Master Metalsmith Irena Brynner

15 Minute Read

The following text is edited from two interviews taped in 1982 with Irena Brynner, one by Dorothy Van Arsdale in Florida and one with Julie Schneider, a graduate student from Tyler, in New York City.

I was born in Russia and lived there until I was 11 years old. Then I went to Manchuria, finished high school and was sent to Switzerland to study art at the university. At the end of 1939 I returned to Manchuria, which I considered at that time my home, and continued working mainly in painting with private tutors. In 1944 we were forced out of Manchuria by the Japanese, because my father, who had died in 1942, had represented British and American interests in China during the war, and they decided he had been a spy. We left for Peking where we stayed until 1946, when we moved to San Francisco. There I worked for two years intensively on sculpture in clay and stone.

Since we had left behind everything we owned in China, I had to begin to consider how I would earn my living. I had been rather spoiled until then. I tried giving sculpture lessons in three different Catholic schools, because they were private schools and I had no teaching credentials. But the schools had practically no facilities nor tools. I was earning so little and had such difficulties that I started seriously thinking about doing something besides sculpture. I had painted portraits, so I could have chosen to be a society portraitist and probably earn a very good living, but it did not appeal to me. So I started looking in the crafts. At first I thought the natural craft for me would be pottery, since I had worked with clay, but very quickly I felt much too restricted by the vessel form. By chance at this time I saw a contemporary piece of jewelry by Clair Falkenstein which fascinated me because it was so much like sculpture. I felt here, finally, was an area where I wouldn't have to compromise. I would make sculpture in relation to the human body instead of sculpture in relation to space or in relation to architecture.

I could not afford to take jewelry making lessons, so I started working with Carolyn Rosine as an apprentice. I worked with her for two months in the mornings and taught in the afternoons. Working for her involved much tedious sawing out and polishing which did not teach me anything. And then before Christmas I was introduced to Franz Bergman, a jeweler and ceramist who needed help making his jewelry orders while he was doing ceramics. I began to work for him and he showed me step-by-step the whole process. He worked next door on his ceramics and left me to do the entire jewelry piece. He paid me half of what he would get for his things, which was also very rewarding. This contact with him taught me a lot and enriched my contact with jewelry. Although I worked only 12 hours with him two or three weeks before Christmas, this was a true apprenticeship.

Iren Brynner's book, Jewelry as an Art Form, was published by Van Nostrand Reinhold in 1979.

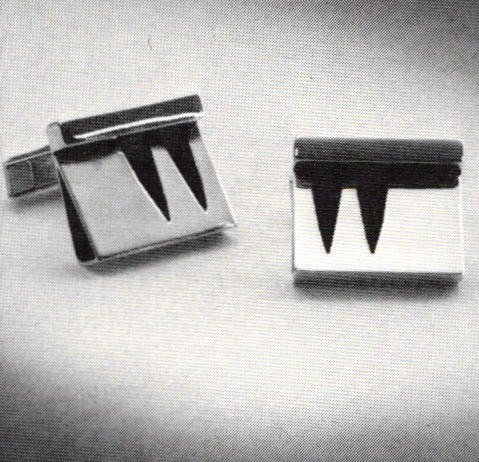

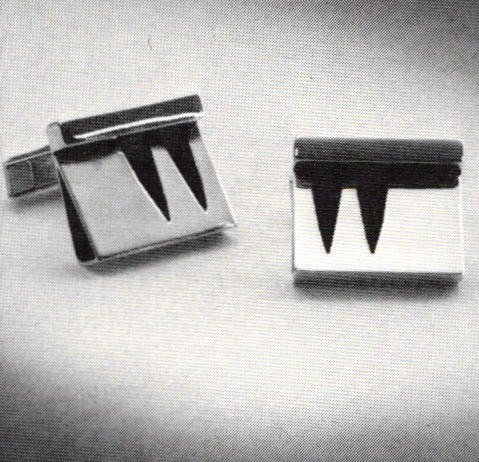

After that I went to Adult Education classes to learn more about the practical side of buying materials and tools and I started working at home in a very primitive way. A Bunsen burner was my soldering equipment and I used an ironing board to solder on. In this way I started learning, really by trial and error. I started working by myself in January of 1950 and in March I went to Casper's, one of the swankiest gift shops in San Francisco. I took my first cufflinks and pin to the manager Bob Hight and told him I had worked for Mr. Bergman. I said I had made jewelry previously as a hobby and that now I wanted to sell my pieces. Would he be interested? After looking over the work, he told me that my pin was horrible but that the cufflinks were very nice and if I had any more could I bring them in. I quickly said, sure, sure, and rushed home to make some more. Another shop, Nany's, helped many, many craftsmen; they started taking my things and then Fraser started taking things. Although it wasn't easy, I began to earn a bit of a living this way.

