam Scherr, a fellow student at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and they left for design jobs in Detroit, she to Ford and he to General Motors. She was one of the first female automobile designers in the industry and worked on interior and exterior designs for Ford, Mercury and Lincoln. Hood ornaments, hubcaps, door escutcheon panels, instrument panels and color selections were second nature to a woman who looks like she wouldn't know the front end of a car from its rear.

After a year-and-a-half in the automobile world, she and her husband decided to start their own industrial design company. Her first designs were children's books, which she wrote and illustrated. Her painting skills led her from coloring books to restaurant murals. As the company began to move into product design, she turned to ceramic cookie jars, which she designed and sculpted using nursery-rhyme themes. They sold for $3 each. Twenty years later they gained national attention when North American Watch Company paid $19,000 per jar at an auction of Andy Warhol's household goods.

The first baby put a hold on her active participation in the design company, but six weeks after Randy was born, she was enrolled in a jewelry design course. Feeling the metal in her hands was addictive. "I knew this was special," she said. Two nights into the course, Randy became ill and she had to drop out. Undaunted, she built a workbench at home and began to teach herself about metals. She remembers those exasperating years when she used hard solder on everything.

It wasn't long before her inventive mind began to think about improving the method for illustrating on metal. In 1950, through extensive experimentation with combinations of chemicals and information from local chemists about toxic effects, she began to etch designs on metal. It wasn't too many years before she was recognized as a leading authority on jewelry etching. Ultimate confirmation of her expertise came when Oppi Untracht asked her to be his technical advisor on etching in his definitive jewelry encyclopedia, published in 1983.

In 1954, she started thinking about clothing, believing that men must be designing maternity clothes because they were never comfortable. She designed one that was flexible using an "A" line that freely expanded as the mother needed it. She sold that "one piece" maternity dress, which became a standard, to Stern Manufacturing Company. Lord and Taylor suggested that she go into the fashion business, but by then she was in love with metal.

It was during this time that she and her husband went to Korea at the invitation of the United States-Korean program, "Aid to International Development." His company researched and developed Korean products to be sold in international markets.

While there, she taught metals techniques and developed a collection of jewelry based on ancient Chinese-Korean charms. She sold her designs to Brentano's and they marketed them throughout the United States. They became the first in a series of museum replicas that today are sold all over. The prototypes were cast from steel molds made in the United States and then given to the Korean "cottage industry" to produce. During this period, the plastics division of General Rubber Company, Akron, Ohio, worked with Scherr on methods for laminating fabric and encasing it in plastic. The result was a perfect match for a couturier collection.

