Master Metalsmith John Prip

8 Minute Read

One observation on the career of John Prip (more often called Jack) is the way in which the man and his times have grown together. In some people this might be a coincidence; in others it would indicate an ability to perceive and adapt to a trend. In Prip's case, though, it attests to the role he has played in setting the direction of American metalsmithing over the last 30 years.

When Jack Prip came to a fledgling institution called the School for American Craftsmen in 1948, its metals department was a workspace and an idea. When he left that school in 1954, it had become a department of Rochester Institute of Technology and was on its way to becoming one of the most prominent and respected departments in the country. When Prip went into industry in 1957 he carved out a niche for himself and the generation of designers that followed. When Prip went to the Rhode Island School of Design in 1963, he was given a room in the basement and a handful of students. When he retired from full-time teaching in 1981, he left a department that ranks among the best in the country. It's an impressive record.

As a teacher and an artist, Jack Prip has retained the spontaneous wonder that most of us leave behind in childhood. This quality, linked with inexhaustible drive, technical expertise and a quick compassionate humor, are brought together in the life of this man.

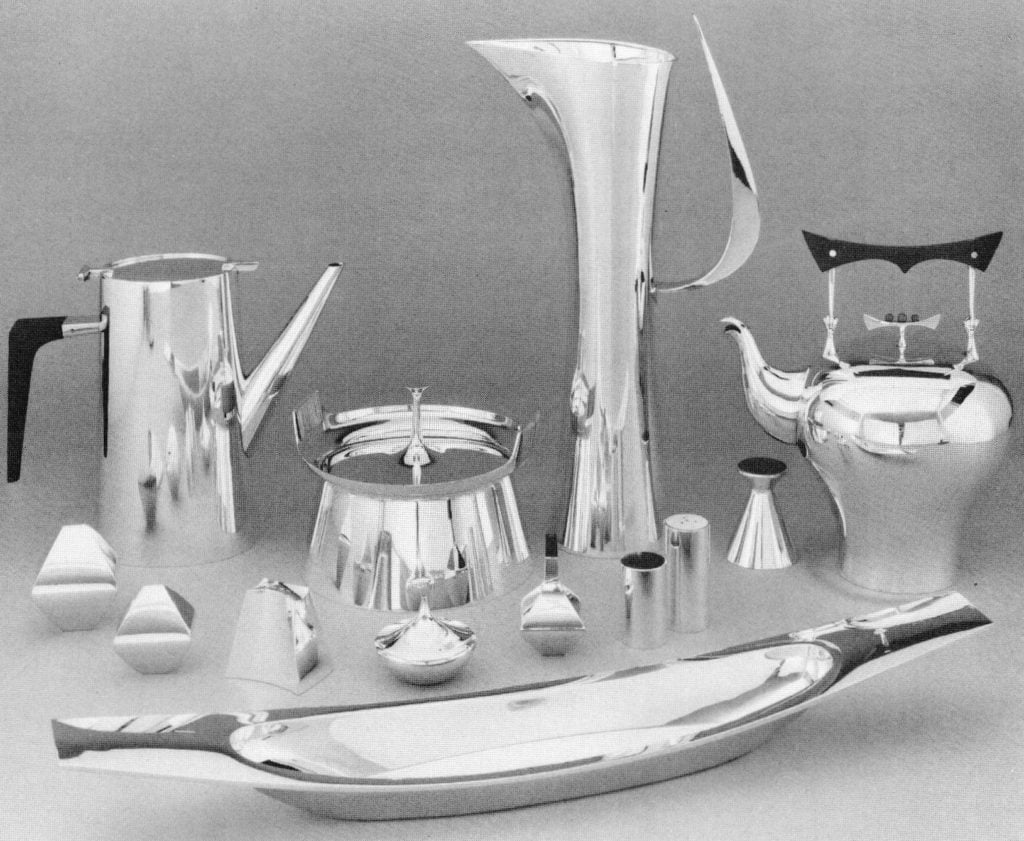

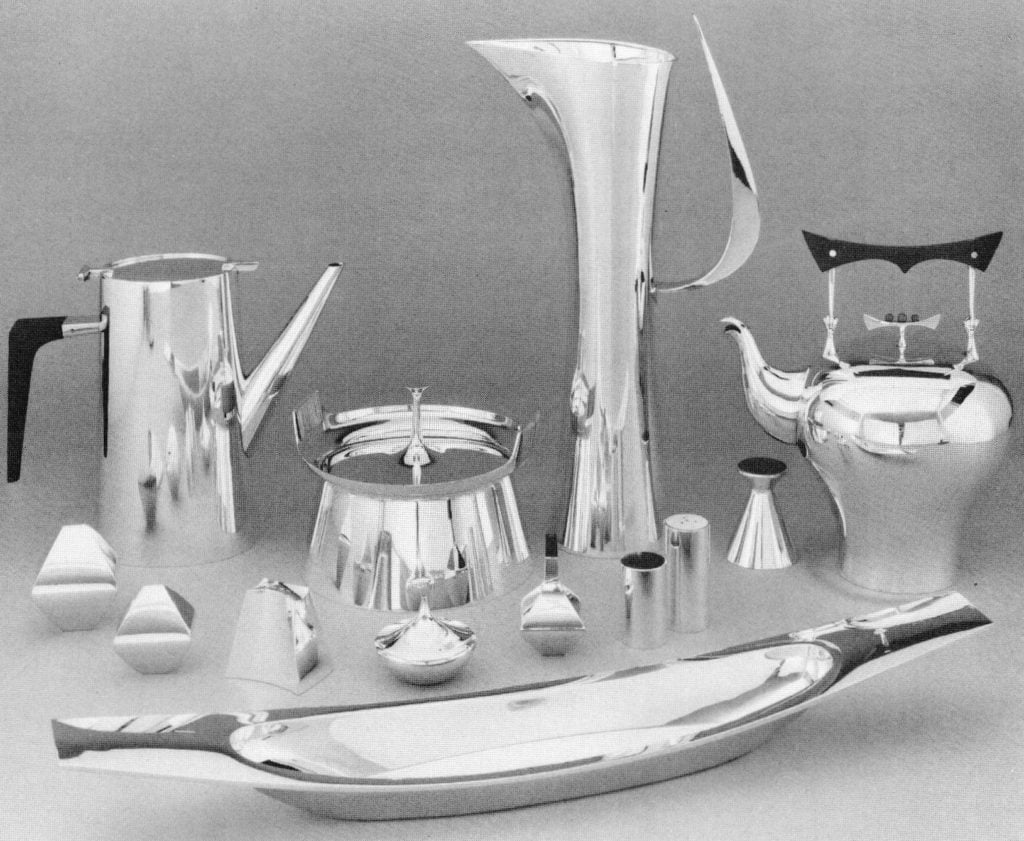

Holloware, sterling, made for Reed and Barton, 1957-59