I was really self-taught in jewelry. As I could afford better tools and equipment I learned their capabilities. I think that my work differs from that of American and European craftsmen because I had no traditional background. If I wanted to use a stone, I had to invent how to set it.

In San Francisco, there was an open-air art show every year, subsidized by the city. It was open to all craftsmen. Through this show, I started to have contacts with different jewelers. I met Merry Renk and Margaret DePatta, who was a leading force in the metal community. There was also Byron Wilson and an Italian jeweler, Peter Maccarini. We became concerned about the quality of work at those open-air art shows and started thinking about forming an organization to promote professional standards and metalsmithing education. In this way the Metal Arts Guild was founded with a small group of about eight to 10 people. By 1951 we had started to hold serious meetings and make up by-laws.

This group was marvelous because of the guidance of Margaret DePatta. Her husband, Eugene Bielawski, was also a metalsmith, and they both were trained in Bauhaus methods at Moholy-Nagy's School of Design in Chicago. It was they who guided us in all our efforts. However, our discussions were lively, as we did not always agree on the purpose of jewelrymaking. With her Bauhaus background, DePatta believed that every design you made should be justifiable, practically mathematical, logical as opposed to emotional. I, on the other hand, work very spontaneously, very emotionally with no anticipation. I acquired techniques as I went along. I remember, for example, that it was a fantastic experience for me the first time I hammered a gold wire flat. All of a sudden I discovered that it was a spring. I bent it and immediately realized I could make necklaces that sprang open instead of having a catch. However, like Margaret DePatta, I was at first very influenced by modern architecture. My things were all very geometric and stark. I had a very close friend who was an architect and I think that had something to do with it also. The first technique I acquired was constructed jewelry, which lends itself to a tailored style.

As I went along, I started discovering new techniques. Classes in holloware given by the Metal Arts Guild were particularly useful, as they taught me about the stretching properties of metal. My work started to have more curved surfaces, and little by little it became softer, more three-dimensional.

Five years after I started working in jewelry, in 1955, I started teaching adult education classes, three nights a week, which as it turned out taught me a lot. I remember at the first class an elderly man brought in an awful ring. I began to criticize: this is bad and that is bad, when all of a sudden the man said, "I'm mighty proud of this ring. It's my first ring." All the words got stuck in my mouth and I said, "Yes, it is very nice, but I am sure that the next one will be much better." This started to teach me about relationships with my pupils. In those classes I really learned a lot about technique because I had to think fast and solve so many different problems, not just my own problems. I think I had classes that varied from 14 to 36 people, but I tried to teach each person individually. I will always cherish that experience because I found through teaching that each individual has the potential and a tremendous desire to create something. And only shyness or insecurity keeps them from pouring out this creative feeling. And sometimes I felt that in teaching I even had to cheat a little bit and make them believe that they could be open to this feeling. I always started the class with a simple band ring, because it taught them to cut out, measure, saw and solder. It required lots of very simple processes, and if you force a person to finish that ring really well, all of a sudden they see practically professional work in front of them. And even if you help them a lot, if you manage to make them believe it is their own effort, it is like you have opened a faucet. All of a sudden, the creativity begins to pour out.

In 1956, for the first time, I went to New York. I was already selling at Georg Jensen, but I wanted a one-man show. Conrad Brown, an editor at Craft Horizons, introduced me to store buyers and gallery owners. Finally I found a little jewelry office of conventional, not contemporary, things, called Walker and Eberling. This was the Walker whose brother founded Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The office was on the eleventh floor on East 59th Street, and they agreed to give me a show that autumn.

During my trip I saw an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art of Antonio Gaudi, the Spanish architect. Everything was sort of Art Nouveau and very, very baroque, very crazy. That show struck me with such force; I didn't realize it at the time, but my work started to change. I had also already realized that New York was the place I had to live. So I returned to San Francisco and told my mother that, even though we had built a lovely contemporary house on Russian Hill just two years previously, we had to move to New York. I just couldn't stay away. In two weeks' time I had found an apartment on West 55th Street in which we lived for 17 years. As soon as I started to work there people began to come to see my things. I remember how surprised I was when the first person picked up a ring and said, "But that makes me think of Gaudi architecture." It was a complete surprise to me, although I believe that what surrounds you, what strikes you, in your creative process, is absorbed and little by little is reflected in your work.