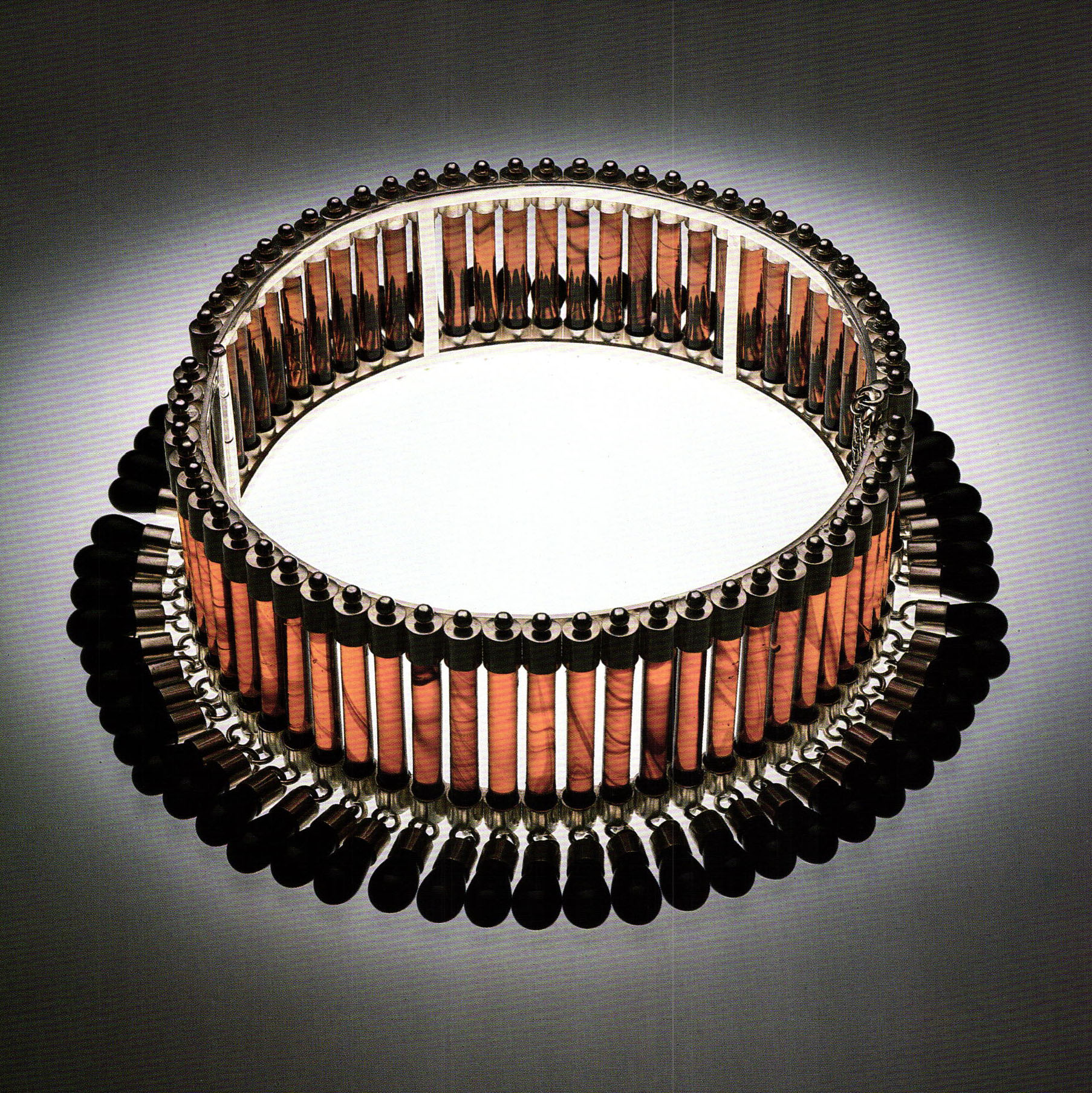

In 1960 she was invited to exhibit her jewelry at an Industrial Design Society of America conference at Greenbrier, Vest Virginia. An executive from U.S. Steel approached her with the idea of designing jewelry out of stainless steel as a novel way for the company to exploit other uses for stainless, as well as another way to lobby the U.S. Congress that stainless steel would be the perfect new metal for coinage. In the end, stainless lost to the copper sandwich, but Scherr's collection of 26 pieces toured the country, ending in a solo exhibition at New York's American Craft Museum.

Working with stainless requires months of experimentation, especially with forcing oxides onto a surface that is created to resist contamination. Ultimately, she realized surfaces in gray, orange, black and white patinas. She developed delicate welding processes to attach pieces of stainless to each other, increasing her own knowledge of metal techniques. One of the most challenging pieces of the collection was a necklace with interlocking elements that looked like a small wall of pierced decorative parts.

When Penland School invited her to North Carolina's Blue Ridge mountains to teach metals and jewelry design, it was a turning point in her career. In an atmosphere of interdisciplinary cooperation, teaching students who are willing to commit to intensive concentration is so heady that 22 years later she is still participating.