At 15, Prip began an apprenticeship while attending high school. The next five years were spent polishing stakes, sweeping up and laboriously reproducing classical renderings. The experience taught diligence and a deeply rooted technical skill, but simultaneously imposed a restricted aesthetic. In a way it was the unlearning of these traditional forms and procedures that pushed the young silversmith into bold experiments and motivated the innovations that distinguish his career.

In 1948 Prip left postwar Europe with his wife, Karen, and infant son, Peter. He came over on the same boat with a woodworker named Tage Frid, who was to become a lifelong colleague and friend. They had both been invited to teach at a new school in Alfred, New York, called the School for American Craftsmen. At this time there was virtually no academic training for metalsmiths in the U.S. The School for American Craftsmen was one of the first such schools with a department devoted to metals. This opportunity allowed Prip to transplant his technical background into a fertile, unrestricted culture. The coming together of old and new worlds was an important and challenging time for him. In bringing the formal, technical tradition of Denmark into harmony with the American desire for innovation, the young silversmith was dealing not only with objects, but with basic questions of the relationships between makers, buyers and teachers. It became necessary to question every notion, every aspect of every design. The obsession with peeling away layers of "established" thinking has never ended.

When the school moved to New York, to the Rochester Institute of Technology, two years later, Jack and his family, which now included daughter, Janet, moved along with it. It was during this time in the early 50s that Prip and the craft movement were eagerly searching for their own style. The European tradition had proved to be a fitting point of departure for both the man and the movement, but an impatient energy was looking for new expression.