Another factor in my transformation to more organic work was the situation of my studio in our apartment. As we lived in a brownstone, I had no legal right to bring in, say, an oxygen tank, for soldering equipment, as I had had in my own house in San Francisco. There I had been working with oxygen and gas so I could do very fine soldering. So I had to revert to presto-light tanks, which were also illegal, but which I smuggled in. However, this equipment is not made for soldering, so I could not do such fine work. I started to cast pieces using the lost-wax process. This period when I did nearly exclusively wax casting was wonderful because it changed my outlook on the process. In Europe, people look upon casting as commercial. In America, it is considered a very creative process, and I learned lots of new, fantastic things because there is no limitation to what you can do with casting. I believe that wax work should never be done to resemble a constructed piece. You should use all the factors characteristic of the wax. Anyway, this contributed also to my changing style, because constructed work suggests a very stark style and wax work leads you into a much softer and looser form. I also believe that the fact that I lived in Manhattan, surrounded by all the stone and concrete, forced me to appreciate natural forms. At this time I did lots of close-up photography of vegetables and plants.

Soon after I moved to New York I started teaching one night a week at the art institute connected with the Museum of Modern Art and held in the basement of the museum. The school accepted both adults and children and they gave me a class of children. My teaching experience in San Francisco had been so rich that I always wanted to teach more. Seven years later the school was discontinued because the museum needed storage space. However, the nucleus of 10 people from my group continued meeting in my apartment. I had no place to work so they brought their pieces either finished or semi-finished. Each piece was passed around and criticized, both technically and design-wise, and then the work came to me and I summarized. Sometimes we complemented those sessions with slide shows. It was really a marvelous relationship, and now after some 30 years, every time I come to New York we have a reunion.

In about 1969 I discovered the Hanes water welder equipment for electronic soldering. With this system there is a tank of distilled water with electrolytic liquid which the electricity goes through and divides into oxygen-hydrogen gas. You guide this gas through a booster with methyl alcohol and borax to get a clean, fluxed flame, which is very hot—to 6000″ F. The flame can be so small you can barely see it or it can be rather large and long. When you solder a piece with ordinary equipment, you have to heat the whole piece to solder it together and you always use solder with it. With this soldering equipment you can spot weld. To make a good connection all you do is touch an area with the flame and it is welded. This both saves time and also gives a nice rolled edge, just like in the wax. Actually, because of this water welding method my work continues to resemble wax work. Just as the wax is liquid, so the metal becomes liquid with such a hot flame. This is exactly the same technique as used in steel welding. So I started using forging and welding, and the plant forms, the leaf forms, started to find a bigger and bigger place in my work. Maybe it's the time; maybe it's our age that does it. As I look at Merry Renk's work, I find her things have also become more organic, more plantlike.

In the 1970s I moved to Switzerland. Here I set up a studio but found that people were very conventional and reluctant to embrace modern work. I began to show my ikebana—Japanese flower arrangements—at a large ceramic museum, Musée du Petit Palais, in Geneva. After this show, the director offered me more space to include my gold jewelry with a large ikebana display. A curator of the Geneva City jewelry museum, Musée de I'Horlogerie de la Ville de Genève, also invited me to show my work. I prepared for two years for what became a 30-year retrospective of 135 pieces. Seventy-nine pieces from this show went to an exhibit in 1979-80 at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

When the price of gold went up in 1980, lots of people were reluctant to acquire gold jewelry. They wanted something less precious which they would feel free to wear. So I started to use silver as the base of a piece and to decorate it with gold. Using silver was somewhat ironic to me because in the very beginning I worked in silver and pieces sold for $12 or $14. That's how we all started. Now the value of the creative work is much more important than the material cost. In my current work I also play a lot with colors of metals. I take sterling which I oxidize black, and fine silver, which I leave white, and gold, which makes a very beautiful combination. Adding the colors of the stones enriches it more. I use lots of pearls which blend nearly entirely with fine silver and sometimes reflect a little of the gold color.

As to the future—I live my life as I read a book, page by page, and fortunately, sometimes the pages turn so fast I have a feeling I don't have time enough to read it thoroughly. I planned to go for a year to work in Paris on sculpture. I had been doing some medium-sized sculpture and lots of forged pewter, which gives an entirely new style to the work. I would still like to make bigger work. However, in 1982 I was asked to show my jewelry in a number of places in Switzerland, including Atrium Gallery in Basel and Florissan Gallery in Lausanne, and in a show in Yugoslavia, so I have been concentrating on making new jewelry pieces. Also, this year I completed my most important ecclesiastic commission of a tabernacle for a Greek orthodox church near Geneva.

But New York continues to attract me—the hustling, bustling life. New York is the only place where I can honestly say I can feel at home. I go away for two years and when I come back I go on the street and I have the feeling that I never left. I hope to return to New York to set up my studio and live in 1984.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Virtuoso Symposium Exhibition

TeNo: Emotion Meets Coolness

Observations: David Clifford

Bill Ruth and Susan Mahlstedt

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.