On the first day of one of Penland's new sessions, as she was greeting a returning student, the student's scarf fell off, revealing a trachea tube in her throat. She had undergone radical surgery and the tube had been inserted permanently. Scherr offered to make her a piece of jewelry to wear at her throat. The one-by-two-inch cover of gold and silver, with precious stones, lay over a standard-issue trach and helped her friend regain a new sense of personal worth. Ultimately, a copy was invited into the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

In the meantime, the Mayor of Akron asked her to design a costume for Ohio's Miss Universe candidate. The theme was to be space, since Ohio was the home of all the first astronauts. "They were going to walk on the moon that night," Scherr explains, "and while I watched television I was working on the costume. I had decided to simulate a heart monitor device into the belt, and as I worked I watched the heartbeat graph on one of the astronauts."

That began the most fantastic and frustrating time of her life. She started thinking about her student with the trach and others who would like to cover malformations or to disguise the holes in the human anatomy surgeons must make sometimes to save lives, as well as those who carry monitors to warn them about heart complications. If she could make jewelry to disguise these life-saving devices, she could help many people adjust. The trach neckpiece was a start, but she knew that what she wanted to do would require engineering expertise. Harry Hosterman was the first biomechanical engineer to help her and, with him, she designed and patented a bracelet that masked a pulse monitor. After that came a jeweled pendant that converted into an oxygen mask.

As each monitor concept took shape, she had to figure out what was needed and then locate the engineering talents to help her with the working components. A case in point is her relationship with Kent State Biology Department and its work in air pollution. Their pollution monitors needed as much as a 14-square-foot wall, and she wanted to reduce that to five inches. She was alter a device that would alert heart patients and asthmatics to dangerous levels of smoke and air pollution. The researchers laughed at the idea, but a few months later Hosterman called and said he thought it could be done. Another pollution device in the shape of a pendant operates like a music box, and, when activated by smoke in the air, plays "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes." That design uses an electronic system, which was one of the first examples of electronically induced musical notes.

In 1970, the Liquid Crystals Institute at Kent State University was involved in primary substance research under Professor James Ferguson. For Scherr, liquid crystals were the answer to devices that could help detect carbon monoxide, ultraviolet radiation and thermal body/air conditions. Using the crystals, she designed a portable electrocardiogram necklace, which the American Medical Association documented on film. There, for the first rime in medical history, the heartbeat pattern was seen in full-color, helical display.

Other inventions were the "No-Nod" device that buzzes when the head falls forward in sleep, a necklace that doubles as a neck brace, sterling-silver rings with magnifying glasses attached and flexible rings that will accommodate swollen and enlarged knuckles. When she injured her own finger in a studio accident, she created a "Thumble" that began a series of cosmetic coverups in silver or gold for people missing parts of fingers.

Scherr created metal sculptures for the Aluminum Company of America, promoting their institutional theme "Rediscover Aluminum." She designed and sculpted four mythological 12-inch figures, using a then new "shell lost-wax" casting technique and caught the attention of leading national magazines.

From 1968 until she moved to New York in 1977, Scherr's Ohio studio of seven artisans produced products, commissions and limited-production jewelry in exotic and precious metals.

It was when she and Dr. Steve Kanor, a biomedical cancer researcher, developed a sensor system to monitor a baby prone to SID, or "crib death syndrome," that she came lace to lace with the complications of federal drug laws. As a result, this monitor remains on the drawing board.

One day she received a call from Dr. George Malindzak, Jr., Director of Medicine at the Medical School at Northeast Ohio Universities. He had recently come from North Carolina and the Environmental Protection Agency where, among other things, he had been working on body monitors. He found out about her work and asked her to join him in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he would deliver a paper on body monitors to the International Conference of Station and Body Monitors. Her monitors were the only working ones in the world and Malindzak wanted her along to demonstrate them. This gave Scherr exposure to the professional biomedical world, and, ultimately, the popular press. Again she was the subject of articles in periodicals like The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Time, People Magazine, Omni and even the children's newspaper The Weekly Reader. She made appearances on the Today Show, Good Morning America, Johnny Carson and Dan Rather's nightly news. French, Canadian, English and Japanese television interviewed her via telephone and video tape.

With Malindzak, she designed a breath monitor. In this device, a sensor responds to the breath and electronically activates a light-emitting-diode display of green through yellow to red. The quantity of breath hydrocarbons causes a movement of light and determines the quality of breath odor.