Small Teapot, sterling with ivory finial and reed wrapped handle, 1948

One of the needs of these early years-an economic as well as an artistic need-was for a marketplace. Along with Frans Wildenhain, Tage Frid, Ronald Pearson and others, Prip established a gallery in Rochester, New York, called Shop One. This gallery was a unique institution in its time, providing not only a business venture originated and managed by craftsmen, but also a forum for the presentation of top quality avant-garde craftwork. What distinguished Shop One from its successors was its sense of purpose. There was, beyond the hope for a viable income, a feeling of mission; a desire to educate the public to the special beauty of handmade objects.

Looking back on it this move into the marketplace was predictable. A central aspect of Prip's personality is a precocious curiosity, what a former student called a "questioning intelligence." He had come from Denmark directly into the American cubbyhole marked Ivory Tower. After six years of teaching he was uncomfortable with the irony of training students to pursue a livelihood as metalsmiths without having tried it himself. This kind of straightforward logic is typical Prip. Also, he needed to lay his ideas before a larger audience than the classroom provided. It was not of primary importance that the work be appreciated by the public; he had never intended to mold his style so as to cater to popular taste. But through Shop One and, in fact, throughout his life, he has sought a sounding board, a questioning intelligence of his own stature to propel him to new extremes.

In 1957, after three years with Shop One, Prip again felt the need to move on. Through some fortunate connections (and what I imagine was a persuasive charm, though Prip demures), he was hired by Reed and Barton Company, a holloware and flatware manufacturer in Massachusetts. The title invented for the role he conceived was Craftsman-in-Residence. He was given workspace, materials and access to the 900-worker factory. It was understood that Prip had a responsibility to address himself to work that might eventually profit the company, but beyond that guideline no restrictions were imposed.

Prip was to stay at Reed and Barton full-time for three years. During that time he made drawings, models and prototypes. One indication of his success there is the fact that 20 years later several of his designs are still in production. The relationship was one of those that benefited all involved, affirming the symbiotic possibilities between the worlds of craft and industry.

Bird Pitcher, sterling, 1950. Photo: Toza Radakovich

By this phase of his career, Prip had established a technical virtuosity that enabled him to pursue design innovations of impressive breadth and scale. From sculpture to jewelry, raising to electroforming, the "questioning intelligence" was on the prowl. Goading himself as he did his students, Prip committed himself to the job of reseeing the world around him. "I've always been interested in process; in the result of a process." This investigation into processes, both organic and technical, was to provide source material for many years of work.

Flatware, sterling, 1948-49. Later reworked for Reed and Barton in 1958 (Lark pattern)

Like most exceptional teachers, Prip is a shrewd observer of human nature. Though he would go for weeks without saying more than hello to a particular student, he was always evaluating. One incident typified his attention: Prip watched a student wrestling with a design dilemma but chose not to get involved until the student had truly exhausted her resources, having pushed-herself further than she at first thought she could have. When she was really going down for the third time, Prip, in a few sentences, made a connection between the problem at hand and a new medium. The student saw no relevance but sullenly pursued the suggestion. A couple weeks later the dilemma had evaporated and the ideas were flowing again. Now, 10 years later, the student still marvels over the incident. "I didn't think he even knew I was in the studio, but all the time he was watching out for me, playing out line and helping me along."

| Brooch, silver gold plated with mother of pearl, 1967 | Box, sterling electroformed gold finish and fabricated rhodium finish 6 x 4 7/8, 1971 | Gilley's Gull, Sterling 5 x 2 7/8, 1971 |

"Playing" is an appropriate word for Professor Prip. One of his favorite devices was to sneak back into the studio after everyone had gone home and rearrange the work laid out on people's benches. The students would return to find their containers turned into spouts, their jewelry stacked up like sculpture. It is easy to picture him delighting in his serious task, a kind of helpful elf gong awry. Just like the young silversmith 30 years before in Alfred, New York, Prip was still unlearning, still waging battle with the idea of convention. And as his battle has raged, he's swept many thankful students along with him.

Tim McCreight is an instructor at the Worcester Craft Center and a practicing metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Laser Welding Channel Repair

Jewelry Designs: Hope Pendant

Tips for Recovering Precious Metal Particles

Platinum Consideration Factors

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.