Over a period of 10 years, Scherr worked sporadically on the body monitors, consulting with engineering experts and experimenting with gold, silver and stainless steel. Interest would ebb and flow cyclically. Because of her research, The Defiance College in Ohio awarded her an honorary Doctor of Humanities. By this time, she had invested over $150,000 of personal money into a dozen prototypes and realized that major money was needed to do more sophisticated engineering and to test the feasibility of manufacturing these monitors. Until outside interest in funding could be found, the inventions went on the shelf.

When Scherr moved south, she renewed her friendship with Malindzak, now working for the National Institute of Health. With his help she reestablished the medical base for the monitors, which resulted in an exhibition of the monitors at the Duke University Medical Center. Another exhibit is scheduled for Raleigh's Rex Hospital in the Spring. Today, of course, the prototypes, which still work, are outsized. In the 15 years that have passed, new technology and the use of the microchip have reduced the size of the monitors, thus requiring smaller, more delicate products. Even so, the conceptual function continues to challenge the industry.

Although the body monitors almost consumed her, they were only part of Scherr's busy life. Early in the 1970s, she was invited to be a part of the Reed and Barton "Signatures 5" show with metal artists Arline Fisch, Linda Watson-Abbott, Ronald Pearson and Glenda Arentzen. She also experimented in developing photochemical piercing and inlay, which resulted in fully etched-metal patterns of gold inlay on silver. At this time too, she became one of the first Americans, and one of the few women, to become an associate member of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths at Goldsmiths Hall in London. This came about after she presented her work, along with William Harper, Heikki Seppä and Mary Lee Hu, at Goldsmiths Hall.

While in London she was introduced to titanium, a new material whose color could be changed through electrically charged water. She invited James Ward and Edward De Large to demonstrate the process in New York for her at Parsons. After that demonstration, she bought the power equipment necessary to anodize titanium and created a collection that she exhibited at the FAE (Fashion Accessories Exposition) in New York. Interest was so great that she and her husband started American Titanium, manufacturing 200 pieces a day for distribution worldwide. In the process of fabricating the necklaces, earrings, bracelets and hair ornaments, she discovered that a dental material "No-San" could replace the dangerous hydrofluoric acid needed to develop the purity of color. Titanium jewelry was introduced at Robert Lee Morris's New York Artwear Gallery in a show that included Morris and 10 others.

Etching on metal has been an inrerest of Scherr's since those early days when she was trying to teach herself about materials. In 1988, she attended the Society of North American Goldsmiths Conference in San Antonio, Texas, where the Rio Grande Company of Albuquerque demonstrated a graphics color printer. Fascinated by the possibilities, Scherr printed an ink image on a piece of scrap metal, returned home and began to investigate the potential of "instant" silkscreen printing on metal. It took two years to perfect the process, which begins with an art image copied by a standard paper-copy machine. Then, using the Rio Grande printer, an "instant" silkscreen image is transferred to a metal surface. After curing, using a nontoxic water-based resist, the metal is etched. The new, revised method replaces much of the equipment and time-intensive systems used to reproduce images on metal surfaces. What had required two to five days is accomplished now in a matter of hours. From the most delicate design to bold, hard edge, multiples can be etched with perfect integrity. Scherr has already done a number of workshops on the procedure and spends hours on the phone explaining to designers around the country how the process works.

When Scherr philosophizes about her work, her words are those of a dreamer, not a commercial jewelry designer. "For me art is not just the action of the maker, it is the investigation, the learning, the change, the discovery. It is exciting to watch a surface break into life, whether from a difficult computer exercise or just pressing a switch, which starts the electricity, or simply sketching an image. I am deeply moved when a finished work of mine is worn and appreciated, but the greatest satisfaction, for me, is when I can make those small beginning thoughts become a full expression."

Note

The information in this article comes from many hours of conversation between Mary Ann Scherr and the author during October and November, 1990.

Blue Greenberg is an instructor of art history at Meredith College, Raleigh, NC and a regular art critic for the Durham Herald.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.